This column contains a correction.

“When the levee breaks, I’ll have no place to stay” is a line from an old blues song, popularized by Led Zeppelin. The song might see an unwelcome revival across the United States as the country’s outdated infrastructure—from bridges and roads to schools, rail lines, and reservoirs—strains to keep Americans safe from the effects of climate change.

The Republican leadership in Congress—currently in the process of drawing up a federal budget proposal for fiscal year 2016—has an opportunity to prevent this. Much like corporations, the federal government needs to understand and manage risks to its investments in order to make rational decisions about how to invest taxpayer dollars, reduce costly liabilities, and plan responsibly for the future. Sony Corporation learned this the hard way when it declined to invest $10 million to secure the company database, only to lose more than $270 million after it was hacked in 2011 and 2014. A growing body of evidence points to climate change as a serious risk that the federal government must manage to avoid costly consequences. By investing in infrastructure and communities that are resilient to climate change, Congress can reduce federal asset exposure to extreme weather risks; lower the costs to communities and taxpayers for disaster recovery and infrastructure maintenance; improve national security and public health and safety; and drive long-term economic growth.

In 2013, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave America’s infrastructure a D+ rating and recommended increasing investment in resilient infrastructure designed to “withstand both natural and man-made hazards, using sustainable practices, to ensure that future generations can use and enjoy what we build today.” According to the National Climate Assessment, or NCA, hazards such as sea-level rise, storm surge, and heavy downpours are overwhelming existing flood protections; this puts civilian ports—along with coastal military installations—at risk of damage. They are also compromising U.S. infrastructure, including roads, buildings, and industrial facilities. Furthermore, the NCA report warns that more extreme heat is undermining the integrity of roads, rail lines, and airport runways and that more intense storms are causing power outages that disrupt everything from public health to water services.

Since 2013, the Government Accountability Office, or GAO, has listed climate change as a top risk to federal operations, assets, and programs. In February 2015, the GAO put the federal government’s fiscal exposure to climate change threats at the top of its 2015 High Risk List report, citing the threat posed to hundreds of thousands of facilities and millions of acres of land. The U.S. Department of Defense’s facilities—worth $850 billion—and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s facilities—worth $32 billion—are particularly at risk, with many of them located in coastal areas.

The GAO concluded that climate change threatens many federal assets that Americans depend on daily—from public lands to water and flood protection infrastructure. Moreover, the GAO found that “State, local, and private sector decision makers can also drive federal climate-related fiscal exposures because they are responsible for planning, constructing, and maintaining certain types of vulnerable infrastructure paid for with federal funds, insured by federal programs, or eligible for federal disaster assistance.” For this reason, the GAO recommends that the federal government do more to help state and local decision makers manage climate change risks.

The substantial costs of climate inaction are not merely a challenge for the future. According to the Office of Management and Budget, extreme weather and fire alone have cost taxpayers $300 billion during the past decade. Climate change will only make future storms more frequent and costly. An analysis by Swiss Re indicates that a storm today causing $19 billion of physical damages and economic loss—the same amount of damage and loss caused by Superstorm Sandy in New York City—is considered a once-in-70-years occurrence. Taking climate change into account, however, models suggest that by the 2050s, the probability of a $19 billion event will grow to once in 50 years. Swiss Re estimates that, by the 2050s, such storms will cause a whopping $90 billion of damage in current dollars—almost five times the asset damage and economic loss caused by Sandy.

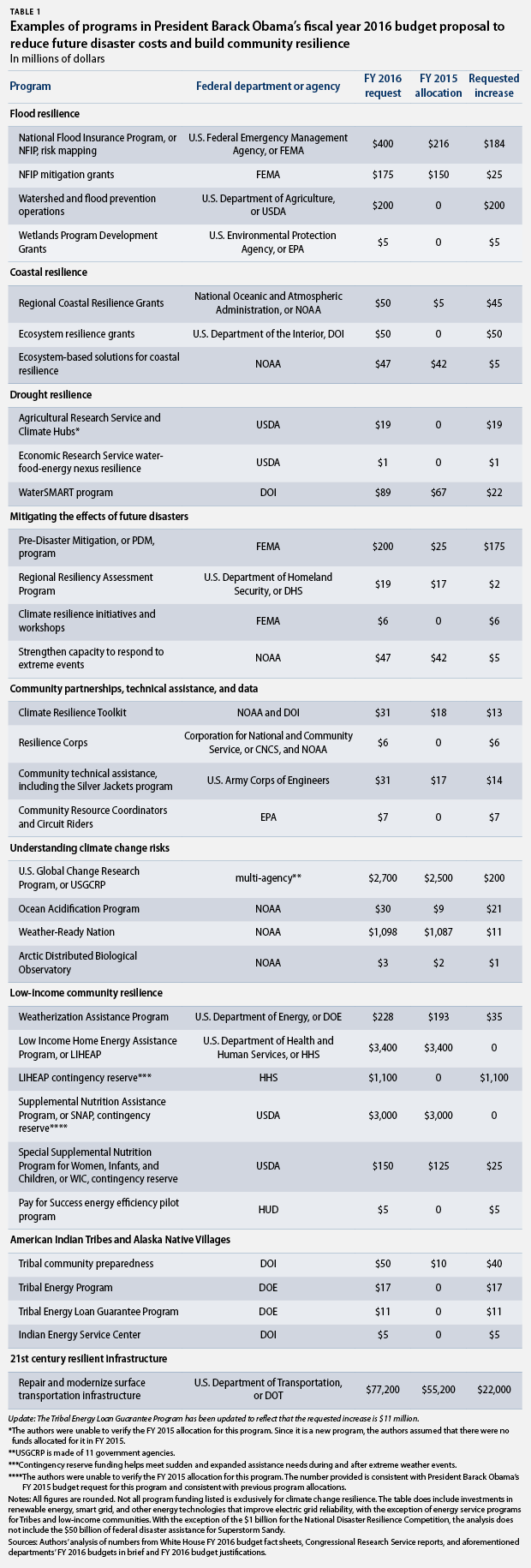

President Barack Obama recently took two significant steps to reduce the exposure of American communities and the federal government to the growing financial risks posed by climate change. First, the president’s FY 2016 budget proposal includes in the ballpark of $90 billion to reduce disaster costs and build resilient infrastructure, which is roughly $25 billion more than what was appropriated for resilience in fiscal year 2015. The president’s proposed domestic resilience investment includes $50 million to support climate preparedness for American Indian Tribes and Alaska Native Villages; $400 million to update our nation’s flood risk maps to help communities and business understand and lower their flood risks; $200 million to help state and local governments reduce extreme weather risks before disaster strikes; and $175 million to help National Flood Insurance Program policyholders reduce their flood risks, among other investments (see Table 1).

Second, in January 2015, the president established a new federal flood risk standard to ensure that federal agencies are investing taxpayer dollars in long-lasting infrastructure and buildings, including resilient drinking and wastewater facilities, roads, public transit, affordable housing, and power generation. The president’s new flood risk standard is consistent with the recommendations of a bipartisan task force of 26 state, local, and tribal officials from across the nation. In a November 2014 report to the president, the task force recommended that “federal agencies should adjust their practices in and around floodplains to ensure that Federal assets will be resilient to the effects of climate change, including sea level rise, more frequent and severe storms, and increasing river flood risks.” At least 350 communities across the country have already adopted similar standards to protect their homes, businesses, and infrastructure from disasters. According to the White House, the president’s flood standard will not affect the standards or rates of the National Flood Insurance Program.

Flood risk experts have responded positively to President Obama’s actions. Frank Nutter, the president of the Reinsurance Association of America, said in a statement that, “The President’s Climate Action Plan, and in particular, the new flood standard, will help stem the tide of rising property loss and increased risk to our citizens.” Chad Berginnis, executive director of The Association of State Floodplain Managers, endorsed the president’s flood risk standard and highlighted the shortsightedness of inaction by stating that, “To ignore the rising trends in flood damages—now exceeding $10 billion per year—and stay with the status quo is to accept that it is better to repeatedly waste taxpayer money repairing flood-damaged facilities that are not resilient to future flood risks.”

The new federal flood risk standard—along with the president’s proposed resilience investments for FY 2016, which CAP has championed—will help reduce disaster-recovery costs, lower public health and safety risks, and strengthen the nation’s long-term fiscal outlook. But even more investment and actions are needed to strengthen the nation’s climate change resilience, particularly in low-income areas. Decades of underinvestment in the housing and infrastructure of poverty-stricken areas, coupled with risky environmental conditions and economic instability, have left low-income families among the most vulnerable to more extreme storms, heat waves, floods, and other climate change threats.

The federal government must invest substantially more resources in strengthening resilience in low-income communities to address these deep inequalities. As directed in President Obama’s Climate Action Plan, federal agencies will also need to integrate climate change risk-reduction strategies into all federal grant and technical assistance programs, and federal infrastructure and natural resource management planning.

Sadly, many Republican congressional leaders have a poor track record when it comes to responsibly managing—or even acknowledging—the public health, safety, and national security risks of climate change. Sen. James Inhofe (R-OK), chairman of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, has turned his back on the consensus among experts that climate change is real and caused by human activity. Unfortunately, Sen. Inhofe is no outlier. According to an analysis by CAP Action, 56 percent of Republicans in the 114th Congress question or deny that climate change is driven by human activity, ignoring vast amounts of scientific evidence to the contrary.

Ignoring the risks of climate change is both dangerous and costly. A Multihazard Mitigation Council study concluded that each dollar invested in resilient infrastructure and other actions to reduce disaster losses saves as much as $4 in disaster-recovery costs. Superstorm Sandy alone cost taxpayers $50 billion in disaster-recovery costs; Americans simply cannot afford further delays by Congress on needed resilience investments.

When Congress fails to invest in strategies to cut carbon pollution and build the nation’s resilience to more extreme weather, they put taxpayer investments, businesses, and the health and safety of Americans at risk. This head-in-the sand management approach is fiscally irresponsible and unethical.

Singing the blues is one thing; allowing Americans to live them due to federal neglect is another altogether.

Correction March 13, 2015: The table was updated to remove the National Disaster Resilience Competition, which was from the post-Sandy disaster supplemental appropriation and not part of the president’s FY 16 budget request.

Cathleen Kelly is a Senior Fellow at American Progress. Miranda Peterson is a Research Assistant for the Energy Policy team at American Progress.

The authors would like to thank Greg Dotson, Danielle Baussan, Tracey Ross, Kyle Schnoebelen, Emily Haynes, Alex Tankou, Emily Ludwigsen, Anne Paisley, and Jason Chow for their contributions.