The federal and state laws and associated regulations that guide how educators teach students with disabilities, ranging from mild learning disabilities to significant cognitive or physical impairments, grew out of the civil rights movement. While students with disabilities had historically been largely segregated from their peers and provided with little if any educational opportunities, the equal protection clause of Brown v. Board of Education provided the foundation for key federal laws that frame special education practice in U.S. public schools today: Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the Education of all Handicapped Children Act of 1975—which evolved into IDEA—and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.14

Students identified as having one of 13 disabilities are eligible for special education and related services identified under the federal IDEA.15 Public schools are required to provide students with disabilities with a free appropriate public education, or FAPE, in the least restrictive environment, or LRE, appropriate for their needs and to provide parents with explicit rights to ensure that states and districts comply with the statute.16 In practice, students eligible for special education are provided accommodations and modifications that enable them to access the general education curriculum and make academic progress.17 While the special education and related services that students with disabilities receive under IDEA are a key component of improving outcomes for these students, these individualized services are still only a part of what must be a broader approach to serving students with disabilities—and all students. Students with disabilities need high-quality, effective instruction in inclusive settings, and they should have access to differentiated services and supports as soon as a need is identified.

Shoring up high-quality instruction for all kids, including students with disabilities, is critical, as 95 percent of the students eligible to receive special education are enrolled in traditional district schools and spend significant time in the general education classroom. While there is significant variation between states, on average, 63 percent of school-age students with disabilities spend 80 percent or more of their day in the general education classroom, and another 19 percent spend at least 40 percent of their school day in the general education classroom.18

Providing highly individualized supports to students in compliance with federal and state regulations is one of the most complex areas of education. Special education policies and structures—designed to enable students with disabilities to access the general education curriculum alongside their peers—vary across states and districts; are regulated by federal and state laws; and are supported by federal, state, and local revenues. In addition, as described above, students with disabilities are supported and protected by various laws and programs, which, unfortunately, are not always easily aligned. For example, while a student with disabilities is afforded all of the protections under IDEA, schools must also afford them the supports and opportunities required by the Every Student Succeeds Act. The body of laws and related regulations are nuanced and can be daunting to new charter school operators, many of whom may have limited experience navigating the complex web of administrative requirements that shape so much of special education in public schools.19

Special education challenges

Twenty-five years into the charter sector, there is ample documentation that charter schools have struggled, to varying degrees, to ensure equitable access for students with a diverse range of disabilities and to amass and sustain the capacity to provide high-quality services.20 The factors contributing to the challenge are myriad and have even included reports of some charters discouraging students with disabilities from enrolling.21 First, while funding is a perennial challenge for all public schools, charter schools’ small size, prohibition from raising revenues through taxes that are potentially available to traditional districts, and general inability to realize economies of scale critical to providing a full continuum of special education services is problematic.22 Second, charter authorizers have historically not devoted adequate attention to clearly articulating roles and responsibilities associated with educating students with disabilities or developing metrics to track their success.23 Finally, states, districts, and charter authorizers have struggled to retrofit regulatory structures developed before charter schools were created and in states where charter schools operate as part of a local district, in order to operationalize how they share responsibility for provision of special education within these structures.24

Due process and legal actions

Parents’ ability to file a grievance when they are concerned that a school is not fulfilling its obligations to provide FAPE is a key avenue to protecting their children’s rights. During the 2012-13 school year, parents or advocates submitted 16,980 due process complaints related to compliance with IDEA. The majority of these complaints—11,164 representing 65.8 percent—were resolved without a hearing. Yet the complaints provide insight into how often parents and schools—traditional districts and charters alike—clash regarding special education.25 Charter schools have been the focus of due process complaints as well as complaints submitted to the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, or OCR, and the Department of Justice’s Office for Civil Rights. While there is no national repository for individual parent due process complaints, public reporting of complaints submitted to the respective offices for civil rights provide insight into how some of the challenges are translating to formal grievances and the collective understanding of how relevant laws are being applied to autonomous charter schools. Since October 2013, the Department of Education’s OCR has issued 71 letters stemming from complaints against charter schools.

Examples of OCR complaints related to educating students with disabilities in charter schools

- In 2014, the OCR investigated a complaint filed against a CMO in Texas alleging significant underrepresentation of students with disabilities—2.7 percent in the CMO compared with 7.3 percent in the local districts—and English language learners—11.5 percent compared with 22.5 percent—stemming from discriminatory enrollment and discipline practices.26 The complaint was resolved with a resolution agreement outlining specific steps, such as adding nondiscrimination statements regarding students with disabilities on recruitment materials, the CMO was required to take to ensure compliance with relevant federal and state statutes.27

- In 2014, parents filed a complaint against a charter school in North Carolina alleging violation of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 stemming from the school’s refusal to provide services to a student after an evaluator determined that the student qualified to receive them. After determining that the school had violated Section 504 by failing to have appropriate policies and procedures in place to serve qualified students, the OCR developed a resolution agreement that required the school to fulfill specific actions to demonstrate compliance with the law.28

- In 2014, a complaint was filed with the OCR alleging violation of Title II of Section 504 regarding access to facilities, programs, services, and activities for English language learners and students with disabilities in charter schools in Wisconsin. As the authorizer, the school district was the defendant in the complaint. The district entered into a resolution agreement with OCR that involved the district ensuring that these subgroups of students would have equal access to the charters. The schools would also provide parents with information about how to access the schools and ensure that the schools were physically accessible to students with disabilities.29

- In 2016, a cohort of parents filed a complaint with the OCR against a CMO in New York that alleged discrimination against students with disabilities stemming from the failure to identify students as eligible for special education or to provide accommodations; illegal discipline practices; and inadequate communication with parents regarding their rights associated with accessing special education and related services.30 The complaint has yet to be resolved.

Special Education in the Charter Sector

In June 2012, the federal Government Accountability Office, or GAO, released a nationwide analysis of enrollment data; the report was spurred by public concerns that charter schools were not serving their fair share of students with special needs as required by law. The GAO reported that in 2008-09, the share of students with disabilities enrolled in charter schools was 7.7 percent, compared with traditional public schools at 11.3 percent. In the 2009-10 school year, the GAO found that 8.2 percent of all students enrolled at charter schools were students with disabilities, compared with 11.2 percent observed in traditional public schools.31 As result of these findings, the GAO urged charter schools to examine how their practices affected special education enrollment and recommended that the department conduct deeper research on the factors that influence enrollment.32 In November 2015, the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools, or NCSECS, released a comprehensive report using the 2011-12 Civil Rights Data Collection, or CRDC, maintained by the department and found that, nationally, students with special needs made up 10.4 percent of total enrollment in charter schools compared with 12.55 percent of all students in traditional public schools—a 2.15 percent gap.33 Based on the GAO data and that reported by the NCSECS, the enrollment difference between the two types of schools has been dropping over time: from 3.6 percent to 3 percent to, most recently, 2.15 percent. Analysis of the recently released 2013-14 CRDC will provide additional insight regarding this apparent recent trend.

Concerns regarding special education in the charter sector

Currently, 43 states and the District of Columbia have charter school laws, and there are approximately 6,800 charter schools operating across the country that serve an estimated 2.9 million students.34 While the charter school model has undoubtedly captured the imagination of policymakers, parents, and school leaders, the schools and policies have also generated criticism and critiques. Since the inception of the charter sector in 1991, critics and scholars have questioned the extent to which charter schools welcome and provide adequate services to students with disabilities.35 Research has documented that while many charter schools have struggled to amass the requisite expertise to effectively service students with disabilities, there are ample examples of charter schools creating successful special education programs. For instance, CHIME Institute in California has developed a national reputation for creating a dynamic and wholly inclusive environment for students with significant disabilities.36 Another example comes from Massachusetts’ UP Education Network and its methodical approach to moving students from self-contained to inclusive classrooms as part of its focused school turnaround work, which has demonstrated notable improvements in outcomes for students with disabilities.37

Concerns regarding special education in the charter sector range from broad questions about schools generally limiting access to narrower concerns about access for students with more significant disabilities. Other common areas of concern include the quality of programs for students with special needs and practices, such as discipline, that might have a disproportionate impact on students with disabilities. The growth of specialized charter schools designed primarily to serve students with disabilities also raises questions about inappropriate segregation of students with disabilities.38 While these specialized charter schools appear to be filling a parent-driven demand, advocacy groups that have fought to have traditional districts move away from segregated settings have expressed concerns that specialized charter schools may lead to students being counseled into settings that are not the least restrictive environment or that may not be accessible to all students with disabilities. In particular, advocacy groups are worried that specialized charter schools are more common for a narrow subgroup of special education students, such as students with autism or learning disabilities.39

While autonomous charter schools have unique opportunities to innovate, they can struggle to leverage the opportunity for students with disabilities given practical financial and staffing limitations.40 However, collaborating with districts has the potential to optimize both district systems and expertise and charter autonomy to improve the quality of education for students with disabilities in both. In particular, new charter schools, small charter schools, and—more importantly—the students with disabilities who elect to enroll in them stand to benefit from collaborative relationships with school districts that have established special education expertise. Those districts that function as authorizers may be uniquely positioned to encourage collaboration by virtue of an explicit shared interest and the valued district resources that they can make available to their authorized charter schools.

The collaboration in Denver, described in detail below, is tightly connected to the allocation of facilities and capital improvement expenses. Charter schools need access to facilities and construction funds to appropriately serve students with significant disabilities. Denver Public Schools, as the district, controls access to excess facilities, and state facilities bind funding and can allocate them to charters, which agree to house center programs. Not all district authorizers are as sophisticated as Denver in their portfolio management of schools; however, Denver’s management highlights the opportunity for high-quality district authorizers to leverage resources as an incentive for charter collaboration.

Districts that do not serve as authorizers may also see the benefits of collaborating with charter schools, and the relationship would be arguably simpler absent the oversight role that is central to authorizers. However, these collaborations would most likely require some explicit incentive or apparent mutual interest in order to occur given historical tensions between the two entities.

While many charter schools have created special education programs that enable students with disabilities to succeed, many more students would benefit from support and access to technical expertise to improve programs for students with disabilities.41 Collaborating with districts that have additional scale and established expertise builds opportunities to:

- Collaborate to better serve students with disabilities in charters

- Ensure access to innovative schools for students with disabilities

- Create cost-effective solutions for districts and charters

District-Charter Collaboration on Special Education: Denver Public Schools

Background

Denver Public Schools wanted to increase the number of students with significant disabilities who are educated in district-authorized public charter schools. Using facilities allocation authority, capital dollars for retrofitting space, and a collaborative decision-making process, DPS has begun placing specialized center programs for students with severe to profound disabilities in charter schools. DPS will continue to expand the number of such programs until charters reach parity with traditional district schools in terms of the proportion of students with significant disabilities served.

DPS serves more than 91,000 students, including 17,000 attending charter schools under district authorization. Both sectors serve a student population in which approximately 9 percent have mild to moderate disabilities, and these students are served in inclusive classrooms alongside their peers. Approximately 1.5 percent of DPS students have severe to profound disabilities, and based on the level of specialized services they require, they are placed in center programs within schools distributed across the district. While less restrictive settings are always the goal, for some students, their individualized education plan, or IEP, teams have determined that a separate center program setting outside of the regular classroom is the least restrictive environment appropriate. These decisions are made on an individual basis. In the 2015-16 school year, charter schools had increased the number of students enrolled with more significant disabilities, but these students still made up just more than 0.5 percent of their student population. DPS was concerned that the lack of specialized programs in charter schools was limiting access for students with more significant disabilities.42

As part of Denver’s well-known school choice process, parents of students with disabilities are sent official notification of the school to which their child is assigned based on the needs and services documented within their child’s IEP. Notification is sent prior to the start of the choice process for a given school year and includes a list of other schools, both district and charter, which offer similar services to the assigned school. This is similar to the process for all other students in the district, in which they are assigned to their neighborhood school and then have the option to enter the choice process to enroll in other district or charter schools.43 While parents may select a school of their preference, not all schools have center-based programs; not all centers have excess space available; and the district does not provide transportation for schools of choice. Providing additional center programs in charter schools is an effort to address both choice gaps and geographic needs for the district.

In 2010, the district and its charter schools signed a Gates Foundation District-Charter Collaboration Compact, securing $4 million to facilitate collaborative work between the two sectors.44 Among other commitments, the compact specifically called out access to district facilities for charter schools and a need for charter schools to equitably serve all students with disabilities. This compact provided a common set of expectations and an opening for conversations about collaboration with DPS-authorized charter schools. Collaboration in Denver has taken many forms, but the two special education collaborations have focused on improving compliance and support services to charter schools and placement of center programs in charter schools.

Collaborating to better serve students

Historically, DPS only notified district or charter schools about the planned opening of additional center programs each May, when the center program would need to open in August of the same year. Some charter schools, including STRIVE Preparatory Schools successfully pushed for changes to this short timeline that they felt was not good for teachers or students. Kaci Coats, the senior director of student services for STRIVE Prep, shared in a phone interview, “The district was telling us to do something at a certain time without clear criteria for center placement and no clear channel for decision-making.” Coats called the process reactive and contrasted it with the more proactive planning of STRIVE Prep, noting, “We like to have our ducks in a row.” As a result of this request and following the example of how charter schools plan for opening their own schools, DPS now gives all schools—both charter schools and district-run schools—a planning year, or “Year 0,” to allow for adequate planning, training, and staffing of new center programs before they open.

Josh Drake, executive director for exceptional students for DPS, noted in a phone interview that facilitating sustainable collaboration is difficult, but his staff—and the charter schools they partner with—remain excited about hard work that leads to better outcomes for students. Clear communication and collaborative connections between staff have helped facilitate this work. For example, DPS has created a Center Program Plan that acts as a touchstone for schools to refer to and addresses the common questions that schools need to answer, as well as details that are helpful to planning for the operation of specific disability programs. Coats has also worked very closely with the DPS district support partner assigned to STRIVE Prep. This role used to simply ensure compliance with special education requirements and rarely reached out unless the school made a mistake. But according to Coats, she is now in daily communication with her DPS counterpart about questions and concerns from special education leads at each STRIVE campus and the larger collaborative initiatives. Coats said there is now “a trust that we are both coming at this from a place about what is right for and best by kids and families.”

Ensuring access for students with disabilities

In the spring of 2012, there were only two charter schools in Denver with center programs, serving approximately 10 students with severe and profound disabilities. This left a significant gap between district-run and charter schools with respect to providing a full continuum of service options for students with a diverse array of needs. While some geographic areas of the district required additional capacity for students with severe and profound disabilities, the traditional school buildings in those areas did not always have space. DPS used bond money to retrofit facilities and sought to meet two goals at once: providing facilities to charter schools and ensuring access to such schools for students with disabilities.45 This opportunity came at a time when the district special education team was considering how to reduce the number of students served in centers; how to best accommodate the geographic need for center program space; and how all of that work intersected with the expansion of school choice within the district.46

As of spring 2016, there were 16 center programs with 100 students in charter schools. At that time, DPS schools housed 109 programs serving 1,400 students. The district expects that there will be 40 center programs serving 350 students in charter schools by spring 2019. DPS is aiming to be the first school district to reach parity in its percentage of students with significant disabilities served in charter schools. DPS sees clear benefits to being able to maintain specialization via additional center programs sited in charter schools around the district. “We have a coherent whole,” Drake said of the structure. He added that charters can balance the capacity of the district to provide services and to minimize travel for kids.

As the collaboration on center programs grows, DPS is working on more transparent principles and criteria, including a formal process for identifying center program sites. The process must consider the needs of the student population, the geographic distribution of programs, and the siting of programs in schools that offer a high-quality education to all students—both general and special education.

District-Charter Collaboration on Special Education: Los Angeles Unified School District

Background

The Los Angeles Unified School District wanted to encourage authorized charter schools to return to the district’s special education local plan area, or SELPA, after a significant number of charter schools joined an all-charter SELPA organized by another county. The district created options for charter schools to be part of LAUSD’s SELPA that offered different levels of service provision, support, and autonomy. Nearly all of the charters have returned to the LAUSD SELPA, while also creating a number of specialized programs for students with disabilities.

In California, all traditional school districts and county offices of education are local educational agencies, or LEAs. These LEAs are also members of a special education local plan area, a regional consortia created in 1977 to provide a full continuum of special education services to meet the needs of all children residing in the geographic area. Charter schools in California may be part of the LEA which authorized them or may serve as their own LEA.47 If a charter is part of its authorizer’s LEA, it is automatically part of the LEA’s SELPA. If it elects to be its own LEA, it must apply for membership in a SELPA. There are 135 SELPAs in the state, but only 25 currently accept charter school members.

In 2007, charter schools were frustrated by the lack of SELPA membership options available to them, which limited the potential to act as independent LEAs for special education purposes. In response to this frustration from charter schools, the California State Board of Education requested recommendations for a regional approach to charter SELPAs.48 A task force drafted recommendations for charter schools to gain membership to SELPAs—including those not within their own geographic region.

In Los Angeles, charter schools were “looking for a more equitable funding and service delivery partnership, either within LAUSD or in another entity, statewide,” said Gina Plate, senior special education advisor at the Californian Charter Schools Association, in a phone interview. Each charter pays what LAUSD terms a “fair share” contribution, which is a share of the charter’s state public funding allocation to cover the cost of educating students with the most significant disabilities across the district.49 Kim Dammann, managing director of special education at KIPP LA,50 recalled in a phone interview that the difficulty of accessing supports and programs—despite paying fair share funding—was the impetus for charter schools to start exploring options. In school year 2011-12, 22 charter schools authorized by LAUSD, though not KIPP LA, left the LAUSD SELPA to join an all-charter SELPA formed by the El Dorado County Office of Education.

Losing such a large number of charter schools hurt the LAUSD SELPA. It resulted in a loss of funds to the SELPA itself, and LAUSD also lost control over the special education services provided to charter LEAs they authorized that were located in their geographic area. Consequently, LAUSD wanted to find a way to retain as many charter schools within their SELPA as possible and convince those that had left to return. This became the impetus for the reorganization of the LAUSD SELPA and the collaboration with Los Angeles charter schools. In January 2011, the LAUSD Board of Education voted unanimously to restructure the existing LAUSD SELPA to include the Charter Operated Program, or COP, with three options for membership. Since the creation of the options, nearly all of LAUSD’s authorized charters have returned to membership in the LAUSD SELPA.51

Creating cost-effective solutions

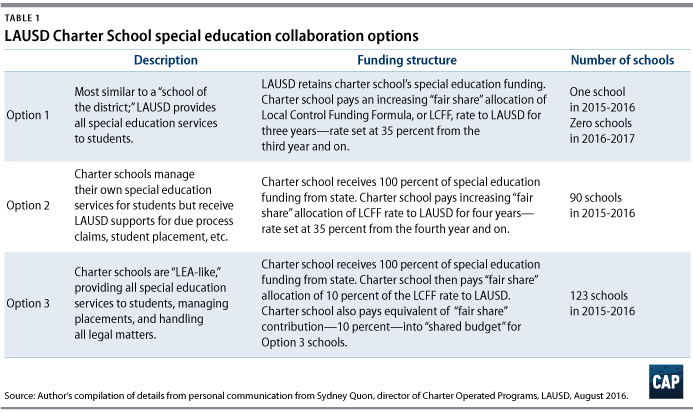

All charters authorized by the district may select one of three SELPA membership options. (see Table 1) While a “school of the district” option, Option 1 in LAUSD, is required in California statute, the small number of charter schools that have chosen Option 1 is a result of both an interest in greater autonomy by charters and a deliberate effort on the part of the district to encourage this autonomy.

More than 40 percent of charter schools select SELPA membership under Option 2, which provides some direct support from LAUSD. Option 3 offers the greatest autonomy for charter schools and is also the deepest level of collaboration with the district. All charter schools selecting Option 3 send representatives to a coordinating council that meets monthly for information sharing and professional development. In February 2012, Sydney Quon joined the staff of LAUSD as the director of charter operated programs. She is an employee of the school district, but Quon’s position is primarily funded by the Option 3 charter schools within the LAUSD SELPA.

Leaders from 39 charter school organizations elect nine voting members to serve on the executive council board, which approves the budget for spending the “shared budget” funds and determines the recipients of program grants given to charter schools. 52 Overall, 86 percent of the funds in the shared budget that charter schools pay into goes directly back to schools. Some of the funds are used for COP staff at the LAUSD SELPA; some funds support nonpublic school placements for students with severe needs; and other funds are used to provide grants that charters may use to start programs to serve students with more moderate to severe disabilities. Interviews highlighted that the membership of authorized charters in the LAUSD SELPA has allowed charters to build special education capacity while maintaining autonomy, to contribute financially to the collective work of serving students with disabilities in LAUSD, and to leverage the SELPA relationship with the district as a means of better serving students.

Collaborating to better serve students

In Los Angeles, KIPP LA’s experience highlights the potential for autonomy and collaboration under Option 3. The autonomy and freedom to innovate within Option 3 aligns with KIPP’s own value of “Power to Lead.”53 KIPP LA had previously been a SELPA member under Option 2, but struggled to support students with significant needs. Kim Dammann shared in a phone interview, “There was some truth to the district saying ‘you’re not serving these kids,’ because we were sending them back to the district for placement.” KIPP LA tried a pilot of Option 3 with one of its midsize campuses, motivated by the desire to try and create a program that could serve an enrolled very young student with an intellectual disability. Under Option 3, KIPP LA applied for a program grant. The grant provided KIPP LA with three years of funding, which decreased each year as the CMO worked to internalize the cost of the new programming. In partnership with LAUSD, KIPP LA staff observed schools with model programs and worked to build a program that included an itinerant provider who served students across KIPP campuses and whose excess time could be made available to other charters with similar student service needs. KIPP LA now operates seven specialized programs. Two of these programs are fully developed and have been replicated: a program for students with intellectual disabilities and a program to assist students with transitioning from district special day programs to an intensive inclusion setting with blended learning support. The CMO is also working with LAUSD to build a third distinct program, a therapeutic alternative to a nonpublic school serving elementary and middle school students with intensive socioemotional needs. KIPP LA shared that through this work they now have 75 staff focused on special education across their 13 schools and specialized programs. Each of the specialized programs now operated by KIPP LA was directly made possible by the seed funding from, partnership with, and expertise of the LAUSD team members.

Ensuring access for students with disabilities

Both Quon and Dammann highlighted in interviews the important successes of the options approach and the opportunities they create for collaboration that directly and tangibly benefits students with disabilities. A recent report from LAUSD’s Office of the Independent Monitor commended charter schools for continuing to increase the enrollment of students with disabilities. According to the report, general enrollment at charter schools increased 2 percent in the 2015-16 school year, but the enrollment of students with disabilities increased nearly 10 percent. The monitor noted that the “increase in [students with disabilities] enrollment is evidence that the changes to the policies and practices for servicing [students with disabilities] have resulted in a positive outcome.”54

Charter schools are noticing a variety of benefits from their partnerships with the district to improve students with disabilities’ access to high-quality services. Dammann said, “The communication is really the win. The resources are great, but the improved communication is key.” She credited the district with embracing this opportunity to work with charter schools and says, “Our relationship with LAUSD has really improved from where it used to be.” She also expressed pride at what charter school organizations such as KIPP LA have been able to accomplish through this collaboration with the district. Dammann shared: “We are owning that all of these kids [with disabilities] are our kids—mild, moderate, or severe—and we’re going to keep them all and serve them the best way we can.” LAUSD’s Quon praised Option 3 schools in her interview for using their autonomy to “think outside of the box and be more creative to move forward” the practices used to serve kids.

District-Charter Collaboration on Special Education: Central Falls, Rhode Island, and Blackstone Valley Prep Mayoral Academy

Background

As Blackstone Valley Prep Mayoral Academy, or BVP, grew, the organization’s leadership recognized a need to have dedicated administrative leadership for special education. As part of a wider collaboration effort, BVP developed a partnership with Central Falls School District to provide special education administration, professional development, and provision of some specialized services for BVP students. This partnership has enabled BVP to benefit from the deep expertise within CFSD in a cost-effective manner that is also beneficial to the district.

Rhode Island is home to 30 charter schools serving more than 7,000 students who make up about 5 percent of school children in the state. State law allows for three kinds of charter schools: district charter schools, independent charter schools operated by universities or nonprofit entities, and mayoral academies.55 All three kinds of charter schools are authorized by a single entity, the Rhode Island Council on Elementary and Secondary Education, and are granted for a term of five years.56

Central Falls School District, or CFSD, is located 10 miles north of Providence, Rhode Island, and serves 2,900 students in six schools. The student body is a diverse mix of Latino, African American, white, and multiracial students; 81 percent of CFSD students qualify for free or reduced lunch. CFSD students receive English language learner, or ELL, services—23 percent—and special education services—22 percent—at a higher rate than the state average, at 7 and 15 percent, respectively.57

In 2011, CFSD and six local charter schools signed a district charter collaboration compact and received a $200,000 planning grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.58 In the year before submitting the grant proposal, then-Superintendent Frances Gallo gathered charter leaders for periodic roundtable discussions to explore ways traditional and charter schools might collaborate. The conversations generated many ideas such as school facilities, talent pipelines, and ELL supports. But Jeremy Chiappetta, CEO of BVP, and Gallo became excited about an idea that previously had not sparked much interest for other charter school leaders: special education. 59 Both Chiappetta and Jen LoPiccolo, director of external affairs for BVP, credit the mutual respect between CFSD and BVP to the initial collaboration, as well as the continued joint work between the organizations.

Collaborating to better serve students

Opened in 2009, BVP serves more than 1,500 students from kindergarten through 11th grade across six schools. Approximately 14 percent of its students are eligible for special education services, a rate slightly lower than both the state and the CFSD average.60 As BVP grew as an organization, adding more schools and more grades, it also worked to grow its administrative infrastructure for special education.

From the establishment of the first elementary school in 2009 until the opening of the high school in 2014, BVP contracted with two retired special education administrators who each, in turn, served as part-time special education administrator for the organization. While each campus has a full-time special education chair and dedicated special education teachers, there was no one, LoPiccolo explained in a phone interview, devoted full-time at the network level to supporting the “building of a system that would ensure compliance procedures and connections with both families and the state was as good as it could be, and could do what it was intended to do.” As BVP contemplated further growth, it sought a full-time special education administrator.

Chiappetta noted that, for special education, “The best talent is actually found at the district.” Even before the district-charter collaboration began, CFSD had been working to augment its own internal capacity to deliver high-quality special education and related services, specifically focusing on opportunities to return students from private placements back to the district. This capacity made CFSD the natural choice for BVP to turn to in its search for a new full-time special education administrator. BVP entered into a six-month trial memorandum of understanding, or MOU, with the district, under which CFSD served as the special education administrator for BVP and provided BVP with access to special education services at an efficient scale. The MOU also included consulting hours from a CFSD expert to coach BVP school leaders and work to build internal capacity around special education.61

The key to the implementation of the work under the MOU is a former special education director and current chief academic officer at CFSD, Edda Carmadello, who also serves as BVP’s special education administrator under the MOU. In this role, she participates in BVP leadership meetings as a member of the organization’s cabinet; meets monthly with each head of school; and checks in with school-level special education and grade level chairs regularly throughout the year. While special education chairs at each campus are still the day-to-day managers of special education services for students, they can now access real-time coaching from Carmadello, an experienced special educator.

For her part, Carmadello highlighted specific interactions between BVP and CFSD staff as early evidence of success. The co-planning of secondary transition opportunities for students is one such interaction. Carmadello shared that CFSD has begun planning opportunities to expose middle and high school students to postsecondary opportunities but is still working to document the variety of opportunities students can access for career and life planning. During the 2015-16 school year, staff from BVP and CFSD spent Thursday mornings before school in a joint professional learning community, or PLC, reviewing best practices from around the state and crafting concrete opportunities for students from both systems to prepare for postsecondary transition.

Chiappetta and Carmadello were also proud of the trust and relationships that have been built across organizations as part of the collaboration. According to staff survey responses, “our special educators feel supported,” said Chiappetta. “There’s been really strong acclaim from both educators and leaders on this relationship.” Carmadello noted that BVP has no areas where it has fallen out of compliance, largely due to the way “we have risen as a team” to work through mediation hearings and difficult IEP meetings.

The developing relationships have also benefited CFSD staff. Carmadello identified getting district staff into BVP schools and classrooms to see the strength the CMO has around curriculum and instruction as having a “bilateral benefit” that has led to a “trickle of collaboration into other things, like math curriculum work.” She said that BVP sets high expectations for students and it “helps us to see this and be reminded of the need to maintain high expectations and rigor, too.”

Creating cost-effective solutions

Carmadello described in her phone interview that the first six months of the collaboration were a “getting to know you” period, during which she conducted a “deep dive into the practices at BVP.” Carmadello echoed what Chiapetta and the BVP already believed to be true—as the organization grew, it had not grown its systems for special education administration, and it benefited from sharing the already established systems within CFSD. After the initial trial period, CFSD and BVP signed a 12-month MOU in July 2015 to continue and deepen the collaboration on special education. The elements of the MOU remained the same, facilitated by a few key structural factors of both districts. One pillar of the BVP model is a longer school day and a longer school year. While CFSD employees end their contractual hours at 2:30 p.m., the BVP school day ends at 4 p.m. for students and 4:30 p.m. for staff. This daily difference allows CFSD employees—including service providers such as psychologists, bilingual speech-language pathologists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and adapted physical education teachers—to work with BVP students and be compensated without conflicting with their CFSD contracts. Summer hours at BVP are also a time when CFSD are not covered by their 185-day contract and can work on planning and professional development with the CMO.62

The MOU covers the 40 percent of Carmadello’s time as both a special education administrator and expert consultant, as well as hourly billing of direct services provided by CFSD staff. The former is billed at a rate of $6,650 per month, not to exceed $80,000 per year. The latter allows for three to five CFSD staff to provide services outside of contractual hours at the rate of $100 per hour for up to 100 hours per year. The pricing was set by CFSD and based on the community standard. The fact that BVP is an independent LEA means that all IDEA and state funds come directly to the CMO and it can then determine how to allocate them to serve students. Both the management contract with CFSD and some of the direct services are paid for using BVP’s state operating funds; other services are Medicaid reimbursable and processed by BVP and a third-party biller.63

Chiappetta noted that, as the collaboration continues to evolve, BVP will work with CFSD to “brighten the line between direct services and management [and] consulting services.” He said that, for the collaboration to be valuable to the district, it must be a “profit center for CFSD” and a way for the district to maximize the time and talent of their staff, while BVP benefits from the knowledge and expertise of that staff. The extended school day and year at BVP make the partnership financially viable for both systems, allowing CFSD staff to work as consultants in addition to their salaried roles at the district and providing BVP access to special education talent in the region without having to compete with the district. LoPiccolo stressed the importance of this benefit, noting that the BVP special education team has “varied levels of experience and the mentoring they get from Edda [Carmadello] is really building their capacity.”

Managing Challenges to Successful Collaboration

Focus on serving needs of kids

When the charters in Denver pushed back against the district’s original timeline for siting center programs, DPS’ Drake shared that there was a feeling among some within the district that the charter schools just didn’t want to have to serve the kids. Being able to come to a common table and listen authentically to why the charters pushed back was essential to the final outcome of a planning year prior to siting center programs in district or charter schools. Drake acknowledged that, while the district has deep expertise in special education, charter schools’ strong planning expertise led to the longer planning horizon for all schools, enabling both of these entities to better prepare to serve students. STRIVE Prep’s Coats shared that the task forces have worked because “everyone is coming to the table to figure this out.”

Establish clear processes and responsibilities

While the collaboration options in Los Angeles have led nearly all of LAUSD’s authorized charter schools to remain or rejoin the LAUSD SELPA, the process of collaboration has not been without challenges. Plate recalled challenges in developing the options solution. Initial discussions included a large group of charter leaders with a variety of interests. Narrowing down the number of voices in the room to make decisions was seen as important to the process, as was strong leadership from within the district. CCSA’s Plate credited then-Superintendent Ramon Cortines in her interview with efforts to move the COP proposal forward to board approval. LAUSD’s Quon added praise in her interview for Sharyn Howell, the former executive director of LAUSD’s division of special education, with making a crucial decision to getting buy-in from charters—to not discuss the cost of each option upfront, instead focusing on the levels of support that would be provided with each option.

While any collaboration can expect challenges, BVP’s LoPiccolo shared that most of the difficulties experienced in Rhode Island have been overcome. There were early hurdles such as confusion about whom staff could call for support and about all of the new faces in the BVP buildings. BVP and CFSD also needed to address a number of logistical challenges such as where to house people and whether BVP staff or CFSD staff would hold on to students’ special education files. CFSD’s Carmadello said that she feels good about how all of the early challenges were able to be addressed but would like to “get over the hurdle” of having her service providers work with BVP only after the CFSD school day.

Know your audience

Voluntary participation can provide a solid foundation for collaboration. Somewhat paradoxically, offering LAUSD charter schools options to rely on the district or to act as an LEA for special education purposes led to many charter schools seeking autonomy and then approaching the district as a valued, expert partner. The charter schools felt strongly about maintaining autonomy but were very comfortable with learning from and sharing with other schools. In offering a range of options that reflected their desire for autonomy and capacity for innovation, the LAUSD SELPA convinced nearly all of their authorized schools to become members and to innovate and build their capacity.

Build effective relationships

In Denver, DPS’ Drake was proud of the dramatically improved relationship between the special education department and the charter sector and credits the individual relationships between the liaisons and the charter school staff. “There a number of arrows pointing in the right direction in Denver to help us get going in the right direction,” Drake noted. Publicizing what is possible could therefore help other districts as they make efforts to evaluate how they support charters to serve all kids. Coats from STRIVE Prep echoed Drake’s comments on the progress thus far but was also eager to see how the partnership could be expanded. “Our collaboration can get better,” she said. “We can get far more accomplished when charters and districts work together.” That said, Coats expressed concern that there is also a need to be open to new ideas. For instance, Coats reflected that separate center-based special education programs are “a 40-year-old concept. Can we move away from this and think about how we fund kids, not programs?” She was eager to work closely with the district to “navigate the waters ahead” and do things differently.

Emerging collaborative efforts focused on special education: The Boston Compact

In the fall of 2011, the superintendent of the Boston Public Schools, the chair of the Boston School Committee, leaders from the Boston Alliance of Charter Schools, and the mayor of Boston signed the Boston Compact, a document that outlined plans for the traditional and public charter school sectors to collaboratively address issues that affected the quality of education available to all of the city’s children. This compact had grown out of local conversations between education leaders and national interest from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in cultivating cross-system collaboration. By the spring of 2012, the Archdiocese of Boston also joined the effort and signed on to the compact’s four main goals:

- A common enrollment calendar for all schools

- Cross-sector professional development strategies

- Common accountability metrics

- Better use of vacant city-owned school facilities

The compact work attracted more than $4 million dollars in financial support from the Gates Foundation and local philanthropies. This funding helped support both the issue-focused work and the operations of such a complex collaboration. A cross-sector steering committee with tri-chairs governs the compact, now entering its fifth year, and two full-time staff coordinate and facilitate meetings and provide administrative and communications support for the work.

While special education was not one of the original elements of the compact work, it emerged as one of six key initiatives outlined by the steering committee as part of a Gates Foundation grant proposal. Framed as an initiative to support practitioners in their work with students with disabilities, the compact committed to review legal and regulatory obligations of traditional and public charter schools; develop a system for securely sharing student records between schools across sectors; and analyze student data to identify and share exemplary practices for serving students.

In a recent report on the compact, School & Main Institute identified the overall return on investment of the Students with Disabilities, or SWD, Initiative as “moderate, with potential for greater impact in the future.” 64 This moderate impact is largely the result of two practical benefits of the initiative. The first benefit is student data sharing. The trust-building work of the compact led to five of the sixteen compact charter schools signing nondisclosure agreements with BPS and sharing all student-level data. While fairly straightforward, this was a big step forward in a city with significant student mobility and difficulties with student records transfer. A second benefit of the initiative grew out of the data sharing. Analysis of the student data identified classrooms within schools in both the traditional and charter sectors where “students with high levels of need were thriving in inclusive settings.” Teachers from all compact schools have been invited to observe in four schools where these best practice classrooms are located.

While the compact is moving forward with a revised structure that no longer calls out the SWD Initiative specifically, the collaborative efforts on special education are expected to continue as part of the compact’s teaching and learning subcommittee. It is worth watching the forthcoming work of the Boston Compact to see what additional collaboration around serving students with disabilities may emerge.