See also: “America’s Leaky Pipeline for Teachers of Color: Getting More Teachers of Color into the Classroom” by Farah Z. Ahmad and Ulrich Boser

In the fall of 2011, the Center for American Progress released an issue brief looking at teacher diversity, and the findings were stark. We found that the demographics of the teacher workforce had not kept up with student demographics. In that study, we showed that students of color made up more than 40 percent of the school-age population. In contrast, teachers of color were only 17 percent of the teaching force.

Since we released our first report on teacher and student demographics, the nation has only grown more diverse. One factor driving this trend is birth rates among populations of color; there has also been a 50 percent increase in the country’s Hispanic population over the past 20 years. Immigration has also played a significant role in our nation’s changing demographics, which include a marked uptick in the number of people moving to the United States from abroad since the Great Recession.

At the same time, states have not being doing nearly enough to increase the diversity of their teaching ranks. In 2011, for instance, North Carolina slashed funding for its Teaching Fellows Program. The program had a dedicated focus on recruiting people of color, and experts had hailed it as an important way to get more teachers of color into the nation’s classrooms.

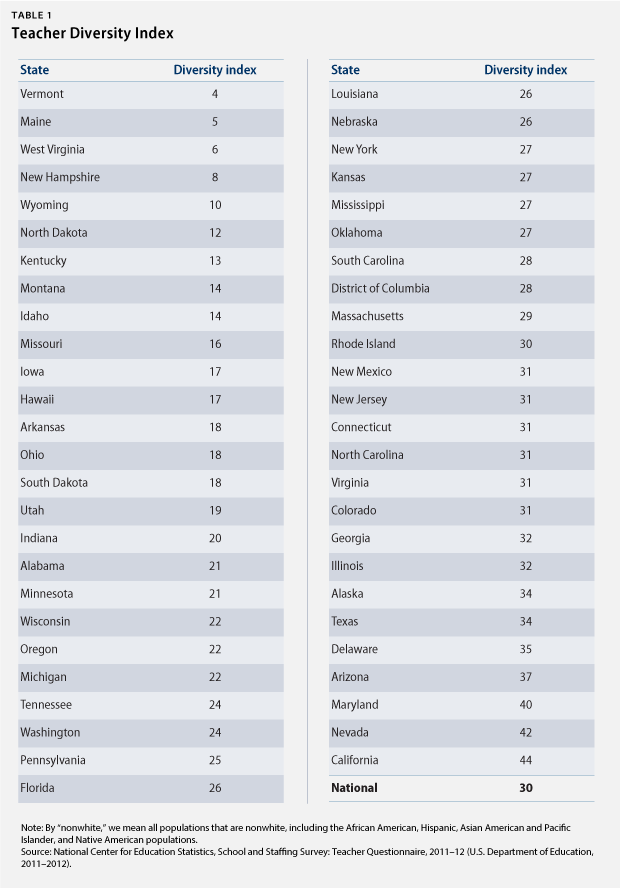

Given these trends, we decided to revisit the issue of teacher diversity, and we calculated again our groundbreaking “Teacher Diversity Index,” an approach we pioneered in our first paper that ranks states on the percentage-point difference between teachers of color and students of color. For our analysis, we relied on data from the 2012 Schools and Staffing Survey, a nationally representative survey of teachers and principals administered every four years by the National Center for Education Statistics.

We also relied on 2011 data from the Common Core of Data, which is also administered by the National Center for Education Statistics. And for the first time, we looked at teacher diversity within some select states. It should be noted that in this brief, we define “nonwhite” as anyone who is African American, Hispanic, Asian, or Native American.

Among our findings:

- The gap between teachers and students of color continues to grow. Over the past three years, the demographic divide between teachers and students of color has increased by 3 percentage points, and today, students of color make up almost half of the public school population. But teachers of color are just 18 percent of the teaching profession. This is a 1 percentage point increase from three years ago. When we looked more closely at the state-level data, we found similar issues, with the diversity gap growing larger in most states. In New York, for instance, the demographic difference between teachers and students has jumped 5 percentage points since 2011.

- Almost every state has a significant diversity gap. In California, 73 percent of students are nonwhite, but only about 29 percent of teachers are nonwhite. Maryland has the same problem, though the numbers are a bit better: In the Old Line State, more than 55 percent of students are nonwhite, while just around 17 percent of teachers are nonwhite.

- When we looked across racial and ethnic backgrounds, we found that the Hispanic teacher population had larger demographic gaps relative to students. In Nevada, for instance, just 9 percent of teachers were Hispanic. In contrast, the state’s student body was 39 percent Hispanic.

- Diversity gaps are large within districts. For the first time, we examined district-level data in California, Florida, and Massachusetts. These three states account for 20 percent of all students in the United States, and it turns out that the gaps within districts are often larger than those within states.

Consider these examples of teacher-diversity issues uncovered by our research:

- In the Chelsea Public Schools in Massachusetts, there is a 76 percentage-point gap between the percentages of Hispanic teachers and students.

- In the Hardee County Schools in Florida, 58 percent of students are Hispanic, while only 8 percent of teachers are Hispanic.

- In the Randolph Public Schools in Massachusetts, 52 percent of students are African American, but less than 5 percent of the district’s teachers are African American.

Implications for teachers and students of color

Taken together, these findings have significant ramifications for students and schools. Teachers of color can serve as role models for students of color, as we noted in our previous report, and when students see teachers who share their racial or ethnic backgrounds, they often view schools as more welcoming places.

Students of color also do better on a variety of academic outcomes if they are taught by teachers of color. Or, as education professors Richard Ingersoll and Henry May have argued, “minority students benefit from being taught by minority teachers, because minority teachers are likely to have ‘insider knowledge’ due to similar life experiences and cultural backgrounds.” What’s more, it is important for all students to interact with people who look and act differently than they do in order to build social trust and create a wider sense of community. In other words, the benefits of diversity are not just for students of color. They are also important for white students.

Given these benefits, why are there such large diversity gaps between teachers and students? In other words, if teachers of color bring so much to the academic table, why don’t states and districts do more to bring them into the classroom?

There is no single reason for this disconnect; multiple factors are at play. Part of the issue is market forces, as we have noted in previous reports, and today, people of color have far more job choices than ever before. Furthermore, the K-12 system itself is partially to blame; there are large racial gaps in high school graduation rates, which means that fewer people of color attend college relative to their white peers.

Moreover, the structure of the teacher career ladder further complicates this issue. The fact that the profession currently has significant incentives for people to stay in the teaching profession for long periods of time means that white teachers who entered the profession 20 years ago often stay until they retire. This lack of churn means that there is less opportunity for teachers of color to enter the teaching workforce.

Whatever the root cause of the lack of diversity among the teacher workforce, one thing is clear: States and districts have not done enough to address the issue. Few states have created rigorous programs to help individuals of color enter the teaching profession. Not nearly enough districts have offered bonuses or other benefits to people of color who are interested in becoming educators. To make matters worse, in some cities, such as Boston, the number of black teachers is actually declining.

Looking deeper at the problem

To gain a better handle on what’s happening across the nation, we ranked states on the demographic differences between their teacher populations and their student populations.

Arizona, for instance, has an index score of 37. To obtain that figure, we subtracted the percentage of nonwhite teachers—20 percent—from the percentage of nonwhite students—57 percent—in the state. For specific breakouts by state, see Appendix A.

This index ranks states on the percentage-point difference between the percentages of nonwhite teachers and nonwhite students. Also, please note that the student data came from the Common Core of Data and dates back to the 2010-11 school year. The teacher data is from the Schools and Staffing Survey and is from the 2011-12 school year. Both datasets are the most recent available.

As part of this study, we also looked at district-by-district data in the few states that make this information available, and what we uncovered was troubling. In fact, in some school districts, the teacher workforce looked almost nothing like the student body.

In the Santa Ana Unified School District in California, for instance, 93 percent of students are Hispanic, while only 26 percent of teachers are Hispanic—a nearly 67 percentage-point gap. Or think of it this way: In Santa Ana, fewer than 3 percent of students are white, while 65 percent of teachers are white.

The lack of teacher diversity was particularly high in the largest school districts in the three states where data were available. In the Los Angeles Unified School District, for instance, 74 percent of students are Hispanic, while just around 34 percent of teachers are Hispanic. In Boston, nearly 40 percent of students are Hispanic, while only 10 percent of teachers are Hispanic—a 30 percent percentage-point gap.

There are also large gaps between black students and black teachers in Boston, and the city’s percentage of black teachers has fallen so low—it’s currently at 21 percent—that the city is currently in violation of a federal court order to ensure diversity in its teacher workforce.

As in the state-by-state data, there are few Hispanic teachers in our nation’s classrooms relative to the number of Hispanic students. The San Diego Unified School District, for instance, has a 30 percent percentage-point gap between the percent of Hispanic students and the percent of Hispanic teachers. In California’s Long Beach Unified School District, there was a nearly 35 percent percentage-point gap between Hispanic students and teachers.

Conclusion

Although the numbers are stark, there are solutions that will work to ensure that the teachers standing in the front of the classroom mirror the students filling the seats, and we can do far more as a nation to improve the diversity of our teacher workforce. As researchers Saba Bireda and Robin Chait argued in the 2011 CAP report, education leaders have a wide number of policy options that have been shown to improve the demographics of the teaching profession.

Bireda and Chait suggest, for instance, that states should do more to fund teacher-preparation programs. They also argue that the federal government can do more by creating financial aid programs for low-income students to help them deal with the costs of teacher preparation. Perhaps the most successful approach, though, has been providing students of color with supports—including mentorship and practicums—and financial incentives.

But in the end, the solutions to improving teacher diversity might boil down to something more fundamental: political will. After all, it’s clear that we need to do far more to bring teachers of color into the classroom. The question is, when will our political leaders step up to make sure that this issue gets addressed? Even more importantly, when will parents, activists, education leaders, and other reform advocates demand that classroom teachers reflect the communities they serve?

Ulrich Boser is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress.