In September 2017, President Donald Trump put 20,000 teachers at risk of deportation1 when he terminated the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program—the Obama-era initiative that grants temporary protection to unauthorized immigrants who were brought into the United States as children. While thousands of DACA recipients arrive from Asia, Europe, and the Caribbean, the vast majority of recipients come to the United States from Mexico and other Latin American countries.2 In addition to the threat of losing DACA, many Latinx students must also bear the burden of immigration policies that separate parents from their children. Not only is the tenor of the broader immigration debate particularly relevant for Latinx students, but the danger of losing thousands of teachers with protected status compounds an already pressing problem—the shortage of Latinx teachers in our schools, especially in states with large Latinx student bodies.

The benefits of increasing teacher diversity

According to the most recent available data, one-quarter of all students in public elementary and secondary schools identify as Latinx, making them the largest ethnic minority in the nation’s schools.3 In some states, such as California, New Mexico, and Texas, Latinx students make up half or nearly half of the student body.4

While the percentage of Latinx students is high and growing, less than 8 percent of the nation’s teachers identify as such.5 The recent increase in the Latinx population means that the teacher diversity gap—as measured by subtracting the percentage of teachers6 of a certain race or ethnicity from the percentage of students7 of that same race or ethnicity—is largest for Latinx students.

Even though Latinx students face the largest teacher diversity gap of any ethnic group, little data are available on the specific benefits Latinx teachers have on Latinx students. Studies have shown, however, that black students benefit in a number of ways8 from having a black teacher: Their teachers have more positive perceptions of their academic potential and behavior in class; they are held to and meet higher standards of academic achievement; and they are less likely to drop out of school. Evidence also suggests that exposure to diverse teachers can benefit all students—not just students of color—by reducing students’ stereotypes and encouraging cross-cultural social interactions.9 Extrapolating from this research, it is likely that Latinx students—as well as all students—would benefit similarly from Latinx teachers.

Although having a Latinx teacher may benefit Latinx students similarly to how black students benefit from having a black teacher, Latinx students have a unique set of needs. While more than 90 percent of Latinx students were born in the United States, most of them have at least one foreign-born parent.10 First-generation Americans report that they are more likely to face barriers to their academic achievement, such as job and family responsibilities.11 Teachers who have personally experienced these obstacles may be able to provide better support. Latinx students also make up 77 percent12 of the nation’s English language learners (ELLs), and research shows that dual immersion or bilingual programs serve these students best.13 Bilingual Latinx teachers—many of whom were once ELL students themselves—would help to meet the demand for an increasing number of dual-language programs, and would serve as a much-needed resource for Spanish-speaking ELL students.14

Increasing Latinx teacher diversity is also critical for improving the educational outcomes for Latinx students. While Latinx high school and college graduation rates are increasing, Latinx students still fall behind their white and Asian peers in high school graduation rates—by 10 percent and 12 percent, respectively15—and in college completion rates—by 26 percent and 48 percent,16 respectively. In addition, Latinxs are more likely than high school graduates of other ethnicities to attend a two-year rather than four-year college.17 Latinx students who can see that teachers from their communities have graduated high school, attended college, and pursued teaching may be more likely18 to follow in their footsteps than Latinx students who have not had that kind of role model.

Although research demonstrates the benefits of teacher diversity, many Latinx students rarely encounter teachers who share their ethnic background. This issue brief explores the extent of the Latinx teacher diversity gap by state and provides policy recommendations for increasing the number of Latinx teachers.

Examining the Latinx teacher diversity gap

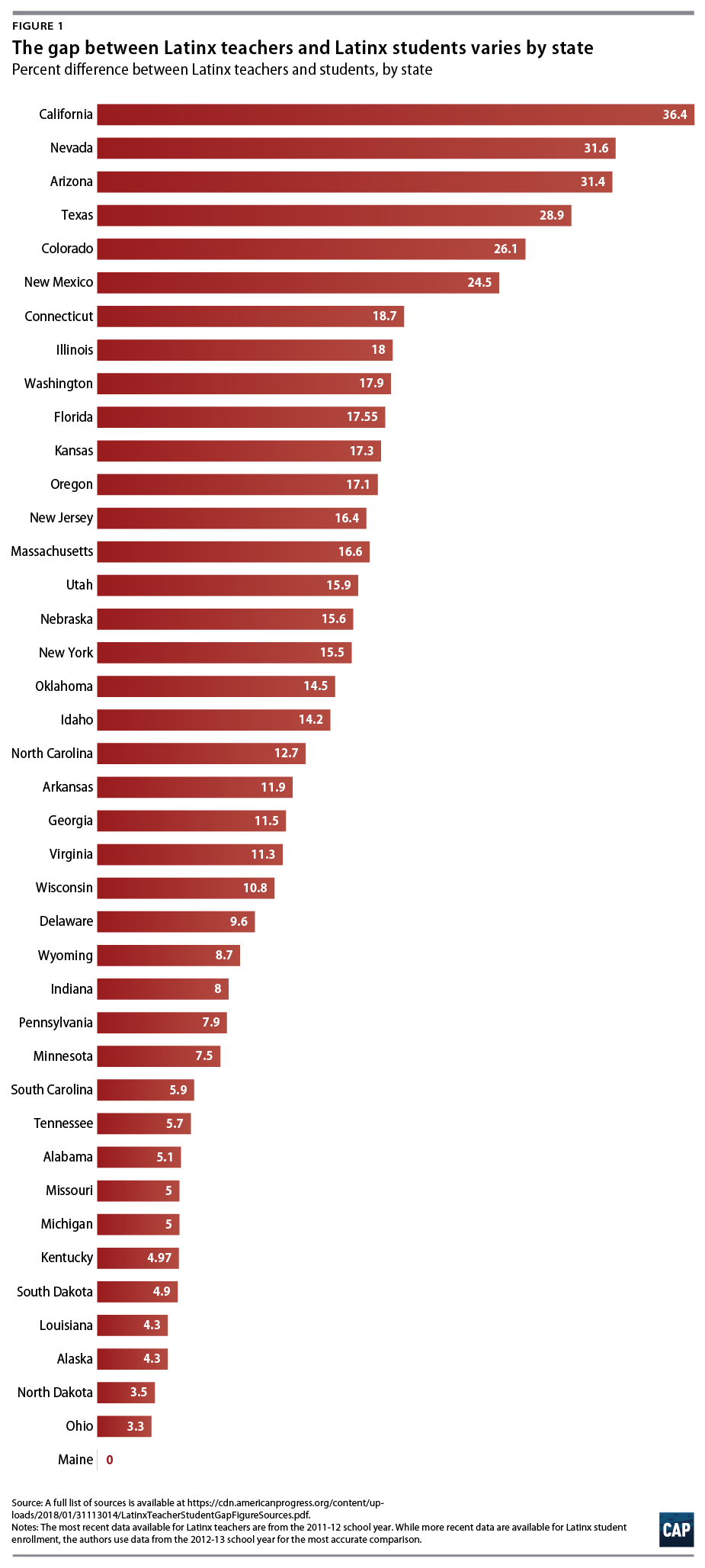

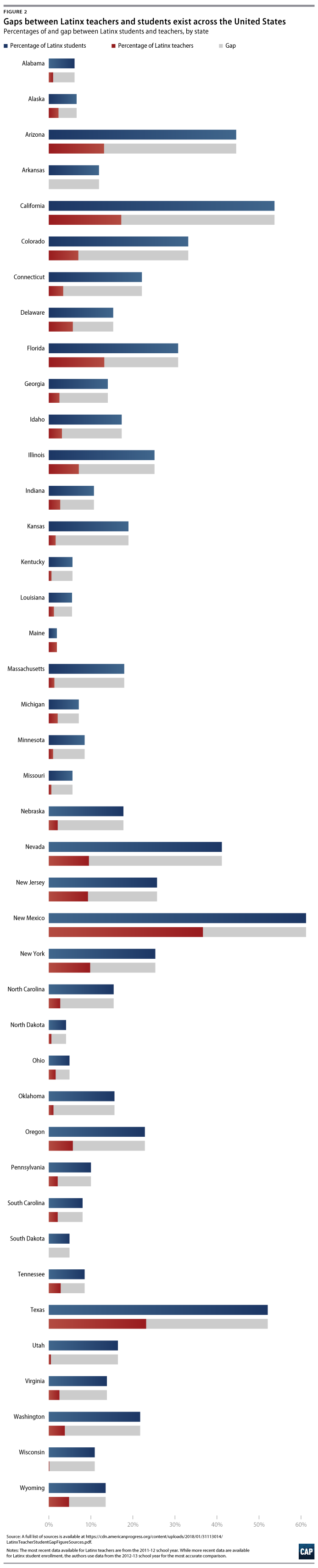

As shown in Figure 1, a Latinx teacher diversity gap exists in 40 of the 41 states with available data. The four states with the largest gaps— California, Nevada, Arizona, and Texas—contain more than half of the country’s Latinx population.19 States with large Latinx teacher-student gaps—between 17 and 37 percent—are also the states with the largest percentage of Latinx students. California, for example, has the largest Latinx teacher-student gap of any state in the country and is also home to the nation’s largest Latinx student population—27 percent of the entire U.S.20 Latinx population, as shown in Figure 2. Teacher diversity is increasingly important in rural areas that have fast-growing Latinx communities, such as North Dakota, Georgia, and Pennsylvania.21 Yet these states have teaching workforces that are only 1 percent, 2.1 percent, and 2.5 percent Latinx, respectively.

Policy recommendations

Pass a clean Dream Act

An estimated 20,000 teachers with DACA protections,22 who are critical to maintaining and encouraging teacher diversity, are currently living under the threat of deportation. Traditional public schools and organizations, such as Teach For America and the Knowledge Is Power Program, employ many DACA recipients who have become an important part of the teacher pipeline in high-need areas—those with a large number of vacant teacher positions or uncertified teachers or those with at least 30 percent of students from low-income households.23 Teach For America, for example, has more than 190 DACA recipients in their teaching corps.24 Although the Trump administration rescinded the executive order, Congress has the opportunity to pass a Dream Act that would provide permanent protections for DACA recipients. Each day Congress fails to pass a Dream Act, however, 122 DACA recipients lose their protections, and this number will only increase after March 5—the artificial deadline set by the Trump administration for Congress to find a solution.25

Increase federal funding to attract more Latinxs to pursue teaching

The low college graduation rate for Latinx students serves as a barrier to increasing the number of Latinx teachers. While Latinx enrollment in public and private colleges reached a record high of 3.6 million26 in 2016, Latinxs are still less likely to graduate from a four-year college than any other racial group.27 According to the most recent available data, in Texas, for example, 34 percent of white students graduated from public universities in four years, while less than 19 percent of Latinx students met the same threshold.28

Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs)—colleges and universities that serve a student body comprised of at least 25 percent Hispanic students29—play an important role in increasing the Latinx college graduation rate and the Latinx teacher workforce. Further investment in HSIs could help to close the Latinx teacher gap, considering that more than half of HSIs are located in the five states with the largest gaps.30 Unfortunately, the current administration proposed a 15 percent cut in funding for both HSIs and historically black colleges and universities—from $577 million in 2017 to $492 million in 2018.31

While maintaining or increasing federal support for HSIs is key to increasing Latinx teacher enrollment in states with large gaps, HSIs educate only 25 percent of Latinx students.32 Federal grants and affordable financial aid are critical for encouraging diversity at all institutions of higher education, considering that the majority of Latinx students who graduate from four-year public colleges do so with debt.33 Yet, the Trump administration’s proposed budget cuts to grant aid and federal loans34 are likely to disproportionately harm Latinx students, who rely on federal financial aid and borrow at higher rates to cover the cost of college.35

Instead, the U.S. Department of Education should increase current funding to elevate Latinx enrollment in colleges and in teaching credential programs. Funding under Title II of the Every Student Succeeds Act provides districts with formula grants in order to support teachers, school leaders, and preparation programs.36 States can reserve up to 5 percent of their funding for the expansion of teacher preparation programs.37 In addition, public universities should leverage existing grant opportunities. The Teacher Quality Partnership Grant Program, in Title II of the Higher Education Act, provides funding to institutions of higher education, high-need local education agencies, and schools for teacher preparation programs.38 California State University, for example, recently received a $8.1 million federal grant to attract more Latinx candidates; to provide students with more opportunities for hands-on training; and to create systems to track student-teacher progress in the classroom.39 The budget should prioritize funding under the Every Student Succeeds Act and the Higher Education Act, instead of cutting programs that attract teachers and improve diversity.

Attract Latinxs to high-quality alternative certifications

States and districts can also fund pathways for alternative certification programs, which help to reduce time and cost barriers for students of color. The National Center for Teacher Residencies, which has 29 programs across the country, provides prospective teachers with classroom experience as they complete their master’s degree.40 Because residents receive a stipend for living expenses and receive a subsidized degree, the program has helped to recruit a group of candidates that has more than double the average number of teachers of color.41 Teach For America, which recruits college graduates to teach for two years while receiving an alternative certification, had a majority-minority teacher cohort in 2015.42 District-level programs, such as the Woodring Highline Future Bilingual Teacher Fellow Program43 in Washington state and the Dual Language Teacher Partnership in Oregon,44 prepare paraprofessionals to earn their teaching certification for bilingual education. While these programs are successfully diversifying the teacher workforce, many of these alternative certification programs have yet to be expanded to states with high demands of Latinx teachers to reduce the Latinx teacher-student gap.

Conclusion

Diversifying the teacher workforce improves student outcomes and supports students of color. Yet, educational achievement barriers—compounded by the Trump administration’s rescinding of DACA and drastic proposed cuts to federal education spending—will continue to keep Latinxs teachers out of the classroom. To close the Latinx teacher-student gap, policymakers need to prioritize access to higher education and high-quality alternative pathways into the teaching profession.

Sarah Shapiro is a research assistant for K-12 Education at the Center for American Progress. Lisette Partelow is the director of K-12 Strategic Initiatives at the Center for American Progress.