For the first time, the federal government has published data on the outcomes of students who begin their college career studying part-time. The data are clear: American higher education needs to do a better job helping these students get through college. Just less than 25 percent of part-time students receive a degree or certificate within eight years from the college where they first enrolled.

Even though 37 percent of college students are attending on a part-time basis,* they have been ignored by federal graduation rates until now. Traditional rates only track new students who start their college careers with a full-time course load, leaving out those who start by enrolling in fewer credits, take time away from school, or transfer.

Other data sources have illustrated that part-time students face dismal odds of ever making it to graduation. But until now, we have not been able to delve into how part-time students fare at individual institutions, which has made it much more difficult to figure out what kinds of policies and supports would be most effective in helping them succeed.

The new Outcome Measures (OM) cover about 1.2 million part-time students who started college for the first time in 2008 or who entered a new institution as transfer students in the same year. Although there are limitations to these data, the OM represent a major accomplishment of the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics, providing additional information on a group of students that is too often invisible to decision-makers.

Part-time students: Hidden in plain sight

In “Hidden in Plain Sight: Understanding Part-Time College Students in America,” the Center for American Progress recently called for policymakers, institutional leaders, and researchers to put part-time students at the center of their work on how to improve national postsecondary attainment rates. CAP’s research showed that the lives of part-time students are often much more complicated than those of traditional, full-time students. Most part-time students are more than 24 years old and supporting themselves financially. About three-quarters of them are working, and 42 percent work at least 40 hours per week. Nearly 4 in 10 are caring for dependents. These circumstances all make it more challenging to stay enrolled and complete a credential, so decision-makers need to think more creatively about how to serve these students.

Thanks to the new OM, there is now some important, if limited, information to help them do so.

New data improve on traditional graduation rates

Traditional graduation rates, created in 1990, were originally conceived by lawmakers concerned about the outcomes of student athletes. In counting only first-time, full-time students, they leave out more than 50 percent of entering undergraduates and two-thirds of students at community colleges.

This presents several problems. Policymakers hungry to hold colleges accountable for their students’ outcomes lack appropriate, comparable data on which to base measures. Students planning to enroll part time cannot get a good idea of how much time it may take to complete their program or which college will serve them best. And institutions lack a benchmark for their own performance in retaining part-time students.

The new Outcome Measures fill several gaps in our knowledge. They report each school’s outcomes separately for students who were part-time and full-time in their entering semester, as well as distinguish between both part-time and full-time students who were in college for the first time when they started and those who had previously attended college elsewhere.

The OM therefore create four student groups for which outcomes are collected. They report how many students have earned a degree or credential—anything from a one-year certificate to a bachelor’s degree—within six years and eight years of entering a particular college. They also show how many students remain actively enrolled and how many have transferred to a different institution within the past eight years.

Unfortunately, we are only seeing a small slice of part-time students reflected in these data—those who were attending part-time when they first entered a college. Although most students start college as full-time enrollees, more than half eventually attend part-time for some portion of their college career. Students with this type of mixed enrollment intensity are difficult to track due to limitations of federal data collections. This issue could be resolved with a national student-level data network, but Congress banned the creation of one in 2008. Still, these data provide invaluable insight into how part-time and transfer students fare at individual colleges, providing better information that institutions can use to improve policies for these students.

A snapshot of part-time students’ outcomes

Only 18 percent of part-time, first-time students received any kind of credential—including a certificate—within eight years at the institution where they started. Another 31 percent of part-time, first-time students transferred to another institution or remained enrolled at the original institution eight years later. (see Figure 1) The data do not reveal whether those who transferred obtained a degree at their next institution.

The story is not quite as grim—although still troubling—for part-time transfer students, 29 percent of whom received some credential within eight years of entering their transfer institution. One-third went on to attend elsewhere or remained enrolled, highlighting just how long it can take part-time students to finish a degree.

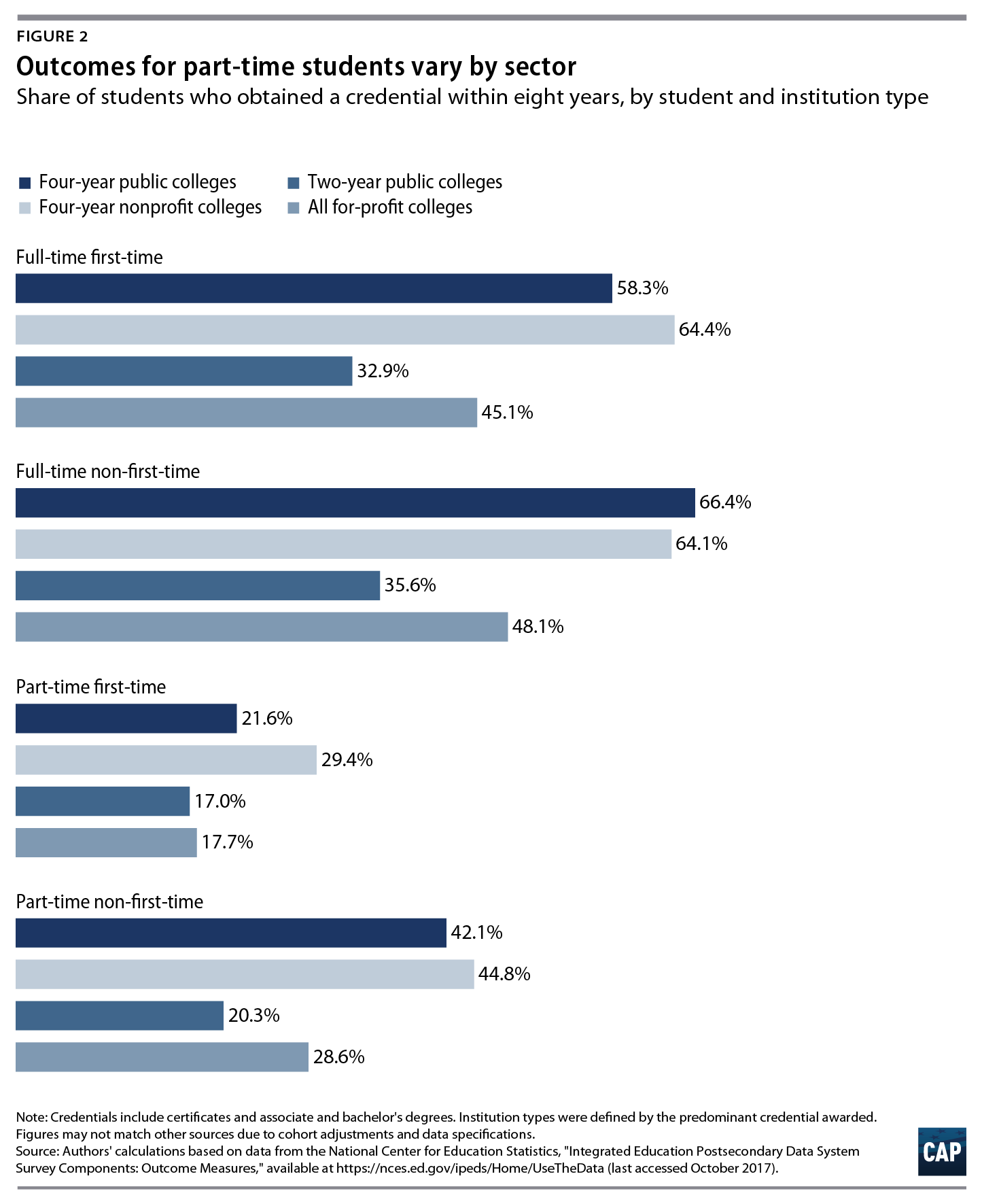

We see significant variation in attainment rates by sector. (see Figure 2) Two-year public colleges have the lowest attainment rates overall, though their rates for part-time, first-time students are nearly the same as those of students in the for-profit sector. For-profit colleges likely do better because they specialize in short-term credentials below the level of an associate degree.

Transfer students—especially part-time transfer students—are almost always more likely to obtain a credential than their first-time peers, likely in part because they have accumulated credits at their previous institution. They also may be more likely than first-time students to have figured out how to succeed in college or to have decided what they want to get out of their education.

The attainment rates of four-year public and private nonprofit institutions are similar, while public two-year colleges fall behind when it comes to getting both full-time and part-time students across the finish line. This does not mean that community colleges are not graduating students. While public two-year and for-profit two-year and four-year colleges have nearly the same number of full-time completers, community colleges have more than three times as many part-time completers. (see Table 1) In fact, two-year public colleges account for 45 percent of part-time credential earners, a testament to the sheer size of the sector.

The lower rates of attainment at community colleges may be attributable in part to the large number of students who transfer rather than graduate, which is part of the mission of these institutions. Figure 3 shows that public two-year institutions have the highest rates of students who are still enrolled at their original college or who enrolled at another institution within eight years of first entering a college. For each sector, more than 90 percent of these students are those who transferred. Again, the data do not indicate whether those students graduated or not—they only show that they enrolled.

Therein lies the paradox of the Outcome Measures. They provide much more information than traditional graduation rates, but they offer only the broadest of brushstrokes to aid understanding of how students’ outcomes differ across groups.

The measures show how many students completed but not their credential type. They show how many transferred but not whether they finished their degree. They show whether students were part-time or full-time when they entered but not whether those students spent the bulk of their college career with part-time or full-time status.

Many leaders of institutions will be grateful for the OM because they can use this new resource to show that their schools accomplish more than they are given credit for under traditional graduation rates.

It is very important, however, for institutions to go beyond using the data in flattering talking points. Institution leaders need to look hard at how their part-time students fare compared with those at peer institutions—and ask how their schools can do better.

* Author’s analysis of U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) (2015), fall enrollment. See the data here.

Colleen Campbell is the associate director for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress. Marcella Bombardieri is a senior policy analyst of Postsecondary Education at the Center.