North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory (R) signed a bill on August 12, 2013, that created a voter ID requirement, cut early voting, ended same-day voter registration, and eliminated the state’s innovative public financing program for judicial candidates. The public financing program—which gave appellate court candidates several hundred thousand dollars for their campaigns if they qualified by raising a certain number of small donations—was popular with voters, and the vast majority of candidates participated. The program muted the influence of deep-pocketed donors and was in effect for more than a decade, but Gov. McCrory’s budget director targeted it for elimination.

As a result, the recent election was the first in a decade in which North Carolina Supreme Court candidates had to raise large amounts of campaign cash—much of it in large donations from attorneys and corporations with a financial interest in the court’s rulings. The eight general election candidates raised nearly $4 million from private donors. The two 2012 candidates, in contrast, each raised $80,000 in small donations and received nearly $250,000 in public funds for their campaigns.

When independent spending is added, the November 4 high court election saw nearly $3 million in spending, all funded by contributions from attorneys, corporations, and other special interests.

Justice for All NC, a political action committee, or PAC, spent well over $800,000—more than any other organization or candidate. The vast majority of its money came from the Republican State Leadership Committee, or RSLC, a group in Washington, D.C., that helps elect Republican legislators across the United States. One of the biggest donors to the RSLC in North Carolina is Duke Energy, the country’s largest electric utility. The company has given $337,000 to the RSLC since 2006, but its biggest contributions have come in recent years, including $100,000 in the weeks before the November 2012 election. The company recently donated $100,000 to an organization created by the North Carolina Chamber of Commerce that spent hundreds of thousands of dollars in this year’s supreme court race.

Duke Energy’s power plants “produce approximately 49,600 megawatts … to serve approximately 7.2 million customers in the Carolinas, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky and Ohio.” The plants also produced $24 billion in revenue in 2013. The North Carolina-based company wields enormous influence in the state. Gov. McCrory, a Duke Energy executive for 28 years, held on to Duke Energy stock after he took office in 2013, while failing to report the assets as required by law. Facing possible criminal penalties, he filed an amended disclosure. Federal prosecutors are investigating the McCrory administration’s failure to enforce environmental regulations.

The links between Duke Energy and Gov. McCrory’s administration have been scrutinized since February, when a ruptured pipe at one of Duke Energy’s power plants released 39,000 tons of toxic coal ash slurry into the Dan River. The river serves as a source of drinking water for more than 42,000 people in North Carolina and Virginia.

In 2010, the Catawba Riverkeeper Foundation, a group that monitors water quality, found toxins in Mountain Island Lake, a source of drinking water for 800,000 people around Charlotte, North Carolina. Toxins have also been found in groundwater near all 14 of Duke Energy’s coal-fired plants in North Carolina. More research is being done to confirm the source of the contamination. One young resident near Mountain Island Lake, 11-year-old Anna Behnke, reportedly told Duke Energy’s former CEO, “I go to bed every night scared that I could get cancer from that [power] plant.”

Duke Energy has stated that it is “developing a comprehensive long-term ash basin strategy to close basins and safely manage ash. We’re using a fact-based and scientific approach to identify options that protect groundwater and the environment, are good for the communities around our sites and meet regulatory requirements.” The state legislature recently passed a bill to more stringently regulate coal ash ponds, but the Southern Environmental Law Center said the bill does not go far enough. The bill creates a commission to determine how Duke Energy must clean up the coal ash ponds, but Gov. McCrory said he will challenge this provision in court because it overrides his authority to appoint administrative officials.

Some North Carolinians have already taken Duke Energy to court, asking judges to order the company to mitigate the risks to their drinking water. At the same time, Duke Energy has contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars to the biggest spender in the two most recent North Carolina Supreme Court elections. Without public financing for candidates, campaign contributors such as Duke Energy will have more opportunities to try to buy influence in the state courts.

This report examines the success rates of law firms that appeared before the North Carolina Supreme Court from 1998 to 2010 and also made contributions to the justices’ campaigns. The analysis began with a list of attorney donors culled from campaign finance databases. The authors then searched LexisNexis for all cases involving these lawyers or law firms in that election year and the following year. Among the “repeat-player” law firms—those with several cases before the court each year—the firms that gave more campaign cash had higher success rates than those that gave smaller donations. In 1998, the first year of the analysis, law firms donating $400 or more won 53 percent of their cases, compared to 48 percent for firms giving less than $400. The firms that had more than five cases before the court and donated $400 or more won an astonishing 70 percent of their appeals, compared to 33 percent for firms with at least five cases giving less than $400 in donations.

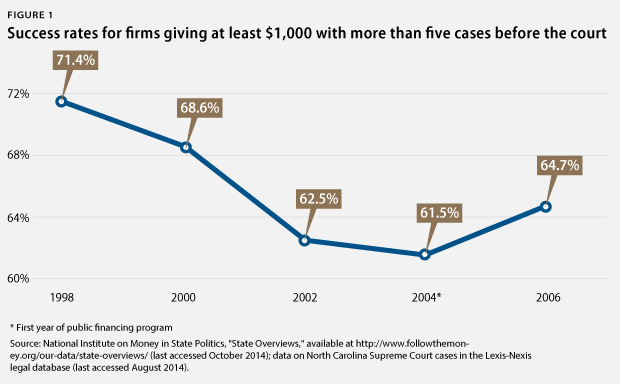

The analysis showed a very high success rate for attorney donors with more than five cases before the bench who gave at least $1,000, but this rate dropped from 71 percent in 1998 to 62 percent in 2004, the first year that the public financing system was in place.

North Carolina citizens must demand that legislators create another public financing system to keep corporations and attorneys from trying to curry favor through judicial campaign cash. Former North Carolina Chief Justice Sarah Parker recently warned, “If people perceive that our courts are for sale, they will lose confidence in the ability of courts to be fair and impartial. … We must have judges committed to the rule of law … without regard to politics, special interests or personal agenda.”

Legislators must restore reforms that ensure judicial legitimacy. Given the U.S. Supreme Court’s approach to campaign finance laws in cases such as Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, North Carolina legislators will have to craft a system that is constitutional and effective in this era of unlimited independent spending. A small-donor matching system could revolutionize judicial elections and mitigate the appearance of bias or impropriety in the courts.

Billy Corriher is the Director of Research for Legal Progress at the Center for American Progress. Sean Wright is a Policy Analyst at Legal Progress.