Introduction and summary

The continent of Africa is enormously diverse. Africa includes 54 countries and more than 1.2 billion people.1 According to U.N. estimates, Africa may hold up to a third of the world’s entire population by 2100.2 Africa encompasses a remarkable range of geography, language, culture, economies, and political organization.

Yet, incredibly, the United States is at a moment where some of its most senior government leaders seem to question the value of engaging on the continent in a significant and forward-looking fashion. The notion that the United States would offhandedly dismiss the importance of an entire continent should be absurd on its face, and it would be easy to write off the current posture as simply reflecting the worldview of President Donald Trump as an individual. However, the U.S. view toward Africa is more deeply embedded than President Trump.

Unfortunately, few Americans consider Africa and think about important long-term opportunities for the United States. Instead, the media and even some U.S. policymakers have all too often used the language of threat when discussing Africa, creating an oversimplified and distorted vision of the continent. Even when making the case for engaging Africa, commentators, government officials, and nongovernmental organizations have leaned heavily on issues such as refugees, infectious diseases, famine, and a general portrait of misery to make the case for U.S. involvement.

The reality is that Africa is home to some of the fastest growing markets in the world, and its potential as a dynamic future export market for U.S. goods and services is enormous.3 Around 1.5 percent of total U.S. exports are currently destined for sub-Saharan Africa, underscoring how much room for growth there is over the long term.4 In short, the United States stands to significantly benefit from growing trade and lasting alliances in Africa if it positions itself strategically today.

The United States needs to make some key investments and policy choices now to seize this opportunity. First and foremost, the United States should immediately move to staff key positions at the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) related to Africa.

In addition, the administration and Congress should:

- Encourage greater economic integration across Africa—not just through trade agreements—but also by assistance and diplomacy designed to cut transport times and reduce other nontariff obstacles to goods, services, and people moving more freely on the continent

- Renew their commitment to democracy and the rule of law at a time when Africa is demonstrating important, but uneven, progress

- Redouble efforts to make the Power Africa initiative a success

Importantly, all of these steps not only serve Africa well, they also advance U.S. interests on a continent that is more stable, prosperous, and democratic. Until and unless the narrative shifts, and America begins viewing Africa as a place where opportunities—not just threats—exist, the United States will continue to do a grave disservice to its own interests and those of the many African nations with the potential to serve as increasingly important allies, trading partners, and sources of lively and entrepreneurial social innovation and exchange. At a time when China and Europe are also fiercely competing to engage in Africa, it is vital that the United States find itself on the right side of history by standing with those on the continent embracing free governments and markets.

A record of relative neglect

While Africa has always struggled to break through the periphery of the broad U.S. conversation about international security, economics, and interchange, the situation has been exceedingly grim under the Trump administration. Sixteen months in, the Trump administration has no assistant secretary for Africa at the State Department—the top diplomatic position dealing with the region in the U.S. government. While the administration has recently put forward a nominee for this role,5 key U.S. ambassadorial appointments in South Africa, Tanzania, Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Nigeria, have yet to be moved forward.6 Moreover, the Trump administration has also decided to leave the special envoy position for Sudan and South Sudan vacant.7 Finally, the senior political positions at USAID dealing with development in Africa are also lacking appointments at this juncture.8

The administration’s tone was set quite early on by a series of snubs of important African officials. No senior administration official was made available to meet with Rwandan President Paul Kagame when he visited the United States in March 2017.9 In April 2017, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson invited African Union Commissioner Moussa Faki to Washington, D.C., then backed out of the meeting for no apparent reason and only notified Faki of that fact at the last minute.10

Additionally, the administration has repeatedly targeted the foreign assistance program for cuts of up to 30 percent, and the impact of these cuts would be felt disproportionately in Africa on a whole range of issues as about a third of USAID funding is spent on programs on the continent.11 The initial Trump budget request also called for zeroing out a number of important efforts, such as the Famine Early Warning System, that have been relatively low cost but very effective in preventing crises on the continent.12 The administration also suspended support for the United Nations Population Fund, a particular concern because of the unmet need for contraception and family planning.13 The importance of democracy and the rule of law has also been consistently downplayed by administration officials, and that has surely not gone unnoticed in Africa at a time when it is making steady efforts to consolidate free governance.

Making matters worse, in September 2017, President Trump twice referred to the nonexistent country of “Nambia” during a speech at the United Nations to a group of Africa leaders.14 (Trump apparently meant “Namibia,” a fairly innocuous gaffe under most circumstances, but it did little to improve the state of relations.) Another Trump statement from the same set of remarks had oddly colonial undertones: “I have so many friends going to your countries, trying to get rich. I congratulate you. They’re spending a lot of money.”15

That same month, Chad—a key U.S. ally in combatting terrorism in the Sahel region—was placed on the administration’s travel ban list.16 This move appears to have come about literally because of shortage of the proper paper for processing passports and visas.17 While the country has since been taken off the travel ban list, the fact that a key counterterrorism partner was added to the travel ban, even temporarily, over a dispute about office supplies further fueled perceptions that the administration neither cared about, nor understood, the continent.

Then, in January 2018, Trump made perhaps his most serious misstep with regards to Africa when, in a White House discussion with lawmakers from both parties on immigration, he referred to African countries saying—”Why are we having all these people from shithole countries come here?”18 During the same discussion, he reportedly stated his preference for immigrants from Norway and Asia, viewing them as of more value to the United States. Trump’s comments reverberated widely in the United states and abroad. Spokesperson for the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Rupert Colville argued, “There is no other word one can use but ‘racist’… [More than just] vulgar language … It’s about opening the door to humanity’s worst side, about validating and encouraging racism and xenophobia.”19

Even the administration’s attempts at damage control seemed to backfire. In March 2018, Secretary Tillerson made his first visit to Africa, 14 months into his term. The trip appeared to get off to a good initial start, as the State Department tried to focus on key issues such as development, counterterrorism, and good governance. However, a couple of days into the six-day trip, the visit became increasingly disastrous, with Tillerson cancelling activities and cutting the trip short after being fired by President Trump, sending a clear message that the president did not view the trip as of being of particular significance.20

As Pat Utomi, professor of political economy at Lagos Business School, noted, “American foreign policy has always treated Africa as a leftover, which is why it’s not a huge shock that Tillerson was in Africa while they fired him.”21 He went on to say, “It doesn’t augur well for the long-term message of America to Africa, especially with the message he sounded, which was ‘beware of China.’ This means that the warning he was giving was of no consequence.” 22

In terms of policy approaches, to date under President Trump, the U.S. government appears much more focused on engaging on the continent militarily than in investing in diplomacy and development or exploring how best to maximize long-term economic engagement through trade.23 In the aftermath of the October 2017 ambush in Niger in which four U.S. soldiers were killed, Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis told the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee that the military would be focusing more on Africa as part of its counterterrorism strategy.24 However, according to recent reports, Secretary Mattis has ordered a review of American Special Operations forces, which could result in cuts to counterterrorism forces in Africa as the Pentagon shifts its focus to the growing threats posed by Russia and China.25

The Africa narrative that views the continent as a place exclusively of fear, danger, and desperation doesn’t just emanate from Trump—although he does it with a larger megaphone than anyone else.

To its credit, in April, the Trump administration signed bipartisan legislation—the African Growth and Opportunity Act and Millennium Challenge Act Modernization Act—which renewed some key trade preferences for Africa.26 The African Growth and Opportunity Act, often simply known as AGOA, has been a key foundation for trade with Africa since it was originally passed in 2000.27

AGOA provides U.S. trade preferences to African states that are moving toward market economies, avoiding serious human rights abuses, and that are not undermining fundamental U.S. security interests. More than three dozen countries now receive preferences through AGOA,28 and as the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative notes, “nearly all (97.5 percent) of products from eligible sub-Saharan African countries that meet certain basic eligibility criteria” are now given such preferences.29 Countries graduate out of AGOA preferences if they hit a certain income level. However, as recent experience has made clear, it is time for the U.S.-Africa trade relationship to move far beyond AGOA given some of its limits, which are discussed below.

The positive case for engagement on the continent

Since World War II, every president—except the current one—has fundamentally understood that expanding the global pool of free market democracies is in America’s best interests because doing so helps produce reliable allies, good trading partners, and represents a solid bulwark against conflict and extremist ideologies. While that realization has often played out very unevenly in how different administrations have approached Africa, it is difficult to look at the continent at this moment and not see the enormous potential upside of more intensive and enlightened U.S. economic, political, cultural, and social engagement moving forward.

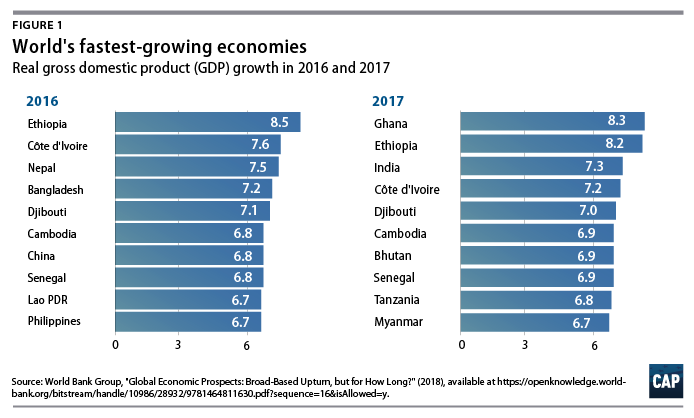

According to data from the World Bank on 2017 gross domestic product (GDP) growth estimates, 4 of the 10 ten fastest growing economies in the world were in Africa—Ethiopia, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, and Senegal. Forecasts for 2018 are even better, with 6 of the top 10 fastest growing economies in Africa—Ghana, Ethiopia, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Senegal, and Tanzania.30 The World Bank also forecasts that overall GDP growth in sub-Saharan Africa will be at 3.2 percent in 2018, up from 2.4 percent in 2017.31 In their report, “Doing Business 2018: Reforming to Create Jobs,” the World Bank also found that sub-Saharan Africa again had the highest number of reforms to business regulations and the highest regional score increase, all of which reduced the global cost of doing business in 2017.32

The United Nations projects that more than half of global population growth until 2050 is expected to occur in Africa, resulting in a doubling of the population—from about 1.3 billion to 2.5 billion.33 This growth will also mean that Africa’s share of the global population, which is currently around 17 percent, will increase to around 26 percent by 2050. This has enormous implications for Africa’s potential as an export market. This comes at a time when Africa’s middle class is growing substantially, particularly in urban areas, and will grow to more than a billion consumers.34 For instance, according to statistics from the U.S. Trade Representative, the number of African households with discretionary spending roughly doubled between 2000 and 2012; real dollar consuming spending nearly doubled from $356 billion in 1990 to $680 billion in 2008; and Africa’s urban population is now larger than the combined urban populations of North America and Europe.35

As The Economist notes:

Africa’s 1.2 billion people also hold plenty of promise. They are young: south of the Sahara, their median age is below 25 everywhere except in South Africa. They are better educated than ever before: literacy rates among the young now exceed 70% everywhere other than in a band of desert countries across the Sahara. They are richer: in sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion of people living on less than $1.90 a day fell from 56% in 1990 to 35% in 2015, according to the World Bank. And diseases that have ravaged life expectancy and productivity are being defeated—gradually for HIV and AIDS, but spectacularly for malaria. Some of the gains may seem modest, but given that living standards across Africa declined during the 30 years after independence they are sufficiently established to prove lasting.36

In March 2018, leaders of 44 African nations signed the African Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) agreement,37 establishing the free flow of goods and services between member states and removing trade barriers, such as a 90 percent reduction in trade tariffs.38 Following ratification processes in each of the member states, the agreement will come into force. And while some of the continent’s largest economies, including South Africa and Nigeria, have not yet signed on to the CFTA, it is still a landmark agreement—the largest since the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995—which has the potential to greatly boost trade, economic growth, and employment.

In addition, a number of subregional trading communities are in place across the continent—such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), among others. These subregional communities often have more political and economic salience for their respective member states than the CFTA, which is in its earliest stages. However, one motivation for creating the CFTA was to address inefficiencies created by having multiple overlapping regional economic communities.39

Africa has also been home to some important steps forward in innovation, with the use of technology allowing for a quantum leap in everything from health care to the economy. In 2000, only about 1 percent of Africans had phone connections. Today, more than 50 percent of Africans have mobile phones, and that number continues to rise rapidly.40 The number of Africans online has also climbed, growing from 53.62 million users on the continent in 2010 to 190.1 million users in 2016.41 However, as noted by The World Bank in their 2016 report on digital dividends, access to digital technologies is not evenly distributed.42 For instance, across the continent, according to the report, women are “less likely than men to use or own digital technologies,” and there are even larger gaps between older and younger populations.43 Additionally, the percentage of individuals with internet access in the wealthiest 60 percent of the population is almost three times that of the bottom 40 percent, and the percentage of individuals with internet access in urban areas is more than twice that of rural areas.44

Despite these disparities, though, digital technologies are providing opportunities for important innovations and increased job opportunities. For instance, Rwanda is using drones for blood deliveries to hospitals and is increasingly reliant on solar power.45 Rwanda is also working to provide 5 million of its youth population with digital training through its Digital Ambassadors Program (DAP).46 In addition, banking through mobile phones has led to an explosion in financial access. Across Africa, there are now more than 100 million people using mobile financial services,47 and African banks now rank second in the world in growth and profitability.48 As the global management consulting firm McKinsey & Company notes, “Africa is the global leader in mobile money,” with an increasingly diversified set of providers and annual growth rates of 30 percent between 2013 and 2016.49

Even with all of these positive developments, the overall volume of U.S. trade with Africa remains relatively low and has been dominated by oil and gas imports from Africa—which have proven to be quite vulnerable to price shocks, particularly after the 2008 global financial crisis.50 However, major U.S. manufacturers such as Boeing see the considerable potential in Africa. Air traffic is expected to increase 6 percent annually to 2034, creating a need for some 1,170 new airplanes, valued at approximately $160 billion.51 Clearly, now is the time for the United States to more effectively engage in trade with Africa given that it hosts some of the world’s fastest growing economies and that more and more of the world’s population will be centered there over time.

Competition on the continent

America’s economic competitors, such as China, Europe, and India, have already been heavily targeting Africa as a market and partner. As the global economy grows ever-more competitive and Africa experiences real growth, the continent cannot solely rely on favorable terms, such as those embodied in AGOA, to drive its economies and is being pushed toward reciprocal trade agreements with more developed nations in Europe and beyond.52

As the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative states:

Even with trading partners on other continents—such as the European Union and China—Africa has been updating and formalizing its relationships. These are generally positive developments. But in some cases they may also pose challenges for U.S. exporters to Africa, who do not have comparable access to African markets and are increasingly finding themselves hemmed out of the African market by their foreign competitors. 53

The United States is frankly already badly behind in Africa. In 2017, the United States accounted for only 6 percent of Africa’s total trade of more than $875 billion.54 This figure was well behind the European Union’s 34 percent share and China’s 19 percent share.55 Interestingly, nearly 60 percent of total U.S. trade with Africa in 2017 occurred with only four nations—South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt, and Algeria—which are some of the continents largest economies.56

Between 2008 and 2017, U.S. exports to Africa declined by 23 percent, whereas China’s grew by 86 percent.57 Over the same period, U.S. imports from Africa declined by 70 percent, largely because of less U.S. reliance on energy imports, compared with a 35 percent increase for China.58

These rather stark figures aside, the United States can enjoy some distinct comparative advantages if it pursues a forward-looking strategy in Africa.

In understanding what makes most sense for U.S. engagement in Africa, it is useful to detail in part how China approaches Africa. While there is certainly a lot of debate about China’s intentions on the continent, China is clearly pursuing a strategy that reflects its own interests in Africa, including in the continent’s vast natural resources and market potential—and African states are responding in kind.

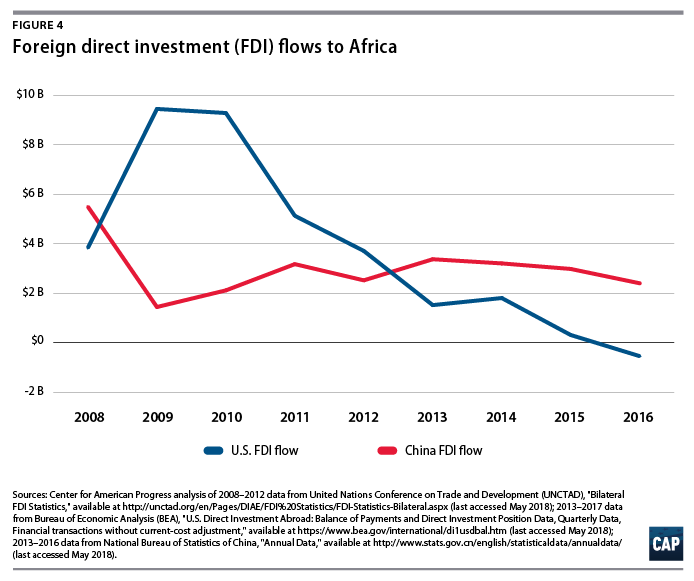

Certainly, Chinese investment on the continent has made an impressive leap forward, growing from $1.4 billion in 2009 to $2.4 billion by 2016.59 Notably, U.S. investment flows over this same time period declined from $9.4 billion to -$5.5 million. Additionally, Chinese aid to the continent has grown, though the Chinese government tends to blur the lines between its foreign aid and other investments and finance.60

As the Brookings Institution notes, China’s approach closely intertwines “foreign aid, direct investment, service contracts, labor cooperation, foreign trade and export.”61 When it comes to Chinese aid to Africa, very little is in the form of grants; instead, most of it in the form of loans that will eventually make their way back to the Chinese treasury. In what has been referred to as the “Angola Model,” China often “provides low-interest loans to nations who rely on commodities, such as oil or mineral resources, as collateral.”62 As a result, recipient nations tend to then suffer from low-credit ratings, making it difficult for them to secure additional funding from the international financial market, which then provides an opening for China to make additional financing “relatively available—with certain conditions.”63 Such conditions might include preferential contracts for Chinese state-owned companies to build infrastructure projects or easier access to a country’s natural resources.

In this regard, China’s approach on the continent rather closely resembles the approach of the U.S. foreign assistance program in the early 1960s, where loans at relatively low interest rates were given to developing countries, often for big infrastructure projects. In exchange, developing countries underwrote these loans with their natural resources, and both parties ensured that a lion’s share of the work on the infrastructure project went to construction and other firms from the lending country.

The United States moved away from such lending practices because it left many developing countries facing a mountain of unserviceable debt.64 But that is only part of the story. One of the other primary reasons that this approach fell out of favor was that it simply was not effective toward the long-term goal of encouraging the political and economic reforms that made development and growth self-sustaining.

The Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies China-Africa Research Initiative estimates that between 2000 and 2015, Chinese financiers provided a total of $94.4 billion in loans to African governments and state-owned enterprises, which have given rise to serious concerns about increased debt levels over the long run.65 Additionally, China’s approach offers vital financial support to any number of governments in Africa, regardless of their track records on human rights, economic reform, or good governance. This is an effective short-term strategy for gaining access to natural resources, but it may also serve to alienate China diplomatically from many Africans over the long term, as they are left to wonder why China was so eager to underwrite governments that repressed them or were openly corrupt.

China has also expanded its engagement on the continent in other areas as well. For instance, China recently announced that it will host the first China-Africa defense and security summit at the end of June.66 China has also increased its role in U.N. peacekeeping missions, contributing more troops than any of the five permanent Security Council members.67 Additionally, China has increasingly targeted African students for scholarships and study abroad opportunities in China. As a result, there has been a surge in the number of African students going to China, growing from 2,000 students in 2003 to nearly 50,000 in 2015, according to Michigan State University.68 China now surpasses the United States and the United Kingdom as a destination for African students studying abroad, however, France still remains the top destination for these students.

U.S. engagement, however, should not be guided solely by fear of a Chinese takeover of Africa. Rather, it should pursue an approach that also incorporates a clear-eyed analysis of the considerable mutual benefits to be gained by both the United States and African countries of genuine partnership in areas such as economic growth, security, the environment, and more. Furthermore, the U.S. approach in Africa must not lose sight of the core imperative to help bolster countries with strong institutions, vibrant trading systems, and respect the will of their own people—that is where the greatest opportunity today lies.

A forward-looking U.S. role

Areas where the United States can most effectively engage with Africa, particularly on the economic front, are best drawn from a sound analysis of the current challenges that continue to put a damper on more rapid growth and trade in Africa and how the United States is positioned to help address them.

Here are some of the key areas that continue to dampen growth and trade on the continent:

- Africa’s markets remain too small and fragmented, too many institutions on the continent are fragile, infrastructure is in need of substantial improvements, and labor productivity in a number of key sectors remains low.69

- There continues to be resistance to free trade in a number of countries such as Nigeria and South Africa where political parties remain eager to maintain control over industrial policy.70 Similarly, a number of countries, such as Ethiopia, have not enjoyed the full benefits of mobile banking or other technological innovations because the state maintains fairly central control over the banking and telecoms industries.

- Africa’s intraregional trade levels are very low with about a third the level of that in Europe or North America, at around 18 percent.71 Much of the heavy lifting to be done here is not through sweeping new trade agreements, but by dealing with the more mundane, daily obstacles to trade across borders on the continent. As The Economist notes:

Research also shows that the largest gains come not from reducing tariffs, but from cutting non-tariff barriers and transport times. That will come as no surprise to drivers in the long lines of lorries queuing at a typical African border post. The World Bank estimates that it takes three-and-a-half weeks for a container of car parts to pass Congolese customs.72

- Many African countries are dependent on commodity prices, which are often prone to rapid rises and falls that create considerable economic shocks in the process. As such, these countries need to pursue a more diversified export strategy.

- Many of even the fastest growing countries in Africa still have large percentages of unbanked populations or percentages of the population that lack internet access, suggesting the potential for even more dynamic growth throughout Africa. Across the continent, roughly 22 percent of individuals use the internet, and roughly 18 percent of households have internet access.73 As noted previously, the proportion of individuals with internet access is not evenly distributed within countries and across different demographic groups, and the distributions also vary between countries. For instance, Morocco (58 percent), the Seychelles (56 percent), and South Africa (54 percent) have the highest percentage of individuals using the internet, as compared with Guinea-Bissau (3.8 percent), Somalia (1.9 percent), and Eritrea (1.2 percent), which have the lowest percentage. For comparison, 98 percent of individuals use the internet in Iceland and 76.18 percent of individuals use the internet in the United States.

- Relatedly, access to electricity across the continent remains the lowest in the world, though there have been notable gains in recent years. Roughly 57 percent of the population in sub-Saharan Africa (around 590 million people) still do not have access to electricity, more than 80 percent of whom live in rural areas.74 However, according to the 2017 World Energy Outlook report, “since 2012, the pace of electrification has nearly tripled relative to the rate between 2000 and 2012,” and for the first time in 2014, “electrification efforts outpaced population growth.”75 Major contributors to these positive developments include Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Sudan, and Tanzania. Additionally, the United States’ Power Africa initiative—which was launched in 2013 and codified into law with the passage of the Electrify Africa Act of 2015 in February 2016—has helped support efforts to increase electricity access. As summarized in their latest report, the initiative has helped provide approximately 53 million people with access to electricity to date.76

What is clear is that the United States should avoid a blanket one-size-fits-all approach to the continent. Many of the steps that will be most influential in driving growth and trade and fostering solid U.S. relations with African states for years to come are very context specific. Everyone will have to see clear economic and political incentives for reform, and there will be a great variety of arrangements that make the most sense.

First and foremost, the United States should be supporting African regional economic integration, by identifying and helping to address the delays at borders caused by bureaucratic red tape, inadequate infrastructure, conflicting or confusing regulations, and lack of uniformity in standards. These steps to increase trade between states in Africa will at the same time pave the way for these countries not only to be more dynamic economically, but it will make it easier for the United States to reach reciprocal trade agreements with them.

The United States should continue and intensify efforts to promote export diversification across Africa, and this is a strategy that the United States has used effectively dating all the way back to Korea and Taiwan in the early 1960s. As the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative observed, “Africa’s economic future depends, in important part, on its ability to add value on the continent to its vast natural resources and agricultural commodities, as well as on its ability to diversify its exports.” Continuing, the office said, doing so “could not only bring more labor intensive links of global supply chains onto the continent and produce more jobs, but it could avoid some of the issues that have made African trade with countries like the United States more difficult.” 77

Given the enormous energy needs in Africa—and the profound impact of energy on almost every facet of development and economic growth—the administration should redouble efforts to make the Power Africa initiative a success. While the administration may have some hostility to the initiative because it began under former President Barack Obama, it has wide bipartisan support, is embraced by the private sector, and is an important complement to any approach to help drive economic growth.

In an effort to provide financing alternatives to China and to become more competitive, Congress and the administration should ensure the swift passage of the Better Utilization of Investment Leading to Development, or BUILD, Act of 2018, which would allow for the creation of a new development finance corporation that can better harness private sector resources for international development.78

Lastly, and this is where the administration would need to shift its approach and rhetoric most dramatically, the United States should renew its commitment to democracy and the rule of law at a time when Africa is demonstrating important, but uneven, progress in that regard. In 2018, there will be elections in at least 24 African countries, and the results of these contests will have an enormous impact on not only these countries but the shape of U.S.-Africa strategic and economic relations for years to come.79

America simply cannot be seen as abandoning its support for democracy and human rights when it has been its clearest and most consistent champion since World War II.

About the authors

John Norris is a senior fellow and the executive director of the Sustainable Security and Peacebuilding Initiative at the Center for American Progress. In 2014, Norris was appointed by then-President Barack Obama to the President’s Global Development Council, a body charged with advising the administration on effective development practices. Norris previously served as the executive director of the Enough Project at American Progress and was the chief of political affairs for the U.N. Mission in Nepal., Norris served as the Washington chief of staff for the International Crisis Group and as the director of communications for U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott. He also worked as a speechwriter and field disaster expert at the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Carolyn Kenney is a senior policy analyst for National Security and International Policy at the Center, working specifically on the Sustainable Security and Peacebuilding Initiative. Prior to joining the Center, Kenney worked with the International Foundation for Electoral Systems, in its Center for Applied Research and Learning. She previously completed internships with the International Crisis Group and Human Rights Watch. Kenney received her master’s degree in international human rights from the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver and her bachelor’s degree in international affairs from the University of Colorado, Boulder.