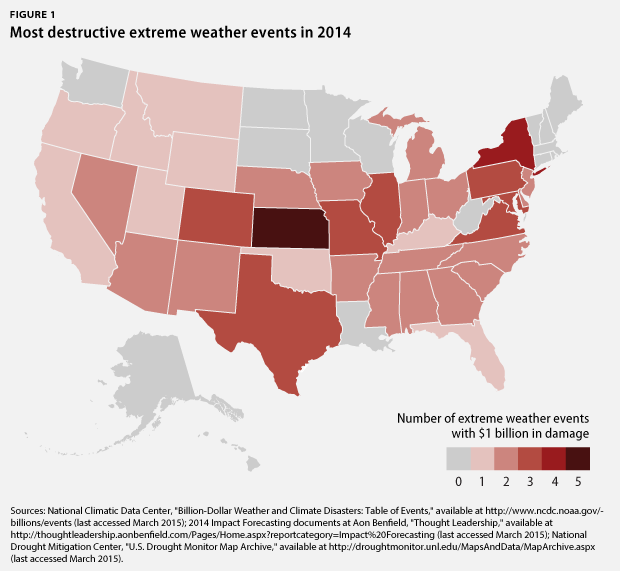

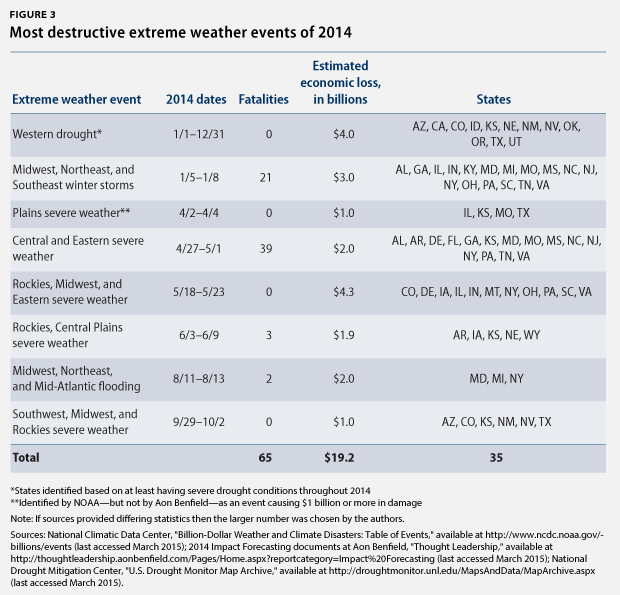

The United States experienced eight severe weather, flood, and drought events in 2014, each causing at least $1 billion in damage across 35 states. Overall, these disasters caused more than $19 billion in damage and took 65 human lives.

Building off of previous analysis, the Center for American Progress looked at disaster data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and Aon Benfield over the past four years and found that:

- There were 42 extreme weather events that each caused at least $1 billion in damage.

- These extreme weather events caused 1,286 fatalities and $227 billion in economic losses across 44 states.

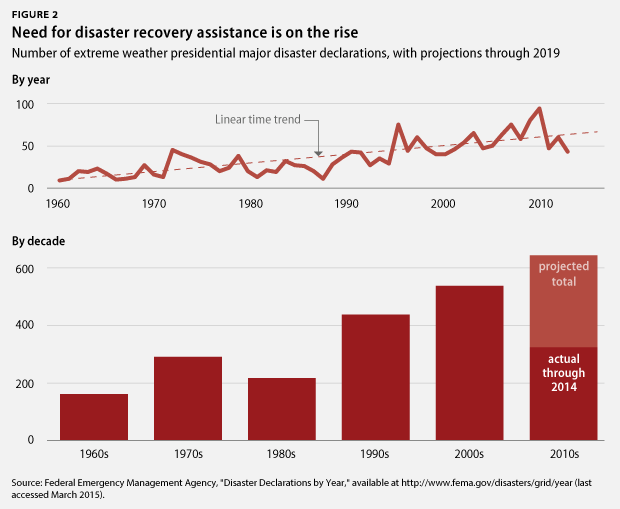

- On average, there were 61 presidential major disaster declarations per year because of extreme weather events.

According to the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, extreme weather events will become more severe and frequent as the climate continues to warm. While no single episode can be easily connected to climate change, the IPCC concluded that warming temperatures “can lead to changes in the likelihood of the occurrence or strength of extreme weather and climate events such as extreme precipitation events or warm spells.” Notably, 2014 was globally the hottest year on record.

Severe weather on the rise

While severe precipitation events tend to be the most deadly, the most expensive extreme weather disaster of the decade thus far is the Western drought, which has cost $46 billion to date, according to CAP analysis. University of California, Berkeley, Professor B. Lynn Ingram told The New York Times that California is “on track for having the worst drought in 500 years.” In order to protect perilously low freshwater resources, multiple states have taken increased measures to manage natural resources that are key to the region’s economy.

When extreme weather strikes, many communities request assistance from the federal government to manage the excessive costs. The government, in turn, may declare the event a major disaster. Each presidential major disaster declaration is based on careful deliberation by local, state, tribal, territorial, and federal officials. A declaration means the federal government will assist in providing resources to redress disaster zone residents, to rebuild infrastructure, and to restore the natural environment, offsetting economic costs for communities in need.

The fiscal considerations surrounding major disaster declarations are important because the number of these events is increasing. In only five years, the 2010s have witnessed almost as many extreme weather events as the 1960s and 1980s combined. By calculating a linear time trend based on the historical occurrence of declarations from 1960 through 2014, CAP projects that the 2010s may see a total of as many as 644 disasters by 2019. While only time can tell how many disasters will occur, this decade is well on track to surpass the last.

The need for a focus on resilience

Evidence shows that we are living in an era of extreme weather. If trends continue, the government must increase investments in resilience strategies, such as climate-smart pre-disaster mitigation, fortified infrastructure, sustainable resource management planning, and scientific research. According to a Multihazard Mitigation Council analysis, every $1 investment toward resilience reduces disaster damage by $4. In late 2014, the State, Local, and Tribal Leaders Task Force on Climate Preparedness and Resilience—an initiative of the Obama administration’s Climate Action Plan—released its recommendations to the president. The task force recommended that one way the United States can prepare for a more threatening future is by funding research programs and initiatives to execute resilient change and inform decision making at the state, local, and tribal levels. Many of these programs are proposed in President Barack Obama’s fiscal year 2016 budget request to Congress. CAP calculated that the budget request includes in the ballpark of $90 billion worth of programming to reduce disaster costs and build resilient infrastructure and communities—roughly a $25 billion increase over fiscal year 2015 appropriations.

Additionally, President Obama acted upon another recommendation of the bipartisan task force by establishing a federal flood risk management standard in January 2015. This new measure will ensure that federal agencies are financing taxpayer-backed infrastructure projects that are built to last in a more menacing environment. According to the White House, this standard will not affect the rates of the National Flood Insurance Program.

Congressional leaders from all 50 states should approve the president’s budget request, recognizing that the sizeable resilience investment would quadruple the benefits in fiscal protection and lifesaving measures for Americans. To provide additional resilience assistance to the communities most affected by extreme weather, Congress could establish a new state-level revolving loan fund for climate-resilient infrastructure, modeled after the successful revolving loan funds for drinking water and wastewater infrastructure.

Although the mounting fiscal burden of extreme weather should be considered from all fronts, the outsized consequences of these events on low-income communities must be addressed outright. Chronic underinvestment in infrastructure and living conditions in low-income areas—in addition to the location of many low-income households in flood plains or isolated rural regions—leave them particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. For some communities, recovery spending alone is not enough to regain stability lost during a disaster, and this adds to the need for resilience investments to avoid community disruption all together.

Conclusion

At only this decade’s halfway point, extreme weather events of all sizes have devastated Americans’ lives and their wallets to the tune of more than $227 billion—a sum that dwarfs the roughly $90 billion in resilience spending that the president’s budget proposal calls for in order to protect and fortify the nation’s future. Congress must act in accordance with the math, listen to the overwhelming warnings of the world’s best scientists, and heed the S.O.S. calls of its citizenry lest the United States succumb to the rising impacts of extreme weather.

Methodology

CAP’s analysis of extreme weather events and presidential major disaster declarations included only severe storms, winter storms, floods, high winds, droughts, and wildfires. The authors excluded from their analysis earthquakes; ocean tidal activity; lava flows; toxic algae blooms; tornados and mudslides that were not directly linked to extreme precipitation events and floods; and fires or chemical hazards due to infrastructure breakdowns or attacks.

Miranda Peterson is a Research Assistant with the Energy Policy team at the Center for American Progress. Alex Fields is an intern at the Center.

Thank you to Alison Cassady, Director of Domestic Energy Policy at the Center, Michael Madowitz, an Economist with the Center, and Cathleen Kelly, a Senior Fellow at the Center, for their contributions.