Introduction and summary

“I felt like I was throwing him to the wolves every day.” This is how Jennifer describes the experience of sending her son Isaiah to preschool.

A bright, sensitive boy adopted at a young age, Isaiah struggled with his school’s rigid environment from the moment he first arrived until his family eventually moved after third grade. Isaiah entered preschool after receiving early intervention services for developmental delays and was still entitled to individualized services, but something in his behavior wasn’t right. Fire alarms were overstimulating, causing him to race around the room and push classmates if they came too close. Unable to settle him down, teachers isolated Isaiah from his peers or sent him to the principal’s office. Isolation was especially painful for Isaiah, as his early experience in foster care left him with separation anxiety. Visits to the principal’s office failed to change his behavior; at a young age, Isaiah could not understand her role as an authority figure, and chafed at rules he saw as unreasonable and unfair. As a result, teachers labeled him as defiant and aggressive, which led a painful cycle of overstimulation, disruptive behavior, removal from class, fear and loneliness.

When doctors finally diagnosed Isaiah with attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) at age 7, it cast new light on his classroom behavior. Isaiah wasn’t defiant or aggressive; he was navigating a world of sensory overload and unfathomable social rules. He was still receiving services through his Individualized Education Program (IEP), but was now entitled to additional supports for his ADHD and ASD. Unfortunately, these diagnoses did not change how his school disciplined him. Fed up, Jennifer and her family seized the opportunity to move to a new school district at the end of Isaiah’s third grade. Today, Isaiah attends sixth grade in a different school that understands and supports him.

Sadly, too many young children with disabilities and social or behavioral difficulties are currently living a version of Isaiah’s harrowing early learning experience. According to new data, children ages 3 to 5 with disabilities and or emotional and social challenges, while comprising just 12 percent of early childhood program populations, represent 75 percent of suspensions and expulsions. The odds of being suspended or expelled are more than 14.5 times higher for children with disabilities and emotional challenges than for their typically developing peers. (see Appendix)

The consequences of this disciplinary reality are devastating. Suspensions and expulsions lead to lost learning time and also deprive children, especially those with disabilities, of valuable opportunities that can help them overcome early challenges. Moreover, removing children with disabilities from classrooms can deprive them of crucial services available under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). 1

This report presents a new analysis—detailed in the appendix—highlighting the prevalence of suspensions and expulsions among young children ages 3 to 5 attending early childhood programs. It also provides background on these exclusionary disciplinary practices; presents analysis of recent nationally representative data; and explains the consequences of expulsions and suspensions for all children, specifically children with disabilities. Finally, it provides recommendations to ensure that all young children—particularly those with disabilities—reap the full benefits of early learning, including:

- Prohibit suspensions and expulsions across early childhood settings

- Develop alternatives that proactively address children’s emotional and behavioral needs

- Invest in teacher professional development

- Reduce teacher stress

- Empower teachers with tools to fight implicit bias

- Promote meaningful family engagement

Evidence clearly shows that high-quality early learning experiences allow children of all backgrounds to acquire critical social, cognitive, and academic skills. Disciplining children by removing them from the classroom disrupts this process, resulting in long-term negative consequences. Moreover, when programs apply discipline in a discriminatory manner, they may exacerbate inequalities based on race, gender, and physical and mental disabilities. Policymakers should consider implementing policies that limit punitive disciplinary practices and ensure all children receive a strong start.

Background

Children in preschool and early childhood programs are suspended or expelled at a rate three times higher than school-aged children.2 However, exclusionary discipline practices might not always carry these labels—suspended and expelled. Suspensions take several forms in early childhood settings, including sending a child to the principal or director’s office, or asking a family member to pick a child up early because of behavioral issues. Expulsions can be “hard”—such as when a program informs the family that they must find a new care arrangement—or “soft”—practices that make the care arrangement untenable, such as repeatedly asking the family to pick up a child for behavior issues.3

Whether or not early disciplinary practices are explicitly labeled as suspensions or expulsions, these practices are an inadequate and inappropriate way to address challenging behavior. First, exclusionary disciplinary practices are developmentally inappropriate for any young child and fail to produce positive behavioral results. Instead, from a child’s perspective, these punitive measures inexplicably sever early ties to peers and teachers just as they are taking root. Removing children from early learning environments also stigmatizes young individuals, contributing to numerous adverse social and educational outcomes.4 Research shows that young children who are suspended or expelled are more likely to experience academic failure and hold negative attitudes toward school, which contributes to a greater likelihood of dropping out of school and incarceration.5

Second, a growing body of evidence suggests that these suspensions and expulsions may reflect gaps in teachers’ training and unconscious biases rather than children’s behaviors.6 Teachers with insufficient training in child development may place inappropriate demands on children’s behavior, such as expecting young children to sit still for long periods. Moreover, in 2012, only 20 percent of early childhood teachers and providers reported receiving training on children’s social and emotional development.7 This kind of training is critical to teachers’ ability to screen for developmental, behavioral, or medical challenges. Given this context, had Isaiah been subject to early screening and intervention, it’s likely his school experience would have resulted in a different outcome.

Implicit bias exacerbates the problems arising from teachers’ gaps in training and contributes to racial and gender disparity in preschool expulsions. Specifically, a recent report by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights showed that although African American children represent only 18 percent of preschool enrollment, they make up nearly half the total suspensions.8 Young African American boys are doubly disadvantaged; indeed, researchers discovered that early childhood teachers were more likely to look for challenging behaviors among African American boys than among any other group.9

Finally, early suspensions and expulsions deprive children of valuable early opportunities that can help them overcome early challenges. Research shows that children who are most likely to be suspended or expelled—children from low-income families, children of color, and children with certain disabilities—are also most likely to benefit from high-quality early education.10 Children from low-income families and children of color are more likely to experience multiple adverse childhood experiences (ACES), which can manifest as challenging behaviors that trigger suspensions or expulsions.11 Likewise, young children with language delays or trouble with self-regulation may struggle to verbalize appropriate responses to emotional or physical stimulation, and instead display inappropriate behavior.12 In both cases, appropriate evaluation and intervention services can help children learn important coping and communication skills. However, suspending and expelling children from preschool makes it less likely children receive these critical services.

Acknowledging these problems, the Obama administration previously issued guidance to school districts. The first, a joint policy statement issued by the U.S. departments of Education and Health and Human Services, focused on reducing suspensions and expulsions in early childhood settings.13 The second, a guidance package released by the departments of Education and Justice, addressed discrimination in school disciplinary practices.14 Unlike laws or regulations, these guidance documents are not legally binding. However, they provide a standard against which schools or programs may be judged if there are complaints to the Office of Civil Rights. Education officials from the Trump administration have recently met with advocates claiming that the guidance documents undermine discipline and make schools unsafe. This suggests that Education Secretary Betsy DeVos may consider delaying or dismantling some of these protections, leaving children with disabilities at greater risk.15

Children with disabilities face higher odds of being expelled

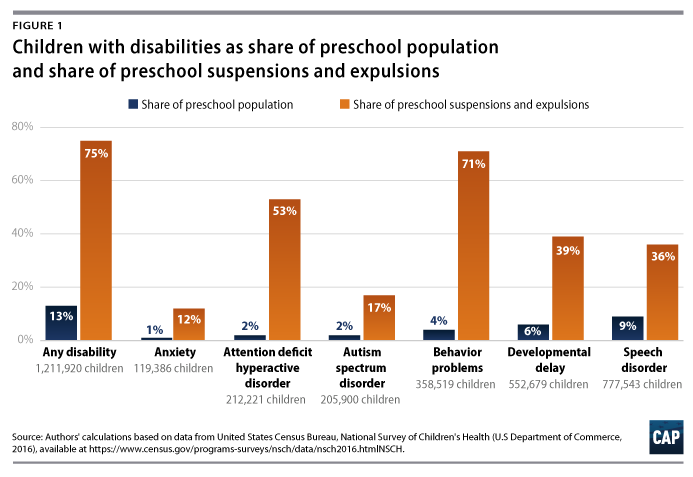

New data reveal that although children with disabilities represent a relatively small proportion of the population of children ages 3 to 5 attending preschool, they make up a disproportionately large share of suspensions and expulsions. Children with any disability or social-emotional challenge make up only 13 percent of the preschool population, but they constitute 75 percent of all early suspensions and expulsions. A similar pattern of overrepresentation can be found across all disability conditions.

Note that these data are descriptive statistics that do not account for child or family characteristics that could contribute to a child’s greater likelihood of being disciplined. It is possible that other traits, such as race or family poverty, could be driving this effect. Additional regression analyses show that compared with their typically developing peers, and after controlling for several child and family characteristics, the odds of being suspended or expelled were still more than 14.5 times larger for children diagnosed with any disability or social-emotional challenge. In addition, compared with their typically developing peers:

- The odds of being suspended or expelled were more than 43 times higher for children with behavioral problems.

- The odds of being suspended or expelled were 33 times higher for children with ADHD.

- The odds of being suspended or expelled were more than 14 times higher for children with anxiety.

- The odds of being suspended or expelled were 10 times higher for children with autism/ASD.

- The odds of being suspended or expelled were more than 7.5 times higher for children with developmental delays.

- The odds of being suspended or expelled were more than 4 times higher for children with speech disorders.

Consistent with earlier research, the odds of being suspended or expelled for African American boys in this sample were between 3 and 5 times greater than the odds of other children being similarly disciplined. Non-Hispanic white boys were also more likely to be suspended or expelled than other children, but by a smaller margin—3 to 4 times higher odds. Although the sample size precluded the authors from being able to investigate the added effects of race and disability on preschool discipline, previous research suggests that children of color with disabilities are among the most likely to be suspended or expelled.16

The findings above are based on the authors’ analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2016 National Survey for Children’s Health (NSCH), the first nationally representative survey to include questions on early discipline using a sample of children attending both public and private early learning programs. The analysis predicted the odds of being suspended or expelled based on whether a child currently had a disability or challenges with social-emotional issues. (see Appendix) Previous reports have relied on data from public preschool programs. However, since private programs are not required to report suspensions and expulsions, earlier reports likely underestimated the frequency of exclusionary disciplinary practices in early childhood settings. Moreover, earlier reports rely on data from “hard” expulsions, whereas the NSCH contains information on preschool disciplinary practices that do not carry the suspension or expulsion labels. The NSCH’s way of capturing preschool discipline more accurately captures the nature of suspension and expulsion in preschool. This report therefore provides more accurate information on disciplinary practices across all early childhood settings.

Consequences of expulsions and suspensions

Children’s early years lay the foundation for later success. Suspensions and expulsions—two stressful, stigmatizing experiences—deprive children of opportunities to develop friendships, learn new skills, and gain independence and self-efficacy. This is harmful for all children, but can be especially damaging to children with disabilities. Suspensions and expulsions communicate that adults have low expectations for children, which children internalize and translate into disengagement from school.17 Over the long term, this disengagement can lead to truancy, dropping out of school, and incarceration.18

Beyond their immediate and long-term impact on individual children, suspensions and expulsions may violate federal civil rights laws if administered in a discriminatory manner. Administrative law requires that programs ensure children with disabilities are not suspended or expelled for behaviors related to their disability. If a child’s behavior disrupts others’ learning, early childhood programs must consider implementing reasonable policy and practice modifications that reduce the need for discipline.19 As most children in this study were currently diagnosed with a condition that made them eligible for IDEA services, findings suggest that disciplinary practices in early childhood settings must do better to protect the civil rights of children with disabilities.

Finally, removing children with disabilities and children of color—many of whom come from low-income families—removes children who are likely to make the greatest gains from high- quality preschool.20 Expelling children who are most in need of high-quality, supportive early learning undermines preschools’ mission of preparing children for kindergarten.21 These children are also likely to provide the biggest return on investment in services; by expelling children who most need services, programs undercut the economic model of early education.22

Policy recommendations

The findings of this report affirm what parents such as Jennifer already know—the early childhood system must do better to ensure that children with disabilities are able to fully participate in valuable early learning experiences. Improving how early childhood programs address disciplinary practices will require systemwide structural and cultural changes. At a minimum, districts should defend the progress made during the Obama era by protecting the previous administration’s guidance documents against potential repeal by the current Department of Education.23 Policymakers can further catalyze these changes by implementing the following recommendations:

Prohibit suspensions and expulsions in early childhood settings

The most direct way to eliminate the practices of suspending and expelling young children is to ban them in early childhood settings. States and school districts are leading these efforts. For example, Maryland24 and Texas25 both passed laws that took effect in the summer of 2017 prohibiting suspensions and expulsions in preschool through the second grade. Tennessee also passed a law in May 2017 requiring the state’s department of education to review all current laws and practices related to exclusionary discipline in preschool and kindergarten, as well as develop alternatives based on its review.26 Policymakers should look to these laws as models for their own state and local governments.

Develop alternatives that proactively address children’s emotional and behavioral needs

Some behaviors—such as Isaiah’s pushing of classmates—may be driven by underlying developmental challenges. Policymakers should therefore adopt the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommendation to assess children at risk for expulsion for developmental, behavioral, and medical challenges. This practice can help connect children to interventions that address the underlying issue, thereby reducing disruptive behaviors.27 Policymakers can also promote the use of school-based counseling and mental health programs as an alternative to exclusionary discipline by providing funding and technical assistance to programs. For example, early childhood mental health consultants (ECMHC) are skilled professionals who help preschool and child care teachers gain the skills they need to manage challenging classroom behavior.28 These services can also be used with other practices or services that prevent or de-escalate challenging behaviors. One example is a multitiered system of support (MTSS), a comprehensive framework for organizing practices or services into different tiers that correspond to children’s needs.29

Invest in teacher professional development

Research shows that promoting children’s positive social and emotional development prevents and reduces challenging classroom behavior.30 However, early childhood teachers frequently report a pressing need for further training and professional development on evidence-based practices for addressing challenging behavior and supporting social and emotional development.31 Districts should make professional development and training opportunities more widely available to teachers.

Reduce teacher stress

Teaching young children with challenging behavior can be stressful. Moreover, teachers are often poorly compensated and subject to undependable hours.32 When teachers experience long, irregular hours or high student-teacher ratios, they can feel overwhelmed and tired. Teachers in these circumstances are more likely to suspend or expel children, regardless of the severity of a child’s behavior.33 To avoid this situation, policymakers should ensure programs provide teachers with reasonable, dependable work hours with regular breaks; maintain low student-teacher ratios—for instance, at or below the National Association for Education of Young Children’s (NAEYC) ratio of 10 preschoolers per teacher; and provide teachers with other respite and mental health services as needed.34 Improving teachers’ compensation and benefits can also help ease economic insecurity, another contributor to teacher stress.35

Empower teachers with tools to fight implicit bias

Research shows that implicit bias contributes to disproportionate disciplinary practices. When teachers and program directors expect poor behavior from students based on unconscious stereotypes related to a student’s race or physical or mental ability, they may spend more time looking for this behavior.36 Requiring programs to develop formal policies and procedures for managing discipline can reduce disproportional disciplinary practices by making discipline less subjective. If programs define challenging behavior in clear, measurable terms that reflect developmentally appropriate behavioral expectations, staff will make more fair and consistent disciplinary decisions. Although implicit biases are part of being human, teachers and other program staff are more likely to rely on them when they must make quick, stressful decisions. Fortunately, by consciously working to recognize and overcome bias and maintaining high expectations of all children,37 staff can stop them from having a negative effect. Programs should consider offering training on topics such as promoting equity, reducing prejudice, and working with specific special needs populations in the community.

Promote meaningful family engagement

Children of all backgrounds and abilities benefit when families and schools work together. For families of children and youth with disabilities, it is particularly important that parents understand their child’s condition and receive clear information about accommodations to which children are entitled. Knowledge about children’s rights is critical to the exercise of informed choice and children’s full participation in their communities, beginning in preschool.38 Policies should explicitly support two-generation strategies involving both parents and children and comprehensive wraparound services to families.39 In the early learning period, it is critical that families start to think about individualized planning documents across different programs, how they interact, and how they can lay out future transition goals and plans. As early on as possible, schools, and communities should cultivate networks of parents of children with disabilities to serve as another resource, provide a support system, and model high expectations.40

Conclusion

When Isaiah’s school continued to discipline him despite clear signs that he needed support rather than punishment, Jennifer was fortunate enough to be in a position where she could relocate her family to a supportive setting that has helped Isaiah thrive. However, this is not an option for most people. Children such as Isaiah—and indeed, all children—benefit from a welcoming, inclusive environment that is sensitive to their needs.

Evidence clearly shows that high-quality early learning experiences allow children of all backgrounds to acquire the crucial social, cognitive, and academic skills needed to succeed in school and beyond. Removing children from classrooms through suspensions and expulsions disrupts this process, resulting in long-term negative consequences. Moreover, when programs apply discipline in a discriminatory manner, they may exacerbate inequalities based on race, gender, and physical and mental disabilities. More importantly, they deny children access to valuable early learning experiences and critical early intervention services to which they may be entitled. Ensuring children’s equal access to high-quality early learning not only pays significant dividends in the long run; it is fundamental to guaranteeing students’ civil rights.

Appendix

The authors used the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), a large survey of all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The survey provides rich data on children’s physical and mental health, access to quality health care, and the child’s family and community context. The NSCH—which had been previously conducted in 2003, 2007, and 2011—is the only national and state-level survey on the health and well-being of children and families. Households were contacted at random to identify those with one or more children under 18 years old. In each household, one child was randomly selected to be the subject of the survey. Surveys were administered in 2016 via web and paper-based instruments sent to parents.41 The survey oversampled children with special health care needs and children ages 0 to 5.42 Results are weighted to represent the population of noninstitutionalized children ages 0 to 17.

Sample

The analysis was restricted to children ages 3 to 5 years who were currently enrolled in preschool or child care and answered questions about preschool disciplinary practices (n=6,100). When weighted, the sample represents 9.03 million children ages 3 to 5 who were enrolled in preschool when the data were collected. About half the weighted sample were boys, 88 percent spoke English at home, 68 percent identified as non-Hispanic white, 14 percent identified as African American, and 18 percent identified as “Other” race.

Variables

The following variables were created:

Disability categories

The 2016 NSCH contains several questions that ask parents whether their child had a current diagnosis of different medical and behavioral conditions. For this report, the authors restricted the analysis to conditions that make children eligible for Part B 619 preschool special education under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) or emotional challenges that could affect classroom behavior.43 Only conditions with sufficiently large sample sizes were included. Although the following conditions make children eligible for special education services, they were excluded due to small sample size: traumatic brain injury (n=21), cerebral palsy (n=15), intellectual disability (n=29), and Down syndrome (n=7). Based on these two criteria, the following conditions were selected: learning disability, ADHD, anxiety, behavior problems, Autism/ASD, developmental delay, and speech delay.

Suspension and expulsion

The 2016 NSCH included a question asking parents of children ages 3 to 5 about preschool and child care disciplinary practices. Parents were asked whether they had been asked to keep their child home from any child care or preschool because of their behavior in the past 12 months. Using parent responses, the authors of this report defined a suspension or expulsion as being any situation where a parent was asked to keep a child at home for a full day or more (out-of-school suspension) or being informed that a child could no longer attend the program (“hard” expulsion). This definition represents a “hard” suspension or expulsion, a stricter definition of preschool discipline. Parents also reported being asked to pick up their child early on one or more days. This action on the part of early learning programs constitutes a “soft” expulsion if it results in families finding different care arrangements. For this analysis, the authors selected a “hard” definition, as it is more conservative.

Descriptive analysis

For each disability category, the authors calculated the share of the preschool and child care population these children represent and the share of preschool suspensions and expulsions these children represent. This was done by running individual crosstabs for each disability and “hard” expulsions, using survey weights.

Regression analysis

The analysis used logistic regression with survey weights to predict the odds of being suspended or expelled, based on whether a child currently had a disability or behavioral or social difficulty. As the outcome of interest—removal from the classroom through either suspension or expulsion—was a dichotomous variable, a logistic regression was most appropriate. Survey weights adjust the estimates to be nationally representative. Regression models controlled for several child characteristics that could also affect the likelihood of being suspended or expelled. These included a child’s gender, race, home language, and the family poverty ratio.

Limitations

As with all regression analyses, it is possible that other variables not included in the model also predict the odds of suspension or expulsion. In particular, some evidence suggests that disciplinary practices vary across school or program type—for example, publicly funded prekindergarten, private child care, or other. As this data set did not make this information publicly available, the model used in this analysis is likely biased due to omitted variables.

About the authors

Cristina Novoa is a policy analyst for Early Childhood at the Center for American Progress. She studied developmental psychology and public policy, specializing in the academic and behavioral development of children from immigrant families. She holds a doctorate in developmental psychology and a master’s degree in public policy from Georgetown University as well as a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Yale University.

Rasheed Malik is a senior policy analyst for Early Childhood at the Center where he focuses on child care infrastructure and supply, the economic benefits of child care, and the disparate impacts of early childhood policy. He received a master’s degree in public policy from the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rebecca Cokley for her guidance and insight, as well as Katherine Gallagher Robbins for her helpful review of the report’s data and methods. Special thanks to Jennifer and Isaiah for sharing their stories.