Introduction and summary

Imagine, later this fall, an alert pops up on your phone: Someone you’ve been in close contact with has tested positive for COVID-19. You voluntarily opted into digital contact tracing weeks ago, once you were satisfied that the program run by your state’s public health authorities respected your privacy and civil rights and wasn’t tracking your location, for a moment like this: You now have a heads-up that you might be infected days before you see any symptoms, if you see them at all. You swipe open to your state’s COVID-19 public health app—it doesn’t work at first, as Face ID no longer recognizes you, or anyone else, wearing a face mask in public—and it guides you through step by step: how to assess your potential symptoms, where to find testing, how to access COVID-19 social and financial support, where to go for help, and whether you need to contact your local public health authority. You call the number provided to book a testing appointment. Reading through the guidance now, you learn that your city wants you to get in touch right away if you’ve been in large groups. You call as directed, and a local public health worker interviews you about your life over the past couple of weeks. Your interviewer thanks you at the end—between increased manual contact tracing and voluntary digital contact tracing, your state has curbed new outbreaks, saved lives, and avoided a return to mass shelter-in-place. Finally, you call your grandmother and postpone your plans together; you’re going to have to self-isolate.

The voluntary digital contact tracing in this scenario, while not a reality today, is one possibility under consideration for future pandemic response programs—but states can only realize this potential by committing to achieving public health goals and safeguarding civil liberties from the start.

In the vacuum of coherent federal leadership, state and local governments are forced to not only meet the immediate needs caused by the coronavirus pandemic but also to prepare for the next phase of public health response.

As outlined in a recent Center for American Progress analysis, ending the coronavirus crisis will require a national stay-at-home policy to break the cycle of community transmission, increased production and distribution of tests and personal protective equipment, protections for the transportation system, improved guidance on face mask use, and rapid contact tracing. This report expands upon our initial recommendations for voluntary digital contact tracing as a key tool to—in coordination with other programs, including mass testing and robust manual contact tracing by public health authorities—end the coronavirus crisis.

Following a discussion of the key challenges ahead, this report provides recommendations and technical guidance to state leaders currently considering digital contact tracing systems as a part of future COVID-19 response programs. These recommendations lay out state strategies for achieving public health objectives and safeguarding civil liberties in the development of digital contact tracing systems. States need not—and should not—develop centralized mass surveillance systems to achieve effective rapid contact tracing. Rather, our recommendations address public health needs while drawing on leading privacy-protective ideas from around the world to recommend a decentralized, data-minimized, and transparent system with appropriate legal, technical, and administrative safeguards. We believe these recommendations represent the easiest and best way for states to develop and release a voluntary digital contact tracing app that will reach the high levels of adoption required for it to work effectively. After all, the best way to make contact tracing effective is for the public to use and trust it—and that will be far more likely if there are real privacy protections in place.

Mobile technology is being used around the world for a number of distinct COVID-19 response purposes—and it has raised a wide range of unanswered questions about both public health effectiveness and its effect on civil liberties and human rights. Such response purposes include:

- Information gathering. Health authorities in Italy have used aggregate mobile location data provided by major cellphone carriers to gauge compliance with lockdown policies.

- Information sharing. Health authorities in South Korea have pushed alerts to residents with COVID-19 updates ranging from reminders about public health guidance to revealing the recently visited locations of newly infected persons.

- Quarantine enforcement. Health authorities in Taiwan have used location-tracking mobile apps to monitor and enforce quarantine.

- Digital contact tracing. Health authorities in Singapore have used digital proximity tracing techniques as a complement to manual contact tracing to identify close contacts of COVID-19-positive residents and quickly isolate them.

- Digital health passports. Discussions have begun around the concept of digital health passports that might serve as individual credentials for proof of immunity in conjunction with future antibody testing. For example, authorities in the U.K. are exploring “immunity passports,” and authorities in China deployed a mobile app health classification system.

The CAP Technology Policy team’s recommendations for state leaders in this analysis are for digital contact tracing as a complementary addition to the increased manual contact tracing recommended by public health experts. Although there are beneficial information-sharing and limited gathering possibilities for a COVID-19 smartphone application, the core challenge addressed in this piece is rapid digital contact tracing and alerting. This analysis does not cover technology applications of any kind for quarantine enforcement or digital health passports, which would require dedicated consideration.

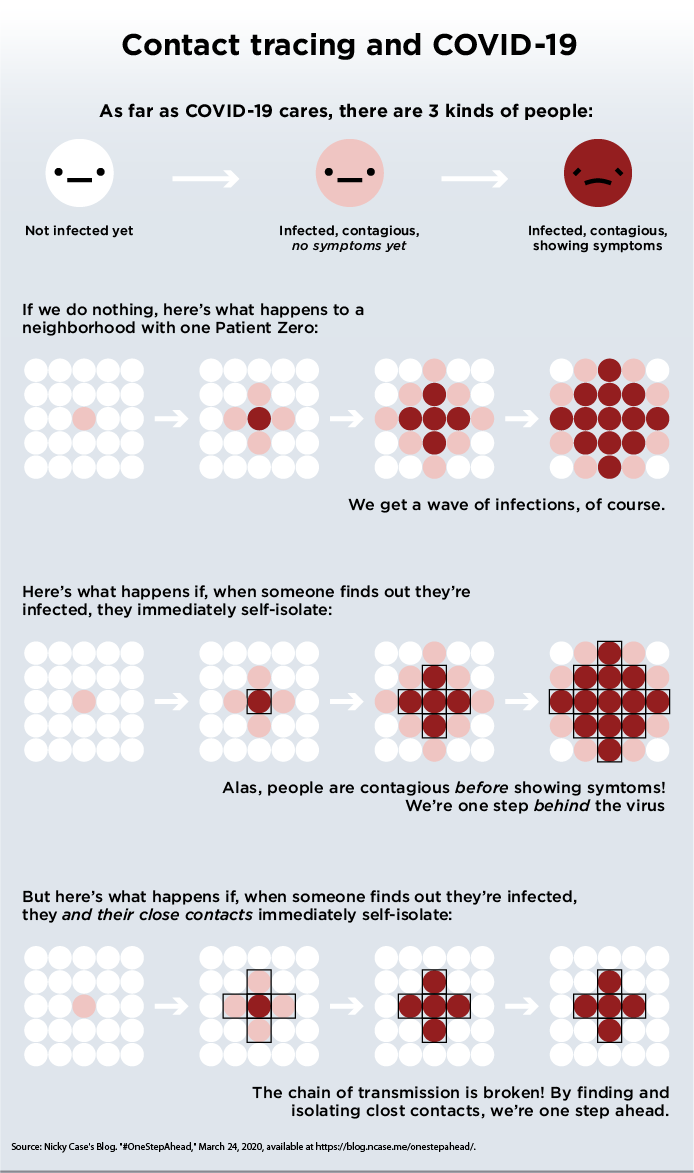

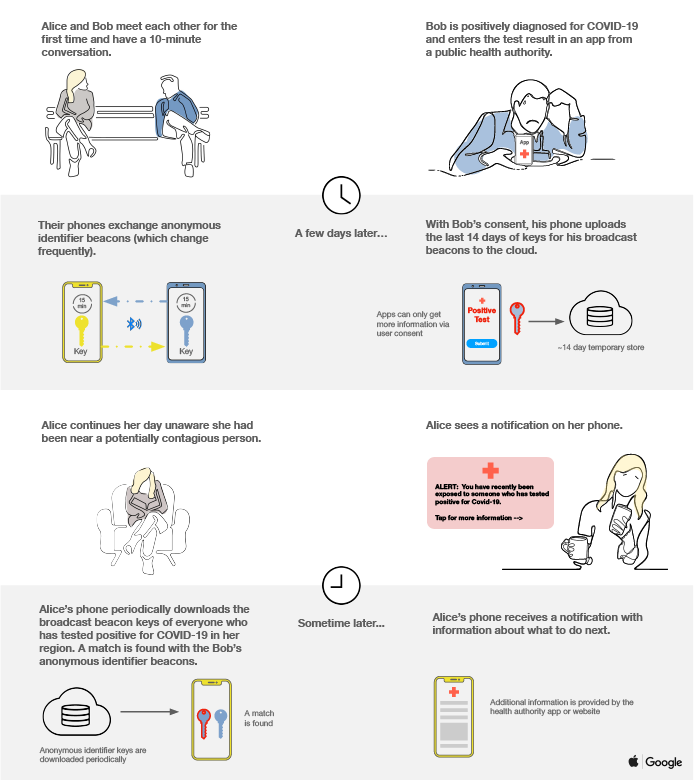

Our previous recommendations for rapid contact tracing utilizing mobile technology stem from the ease of COVID-19’s transmission by presymptomatic or asymptomatic individuals. Up to half of transmissions may occur from asymptomatic or presymptomatic individuals, and models suggest that the longer the delay between symptom onset and isolation, the lesser likelihood there is for contact tracing to control an outbreak. Together, these characteristics suggest that preventing community transmission of COVID-19 through traditional contact tracing alone is difficult. In addition to increased capacity for manual contact tracing programs, technology that enables rapid, distributed digital contact tracing may allow for the breaking or prevention of community transmission, contributing to city and state efforts to reopen parts of their society while preventing new outbreaks. Instantaneous contact alerts will allow potentially exposed individuals to take appropriate action—such as self-isolating, contacting the right public health officials, or seeking testing—while allowing a city or state’s precious public health resources to be focused on confirmed cases. It should be emphasized that rapid digital contact tracing is not a substitute for traditional manual contact tracing practiced by public health departments, which will also require significant investment and enhanced capacity. Rather, digital contact tracing should be considered an additional method through which the general public can participate to assist the efforts to contain the virus. This can in turn help public health authorities focus manual resources on key investigations and better communicate timely information and instructions to residents. Critically, however, the speed of digital contact tracing can significantly aid public health professionals in containing outbreaks.

Traditional contact tracing

Contact tracing is a public health practice used for infectious disease response. State and local public health systems have performed contact tracing for diseases such as tuberculosis and syphilis. Traditionally, public health authorities are informed of a positive test for an infectious disease and are provided with contact information for the person who tested positive. Public health workers perform contact tracing by reaching out to those persons, usually on the phone, asking how they’re doing, and interviewing them to identify persons they have been in close contact with given the particular characteristics of the pathogen. Authorities then notify close contacts and ask them to isolate or seek care appropriately. In this way, contact tracing can reduce the spread of infectious diseases by identifying, informing, and isolating persons who have been potentially infected before they contribute to further spread of the pathogen.

Early efforts from countries first affected by COVID-19 outlined the potential of technology for this purpose—but also the privacy and security drawbacks. South Korea’s efforts to flatten the curve included—in addition to widely available testing, a digitally enabled quarantine enforcement application, and public mapping of cases and supplies—manual government contact tracing aided by mass digital surveillance data of residents’ location, movement, and purchases, as well as digital alerts through the existing mobile telecommunications system rather than an app. At present, privacy-protecting digital contact tracing tools do not exist in the widely available and accessible form that would be required to achieve sufficient adoption among residents, work with existing state-level public health systems, and improve public health outcomes. However, teams of public health professionals and pioneering technologists worldwide have stepped up and developed open source ideas around privacy-sensitive paths forward.

As noted in our initial recommendation to explore rapid digital contact tracing, an ideal system in the United States would be coordinated by a nonprofit entity as opposed to private companies or the federal government. Ideally, such an entity could help states coordinate appropriate civil-liberties-sensitive implementations within each state while also ensuring secure interoperability between state systems to track interstate chains of transmission and address governance and standards issues. We suggested that the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO)—an organization that represents state health officials—might be fit for this purpose. Given its deep expertise and long-standing leadership of the public health community, ASTHO or a similar organization would be ideally situated for this purpose.

Android and iOS interoperability

On April 10, 2020, Apple and Google made a rare joint announcement of a partnership to enable interoperability between Android and iOS devices that would allow public health authorities to build digital contact tracing apps. Initial review of this effort suggests their new program is relatively privacy protective, building on standards advanced by the open source, distributed, encrypted, and privacy-sensitive digital contact tracing efforts occurring worldwide. This announcement answered early technical questions around the general viability of Bluetooth-based contact tracing and removed key restrictions at the mobile operating system (OS) level. Apple and Google’s mobile OS duopoly covers 100 percent of the world’s global smartphone market. Their announcement provides a privacy-protective baseline that state public health authorities can build upon to create successful voluntary contact tracing apps if similar levels of privacy are upheld throughout the design and implementation process.

State coordination on digital contact tracing in the coming months, preferably through an organization such as ASTHO, is made more important by this announcement from Apple and Google. Apple and Google’s effort will create the new de facto international standard for digital contact tracing and will support efforts to enable basic interoperability between apps created by public health authorities in different states or even different countries. This will only accelerate the numerous efforts that are already underway from states, private companies, universities, and independent groups. In practice, this announcement means that Apple and Google’s distributed and privacy-sensitive standard is now the sole viable foundation for a contact tracing app and guarantees a basic level of interoperability with all other apps using the standard. However, it will still require state collaboration in order for separate apps to interoperate to trace interstate chains of transmission. We continue to recommend that states coordinate with one another through an entity such as ASTHO as they consider digital contact tracing systems, which could also provide a coordinated platform for working with Apple and Google both on near-term state server interoperability issues and as the companies move toward contact tracing integrations at the OS level over the coming months.

With this in mind, the following analysis is designed to help state leaders evaluate whether a digital contact tracing system may be an appropriate part of their public health response and, if so, essential strategies for achieving public health objectives and minimizing civil liberties risks.

CAP understands that the potential of digital contact tracing to contribute to the coronavirus response is unproven and that the threat to privacy and civil liberties is very real. Building a technological system to track users—however privacy protective it may be—violates the maxim that the only data that can ever be truly secure are the data not collected. Furthermore, beyond technical and implementation challenges that would be difficult to overcome even in normal times, states must rise to meet the essential challenge of collaborating on regional systems that earn public trust. For digital contact tracing systems to succeed, states must drive high levels of voluntary and opt-in use, which requires the design, build, implementation, and rollout of systems that are worthy of the public’s trust and time. Many state governments will have to overcome government histories of wrongdoing—including government surveillance during the civil rights movement and the criminalization of persons with HIV/AIDS—in order to coordinate between local health authorities, state governments, civil liberties and civil rights advocates, technology companies, the public, and particularly communities that such efforts have harmed in the past. States will also need to coordinate with the other states in their region, as well nationally, to ensure each state’s contact tracing efforts—both digital and manual—work together and achieve secure interoperability and interstate tracing.

However, the coronavirus pandemic poses an extraordinary challenge that requires an extraordinary response. In the absence of viable alternatives, digital contact tracing may offer states a way to prevent new outbreaks of the virus, enable front-line health officials to focus and maximize the use of precious manual contact tracing resources, offer much-needed precision in future public health restrictions, and ultimately enable states to more quickly return to open ways of life. Crucially, Americans will have to trust that the virus can be contained to start even a phased reopening of society and the economy. Recent polling suggests that nearly two-thirds of Americans fear their state government reopening too quickly and that a large majority won’t resume their normal activities right away and instead will “wait and see what happens.” Digital contact tracing can help foster that trust. Voluntary, strongly encouraged, and well-designed digital contact tracing systems could play a key role in allowing the public to take the appropriate measures to prevent another outbreak—alerting residents if they’ve been near someone who tests positive, helping them understand where to get testing, and providing them with needed guidance from public health officials in their area. Apple and Google’s new standards make the pursuit of digital contact tracing smartphone apps a plausible, though still challenging, path forward for states. The voluntary, opt-in, privacy-protecting system described here—deployed by public health authorities and in concert with the broader pandemic response recommendations laid out—could enable states to catch outbreaks earlier, prevent some death and illness caused by the virus, and avoid reentry into the community transmission phase that necessitates broad closures of the economy and society.

To be clear, while we believe these and other benefits will help public health authorities fight the virus, building a privacy-protecting digital contact tracing app that can earn residents’ trust and achieve widespread voluntary adoption is incompatible with building an app that simultaneously provides extensive location history of one’s movements to public health authorities. This means that the digital contact tracing tools created will be primarily focused on distributing contact alerting among residents and pushing important communication and information from public health authorities to residents—but will not result in data dashboards with real-time location tracking and history for public health authorities. Safe versions of such public health information systems can be more easily and safely pursued through separate public health efforts that do not also entail individual-level mass surveillance—such as using aggregated mobility data or health care access. In any case, Apple and Google’s new standards appropriately limit sharing of Bluetooth contact data, and additional state data collection through contact tracing apps will complicate already-difficult trust and usability issues. Put another way, the high levels of privacy and ease of use that will be essential to achieving widespread trust and adoption of an app that must be voluntarily downloaded and authorized cannot simultaneously be achieved with the collection of location, personal, or extraneous surveillance data that might feed public health government databases. We will discuss the appropriate data-minimization strategies in-depth and encourage states to pursue necessary, transparent, privacy-protecting data gathering separate from digital contact tracing efforts.

Overall, our recommendations illustrate numerous areas where achieving both public health and privacy goals is possible in order to contain and address the coronavirus crisis. These aims need not always be held in conflict and indeed can be mutually supporting. Although risks and challenges to contact tracing systems cannot be completely eliminated, both public health goals and civil liberties protections must be pursued to implement safer digital contact tracing systems. Apple and Google’s embrace of a privacy-protective, distributed approach furthers this goal.

The challenge ahead is sobering—no matter what path we pursue. In combination with unprecedented social and economic supports, safe digital contact tracing may have the potential to reduce the ongoing societal damage caused by this pandemic.

Contact tracing and COVID-19

Contact tracing is an important part of the public health response to infectious diseases. Traditional contact tracing occurs manually: State or local public health authorities receive the contact information of persons who have tested positive for an infectious disease, and those people are interviewed by public health officials to identify, contact, and isolate their close and/or casual contacts. By isolating potentially infected close contacts early, contact tracing can contribute to breaking the chain of transmission and slowing disease outbreaks.

In the United States today, public health is primarily a responsibility of tribal authorities or states, which then organize and grant authority to local public health agencies. The organization of the state-locality public health infrastructure varies substantially, but the most common arrangement is a local public health agency serving a single county or city. States have the legal authority to conduct public health investigations and either conduct or grant authority to local agencies to conduct those investigations, which can include contact tracing. Under existing law, public health authorities have access to identifying information of anyone who tests positive for COVID-19 and maintains that information in existing public health databases. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act data use rule has developed around the heterogenous public health system, enabling either state or local public health authorities to access relevant health data and personally identifiable information for infectious disease investigations in certain circumstances.

Contact tracing can be used to prevent disease outbreaks. However, the current state of play limits the possibility for traditional contact tracing as a means to contain the outbreak, as the current focus is on breaking the cycle of community transmission and mitigation. COVID-19 has, throughout most of the United States, already entered a phase of community transmission driven by the lack of available testing and minimal coordination from the federal government. As states and localities look to reopen society, though, it is likely that contact tracing could play a role in helping prevent re-outbreaks before they happen. Following a national stay-at-home period—CAP recommends 45 days starting April 15th, but an end date is subject to clear evidence based conditions being met—the risk remains that there will be resumed infections and a slide backwards into a community transmission period. Contact tracing could play a key role in curbing reemergent outbreaks and avoiding a retreat to shelter-in-place.

Rapid and widespread contact tracing is not immediately useful in the current phase of the crisis but may be especially important in combating a reemergence of COVID-19 and identifying new outbreaks after this initial pandemic crisis passes. Early research suggests that many infected persons are asymptomatic and thus may not take appropriate precautions to prevent spreading the disease to others. Moreover, researchers believe that COVID-19 can have a long incubation period—potentially up to 14 days—during which persons might also not take appropriate precautions. Combined, this means that infected persons may continue interacting with others for weeks before realizing they need to self-isolate, potentially infecting many others. These factors make COVID-19 difficult to stop. Contact tracing—in combination with mass testing, social support systems, appropriately resourced health care systems, and rights-respecting government programs to support self-isolation—could help prevent future re-outbreaks of COVID-19 as societies seek to ease stay-at-home and physical-distancing policies while work continues on developing a vaccine. Such a system could, in the future, enable public health authorities to impose more narrowly tailored shelter-in-place orders than the broad public bans currently in place.

Public health researchers have raised concerns that traditional contact tracing methods alone may be too slow and that faster methods are also needed. One modeling approach suggests that rapid digital contact tracing methods, if able to be widely adopted, have the potential to break the chain of transmission and more effectively prevent future outbreaks. Moreover, the addition of rapid contact tracing alongside manual contact tracing may enable a safer reemergence from lockdown than traditional contact tracing systems alone would allow.

These studies are not without their limitations: Existing COVID-19 contact tracing models are simplifications that include static assumptions about dynamic factors, indicate that success is predicated on high levels of adoption, and call for further research. Moreover, given the immediate crisis, development of such systems would likely need to start before stronger evidence exists that digital contact tracing can be successful. In Singapore, for example, although their digital contact tracing app TraceTogether has been reported on extensively for its potential to help teams of contact tracers work more efficiently, the country recently heightened shelter-in-place recommendations after half of cases could not be successfully traced through their system, potentially due, in part, to limited adoption for such a new app as well as technical usability problems that Apple and Google’s changes address. Deliberation over developing these systems should take into account a lack of evidence thus far, but in the future, deployment of such systems must be contingent on assured efficacy.

Even the best-case digital contact tracing systems, however, are not a catchall solution for stopping transmission. These systems can only stop transmission in coordination with mass, free testing and the social and economic support that would enable infected individuals to self-isolate without putting their livelihoods and their families at risk. Furthermore, contact tracing methods are limited in that they can develop measures to gauge potential person-to-person spread but not transmission through physical contact with surfaces. Finally, systems must overcome a variety of social barriers to achieve the necessary levels of use to be effective—including distrust of surveillance systems and smartphone accessibility concerns, which are discussed later in this analysis.

Fundamental technology questions

While a variety of approaches have been proposed for mobile proximity tracing and public alerting, none has more potential to be effective and privacy-protecting than utilizing Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) for Bluetooth-based contact tracing. Cell tower, Wi-Fi network data, and GPS logs have also been proposed, but they are more difficult to utilize in a privacy-protective way and are not reliably precise enough to gauge whether two users’ devices are within 6 feet of each other—an epidemiologically meaningful distance for virus transmission. BLE is also more energy efficient than GPS, meaning that an app could run in the background all day without quickly draining device battery.

There are numerous projects incorporating BLE for contact tracing, and leading proposals describe a BLE digital contact tracing app that would locally store an anonymous, encrypted, self-deleting record of BLE IDs from devices that a user comes into close contact with for an epidemiologically meaningful period of time. The work of Temporary Contact Number Coalition members, which is both the protocol and the coalition name, and the Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (DP-3T) project, contributed greatly to this accelerated protective development and deserve recognition.

Apple and Google‘s announcement of new Bluetooth-based contact tracing features for the iOS and Android OS incorporates many of the leading locally stored, encrypted, and privacy-centric proposals—very similar to the DP-3T project. The announcement pledged to prioritize user consent, requiring users to opt in in order to participate. The first phase will include new application programming interfaces (APIs) that are accessible only for downloadable apps that are built by verified public health authorities. The two companies also announced future plans to integrate this functionality into the OSs themselves, potentially negating the need to download individual apps. This OS-level integration raises important questions around privacy, civil, and human rights—and does not preclude global public health authorities from building privacy-violating applications on top of their privacy-sensitive standard. The companies have pledged to prioritize privacy, transparency, and consent; Apple, Google, and the public health authorities that build apps based on this platform will need to be carefully held to that commitment. Given the transnational nature of these large technology companies, monitoring their compliance with these promises will need to come from multiple sources, including Congress, federal and state regulators in the United States, other national governments, potential state oversight boards proposed below, as well as traditional civil and human rights groups. Apple and Google also hold the power to prevent governments from building certain kinds of central surveillance apps on their platforms, which raises additional long-term questions outside of this pandemic.

In the new Bluetooth-based contact tracing specification announced by Apple and Google, each user’s device senses the other through BLE and logs the temporary, numerical BLE ID of the other device along with the approximate time the devices were nearby. The BLE ID log is securely stored on each user’s phone for 14 days following their contact. If a user tests positive for COVID-19, they may choose to transfer their list of temporary BLE IDs to a central database run by public health authorities containing the BLE IDs of infected persons. Rather than processing all interactions with infected persons in this central database, BLE IDs of infected persons are pulled by public health apps to each other user’s mobile phone. These apps query the user’s private BLE ID proximity log to see whether any of the infected BLE IDs are a match. The Apple and Google BLE ID log will share whether any of the provided BLE IDs are a match, and then the public health app can notify the user and direct them to take appropriate next steps. Thus, for persons who never test positive for COVID-19, the only data that need leave their phones are a series of temporary Bluetooth IDs, which change regularly as they broadcast to devices around them. In a data-minimized public health app that interacts with the Apple-Google BLE standard, the only data that need be collected and maintained centrally is a database of BLE IDs from self-identified infected persons.

There are open technical questions about Bluetooth-based contact tracing. BLE was not designed for precise distance measurements and indeed varies depending on the environment. While the signal is strongest in close proximity, signal strength can vary widely depending on the type of device and type of environment, making these calculations for viable contact tracing difficult.

With the announcement from Apple and Google on a new Bluetooth-based contact tracing specification, the full hardware and software expertise of Apple and Google can be marshaled to answer these and other technical questions. Their research on topics such as BLE signal strength as a sufficient proxy for distance and any device-to-device signal strength library or references should be made public for reference in addition to being integrated in their APIs and reference documents. Similarly, this announcement answers key questions about viability of Bluetooth-based contact tracing due to limitations of the mobile OS environments. While questions remain around issues for phones that are unable to upgrade their OS—a problem in particular for older Android phones due to OS fragmentation—the clarification that Google will update Google Play services, allowing any device running Android 6.0 or newer, will cover the vast majority of smartphones in the world. Additionally, research from these two companies and the public health authorities who build apps with this new technology on the deployment and adoption percentages required for positive impact should be released publicly to help understand the impact and improve the efficacy of the apps.

The announcement by Apple and Google did not specify if verification of a COVID-19 diagnosis will be required in order to trigger the alert on a Bluetooth-based contact tracing device using their new standard. Press reports have mentioned the possibility of a verification system using QR codes from doctors or laboratories, while others have suggested it may be left to public health agencies that develop companion apps. As with all things that occur online, particular attention will be needed to mitigate potential abuse of false positives by trolls and pranksters.

Apple and Google have created the new international standard for digital contact tracing that, if built correctly, allows for broad interoperability between apps created by public health authorities in different states and even different countries. It provides a necessary privacy-protecting foundation for BLE contact tracing apps but does not prevent against privacy-violating misuse of this data by public health authorities and others. Thus, a truly privacy-protective system will require further safeguards to ensure that public health apps using this standard also use strong privacy-protective design and legally prohibit data misuse.

Challenges for COVID-19 digital contact tracing in the United States

In addition to these broad limitations, there are also a number of specific challenges that U.S. states and localities must overcome if they determine that rapid digital contact tracing is an essential part of their COVID-19 public health system recovery response.

First, unlike other nations that have pursued robust digital contact tracing programs, the United States is characterized by the decentralization of health care, public health, and health insurance systems, as well as limitations around the accessibility and availability of health insurance. Coupled with the lack of available tests, there exist numerous challenges for individuals seeking testing and treatment for COVID-19. For those who do get tested, there is a patchwork of public and private, local and national, professional, and Food and Drug Administration-yet unapproved at-home testing mechanisms. State and local leaders may face challenges in routing all positive test results to public health authorities as testing options continue to proliferate, which would hamper contact tracing effectiveness. States must thus invest in enhancements for systems that securely hand off diagnostic information about confirmed cases to public health authorities. If sufficient testing and diagnostic infrastructure cannot be developed, states will need to explore approaches to reviewing and verifying self-reported suspected cases of COVID-19. In the existing public health system, public health authorities already have systems in place to receive the personal contact information of persons who have tested positive with infectious diseases. Any contact tracing program that enables a new self-reporting mechanism will need to be carefully designed to limit the potential chaos that could be caused by misreporting or false reporting of positive cases. Any barriers to residents procuring COVID-19 tests—financial, logistical, or otherwise—and any barriers to state or local public health authorities receiving complete reports of positive results must be resolved for contact tracing to work.

Second, early studies suggest that digital contact tracing programs would need widespread adoption to stop the spread of COVID-19. New estimates suggest that in a range of scenarios, for a city of 1 million people, approximately 60 percent of the population or 80 percent of smartphone users would need to participate. It should be repeated that a digital contact tracing app will only be successful if other conditions to end the coronavirus crisis are also achieved—particularly the widespread availability of testing—in order to provide confidence and trust in this new public health system. As discussed below, states must overcome numerous social and logistical challenges to achieving sufficient adoption through voluntary downloads and opt-in participation.

Third, states must recognize that public fear of government and corporate mass surveillance is justified. Both malicious and well-intended government actors carried away by the fears of the moment have used crisis moments to extend and entrench control of the general public and, specifically, religious persons, people of color, LGBTQ people, the disability community, and others. The history of government surveillance in the United States during the civil rights movement to address the crisis of demands for equality looms large in this moment. Calls from numerous global civil and human rights groups highlight the inherent civil liberties risks in mass, digital public health surveillance programs. Unfortunately, their fears are already being realized in the coronavirus programs that authoritarian regimes are pursuing. In addition to commitments to transparency and oversight, there are technical strategies to minimize risk to civil liberties, avoid mass surveillance, and prove to media, watchdogs, and the general public that state systems are safe and privacy-protecting. Several of these strategies are discussed in the recommendation section below. The privacy-protective specifications released by Apple and Google make this easier to initially achieve, though that spirit must also be legally and technically adhered to by the applications that state public health authorities put forth.

Fourth, state governments building apps to combat this virus will face technical, procurement, and operational challenges. The recent announcements from Apple and Google will make this task easier and—while they have set forth a useful standard—state-level servers, maintenance infrastructure, coordination bodies, and governance programs will also be required. This would be a difficult undertaking even in the best of times, with sufficient development time and plentiful resources. The pandemic does not make it easier. We continue to recommend that states build nationally interoperable systems and coordinate governance issues, potentially through, as mentioned earlier, a national public health focused nonprofit organization such as ASTHO.

Given the limited time and resources, public health risks, and civil liberties risks, initial investment and effort are essential now. However, continued investment in digital contact tracing systems should be contingent upon efficacy—something that must be monitored as the world moves forward with digital contact tracing.

Digital contact tracing recommendations for state leaders

In coordination with mass testing, manual contact tracing, significant investments in public health and health care infrastructure, and sufficient social and financial support for all Americans, voluntary and privacy-protected digital contact tracing may play a role in helping state authorities prevent new outbreaks and more safely reopen society.

Although there are numerous obstacles to safe and successful deployment of digital contact tracing systems for COVID-19, taking a privacy-by-design approach—in which privacy is prioritized at every stage in the design and development lifecycle—can, in many cases, make for more efficient and secure systems. Building distributed, data-minimized systems can be good for security, public welfare, and public health. Recent announcements from Apple and Google make it easier, though still challenging, to create a safe digital contact tracing application. The recommendations below seek to highlight approaches that meet the need for rapid contact tracing while taking into consideration the important technical, implementation, and civil liberties challenges ahead. Ideally, states will take these recommendations into account in coordination with ASTHO and state partners to collaborate on a shared state-level digital contact tracing roadmap together with Apple and Google.

1. Embrace distributed technology by default

To achieve effective, rapid contact tracing without building a mass surveillance system, states must choose technical decentralization through data localization—the process of retaining data and processing locally on users’ devices rather than centrally. Piping the contacts of every person in your state into one database is unnerving, unnecessary, difficult to secure, risks intrusion from law enforcement, and would invite almost certain legal challenges. Rather, best practice is to build tools that enable distributed, secure, local contact tracing systems. The recent announcement from Apple and Google aims to support a primarily distributed approach. Given that, between them, Apple and Google operate on nearly 100 percent of the mobile smartphones, this announcement has created the new de facto international standard for digital contact tracing and may allow for basic interoperability between apps created by different public health authorities. This approach does not eliminate risk of identification and does not prevent public health authorities from collecting additional personal data and combining it with BLE data to determine location or social network. These issues will require further privacy scrutiny but are an improvement on proximity logging using cellphone numbers, location, or other personal details. Decentralized, encrypted approaches are a great foundational strategy for safeguarding civil liberties while building urgently needed systems.

2. Voluntary systems are more ethical, useful, and likely to be downloaded

With digital proximity tracing systems, the most important system requirement is trust. Building and operating a trustworthy system is essential to encouraging use, driving sufficient adoption, and achieving public health aims. Apple and Google’s recent announcement means that voluntary opt-in systems are essentially the only realistic option for Bluetooth-based mobile phone contact tracing. States are unlikely to be able to compel mandatory app download or participation in contact tracing programs and rather must earn trust around this system through good governance, transparency, strong privacy protection, and putting maximum control in residents’ hands through voluntary use and opt-in participation. By doing so, they will enlist users’ sense of civic duty and public good while creating space for users with differing privacy needs to utilize the app.

Achieving sufficient voluntary adoption is not a trivial challenge, but states can meet it by recognizing the existing needs of residents and providing a range of usable, privacy-safe features that are attractive to users and to state health officials. While Bluetooth proximity logging would be a core feature to which users would need to opt in, states may have additional use cases where getting input from or providing information to users through additional opt-in features would help public health response. A number of voluntary and privacy-protecting features might be useful for different public health systems—for example, soliciting input on what residents need, initiating Q&A features that help residents cope, updating residents on the latest state guidance, providing self-diagnosis quizzes based on the latest research, and providing residents with nearby test sites or clinics to help them get care. In particular, public health officials have expressed desire to narrowcast public alerts to the phones of people in certain areas, which might be accomplished in a privacy-preserving way by sending alerts to all apps but letting the apps locally determine, with a user’s prior permission, whether they are in the relevant area for the alert. Whereas users may reject mandatory participation in these or related state digital efforts as invasive and worrisome, voluntary participation is the best way to earn residents’ trust while strongly encouraging adoption by providing useful features and appealing to a desire to help the public good. Given the strong interest in citizens to combat the coronavirus crisis, we believe it is achievable to reach sufficient adoption—estimated at 60 percent of the population in some scenarios—of a digital contact tracing app if it is built the right way. There are opportunities early in the deployment to build trust through examples of a few successful initial alerts that can grow word-of-mouth recommendations that will grow adoption.

3. Minimize data for secure and trustworthy systems

Building a system that minimizes data collection is not only a good way to protect civil liberties, but it’s also a practical approach to building during a crisis. With investment in initial design of a secure, data-minimizing system, states can build lean systems with fewer short- and long-term security risks and improved usability. Although it’s tempting to collect “just-in-case” data that public health officials may or may not need, these data can be difficult to secure, easy to exploit, and waste precious development time. Moreover, increased data collection will mean decreased trust from users—without which the system cannot succeed. Together, voluntary use, opt-in data collection, and data minimization provide a strong foundation for a system worthy of residents’ trust.

Data minimization is not only a best-practice data protection and privacy strategy; it’s also a practical and agile approach that suits the time and resource constraints of the moment. Once the minimal amount of data is collected, it should be, as noted, stored locally where possible, hosted in the United States in the case of infected persons’ proximity logs, legally restricted in use and sharing, and stored with best-in-class security in each instance. Along with cryptography and cybersecurity, privacy by design is a well-established field of practice, and states will find ample resources in each for making good design choices at the outset to enable lawful, well-defined, secure systems moving forward.

Furthermore, data should be temporally minimized. States must commit to building a system for specific, temporary use in the immediate crisis. From the outset, states should direct technical teams to build in rolling data expiration for both mobile phones and state data trusts of anonymous proximity logs of infected persons. There is no epidemiological reason to retain data beyond a limited, epidemiologically determined time period. While the lessons from deploying contact tracing systems must be carried forward, the temporary system developed for COVID-19 should only be used for COVID-19. Residents should not be expected to participate in this program in perpetuity, and thus automatic expiration of data, systems, and processes should be incorporated from the outset.

For COVID-19 tracking, an important part of thinking through data minimization is recognizing the distinct data requirements for user groups. For example, an effective contact tracing system could enable anonymous proximity sharing from COVID-19-positive users but wouldn’t need to share proximity data from healthy users. Moreover, existing public health systems already have names and contact information of COVID-19-positive people to enable traditional contact tracing. A new digital complement thus need not collect this same information from healthy users or infected users. Similarly, digital contact tracing in apps for use by the general public can be accomplished through Bluetooth signals alone and does not require additional collection of GPS location data or nearby Wi-Fi networks. GPS data and Wi-Fi network data should thus not be collected as a part of proximity logging from a data-minimization standpoint, which adds to a long list of reasons not to collect these data from security, usability, civil liberties, battery life, and accuracy points of view.

4. Build trust by limiting scope creep

Avoiding legal and technical scope creep from day one is good for technical development, good for civil liberties, and ultimately, good for building sufficient trust with residents to make widespread adoption possible.

In parallel with achieving data and purpose limitation through data-minimized design, an accompanying legal framework should put appropriate safeguards on the use and purpose of any digital contact tracing system. State legal teams should develop binding guidelines that use the force of law to limit the purpose and use of the system explicitly for public health purposes. Policymakers should prohibit commercial parties from recording contact tracing beacons emitted by the system and from using the system’s information for any commercial purpose except public health functions specifically authorized by health officials. Furthermore, law enforcement and any other federal or state agencies—including the National Vetting Center, the U.S. Department of Defense’s Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency, and local Joint Terrorism Task Forces—must be explicitly prohibited from gaining access to any part of this system for any reason. Policymakers must establish at the outset that this system must never be used for any purposes other than epidemiological contact tracing for the current COVID-19 crisis. Within that, if existing public health authorities as they currently exist need to be modified, any changes should legally sunset at the conclusion of the COVID-19 crisis.

Using legal safeguards and well-established best practices around data security, data protection, and data minimization, states can be strategic about using their limited time and resources to build systems that simultaneously meet public health needs and essential civil liberties protections. Without public trust, digital proximity systems will fail and be unable to reduce future COVID-19 outbreaks and infections.

5. Lead and partner with transparency

Committing to transparency from the start can support quality development and productive collaboration while safeguarding civil liberties. States and localities should plan for transparency on technical and administrative levels.

In terms of technical transparency, successful efforts will both use open-source repositories and make the code for their own contact tracing system open, along with technical descriptions justifying privacy claims made about the system. Open-sourcing technical systems is a well-established practice in technical communities—including civic tech, gov tech, and digital service delivery—and will make for better systems. In a time of limited capacity, open-source processes are a great way to invite local and global experts to help overcome barriers and minimize duplicative work. To this end, and to contribute to collective progress on these systems, it is critical that states follow the guidelines outlined in 18F’s state software budgeting handbook and ensure that any contracts for this work reflect those principles but with an emphasis on being released to the public domain or under an open-source license. Key guidelines such as requiring the software source code be written and maintained in public on a social-coding platform (e.g., GitHub or GitLab) from day one and that the software be explicitly dedicated to the public domain or published under an open-source license are essential. This is the single best way to prove that a technical system does exactly what it says it does, enabling techies, civil liberties advocates, and media to communicate to the public that they should indeed trust and participate in the contact tracing program. It will also allow other states or localities to reuse any development work for their own efforts to further the cause of defeating the virus.

In terms of administrative transparency, being clear about the legal framework and authority in which the system is implemented will be an essential component in guarding civil liberties and building public trust. States will also build essential trust by clearly defining and explaining system operation and the authority that makes it work. Regular, straightforward reporting on adoption and success will familiarize media and the public with the system and build trust over time.

Given the urgency, it’s also essential that any partners—technical or administrative—are values-aligned. A group of states, localities, companies, universities, independent efforts, and volunteer coalitions are racing toward potential digital contact tracing solutions, and it’s likely that the coming changes from Apple and Google will better enable states to collaborate with these projects. Leaders may be able to save time and move more quickly toward interoperability by collaborating with existing efforts but will need to take caution in assessing potential partnerships. Any partnership that does not clearly reject data sale, data sharing with anyone but state and local public health entities, and data use for any purpose other than state and local public health use should be rejected. Any vendor who attempts to sell their solution but requires proprietary data formats, nondisclosures requirements, or refusal to open-source technology is not one that is placing the priority of saving lives at the forefront. Any effort that pays lip service to privacy but does not build in strong privacy and data protection by design should be rejected. Throughout, states, localities, or nonprofit intermediaries should be in control of data storage and processing. Any and all partnerships should be clearly disclosed and defined.

6. Design with public health workers and residents to provide clear benefits for both

Successful civic and technical systems are those designed in close coordination with, or led by, the people who will use and be affected by those systems. In this case, that includes public health workers and state or local residents. To succeed, a digital contact tracing system will need to be designed with and provide benefits to both user groups. This might include learning from and understanding existing barriers to COVID-19 contact tracing from public health workers and having a clear understanding of how information flows in the manual contact tracing process. Given the current strain on existing front-line workers, policymakers and the team designing any digital contact tracing app should consider also utilizing recently retired and former public health workers to provide some of this needed input and guidance.

For users, this means designing an app that successfully communicates and provides them with unique value during this crisis. At a minimum, this includes keeping themselves and their loved ones safe by learning if they’ve been in close contact with infected persons, contributing to the public health of the community, and aiding public authorities and their communities in preventing outbreaks, saving lives, and potentially avoiding a return to widespread shelter-in-place.

This will require upfront investment in understanding residents’ needs and fears around COVID-19 and especially the feelings of residents with varying accessibility needs, technical abilities, language skills, wireless connections, and privacy concerns. In addition to appealing to residents to support collective response, system design should think realistically about the existing needs of residents around COVID-19 and ways to meet those needs in a data-minimized way. Through this process, states may discover additional benefits that they can provide to users in a privacy-protecting way that further adds value and drives needed adoption. State public health authorities will also need this process to carefully design and communicate systems that can encourage appropriate testing, support residents in seeking care, and support residents in safely self-isolating. To be clear, the barriers here are not only technical: Because of the financial and other strains that self-quarantine may impose on someone exposed or confirmed infected, states should explore designating funds that could be used to provide financial or other supports to patients, as needed, to ease strains associated with compliance with self-isolation. Federal funds should be allocated to assist the states with these efforts.

States need not build these processes from scratch: There is a wealth of civic design expertise that will help states build these systems in a safe, effective way from the start. Investment in designing with public health workers and residents will ultimately save development time and result in a more effective system. By investing in good, inclusive design at the start, states can lower risk of failure, which may further damage residents’ trust and hamper future efforts.

7. States should appoint an independent privacy and civil rights advisory board

Trust is not assumed but earned, particularly as leaders need residents of their state or city to download an app and give it access to personal mobile phone capabilities. One way to foster trust in a system is to proactively identify this trust issue; as such, states or governors should appoint a board to help guide and oversee this initiative. This board should include elected officials, public health officials, technical and legal experts, and key communities and stakeholders as full members of the board. These stakeholders should include representatives from communities that are already over-surveilled, including people of color; communities that are particularly affected by the biases of the existing health care system; communities that are being left out in other aspects of the COVID-19 response, including the disability community; communities that are being targeted because of the federal government’s racism around COVID-19, including the Asian American and Pacific Islander community; communities with preexisting or chronic health conditions; and communities that face additional danger due to existing COVID-19 response policies, including survivors of domestic violence and front-line workers providing essential services. The board should be empowered to hold public hearings, compel the production of documents and testimony from witnesses, and be able to issue public comments and reports. Any additional data collection or data transmission functionalities should have to be approved by the board.

8. Governors must be at the helm

It is far too easy for technical projects of this scope to get lost in a bureaucracy at the best of times and even easier to imagine in this crisis. If a state decides to move forward with a technological solution to contact tracing, the team will require both an experienced technical lead and an experienced bureaucracy hacker. Drawing on the experience of the U.S. Digital Service teams at the federal level and state Digital Services teams, this project must report directly to the governor or within one reporting line to the governor—such as a lieutenant governor, chief of staff, or deputy chief of staff. It must have regular visibility, protection from other interests, and the ability to coordinate input from a bureaucracy without being overwhelmed by it. It will require dedicated technical, procurement and contracting, and legal resources. States that do not have existing Digital Services should consider reaching out to leaders experienced in navigating complicated technical developments in government such as the U.S. Digital Response, a volunteer-run, nonpartisan effort to provide free assistance on technology issues to government during COVID-19 crisis. This is not a project that can be solely outsourced to a vendor; due to the political and operational sensitivity, it will need to be carefully guided and protected.

9. Pursue regional collaboration and national standards

Without interstate interoperability, digital contact tracing systems will be severely limited in their ability to track chains of infection across state lines. As previously recommended, state systems could be nationally coordinated by a nonprofit entity—for example, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO)—to ensure that they can easily collaborate, learn from one another, and set data standards to allow states to securely share anonymous proximity data for persons travelling across state lines. Moreover, such an entity could play a role in facilitating the development of complementary governance strategies to anticipate and manage the future technical, security, and privacy issues that are likely to emerge. A trusted, transparent, and technically sophisticated body could be a key asset in helping states effectively respond to these issues while maintaining public trust.

Whether for timing, public health authority, or implementation reasons, states may be independently pursuing their own systems. CAP’s recommendation remains that states should collaborate with ASTHO on these systems and at a minimum coordinate by region: Public health authorities must have the ability to track chains of transmission interstate for state-led solutions to succeed. This is true everywhere, and it is only made more important for states with overlapping metro areas (e.g., the New York metro area or the Kansas City metro area). Early-stage technical and design decisions made in coordination with neighboring states can save time and headache down the road, increase the likelihood of secure interoperability, and potentially achieve improved public health outcomes. With Apple and Google’s announcement, working toward this will be easier because of emerging standards, but ASTHO could provide a much-needed forum for effective coordination between states, Apple, Google, and other supporting entities particularly as they move toward integration at the OS level.

Working with ASTHO or in discussions between regions, states should also consider entering into a development consortium that could develop a single white-label app and infrastructure, which could be distributed with different branding and back-end infrastructure in each state or region. In other words, a desire to label something clearly as the product of one’s own state or region and to store associated data does not force states to develop their own systems, and indeed regional and national collaboration will only support states’ efforts to build a safe, effective system for residents.

Conclusion

We are in the midst of a period that will reshape and reorder vast swathes of American society. Following the immediate and essential needs CAP outlined in its recommendations for mitigating this crisis and reopening the economy—including mass testing, increased traditional contact tracing, sufficient PPE and expanded health care capacity, a national stay-at-home order, and sufficient social and financial support for all Americans—privacy-protecting, voluntary, and distributed digital contact tracing may be able to play a key role in our ability to reopen our society and economy.

Digital contact tracing apps may allow all of us to better fight this virus and return to more open ways of life. A voluntary digital contact tracing app with opt-in participation—well-designed in coordination with both state public health authorities and residents, privacy-protecting, and highly incentivized—could play a key role in enabling states to prioritize resources and provide information while allowing the public to take the appropriate measures to prevent another outbreak.

In this pandemic, there are no silver app solutions. No new app will end this crisis tomorrow—and indeed, it is not without the potential to make it worse. In reviewing the options, we come to the recommendation of distributed digital contact tracing reluctantly and only in the context of exploring the range of other recommendations. However, we find hope in the idea that new approaches make it possible to build this in a maximally privacy-protective way.

We need a humble, clear-eyed, and critical approach to the broader picture and the multifaceted challenge ahead to contain the coronavirus. In particular, all stakeholders must be at the table and key safeguards need to be in place to ensure that any technology used by public health systems works to help defeat COVID-19 without bringing worse long-term outcomes for the public and already marginalized communities. It will be difficult, but everything about the coronavirus crisis is difficult—and it is a challenge that we can weather with proper leadership, clear guiding principles for the privacy of the public and needs of public safety, and an all-hands-on-deck approach.

Erin Simpson is the associate director of Technology Policy at the Center for American Progress. Adam Conner is the vice president for Technology Policy at the Center.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the following persons for their contributions to this piece and the discussions to develop it: Ed Felten, Lauren Smith, Harper Reed, Frank Long, Andrew Trask, and Emma Blumke of OpenMined; the U.S. Digital Response team; and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials.

The authors would like also like to acknowledge and thank the following Center for American Progress colleagues for their contributions to this piece: Neera Tanden, president and CEO; Mara Rudman, executive vice president of policy; Ben Olinsky, senior vice president of policy and strategy; Topher Spiro, vice president for Health Policy and senior fellow for Economic Policy; Danyelle Solomon, vice president for Race and Ethnicity Policy; Rebecca Cokley, director of the Disability Justice Initiative; Maura Calsyn, managing director of Health Policy; Jocelyn Frye, senior fellow for the Women’s Initiative; Jeremy Venook, research analyst; and Nicole Rapfogel, research assistant for Health Policy.

To find the latest CAP resources on the coronavirus, visit our coronavirus resource page.