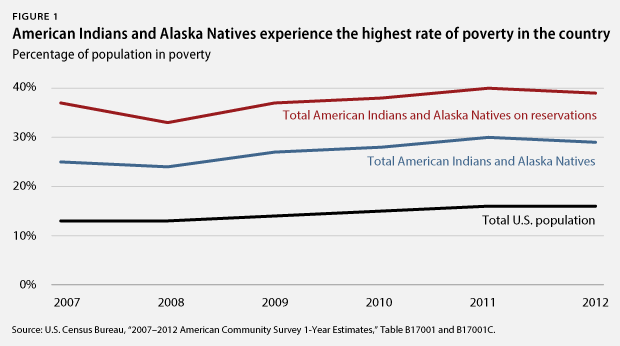

The extremely high rates of poverty among American Indian and Alaska Native, or AI/AN, communities were at the forefront of President Barack Obama’s mind as he addressed the annual White House Tribal Nations Conference earlier this month. Referencing the deep and chronic nature of the problem, the president put it in stark terms: “That’s more than a statistic, that’s a moral call to action. We’ve got to do better.” According to the most recent Census Bureau estimates, nearly one in three AI/AN people—29.1 percent—lived below the federal poverty line in 2012, which stood at $23,492 for a family of four. For AI/AN peoples living on a reservation, the rate is a far-higher 38.6 percent. This compares to the overall U.S. poverty rate of 15.9 percent.

This month, our country celebrates both Thanksgiving and Native American Heritage Month. It’s a time to reflect on the important role that American Indians and Alaska Natives have played in our country’s history. We spend too little time, however, examining the policies that affect tribal governments and the communities they support today. For AI/AN peoples, these statistics are not just a moral call to action; they also represent a serious legal failing of our federal government to honor the treaty obligations it made to AI/AN peoples generations ago—obligations to provide basic services that promote good health, education, and economic growth.

Instead of waking up to the alarm of these high poverty rates, Congress seems to continually hit the snooze button, especially as it considers yet another year of sequestration, which has already seriously and disproportionately impacted AI/AN peoples. As governments, tribes must deliver a wide range of critical services, such as education, workforce development, and first-responder and safety services, to their citizens. Tribal governments also maintain major infrastructure such as housing and roads. Much of this funding comes from the federal government, so when Congress makes cuts, especially indiscriminate cuts through reckless policies such as sequestration, the effects on reservation and urban AI/AN communities are immediate, severe, and damaging.

It’s time for Congress to answer this moral and legal call to action so that AI/AN peoples can finally look forward to prosperity and progress for future generations, rather than some of the worst and most chronic rates of poverty, health, and education.

A young and fast-growing population stuck in the recession

The AI/AN population is growing fast in our country. Between the 2000 and 2010 U.S. Censuses, the total AI/AN population grew from 4.1 million to 5.2 million people, a 27 percent increase. During the same period, the overall U.S. population grew by about 9.7 percent. The AI/AN population is also very young; the median age in 2012 for AI/AN peoples was 31 years, compared to 37.4 years for the overall U.S. population.

But high rates of poverty for AI/AN peoples living both on and off the reservation represent a long and disturbing trend for this fast-growing population. From 2007 to 2010, the poverty rate for AI/AN peoples remained at nearly double the national rate. For those living on reservations, the poverty rate was even higher—nearly 2.5 times the overall rate.

The recession also hit this population disproportionately hard. The unemployment rate for American Indians jumped 7.7 percentage points to 15.2 percent between the first half of 2007 and the first half of 2010, 1.6 times higher than the increase for the white population. By the first half of 2010, unemployment for Alaska Natives was even higher, at 21.3 percent. In 2012, the rate for AI/AN peoples living on reservation lands was 22.8 percent, compared to the national rate of 15.9 percent.

These persistently high poverty and unemployment numbers stem from other disparate and challenging outcomes. AI/AN peoples born today are expected to live 4.1 years less than their non-native counterparts. They also die from certain diseases at far higher rates. AI/AN peoples die from alcoholism, for example, at a rate that is a staggering 552 percent higher than those of all other races, and they die from diabetes at a rate that is 182 percent higher. While high school graduation rates for every other racial and ethnic group have shown recent improvement, AI/AN students still have the worst educational attainment rates in the country. In fact, they have seen only modest improvements since 2000, and they are the only group that has seen their graduation rate actually decline since 2008.

A legacy of severe underfunding and the harsh impacts of sequestration on AI/AN communities

The federal government has a unique obligation to improve these outcomes and create a sustainable path to prosperity for AI/AN peoples, but it has instead chosen to continue a disappointing legacy of seriously underfunding critical programs. The Indian Health Service, for instance, is currently only funded to meet about 56 percent of its need, despite being the primary provider of health care for many tribal communities. Most AI/AN children go to public schools, but many of these schools do not have a reliable tax base and disproportionately rely on Impact Aid funding, which makes up for the lack of funding on and near reservations and military bases. The Impact Aid program has not been fully funded since 1960.

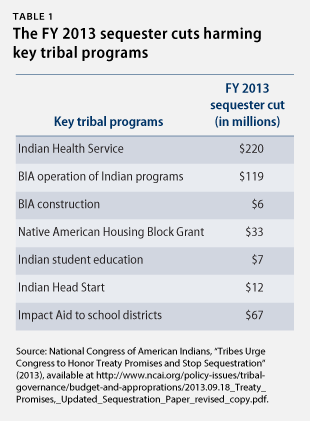

On top of this past underfunding, health, education, and other areas of service are subject to sequestration. By allowing reckless across-the-board cuts to go into effect for fiscal year 2013, Congress is unfairly putting deficit reduction on the backs of the approximately 115,000 AI/AN students affected by Impact Aid education cuts; the 25,000 AI/AN children hurt by Head Start cuts; the 1.7 million AI/AN peoples hurt by the $119 million removed from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA, budget; the 88,000 AI/AN students in tribal colleges losing programs and courses; and the 2.1 million people affected by the $220 million cut to the Indian Health Service. These FY 2013 cuts will be exacerbated if Congress does not cancel or replace sequestration in FY 2014.

Reductions from FY 2013 that are setting Indian Country back are collected in the table below.

Meeting our obligations to AI/AN peoples will build broader economic opportunity

The challenges for AI/AN peoples also hold back tremendous opportunity and potential economic success. Although low high school graduation rates persist, the number of AI/AN peoples with postsecondary degrees has more than doubled in the past 30 years. AI/AN-owned businesses have also been on the rise, increasing nearly 18 percent from 2002 to 2007. As the rest of the American economy continues to recover, tribes also offer new opportunities for the communities that surround them. According to a recent Oklahoma City University study, Oklahoma tribes employed 53,747 people, generated $2.5 billion in state income, and produced $10.8 billion in state goods and services in 2010. In Idaho, tribes were among the top 10 employers in the state in 2010.

Although tribes have made some progress in addressing egregiously inadequate public services that many Americans routinely take for granted, such as law enforcement, education, and infrastructure development, they are still seriously and disproportionately challenged by what the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights called “a quiet crisis” of federal funding and unmet needs. The reckless policy of sequestration is just the latest in this ongoing trend. In a recent hearing before the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, Karen Diver, chairwoman of the Fond du Lac Tribe in Minnesota, shared her perspective on sequestration:

[Congress] is asking us to be wizards in our own community. We are to promote community development. We are to promote economic development. We are to promote health. We are to promote safety. We are to do all these things without a tax base. [Sequestration] is … taking away our ability to rise up and help support rural communities—not just Indian communities—but entire rural communities with the employment and the economic spin off. … Those steps back are going to cost us more in the long run. I think I’m pretty good at my job, but I am not that good. We need folks to stand firm in their convictions and speak up in the budget negotiations. When push comes to shove, we need people to say, “Not in Indian Country: it’s too important, the situation is too dire, we’ve come too far.”

Conclusion

Even in the face of persistent and severe underfunding, AI/AN governments and communities have made progress in addressing egregiously inadequate public services that many Americans have the luxury of taking for granted. But reckless policies such as sequestration are setting AI/AN peoples back generations. If Congress is serious about rebuilding the economy and improving the lives of those who face the deepest and most persistent poverty in our nation, it should start by replacing or canceling sequestration instead of promoting policies that abandon legal obligations and harm opportunity for our nation’s first peoples.

Erik Stegman is the Manager of the Half in Ten Education Fund at the Center for American Progress. Amber Ebarb is a budget and policy analyst at the National Congress of American Indians.