African American women and their babies are dying at alarming rates. According to the most recent data, black mothers are three to four times more likely to die in childbirth than their white, non-Hispanic counterparts, while the death rate for infants born to black mothers is more than twice that of infants born to white, non-Hispanic infants.1

A growing body of research suggests that even when clinicians control for education, income, and health, black women and their infants are dying at significantly higher rates than other groups of U.S mothers and babies. And while race is a consistent factor threaded throughout the data, the driver of these disparities is racism.

Racism, an evergreen toxin in American society, has long served as the primary ingredient of racial inequality. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Kerner Commission, a bipartisan group created by former President Lyndon B. Johnson to investigate the country’s seemingly endless civil unrest. The commission’s final report identified “white racism” as the main source of unrest in communities across the country.2 The commission stated, in no uncertain terms, that “our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”3

Fifty years later, the United States has yet to sufficiently take on the toxin of racism. Current data reveal that it not only continues to divide communities and promote unrest, but the daily exposure to racism is literally killing black women and infants.

This brief summarizes the growing body of research on racial disparities in maternal and infant mortality and concludes that racism is a key contributing variable. To combat this growing threat to black mothers and their babies, targeted policy responses must be deployed.

What’s known about U.S. maternal and infant mortality rates

Among developed nations, the United States has the worst rates of maternal and infant mortality (MMR and IMR, respectively). Disaggregated data show that wide racial disparities drive the United States’ abysmal record in birth outcomes. Based on data compiled from 2011 through 2013, for every 100,000 live births in America, 43.5 black mothers die. By comparison, 12.7 non-Hispanic white mothers die for every 100,00 live births.4 Further, for every 100,000 live births in America, 11.7 infants born to black mothers die, compared with 4.8 infants born to non-Hispanic white mothers.5

Researchers are examining the different aspects of daily life that could contribute to such high rates of death among black mothers and their infants. They are looking at a range of protective factors that positively affect maternal and infant mortality rates such as higher levels of education, income, and access to quality health care. A recent report, produced by Duke University’s Samuel Dubois Cook Center on Social Equity and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development, found that “many of the protective factors that reduce IMR in the general population have little or no significant influence on IMR for black women.”6

Protective factors

Various studies have shown that the following protective factors may curb maternal and infant mortality rates for many women—but not necessarily for black women.

Education

Racial disparities in educational outcomes have shrunk significantly over the past 50 years. Today, African Americans are twice as likely to have a college degree than in 1968. More specifically, in 1968, just 5 percent of black women were college graduates. Today, 1 in 4 black women are college graduates.7

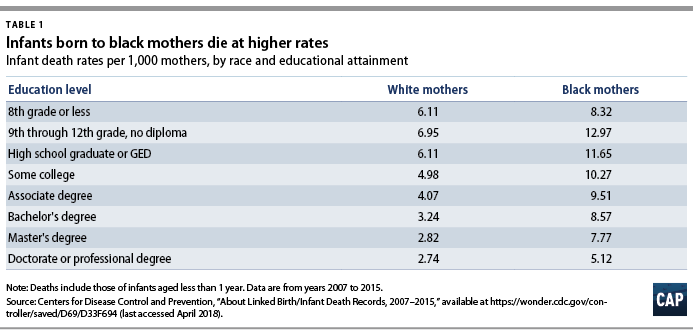

Policymakers have long thought of education as the silver bullet in reducing poverty, improving health, and enhancing overall quality of life. Yet, the research isn’t necessarily bearing these assumptions out. While educational attainment does increase income levels for black people, increased incomes alone don’t guarantee better health outcomes, especially for black mothers and their children. According to the American Journal of Public Health, achieving postsecondary education improves birth outcomes for white women but not African American women.8 In addition, the study found that at every maternal educational level, infants born to African American mothers had a higher risk of dying than those born to white mothers.9 Ironically, postsecondary education reduced the risk of death among infants born to white mothers by 20 percent but had zero impact on those born to African American mothers.10 More starkly, a study conducted by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene found that black non-Latina women with at least one college degree have higher severe maternal morbidity rates than all other women who never graduated high school.11 These sobering findings suggest that for black women, obtaining higher education doesn’t necessarily offer protection from or minimize the likelihood of mortality.

Income

Since 1968, black people have increased their overall income. Yet, black workers today still earn just 82.5 cents for every dollar earned by a white male worker.12 For black women, specifically, they face a 63 percent wage gap compared to white men.13 In 1968, black families had a median wealth of $2,467 that has since grown more than five times that amount to $17,409 in wealth today. And although median white household wealth grew at a less rapid pace—slightly more than tripling in the past 50 years—the median wealth of a white family today stands at $171,000 further entrenching the racial wealth gap.14

Data show that while increased income improved birth outcomes for white women, black women do not experience these same effects. For example, for white women who experienced childhood poverty, increased adult family income is associated with a 50 percent decrease in having a low birth weight child. But for black women who grew up in poverty, the increase in family income in adulthood had such a small impact on infant birth weights that it fails to provide statistical significance.15 Moreover, black women are three times more likely to have a life-threatening complication during delivery than white women, regardless of income or education levels. In addition, black non-Latina women living in low poverty neighborhoods had a higher rate of severe maternal morbidity than all other racial groups who live in “very high” poverty neighborhoods.16 Ultimately, a higher economic status for black women does not mitigate the risk for maternal and infant mortality.

Health care

Policymakers often raise overall quality of health and lifestyle choices as possible indicators for risk of maternal and infant mortality. The quality of one’s diet, smoking, and overall health are indicators for birth outcomes, but studies reveal that such factors may not affect racial disparities.17 For example, even when comparing non-obese African American women to obese white women, obese white women have better outcomes in both infant and maternal mortality.18 Similarly, it is a known fact that access to quality and affordable health care is critical to reducing maternal and infant mortality rates. And while the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) increased the number of African Americans accessing coverage, African American women still access prenatal care at lower rates than their white counterparts. Furthermore, even for those African American women who access prenatal care in the first trimester, they still have higher rates of infant mortality than non-Hispanic white women with late or no prenatal care.19

The persistence of racism

Racism is the one constant toxin contributing to the maternal and infant mortality rates of black women. According to the iconic anthropologist Ruth Benedict, in her 1945 seminal work Race: Science and Politics, she describes racism as “the dogma that one ethnic group is condemned by nature to hereditary inferiority and another group is condemned by nature to hereditary superiority.”20 Centuries of subjugation, by individuals and systems have created a toxic environment for African Americans, especially African American women.

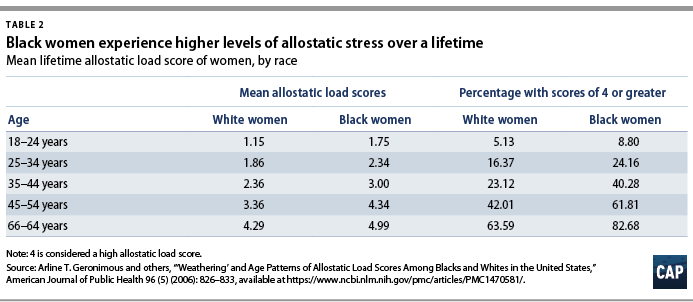

The “weathering hypothesis,” introduced in the early 1990s by Arline Geronimus, examines the idea that anticipating and managing racism increases stress levels for black people. For black women, this clearly manifests itself in maternal and infant mortality rates. One study, published in the American Journal of Public Health, measured the levels of physiological effects of stress, or the “allostatic load,” and found that black women consistently report higher levels of stress.21 Specifically, black women are twice as likely to have high stress scores as white women—regardless of age. The impact of systematic racism is manifesting itself in black women’s health.

In addition, research reveals that discrimination produces negative results on one’s overall health indicators. According to Michael Lu and Neal Halfan, authors of Race and Ethnic Disparities in Birth Outcomes: A Life-Course Perspective, the constant wear and tear of racism on black women’s bodies can manifest later in life, compounding with stress to negatively affect maternal and infant health outcomes.22 This theory is further supported by the work of Lisa Rosenthal and Marci Lobel, who looked at the historical and social effects of gendered racism. They found that social conditions including exposure to offensive stereotypes about black mothers, such as irresponsible mothers or hypersexual, coupled with the sordid history of abuse by the medical field on the black community also contribute to the toxic stress levels of black women.23

To help make the point, consider that while access to health care has significantly improved since the passage of the ACA, the quality of care could be further refined. Data reveal that black women are nearly four times more likely than white women to report worse experiences than other races when seeking health care. For example, National Public Radio and ProPublica in collecting more than 200 stories of black mothers about their health care interactions, found a constant theme of “being devalued and disrespected by medical providers.”24 This reality was further amplified by tennis professional Serena Williams. In relaying her own harrowing childbirth experience, Williams stated, “doctors aren’t listening to us, just to be quite frank. I was in a really fortunate situation where I know my body well, and I am who I am, and I told the doctor: ‘I don’t feel right, something’s wrong.’” Without proper treatment, Williams could’ve died from complications following the birth of her daughter.25

In their day to day lives, black women are five times more likely than white women to report experiencing a headache, upset stomach, tensing of muscles, or a pounding heart because of how they were treated in society based on their race in the past month. Black women are also five times more likely to report emotional distress because of how they were treated based on their race in the past month. In fact, more than 1 in 7 black women report experiencing emotional distress due to how they were treated based on their race in the past month.26 Furthering this point, Linda Goler Blount, president and CEO of the Black Womens’ Health Imperative shares, “it’s not race so much as racism and the experience of being a black woman or a person of color in this society” driving this disparity.27

In addition, Keisha Bentley-Edwards, co-author of “Fighting at Birth: Eradicating the Black-White Infant Mortality Gap,” states that “particularly for black women, despite age, educational attainment and socioeconomic status, the exposure to racial inequities and injustices throughout their life directly impact their birth outcome.” 28 She goes on to say that understanding the research requires a rejection of the tendency to point to traditional risk factors such as obesity or alcohol consumption. Instead, it is “crucial to recognize that greater vulnerability of black infants cannot be explained by these factors.”29

Conclusion

America was founded on idealistic and visionary principals that have sadly yet to be fully realized because of deep-rooted and persistent racism. Today, the United States is the richest nation in the world, yet black women and their infants are dying at higher rates than women in other developed countries.30 Research and data continue to show that racism is the evergreen toxin permeating all aspects of American society—and it is killing black women and their babies. To combat systemic racism, the United States must employ systematic policy changes.

To that end, the theory of “targeted universalism,” an equity framework that focuses on executing targeted strategies to meet universal goals, is the way forward. Targeted universalism provides benefits to “both the dominant and the marginal groups but pays particular attention to the situation of the marginal group.”31 History, research, and data prove that racism must be addressed directly. As Anne Price, president of the Insight Center for Community Economic Development, stated, “to address the root cause of the black IMR and the systemic racial inequities that impact black families, we must execute policies that support equal opportunity and serve to support mothers, especially black mothers.”32

If the universal goal is to close the maternal and infant mortality gap—which it unquestionably should be—policies and programs that are targeted to black mothers must be implemented. A failure to target resources to those most in need will only further entrench the problem.

Methodology

To measure African American women’s experiences with racism, the author utilized the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Established in 1984, BRFSS collects data about health-related risk behaviors, chronic health conditions, and use of preventative services among U.S. residents. BRFSS is the largest continuously conducted health survey system in the world and conducts more than 400,000 interviews with adults each year. For this report, the author constrained the sample to U.S. residents who answered questions within the BRFSS Reactions to Race (RTR) module between 2012 and 2015 (N=53,279). The author then analyzed data within this module to study the relationship between an individual’s race and likelihood of experiencing an adverse experience because of their race. The author’s findings are based on summary statistics from the RTR module and the relationships between race and adverse experiences were confirmed by running several different linear probability regression models with adverse racial experiences as the dependent variables and education, income, age, and state as covariates.

Data limitations may have some effect on the overall results. For example, the CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System only contains data from six states—Arizona, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Mexico, and Wyoming. These states are geographically and demographically diverse and produce a sample size of 53, 279. Still, readers should use caution when drawing national conclusions due to the possibility that including additional states would have a statistically significant effect on the RTR data. Another limitation of this study is that the BRFSS RTR data is limited to 2012 to 2015. While these years still produce a large sample for analysis, this report would benefit from additional survey years.

Danyelle Solomon is the senior director of Progress 2050 at the Center for American Progress.