The Opportunity Zones (OZ) tax incentive has not lived up to its promises of poverty alleviation or economic development. Enacted as part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the incentive initially received little attention.1 Its designers touted it as a “new private sector investment vehicle” for attracting long-term investment into economically distressed areas.2 The incentive provides investors a tax deferral and other tax benefits if they roll over their capital gains—profit made from the sale of a property, stock, or bond—into a qualified opportunity fund which then invests that money into a designated region known as an Opportunity Zone.3 Supporters of the incentive believe that it will unleash a wave of capital into long-impoverished communities, stimulating revitalization via job creation and overall economic growth.4 Almost three years after the passage of the TCJA, however, critics note that it will, by and large, not produce equitable or sustainable economic development for distressed communities.5 They also point out that the incentive is finally being recognized6 for what it truly is: government-sanctioned gentrification7 driven by the capital gains of America’s wealthiest investors. As currently designed, the OZ incentive contains no transparency or reporting structures. Therefore, the public is finding it extremely difficult—if not impossible—to know who raised the capital that is going into OZ-designated areas and where it is being invested as well as who is benefitting from the investments.8

Beyond the OZ incentive, the landscape of past national placemaking efforts begs a long-standing question: Why do federal attempts to tackle economic inequality often fall short of their ambitions? The answer is simple: Despite calls for more equitable economic development, the traditional U.S. placemaking field has largely not come to terms with why many distressed communities—particularly communities of color—became distressed in the first place. Moreover, far too many in the development field do not understand what equity looks like in practice.9 Addressing inequality in economically distressed communities is not simply about deploying more capital to these areas; the capital must also be responsive to the social ills that systemic oppression and disinvestment caused in the first place.

“Placemaking is a multi faceted participative process of planning, design and shared ownership that creates and transforms spaces, neighborhoods, villages, and cities.” – Maria Adebowale-Schwarte, founding director of Living Space Project10

This issue brief explores the equity design flaws of the OZ incentive as well as the allure and elusiveness of equitable economic development. It calls for a transformation of the United States’ approach to placemaking, analyzing why self-determination and self-actualization is integral to community revitalization and how a people- and place-conscious ecosystem can achieve this.

What are distressed communities?

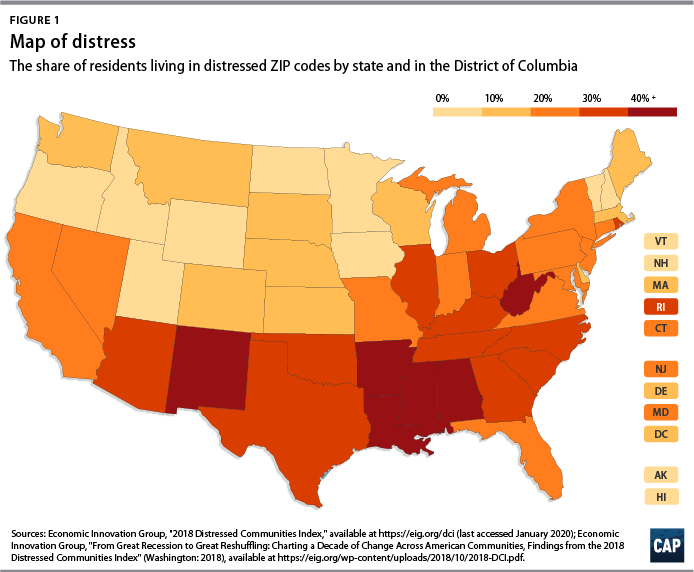

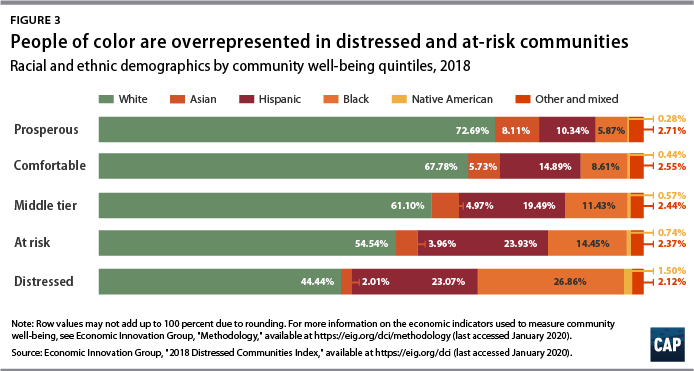

According to recent data, more than 50 million U.S. residents—nearly 1 in every 6—were struggling while living in distressed communities.11 With even more people living in neighborhoods that are at risk of becoming distressed, the economic development field is long overdue for reform that ensures equity is at the core of its objectives, activities, and outcomes. Distressed communities are often defined by higher-than-average population loss, poverty rates, and unemployment rates, as well as inadequate and eroding infrastructure that lacks vital healthy neighborhood features. These communities often have declining local economies due, in part, to loss of businesses and overall economic disinvestment.12 Distressed communities also tend to be overwhelmingly communities of color. Meanwhile, climate change is fueling more extreme weather events that hit economically disadvantaged areas and communities of color the hardest. These communities are often disproportionately exposed to the highest levels of toxic pollution and have the fewest resources to prepare for and recover from climate disasters.13

The persistent distress in these neighborhoods is largely born from a half-century of disinvestment and isolation created by discriminatory policies and practices that effectively cut off, steered away, and withheld public and private investment from these areas. These racialized policies and practices included exclusionary zoning, redlining, slum clearance, urban renewal,14 and racially restrictive covenants, among others.15 Policymakers should have designed OZs to rectify these shameful practices, which provide important lessons regarding past placemaking endeavors that created and exacerbated, rather than alleviated, concentrated poverty and inequality.16

A place-based history lesson in equitable economic development

Although policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels have long given lip service to the idea of centering equity in economic development, they have often lacked the proper framework and commitment to actualize that approach. Equitable economic development promotes the belief that all communities have a right to live in a pollution-free, inclusive, and just economic environment that is free from persistent and systematic discrimination. This can be achieved through comprehensive and community-accountable public action and investment that intentionally dismantles structural barriers and sustainably expands opportunities for all communities—especially communities of color and residents of economically disadvantaged neighborhoods.17

Important tenets of equitable economic development18

- Advance an integrated people, place, and economy approach that centers equity and focuses on the needs of the most disadvantaged

- Account for the inequities that afflict distressed communities and their residents

- Embody a community-responsive development framework grounded in economic, racial, and environmental justice principles

- Prioritize community self-determination through meaningful local participation, leadership, ownership, and control

- Invest in and strengthen local ecosystems, community capacity, and assets via anchor institutions, public infrastructure, and initiatives

- Incorporate a robust reporting and evaluation framework that identifies, tracks, and measures community benefits and equity outcomes

Historically,19 national place-based initiatives depended upon federal spending and control to bring about the responsible development and revitalization of housing, infrastructure, and main streets in disinvested communities. However, over time, the role of federal, state, and local governments has diminished, resulting in less capacity to direct resources to where they are needed most. Since the 1980s, community development has followed a neoliberal approach, conforming to market rules and limiting government involvement.20 As such, federal, state, and local governments have increasingly relied on tax cuts and tax credit policies to incentivize the private sector to carry out the national public good agenda—a responsibility that the private sector is, on the whole, ill-suited and disinclined to carry out.

The closest the federal government has come to some semblance of equitable place-based development were Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson’s Community Action Program—part of the War on Poverty—and President Barack Obama’s suite of neighborhood revitalization initiatives, including Promise Neighborhoods, Choice Neighborhoods, and Promise Zones.21 Each of these efforts centered a community-led, interdisciplinary, integrated, and place-conscious approach instead of one that was top-down and outsider-driven.22 Like the place-based anti-poverty field, the Kennedy, Johnson, and Obama administrations acknowledged that while a lack of access to capital is a major contributor to the already massive and growing socioeconomic inequality in long-distressed communities, it is not the only factor.23

Unfortunately, the OZ incentive is proving to be just the latest iteration of post-1960s federally backed placemaking, as it was not designed to confront the systemic inequities that created distress and concentrated poverty in disinvested communities.24 To change this, the United States must adopt a placemaking approach that follows and supports distressed communities’ self-determined visions and blueprints for economic, social, and environmental well-being.

Equitable economic development fundamentally necessitates both a people- and place-conscious framework that refuses to separate distressed places from the people who have long resided in them. This demands a fundamental change in how community development stakeholders value long-distressed communities and the residents who live there, as more often than not the relationship between communities and stakeholders has been plagued by predatory, paternalistic, and extractive behaviors.

Opportunity deferred: Examining the design flaws of the OZ incentive

Proponents of the OZ incentive continue to herald it as a poverty alleviation tool designed to funnel private capital into low-income census tracts that were nominated by governors in every U.S. state and territory as well as the mayor of Washington, D.C.25 Given that 19 million people who are economically insecure—defined as living at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty line—live in OZs, the incentive, if properly structured, could transform low-income communities across the nation.26 However, the incentive’s design largely ignores the needs of these low-income communities in favor of clearly defined tax benefits for wealthy investors chasing the highest rate of return.

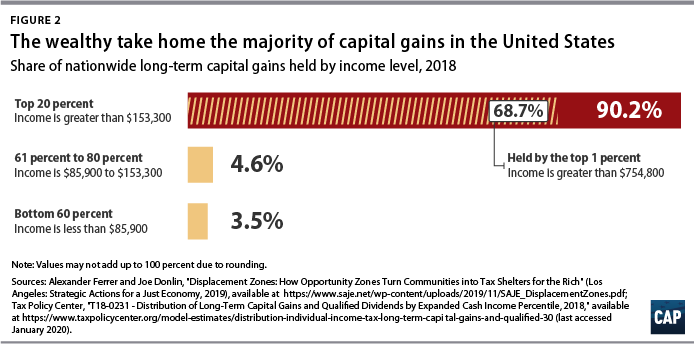

First, the target demographic for the OZ incentive is quite exclusive. According to The New York Times, only 7 percent of Americans report taxable capital gains on their tax returns, and almost two-thirds of that income was reported by individuals with a total annual income of $1 million or more.27

Second, the OZ incentive drives investors to seek projects with high rates of return—such as high-end real estate—rather than projects that these areas critically need such as supermarkets, affordable housing, community health centers, clean energy, resiliency measures, and accessible transportation options.28 Third, the OZ incentive does not feature performance metrics to measure its success. It provides no guidance on how investments should create jobs and business opportunities for existing residents, protect existing residents from displacement, or reduce poverty or the racial wealth gap.29 It also does not provide guidance on building new community infrastructure that would allow for greater socioeconomic mobility. Failure to tie the OZ tax break to these types of performance measures will mean that its benefits for existing residents are not guaranteed. Finally, the structure of the OZ incentive was not designed to support the neighborhood revitalization activities of community development financial institutions (CDFIs) and other organizations that have a demonstrated history of investing in economically distressed communities.30

Second, the OZ incentive drives investors to seek projects with high rates of return—such as high-end real estate—rather than projects that these areas critically need such as supermarkets, affordable housing, community health centers, clean energy, resiliency measures, and accessible transportation options.28 Third, the OZ incentive does not feature performance metrics to measure its success. It provides no guidance on how investments should create jobs and business opportunities for existing residents, protect existing residents from displacement, or reduce poverty or the racial wealth gap.29 It also does not provide guidance on building new community infrastructure that would allow for greater socioeconomic mobility. Failure to tie the OZ tax break to these types of performance measures will mean that its benefits for existing residents are not guaranteed. Finally, the structure of the OZ incentive was not designed to support the neighborhood revitalization activities of community development financial institutions (CDFIs) and other organizations that have a demonstrated history of investing in economically distressed communities.30

By design, the OZ tax incentive will mostly benefit wealthy investors. Rather than helping distressed communities, these investors are on a path to harm them, as investors are incentivized to support gentrification and the displacement of current residents. This is particularly alarming considering the devastating impacts of increasingly extreme weather events and the heavy concentration of pollution sources in economically disadvantaged areas. The OZ incentive was not designed to promote investments in projects that help reduce local pollution or build future-ready, resilient infrastructure and housing that can withstand more extreme heat, storms, floods, and other climate change effects.31 In short, OZs as they are currently designed will solidify already entrenched inequities rather than serve as a tool for community wealth-building.

Bamboozled, hoodwinked, and led astray: Seduced by the promise of OZs

Press coverage about the implementation of the OZ incentive has been polarized.32 President Donald Trump has supported the incentive, stating, “We’re providing massive tax incentives for private investment in these areas to create jobs and opportunities where they are needed the most.”33 However, The New York Times’ Editorial Board slammed OZs, writing, “Of all the ways President Trump’s 2017 tax cut has enriched the wealthy at the expense of the public interest, perhaps the most outrageous is the black comedy of ‘opportunity zones.’”34

From a policy perspective, the stark contrast in opinions on OZs is telling. The lack of transparency and objective data collection around the OZ incentive has meant that one’s view of it is mostly driven by what information one has access to as well as that information’s source.35 Policymakers have largely been forced to evaluate the massive public subsidy of the OZ incentive through anecdotal evidence from around the country. This is unacceptable. Policymakers should have access to sound empirical data collected by the federal government, and those data should be shared publicly.36

The U.S. Department of the Treasury recently made an effort to provide an avenue to track the effects of OZ investments.37 However, the incentive is on the same path as past federal efforts that relied on tax incentives to spur economic development within historically disadvantaged communities—and that failed to demonstrate proof of concept.38

Equitable economic development requires more than access to capital

As Kelly Price crooned in the Notorious B.I.G.’s “Mo Money, Mo Problems,” “It’s like the more money we come across, the more problems we see.”39 Simply infusing capital into distressed communities does not address the systemic inequities that discriminatory policies and the actions of both public and private entities created. As a result, initiatives such as OZs often create or exacerbate problems for longtime residents of disinvested communities in the form of outsider land grabs that spur new or fuel existing gentrification and displacement.40 This is because these initiatives were not designed with the supports and access points that would have allowed communities to meaningfully take part in their own revitalization.

The type of money utilized in economic development is just as important as how it is deployed, as this determines who has the access and power to dictate what is developed. (see Figure 2) Again, to assume that capital is the be-all and end-all is to ignore the necessity of enabling distressed communities to determine their revitalization, build their capacity, and recognize and invest in their assets—a core, nonnegotiable tenet of equitable economic development. As Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) often says, “The people closest to the pain should be closest to the power.”41 The residents of disinvested communities are the foremost experts on their own lives and surroundings and thus know best the solutions needed to sustainably better their neighborhoods. Yet, as history has demonstrated,42 access to the power, resources, and opportunities to effect local solutions and self-determined prosperity has almost always been discriminately withheld,43 sabotaged,44 or obliterated.45

“I don’t think we should ignore the historical conditions that led to disinvestment in these communities—particularly [the] concentration of poverty really driven by racism and discrimination in many of these places. And while voluntary frameworks are useful for those actors who want to do the right thing … we know capital doesn’t flow to these places not because these places aren’t worth investing [in], not because there aren’t good ideas or smart people or growing businesses. It’s because the market doesn’t value these places, and this incentive creates an opportunity. But without something further to nudge a market in the direction, I fear personally that what we’re going to do is reinforce those stereotypes that exist in the way that capital flows currently. And I don’t see any mechanism where we sit today to address any of that inequity, particularly racial inequity in a lot of these places.”46 – Aaron Seybert, managing director of the Social Investment Practice at the Kresge Foundation,47 testifying before the House Subcommittee on Economic Growth, Tax, and Capital Access during a hearing titled, “Can Opportunity Zones Address Concerns in the Small Business Economy?”

Furthermore, the notion that any type of capital will suffice is not only a myopic approach to revitalization but also a particularly ill-informed and caustic one when applied to communities of color that have long been left behind. The ongoing devastation created by racist subprime lending and real estate practices of the U.S. housing industry proves that the type of capital—both financial and social—matters just as much as who has access to it.48 Consequently, this approach never confronts the long-standing policies and practices that made these communities of color distressed in the first place, nor does it address the racialized ideology around so-called risk that was created more than a century ago and still dominates the lending and investment industries.49 As the Kirwan Institute observed in its report, “Challenging Race as a Risk”:

The ability to exercise agency over where one lives is a hallmark of freedom. And yet, this privilege has not been equally afforded to all. Race has been—and continues to be—a potent force in the distribution of opportunity in American society. Despite decades of civil rights successes and fair housing activism, who gets access to housing and credit, on what terms, and where, remains driven by race.50

Equitable economic development policies require a comprehensive and intersectional justice framework

“Persistent racial and economic inequalities—and the forces that cause them—embedded throughout our society have concentrated toxic polluters near and within communities of color, tribal communities, and low-income communities.”51 – The Equitable and Just National Climate Platform

Historically, communities of color have often been denied equitable access to the opportunities and resources needed to build and sustain thriving neighborhoods.52 The persistent racial and economic inequalities within the United States have created greater environmental and public health risks for low-income and tribal communities as well as communities of color, directly contributing to the climate crisis that currently grips the planet.53 Communities of color have had their neighborhoods stolen,54 segregated,55 degraded,56 preyed upon,57 displaced,58 polluted,59 and even destroyed.60 Given this history, equitable economic development policies must not only be rooted in racial and environmental justice but must also be developed and implemented by the individual communities they are meant to help.

As leading scholar of critical race theory Kimberlé Crenshaw has stated, “If we can’t see a problem, we can’t fix a problem.”61 Until policymakers acknowledge that placemaking has always been political and continues to be profoundly racialized—as a place is inextricably tied to its residents—the community development field is doomed to repeat the same lackluster and harmful approaches that neither revitalize communities nor alleviate inequity.62 The place-based investment challenge that has always been before the United States is whether such investment can sustainably bring about equitable economic development that prioritizes the needs and leadership of the communities most harmed and held back by inequitable policies and actions. There is also the long-standing question of whether the willpower, humility, and courage exist to actualize this development.

Equitable economic development promotes a thriving people- and place-conscious ecosystem

“Our vision is that all people and all communities have the right to breathe clean air, live free of dangerous levels of toxic pollution, access healthy food, and enjoy the benefits of a prosperous and vibrant clean economy.”63 – The Equitable and Just National Climate Platform

In nature, an ecosystem is a diverse self-producing system of living and nonliving things that dynamically interact in balance with one another and their physical environment.64 The primary function of an ecosystem is to form, nurture, and sustain healthy, diverse life forms.65 Similarly, when it comes to equitable community development,66 a thriving people- and place-conscious ecosystem is one in which people and the social, economic, and environmental conditions and assets where they reside interact to produce the resources, opportunities, and access necessary for all community members to form healthy, thriving, and sustainable neighborhoods. Such neighborhoods are prepared for the extreme weather events caused by climate change.

Communities are actively shaped by their societal, economic, and environmental contexts; they are important parts of geographic regions and key pillars of the broader social ecosystem.67 A people- and place-conscious ecosystem reflects the fact that a place cannot be divorced from the people who reside there and ensures that longtime residents are not displaced once their area begins to receive the attention and resources it was long denied. This model also acknowledges and prioritizes a system that has often been overlooked and resource-constrained: the existing and locally rooted community development finance system, which has long delivered capital to distressed, low-income, and other under-resourced communities. Simply put, to create people- and place-conscious ecosystems, place-based approaches must invest in both redressing the harms of disinvestment and cultivating sustainable future-ready revitalization and shared prosperity. Placemakers can do so by utilizing the rich community assets and finance system already in place as well as reinforcing the statutes that bolster them such as the Community Reinvestment Act and New Markets Tax Credit Program.68

“I see real community development as combining material development with the development of people. Real development, as I understand it, necessarily involves increasing a community’s capacity for taking control of its own development—building within the community critical thinking and planning abilities, as well as concrete skills, so that development projects and planning processes can be replicated by community members in the future.”69 – Marie Kennedy, professor emerita in community planning at the University of Massachusetts Boston

Done correctly, this form of placemaking will maximize existing community assets, prioritize shared values, and cultivate a local economy that organically and sustainably supports thriving environments and healthier lives. In contrast, places of concentrated poverty, distress, and environmental injustice are not “natural” but rather the product of inequitable public and private policies and practices.70 In essence, distressed communities can be identified by a host of social, economic, and environmental indicators that together reflect the extent to which families are forced to look beyond their immediate communities to access essential infrastructure, resources, and opportunities, as well as private and public services needed to thrive.71 These can include quality schools, housing, health clinics, grocery stores, gainful employment with family-sustaining wages, and clean and climate-resilient infrastructure. For example, due to systemic discrimination and neglect,72 far too many Baltimore communities suffer from preventable deadly health issues linked to heat pollution due to a lack of green spaces and subpar neighborhood design.73

Overcoming past policy harms will require the mobilization of U.S. assets to invest in the creation of equitable communities, especially in the face of devastating climate impacts that will disproportionally affect low-income communities and communities of color.74 These government assets include but are not limited to direct investment via grants, low-interest loans, technical assistance, governance, and oversight supports. As the historic Equitable and Just National Climate Platform—signed by more than 220 environmental justice and local and national environmental organizations—states, “Generations of economic and social injustice have put communities on the frontlines of climate change effects.”75

Disrupting and reversing the trend of persistent, place-based poverty and distress requires a multilevel engagement of diverse stakeholders, investments, and approaches. It also requires a nuanced understanding of utilizing the right capital tool to address community-identified needs. As such, interventions must consistently be developed in partnership with communities and in accordance with their defined needs and priorities. Building this type of ecosystem will require a complete reimagining and reprioritizing of how federal, state, and local governments—as well as the community development landscape writ large—views, values, and interacts with disinvested communities.

Essential equitable economic development actors

Driven by a social mission to create change in the same way that for-profit organizations need to produce revenue, nonprofit actors such as community development corporations (CDCs) and other intermediaries, CDFIs, community land trusts, and foundations have and will continue to play key roles in the evolution of strategies for tackling persistent poverty and disinvestment in distressed neighborhoods.76 In 1997, Harold Mitchell—a resident of Spartanburg, South Carolina, who went on to serve in the state’s House of Representatives from 2005 to 2017— founded ReGenesis, a certified CDC focused on cleaning up contaminated and abandoned property in Spartanburg.77 Serving as a critical representative of neighborhood interests, ReGenesis worked with local government and environmental agencies to assess levels of contamination and develop a plan to address the environmental harms plaguing these communities.78 Starting in 2000, ReGenesis began to focus on equitable neighborhood revitalization work, driven by its ability to build and sustain new partnerships. By leveraging a $20,000 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency environmental justice small grant into more than $300 million in public and private funding, ReGenesis was able to launch an ambitious, community-driven approach to neighborhood reinvestment.79 Over the past 20 years, ReGenesis has brought job training programs, 500 affordable housing units, six health clinics, clean energy, and other critical community elements to Spartanburg.80

Unlike the OZ incentive, CDFIs and other foundations have long recognized the importance of providing varied yet locally accessible forms of capital and technical capacity assistance as well as connecting diverse stakeholders to help sustain and strengthen community-building initiatives. These entities often serve as the connective tissue between specific community needs and generalized local, state, and federal policies and programs. Locally rooted organizations involved in community development finance are leading meaningful innovation that utilizes and effectively deploys capital tools that serve multiple interests. That said, they are not a substitute for the role of federal, state, and local governments, which must recommit to and ramp up their appropriating, oversight, and cross-sector aligning functions in order for equitable and accountable community-building to be sustainably realized.81

While each stakeholder in the community development space has a critical role to play, at its core, the goal of a thriving people- and place-conscious ecosystem is self-determination. This includes control over local assets and development decisions as well as the resources, tools, and supports that come with it.82 Black, Native, and Latinx communities in particular have the least amount of power and resources when compared with white communities, who have historically had more resources and exercised greater control over the fates of their neighborhoods.

Equitable economic development requires that communities be free to set the conditions that allow their placemaking vision to be realized and sustained, especially when outside capital and the private sector are involved. What this mandates, in part, is a continual process of rectifying both past and present inequitable structures that govern the community-building space while at the same time constructing a new placemaking infrastructure and approach that acknowledges and defers to the agency and power that distressed and disinvested communities have possessed all along.

Equitable economic development requires that communities be free to set the conditions that allow their placemaking vision to be realized and sustained, especially when outside capital and the private sector are involved. What this mandates, in part, is a continual process of rectifying both past and present inequitable structures that govern the community-building space while at the same time constructing a new placemaking infrastructure and approach that acknowledges and defers to the agency and power that distressed and disinvested communities have possessed all along.

Conclusion

“Place defines who we are as individuals and as a society who we are or what we want, as much as our social networks and political beliefs. And the places we provide for people to live in are a measure of how much we respect human rights, fair economics and the environment.”83 – Maria Adebowale-Schwarte, founding director of Living Space Project

Reforming the United States’ placemaking investment framework is no easy feat, but it is long overdue and well worth the endeavor for the sake of equity. Achieving equitable, climate-ready economic development will require a complete rethinking of national and local frameworks. To start, U.S. placemakers must be intentional about redressing both current and past initiatives that continue to produce inequitable outcomes based on race, socioeconomic status, and geography. The persistence of people living in neglected places plagued with extreme, concentrated poverty and pollution is a political choice often dictated by a powerful few. This choice can and must be undone.84

OZs as currently designed fail as an equitable economic development tool and thus must be completely overhauled or fully repealed. This nation’s prosperity and strength are measured by the health and well-being of its people and environments. Moving forward, U.S. placemakers—from policy to practice—must embrace a framework for a people- and place-conscious ecosystem through which distressed communities can achieve the self-actualized health and well-being that they need and deserve.

Rejane Frederick is the associate director for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress. Guillermo Ortiz is a former research associate for Energy and Environment at the Center.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Olugbenga Ajilore, Cathleen Kelly, Trevor Higgins, Aaron Seybert, Brett Theodos, Alexandra Cawthorne Gaines, Taryn Williams, Ben Olinsky, Michela Zonta, Danyelle Solomon, Winnie Stachelberg, Sarah Figgatt, Julia Cusick, Claire Moser, Sally Hardin, Jaboa Lake, David Ballard, Christine Sloane, Krista Jahnke, and the CAP Art and Editorial team for their review and contributions.