Last year, students at New York City public schools missed tens of thousands of school days due to suspensions. These students were not sick or skipping. Through the overuse of suspensions and expulsions, U.S. public schools fail to serve large segments of historically disadvantaged students. Policymakers must focus on ensuring that public schools fairly serve all the students entrusted to them.

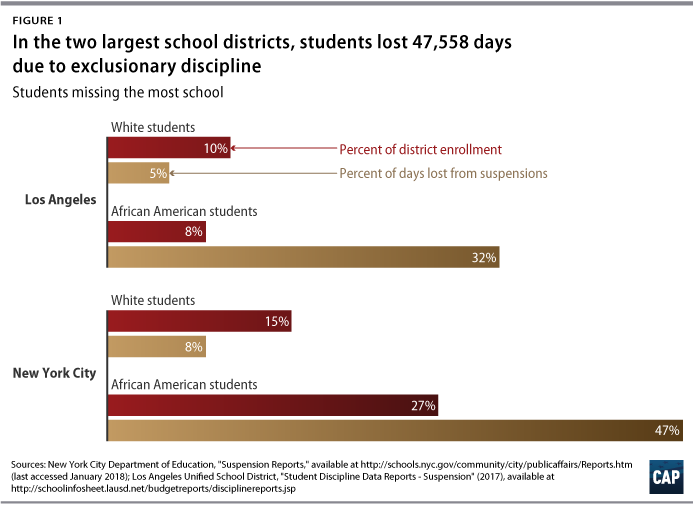

During the 2016-17 school year, the country’s two largest school districts—the New York City Department of Education (NYCDOE) and the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD)—suspended or expelled students for a total of 47,558 days. To its credit, a few years ago, the LAUSD restricted suspensions for nonviolent offenses and implemented restorative practices in its schools. Because of these initiatives, it suspended students for far fewer days than did the NYDOE.

New Center for American Progress analysis of these district data uncovered huge racial disparities in the days missed. White students make up 15 percent of the NYCDOE but only account for 8 percent of the days lost due to suspensions. Meanwhile, African American students comprise 27 percent of the district but account for almost half—47 percent—of the days lost due to suspensions. Similarly, African American students account for just 8 percent of LAUSD enrollment but 39 percent of days suspended. The reasons for the suspensions vary in severity, but these racial disparities exist for both minor and serious infractions.

While these specific statistics are new, research shows that schools have overdisciplined African American and Latino students—as well as students with disabilities and English language learners—for at least 40 years. Every other year since 1968, the Office of Civil Rights has conducted the Civil Rights Data Collection, chronicling public school programs and, over time, the rates of seclusion, restraint, and exclusionary discipline practices. Because of these data, in 2014, the U.S. Department of Education reiterated the legal limitations of exclusionary discipline and reminded school districts of their responsibility to serve all students. The department also highlighted research-based practices that improve student behavior and school climate in order to help educators eliminate arbitrary treatment of students and create more positive school environments.

Still, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, with the support of conservative advocates, recently signaled interest in rescinding this guidance. One of these advocates is Michael Petrilli, the head of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. In print, quotes to the press, and social media, Petrilli has expressed doubt over the extent of racial bias in discipline and has argued for the removal of federal discipline guidance, maintaining that it makes schools and students less safe.

The Fordham Institute initially opposed the Obama administration’s guidance under the belief that its supporters attribute the “entirety of the gap … to racial bias in the system,” arguing that “the racial suspensions gap [can] be explained by differences in behavior that are driven in large part by those same background factors [that affect the achievement gap],” such as poverty, fatherlessness, and low levels of parental education. However, to the contrary, there is racial bias in discipline practices because poverty rates or levels of misbehavior do not entirely explain the disparities. Factors such as disengagement from school, gender, or poor student-teacher relationships must be considered as well. Furthermore, students who feel controlled or coerced often suffer from a lack motivation and engagement in school, which leads to higher rates of suspension. This helps explain why schools with high levels of security have high rates of suspension. Such schools also have increased racial disparities in their suspension rates, and solutions such as increased security are less effective in addressing student behaviors than evidence-based interventions. The research points to a pattern of subjectivity—that is, how adults perceive and respond to student behavior plays heavily into who gets disciplined and the severity of the consequences.

Teachers and schools must be better equipped to serve all students

The teaching force remains overwhelmingly white. However, since 2014, the majority of public school students have been nonwhite, and public schools continue to serve a growing number of low-income students—who are significantly students of color—as well. As the demographics of classrooms and school buildings continue to evolve, it is important to examine the extent to which race may influence how teachers interpret and respond to students’ behavior and to guard against potential bias. Furthermore, teacher preparation programs, districts, and schools must proactively help teachers recognize and counteract potential biases and develop good relationships with all students.

Some teachers may not think it is their job to discipline students or to use a series of interventions before referring a student to the office. More often, teachers feel that they do not have enough training to work with students effectively. In a 2016 survey, more than half of teachers polled—61 percent—said that they needed more training in teaching’s social and emotional components. More than three quarters—76%—of teachers surveyed by a chapter of Educators for Excellence said that they wanted more training so that they would not contribute to racial disparities in discipline. Properly equipped, teachers can be an effective element in building a positive classroom and school climate.

The path forward

Many education leaders recognize this and have taken steps to address discipline disparities in their communities through a variety of approaches. In Oakland, California, the use of restorative practices has helped to lower discipline referrals and suspensions, thereby narrowing the racial discipline gap. The School District of Philadelphia recently moved to prevent schools from suspending students for nonviolent conduct offenses. Conservative advocates have pointed to the uneven implementation of this approach in order to discourage policymakers from addressing discipline disparities. However, the Philadelphia district’s implementation of discipline reform underscores the importance of providing proper support and training to effectively implement new policies and practices so that they have their intended effect.

To be sure, student behaviors that threaten the safety of others should rightfully incur consequences. At the same time, though, there may be an overreliance on certain forms of discipline that do not increase student safety. That is why it is unconstructive for the Fordham Institute to imply that it is federal overreach to investigate discipline occurrences not just based on individual complaints but also on disparate rates of discipline. Since schools and teachers are not always equipped to serve their students effectively, over time, small everyday practices of educators and school leaders can amount to systemic institutional bias. And racism results from bias in institutional policies, procedures, and practices that favor or disadvantage certain groups of people.

The federal Office of Civil Rights has the responsibility to ensure that racism is not a factor in school discipline policies or the public education system writ large. By issuing its discipline guidance, the Obama administration made clear that it is not acceptable for schools to continue to disproportionately exclude students from the classroom. Asserting its right to investigate based on data and providing tools to proactively address disparate discipline rates is a natural part of the federal government’s role in ensuring equitable and high-quality education for all students.

The status quo is unacceptable, and action from every level of the public school system can support teachers to create positive relationships with all students and effectively and fairly apply discipline when it is warranted. Unless students take extreme, dangerous actions, public schools should not suspend or expel them for misbehavior and deprive them of valuable learning time. Any policy approach will likely come with limitations, but waiting for a perfect policy would leave too much at stake.

Laura Jimenez is the director of standards and accountability for K-12 Education at the Center for American Progress. Abel McDaniels and Sarah Shapiro are research assistants for K-12 Education at the Center.