Report chapters

Why the middle-class squeeze matters

The American middle class is in trouble.

The middle-class share of national income has fallen, middle-class wages are stagnant, and the middle class in the United States is no longer the world’s wealthiest.

But income is only one side of the story. The cost of being in the middle class—and of maintaining a middle-class standard of living—is rising fast too. For fundamental needs such as child care and health care, costs have risen dramatically over the past few decades, taking up larger shares of family budgets. The reality is that the middle class is being squeezed. As this report will show, for a married couple with two children, the costs of key elements of middle-class security—child care, higher education, health care, housing, and retirement—rose by more than $10,000 in the 12 years from 2000 to 2012, at a time when this family’s income was stagnant.

As sharp as this squeeze can be, the pain does not stop at one family, or even at millions of families. Because of the critical role that middle-class consumers play in creating aggregate demand, the American economy is in trouble when the American middle class is in trouble. And the long-term health of the U.S. economy is at risk if financially squeezed families cannot afford—and smart public policies do not support—developing the next generation of America’s workforce. It is this workforce that will lead the United States in an increasingly open and competitive global economy.

This report provides a snapshot of the American middle class and those struggling to become a part of it. It focuses on six key pillars that can help define security for households: jobs, early childhood programs, higher education, health care, housing, and retirement. Each chapter is both descriptive and prescriptive—detailing both how the middle class is doing and what policies can help it do better.

Defining the middle class

Statistically, when we talk about the middle class, we generally mean the middle three quintiles of American households by income—those making between the 20th and 80th percentiles of the income distribution. In reality, however, being middle class in America is at its core about economic security. As Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA) wrote in the 2011 report “Saving the American Dream,” “Most of us don’t expect to be rich or famous, but we do expect a living wage and good American benefits for a hard day’s work.”

At the Center for American Progress, our work has focused on the importance of both strengthening and growing America’s middle class. So while the middle three quintiles will always be just that, it is our goal to ensure that as many Americans as possible have the cornerstones of the American Dream, including access to education, health care, housing, and the ability to retire.

So even as this report measures what has been happening to the middle class, we articulate our hopes for all Americans. To be clear, having more than 46 million Americans in poverty is both contrary to our national character and to our economic aspirations. So too is having millions of young people unemployed and underemployed and 11 million aspiring Americans living in the country without legal status.

Having more workers in good jobs—who have access to good education; affordable child care, health care, and housing; and the ability to retire with dignity—is our clear objective. The closer we get to this reality, the better it will be for all of our families and the sustainable growth of our economy.

What’s more, we know that areas with larger middle classes and less inequality also have more economic mobility. And opportunity is what America is about: 97 percent of Americans believe that every person should have an equal opportunity to get ahead in life. We all have an interest in a strong and growing middle class.

Squeeze part I: A snapshot of incomes

When we think about the golden age of the American middle class, we often think of the decades following World War II. To be sure, the mid-20th century legislated unequal treatment and therefore limited opportunities for many Americans, but even with that marked and deep-rooted inequality, the economic statistics from that period tell a story of growing wealth and security for America’s middle class.

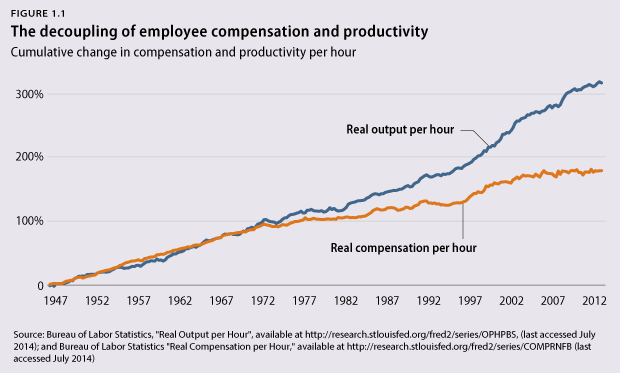

From 1948 to 1973, America experienced a period in which growing compensation tracked growing worker productivity: A worker in 1973 was almost twice as productive as a worker in 1948 and earned nearly twice as much. This golden age built the middle class as prosperity was increasingly shared. The economy grew by an average of 3.9 percent from 1948 to 1973, and the bottom 90 percent of families reaped 68 percent of the gains.

However, around 1973, American productivity growth slowed, increasing about half as quickly between 1973 and the early 1990s as it had during the previous 25 years. Furthermore, compensation started to decouple from productivity, growing about one-third as quickly as before.

As the 1990s tech boom progressed and the economy heated up, productivity accelerated again: Productivity growth from 1991 to 2012 averaged 2.2 percent per year, yet compensation growth only averaged 1 percent per year. A worker today is almost 60 percent more productive than a worker in 1991 but has seen only half of that productivity growth translate into higher compensation. And the vast majority of this wage growth took place toward the end of the 1990s tech boom, as real wages and benefits jumped about 16 percent between 1995 and 2001.

Real compensation growth has slowed further since the start of the 21st century. What’s worse, health insurance premiums over this period ate into even modest compensation gains. Therefore, many Americans saw stagnant or declining take-home pay even as productivity continued to rise.

In other words, American workers have been squeezed for decades when it comes to take-home pay, even before 2007 and the Great Recession. The financial crisis and the Great Recession itself then took a catastrophic toll on millions of Americans, as unemployment skyrocketed and trillions of dollars in household wealth vanished. And while the economy has picked up since bottoming out in 2009, and private-sector job growth began to bounce back in 2010, the gains from this postcrash period have been strikingly unequal. Ninety-five percent of all income gains since the start of the recovery have accrued to the top 1 percent of U.S. households.

The trends in rising inequality are also striking when measured by wealth. Among the top 20 percent of families by net worth, average wealth increased by 120 percent between 1983 and 2010, while the middle 20 percent of families only saw their wealth increase by 13 percent, and the bottom fifth of families, on average, saw debt exceed assets—in other words, negative net worth. Families of color have fallen further behind white families in building wealth: A survey that tracked white and African American families between 1984 and 2009 found that the wealth gap between them nearly tripled, from $85,000 to $236,500. Homeowners in the bottom quintile of wealth lost an astounding 94 percent of their wealth between 2007 and 2010.

The importance of the middle class to economic growth

Rising inequality is not simply a question of distribution; it also poses real questions for how our economy operates. The increasing resources available to the wealthiest Americans have created demand for such luxuries as private jets—which creates jobs building those jets—but the declining purchasing power of middle-class Americans means that there is less demand for goods and services more broadly in the economy. A recent analysis showed that giving $1 to a low-income household produces three times as much consumption as giving $1 to a high-income household. And it is certainly true that increasing the concentration of wealth means more jobs managing finances and fewer jobs making the goods that middle-class consumers once bought in numbers that drove much of our economic growth.

CAP outlined the economic importance of a strong and growing middle class—and the concerns for our economy from growing inequality—in a 2012 report, “The American Middle Class, Income Inequality, and the Strength of the Economy.” The report details the importance of the middle class to human capital, stable demand, entrepreneurship, and support for institutions.

Squeeze part II: A snapshot of rising costs

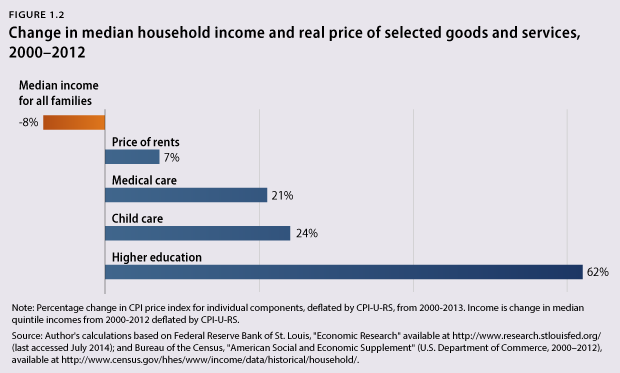

While real incomes have been stagnant or declining in recent years, the other side of the story is the increase in the costs of various items that define a middle-class standard of living. Not only have families’ costs for things from higher education to health care increased rapidly relative to overall consumer inflation, but these costs are also consuming a growing share of family budgets, leaving less and less room for discretionary spending and saving.

When looking at the changes in consumer price indices for core elements of middle-class security, it is painfully easy to see the squeeze in action; prices for many cornerstones of middle-class security have risen dramatically at the same time that real incomes have fallen.

As stark as the data appear when comparing stagnant or falling incomes to rising prices, they are even worse than the Consumer Price Index above might suggest.

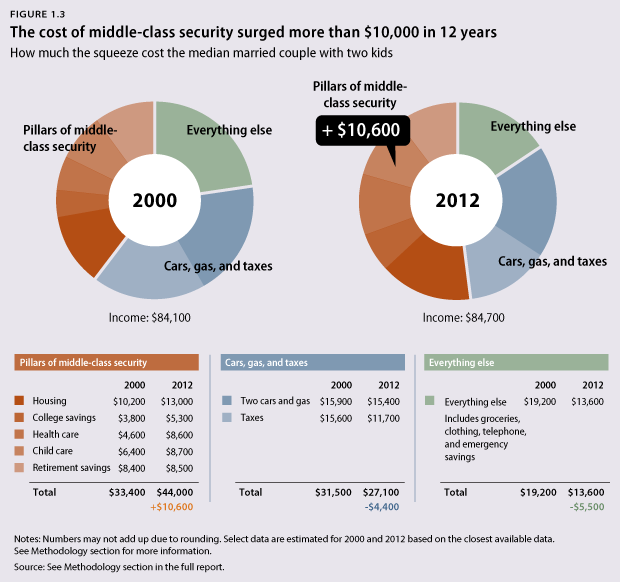

Let’s consider what has happened to the finances of a typical middle-class family since 2000.

The median family saw its income fall by 8 percent between 2000 and 2012. Even when we look at just married couples with two children—a type of family that tends to have higher incomes—median income was virtually frozen between 2000 and 2012.

At the same time, this type of family also faced a severe middle-class squeeze as the costs of key elements of security rose dramatically, including child care costs—which grew by 37 percent—and health care costs—both employee premiums and out-of-pocket costs—which grew by 85 percent.

In fact, investing in the basic pillars of middle-class security—child care, housing, and health care, as well as setting aside modest savings for retirement and college—cost an alarming $10,600 more in 2012 than it did in 2000.

Put another way, in 12 years, this household’s income was stagnant—rising by less than 1 percent—while basic pillars of middle-class security rose by more than 30 percent. As the cost of basic elements of middle-class security rose, the money available for everything else—from groceries to clothing to emergency savings—fell by $5,500. And while for the purposes of this example we have assumed this household kept retirement savings constant, data about worryingly low savings confirm that for millions of families, their retirement funds are bearing much of the pain of the squeeze.

The data paint a clear picture: The middle class is being squeezed. So it should come as no surprise that in a 2014 Pew Research Center survey, 57 percent of Americans responded that they think their incomes are falling behind the growing cost of living, up from 47 percent in 2006. In fact, the percentage of Americans who identify themselves as middle class has fallen to 44 percent, down from 53 percent in 2008.

Policies to alleviate the squeeze

Understanding that middle-class families are clearly squeezed—with adverse effects on our entire economy—we must craft policies to alleviate the squeeze. This requires two things: growing incomes and containing costs.

Jobs

Given that the majority of middle-class families derive their incomes from jobs—as opposed to investments—improving our lackluster jobs picture is the first task to address the middle-class squeeze. To do this, we need to invest in a dynamic economy powered by skilled workers who operate in an environment that lets them and their businesses compete at home and abroad. Doing so will require myriad policies outlined in depth in CAP’s long-term growth strategy,

300 Million Engines of Growth: A Middle-Out Plan for Jobs, Business, and a Growing Economy. Five areas that would directly help the jobs and income pictures in the shorter term include policies to:

- Boost aggregate demand, including through extending federal unemployment insurance; raising the federal minimum wage to $10.10 per hour; strengthening the Earned Income Tax Credit by expanding it for workers without children and lowering the eligibility age from 25 to 21; and making long-term investments in our economic growth that will also pay dividends now in the form of expanding high-quality early childhood education and infrastructure

- Foster inclusive capitalism that will see more gains shared with workers, including through expanding tax incentives that transfer ownership or at least a share of profits from capital ownership to employees; offering grants to regional inclusive capitalism centers; stopping policies that inhibit the growth of sharing programs; and promoting existing best practices through an Office of Inclusive Capitalism

- Ensure basic workplace protections to maximize workforce participation, including through developing a federal paid family and medical leave program to ensure working families have access to wage replacement when they need it most, via the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act, or the FAMILY Act, as well as establishing a national paid sick days standard via the Healthy Families Act

- Strengthen unions, including by modernizing the union election process; ensuring that all workers, regardless of their occupation or location, have the right to join a union if they so desire; better protecting workers who choose to unionize by making the right to join a union a civil right; and establishing more meaningful penalties and remedies for workers who are fired or discriminated against for exercising their right to organize

- Improve education and workforce-development programs, including a dramatic expansion of apprenticeship programs in high-growth sectors, by creating a $1,000 federal tax credit for each apprentice hired; establishing competitive grants to support promising apprenticeship partnerships in new high-wage, high-growth occupations; improving apprenticeship marketing to businesses; leveraging the federal workforce and federal contracting to support apprenticeships; and improving the portability of apprenticeships by offering grants for employers to come together to write national guideline standards for apprenticeships in key high-growth occupations

Early childhood programs

High-quality early childhood programs—including both child care and preschool programs—are critical for workers with young children who hope to remain in the workforce. Research shows that these programs are also critical educational investments in the children themselves. So with two generations relying on the existence and affordability of high-quality programs, it is critical to address the high cost of child care, which rose dramatically from 2000 to 2012. To do so, we recommend policies that would:

- Provide high-quality preschool to all 3- and 4-year-olds through a partnership between the federal and state governments

- Expand and reform the child care subsidy system, which is currently insufficient to reach even a majority of low-income working parents, let alone those struggling to stay in the middle class, by both providing additional resources to help families access high-quality child care and ensuring that child care assistance declines gradually as parents earn more money, rather than cutting off abruptly

- Reform the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit by making it refundable and raising the amount that can be claimed to cover more of the actual cost of child care

- Expand Early Head Start-Child Care Partnerships building on the initial investment already made and reaching additional children

Higher education

Increases in higher-education costs are a huge part of the middle-class squeeze. These costs affect what parents can do to help their children pay for college and what students can bear in terms of debt as they enter an uncertain job market. What’s more, the real and perceived costs of higher-education affect who applies for and who goes to college—representing a real constraint on economic mobility, which carries a cost for individuals and for the economy. To help alleviate the middle-class squeeze in higher education, we propose policies that would:

- Promote consumer choice by establishing a student-record system that can be used to create improved consumer-choice tools that highlight outcomes such as graduation rates and labor-market outcomes, and by creating a federal accountability system with institutions placed in broad categories, rather than rankings, which indicate their performance across key metrics

- Restore public investment in higher education, including through increasing funding for the Pell Grant program to help low- and lower-middle-income students; creating a competitive federal grant program to support public institutions—matched with state funds—to support state policies that promote on-time completion and that significantly lower the cost of postsecondary education

- Innovate to bring down costs and improve quality through increasing support for the First in the World Fund; using experimental site authority to give institutions flexibility from existing federal requirements in exchange for a commitment to implement innovative programs that reduce costs for students; creating an alternative to accreditation where institutions could choose to focus exclusively on improving the learning outcomes of their students; and increasing investment in research and development.

Health care

Access to affordable health care is critical for all American households, and the rising costs of health care in recent decades have kept a basic underpinning of middle-class security out of reach for too many. While the Affordable Care Act, or ACA, has already made a difference for millions of Americans—from the ability of children under age 26 to remain on their parents’ health insurance plans to a prohibition on exclusion from coverage based on pre-existing conditions—more needs to be done to bend the cost curve and to ensure that people have access to high-quality coverage. A single health event should not wipe out a person’s savings. To help lower costs, we therefore propose policies to:

- Accelerate the use of alternatives to fee-for-service payment to reduce costs and improve care coordination, with Medicare leading the way by encouraging private payers to participate in alternative payment methods, especially bundled payments

- Leverage insurance exchanges to improve access to lower-cost, high-quality insurance products, including through state marketplace officials using their broad authority to exclude low-value plans and reward plans that offer more value to consumers

- Increase transparency to allow consumers to choose high-quality, lower-cost providers and services via the Department of Health Human Services, ensuring that the ACA’s requirement to provide cost-sharing information is implemented in a consumer-friendly way. Congress should also modify the ACA’s cost-sharing disclosure requirements so that the plan’s quoted costs for episodes of care are guaranteed

- Reform restrictive state scope-of-practice laws to maximize use of nonphysician providers, with the federal government providing bonus payments to states that meet scope-of-practice standards delineated by the Institute of Medicine

- Address cost shifting to employees by encouraging employers to share health care savings with employees via more transparency, with employers providing annual notices about how much the employer expects to pay, on average, for health care benefits per employee, as well as how much the employer expects the employee will spend, on average, for health care during the upcoming year

Housing

Having an affordable place to call home is out of reach for far too many families, putting the most basic piece of middle-class security in doubt. New mortgages are at their lowest level in 17 years, millions of Americans still owe more than their homes are worth, and half of all renters spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. The federal government has a huge role to play in steering the country out of the housing crisis and building a stronger and more equitable housing-finance system. To do so, we suggest policies that would:

- Require Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to support a healthier and more equitable housing market by increasing access to and affordability of mortgages, providing struggling borrowers with better loan modifications that include principal reductions, and capitalizing the National Housing Trust Fund and Capital Magnet Fund

- Reform the housing-finance system to realign incentives, enable broader access to affordable and sustainable mortgages, and support the creation of more affordable rental housing

- Track cash investor activity in the single-family rental market and monitor its potential impact on tenants, rents, neighborhoods, and homeownership opportunities

Retirement

Among the top concerns of middle-class Americans is whether they will be able to afford to retire. Unfortunately for many, saving for retirement has become much more difficult in recent decades as families have struggled to find money to save and as the workplace-retirement-plan environment has fundamentally changed. As incomes have stagnated and as employers have shifted away from pensions to 401(k)-style plans, employees have been forced to shoulder far more risk and to invest what little they can set aside in savings vehicles that are often designed to take advantage of their lack of investment experience. With approximately half of all American households in danger of having insufficient savings for retirement, we propose policies that would:

- Encourage the adoption of hybrid retirement plans such as CAP’s Safe, Accessible, Flexible, and Efficient, or SAFE, Retirement Plan at both the state and national levels

- Increase access to existing alternative savings options such as the low-cost Thrift Savings Plan which—by allowing all workers the ability to join—would not only give many a chance to save through a workplace plan but also would provide them with access to one of the best 401(k) plans available

- Require 401(k) and IRA plans to be more transparent about fees and investment practices through the adoption of a retirement label on all qualified plan options that informs consumers about the high risks of fees and lets them know how the fees in a given plan compare with fees in other plans of the same type

- Make tax incentives for saving simpler and fairer by replacing the complex web of tax deductions that disproportionately benefit the wealthy with a Universal Savings Credit that would turn all existing deductions into a single, streamlined credit, as well as by potentially introducing a progressive match for low-income savers’ contributions

Conclusion

To have a strong and growing economy, we need a strong and growing middle class. The longer the middle-class squeeze continues unabated, the more these trends will continue to affect both families across the country and our economic prospects as a nation.

We know what policies would help reverse the middle-class squeeze. Now, we just need to act.