Conservative governors and legislators across America are angry at the third branch of government. Some of these lawmakers are pushing legislation that could throw judges off the bench, while others are pushing to limit judicial authority. In one state, a governor unilaterally removed a justice of the state supreme court. Another Republican governor has publicly vowed to defy a ruling in a pending case if he does not like the outcome. Many of these proposals violate the separation of powers principles in their respective state constitutions. But some of these politicians want to amend their state constitutions to give the executive and legislative branches exclusive control over judicial appointments.

This conservative backlash is a response to court rulings that require the legislatures to spend more money on education or to distribute those funds more equally. These proposals send a message—a warning to judges that legislators have the means to punish courts that rule against the state.

These threats to judicial independence emerged in Kansas, for example, just before the state supreme court ruled in favor of poor school districts seeking to restore hundreds of millions of dollars in funding that legislators had recently eliminated. On March 7, 2014, the court ruled the education-funding system unconstitutional and gave the legislature until July to fix the deficiencies.

Republicans had warned the justices not to order a specific increase in funding. Gov. Sam Brownback (R) and Senate President Susan Wagle (R) recently said that such a ruling “could push lawmakers toward trying a constitutional amendment to change the way justices are selected,” according to The Wichita Eagle. These politicians brazenly issued explicit threats to the independence of the Kansas Supreme Court.

This backlash comes as more courts are taking a stand to enforce constitutional provisions requiring states to provide an adequate education for all students, not just those in districts with more valuable property and more property tax revenue. The increasing focus on measurable results—in the form of student testing—in education has changed the nature of the judiciary’s role in education funding. “The states have promulgated content standards, assessment systems—they’ve promulgated lots of accountability,” said David Sciarra of the Education Law Center. “But what the states haven’t done is determine the cost of delivering standards-based education to all kids.” With measurable goals and testing data, courts can more easily determine whether a school system is achieving its goal of educating students. William Koski of the Youth and Education Law Project said the courts “are playing a proper role in not establishing what kids should know and be able to do, but holding the legislature accountable to what it says kids should do.”

These cases often stem from litigation that began decades ago. In some states the respective high courts had recently deemed the education-funding systems constitutional. But when the 2007–2009 recession led to falling tax revenues, many legislators responded by cutting money for education. These cuts led the New Jersey and Kansas high courts to restore judicial oversight of school financing.

These state supreme courts are the only institutions standing in the way of conservative legislators’ austerity agenda for education. But if these legislators get their way, state supreme courts will not serve this role. Education would be left to the whims of legislators who might not care about students in districts with fewer resources. If advocates for better education want courts to order legislators to fix broken schools, they must act to protect judicial independence and ensure that courts can enforce constitutional mandates without fear of retaliation.

These lawsuits to enforce constitutional education mandates have helped to equalize the funding for schools with students who are often from groups that historically faced discrimination in education. For example, a group of Alaskan school districts and students sued the state in 2004, alleging that the legislature had failed to satisfy its constitutional obligation to provide an adequate education. The plaintiffs were rural districts, most of whose students were Native Alaskan. The plaintiffs emphasized the achievement gaps that suggested Native Alaskan students and poorer children were not meeting the state’s educational goals. In the 2004-05 school year, only 43 percent of Native Alaskan 10th graders were proficient in reading, compared to 82 percent of white students. Given the importance of early childhood education to future success, an unfair educational system is a barrier to social mobility.

While the state of Alaska had formally abolished its separate school system for Native Alaskan students, the achievement gap suggested that not much had changed. One of the plaintiff districts, Bering Strait School District, had a student body composed entirely of Native Alaskan children, 80 percent of whom were “limited English proficient.” Fewer than half of the district’s students were proficient in language arts, and only 37 percent were proficient in math. One superintendent told the court, “It would take about 69 years … for all children in the district to be proficient at its current rate of improvement.” The plaintiffs warned that “even if districts are able to maintain the current rate of improvement, generations of children will be lost.”

Although the trial court conceded that more funding alone was not the solution, it concluded that “the State has failed to take meaningful action to maximize the likelihood that children at these troubled schools are accorded an adequate opportunity to acquire proficiency … when a school has demonstrated an unwillingness or inability to correct this situation.” The court noted the local districts’ responsibilities for funding and curricula decisions.

The court stayed its decision for a year, and the plaintiffs settled the case after the state promised $18 million for the 40 schools with the lowest test scores. The Education Law Center says the settlement includes millions for “two-year kindergarten and pre-literacy” programs, remedial instruction for struggling high school students, and other reforms. Alaska’s rural districts also benefited from a 2011 lawsuit settlement that entailed $146 million in funding for rural school facilities. The settlement came after a trial court found that the education-funding system discriminated against Native Alaskan students and violated the Civil Rights Act and the state constitution’s mandate for a school system “open to all children of the state.”

Every state constitution in America requires each respective state to provide an education for school-age children. Many of the “education clauses” require states to offer a “thorough and efficient” or “free” system of education. The Arkansas Constitution, for example, says the state shall “maintain a general, suitable, and efficient system of free public schools and shall adopt all suitable means to secure to the people the advantages and opportunities of education.” The Florida and Washington state Constitutions impose “a paramount duty … to make adequate provision for the education of all children.” Although Montana is unique in explicitly guaranteeing “equality of education opportunity,” many education clauses require a “uniform” system or specify that the state is responsible for students “throughout the state.” The students who sue to enforce these constitutional obligations will have a hard time succeeding if the courts are susceptible to pressure from the executive and legislative branches.

Kansas: Showdown over Dodge City schools

The people of Kansas ratified a constitutional amendment in 1966 that states, “The legislature shall provide for … public schools, educational institutions and related activities.” Suits were later filed against the state on behalf of students, alleging that the state was not satisfying its obligation. In January 2005, the Kansas Supreme Court ruled the state’s education financing system unconstitutional and ordered the legislature to fix it.

The legislature promptly responded with a bill to fix the problem, but the court ruled that the bill actually made it worse. The court said that some provisions of the bill had “the potential to exacerbate inequity” in district funding. The bill allowed all districts to raise more revenue through local property taxes, but “the wealthier districts will be able to generate more funds.” The legislation even allowed districts with higher housing prices to pass a supplemental local tax to fund increased teacher salaries, even though “it is the districts with high-poverty, high at-risk student populations that need additional help in attracting and retaining good teachers.”

The court said these provisions “have the potential to be extremely disequalizing because they … have been designed to benefit a very small number of school districts.” The justices ordered increased funding for schools with more at-risk students in the next school year.

In July 2006, the Kansas Supreme Court deemed constitutional a bill that responded to the 2005 rulings by increasing the budget for education by $755.6 million. The court noted that the bill “materially and fundamentally changed the way K-12 is funded.” One-third of the new funding was directed at educating at-risk students. Funding for special education and bilingual education was increased significantly. The court said that “the legislature responded to our concerns about wealth-based disparities” and dismissed the case.

But the economy soon fell into a recession, and tax revenues plummeted. Gov. Brownback was elected in 2010 on a platform of less government spending and drastically lower income taxes. The legislature failed to deliver the promised increases in school funding, but it passed Brownback’s income tax cut.

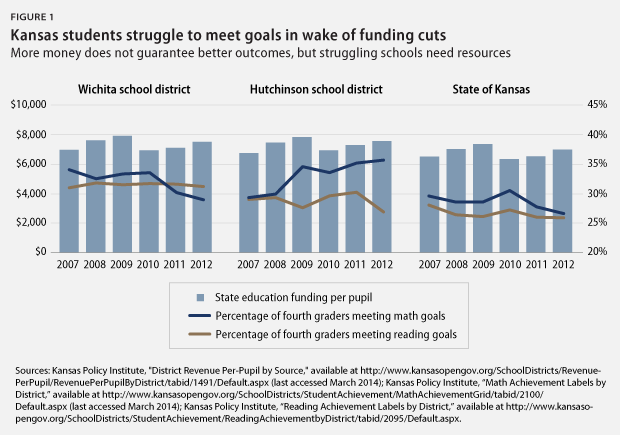

Several poorer school districts filed another lawsuit, alleging that from 2009 to 2012, the state had cut more than half a billion dollars in education funding. This included cuts to special education, school lunches, and funds meant to help property-poor districts. The largest district, Wichita, lost $50 million. Data from the U.S. Department of Education shows that, in the 2009-10 school year, the highest-spending district spent around $9,000 more per student than the lowest-spending district, adjusted for differences in cost of living.

The districts that sued had suffered the most from the budget cuts, and they also happen to have a much higher percentage of non-white students than the state as a whole. Dodge City, for example, is 80 percent Hispanic, and more than half of its students are English-language learners.47 Kansas City is 40 percent Hispanic and 38 percent African American, which the plaintiffs described as “almost a mirror opposite of the rest of the State’s demographics.”

The state appealed to the Kansas Supreme Court, arguing that the trial court had usurped legislative authority. The state said the trial court was:

in effect reordering legislative (and gubernatorial) spending priorities, effectively requiring the Legislature to make cuts in other areas of state government or to raise taxes in order to increase funding for schools.

In their petition to the court, the school districts said the funding cuts caused them to fire employees, reduce teacher salaries, and “make cuts to necessary programs.” Although Kansas had made progress reducing the “achievement gap” between groups of students, the districts warned that the recent cuts jeopardized this progress. In Dodge City schools, more than one-third of African American students did not meet the state’s goal for math in the 2010-11 school year. Three quarters of all Wichita students satisfied the state’s reading goals, but only around two-thirds of poor students and English-language learners achieved the goals. Only 56.6 percent of black students in Wichita satisfied the state’s goals for math.

While the case was pending before the Kansas Supreme Court, Brownback and some Republican legislators vowed to defy any ruling that ordered a specific increase in funding. In his 2014 State of the State address, Brownback told the justices in attendance that “the [state] Constitution empowers the Legislature—the people’s representatives—to fund our schools.” Brownback recently warned that an order for a specific funding increase could lead lawmakers to consider a constitutional amendment to change the way that high court justices are appointed.

Brownback may be alluding to a plan similar to a 2012 bill that removed the “merit selection” commission from the appointment process for the Kansas Court of Appeals. Unlike the process for appointing high court justices, the appointment of appeals court judges is governed by statute, not the state constitution. This bill removed an independent commission that assessed judicial candidates based on their qualifications and instead gave Kansas politicians sole control over nominations to the appellate court. The Republican-controlled state senate in 2013 approved a constitutional amendment to amend the state constitution and remove the court’s power to rule on school financing.

Despite all of this pressure from conservative politicians, the court on March 7, 2014, ruled that the education-funding system violated the state constitution. The court gave the legislature until July 1 to fix the problems. “School districts must have reasonably equal access to substantially similar educational opportunity,” the court decreed. The court found that withholding “equalization funding” for capital projects failed this test and “creates—or perhaps returns the qualifying districts to—an unreasonable, wealth-based inequity.” The court asked the trial court to determine whether the education budget, as a whole, violates the state constitution.

The high court rejected the state’s argument that its ruling infringed legislative authority:

Our Kansas Constitution clearly leaves to the legislature the myriad of choices available to perform its constitutional duty; but when the question becomes whether the legislature has actually performed its duty, that most basic question is left to the courts to answer under our system of checks and balances.

Just days before the ruling, the state senate passed a bill that would fund state courts and restore $2 million in recent cuts, although the funds come with strings attached. The bill also reduces the state supreme court’s authority over budgeting and appointing lower court judges. Legislators included a “non-severability” clause in the courts budget, which means that if the court rules any of the provisions unconstitutional, then the entire bill—including the $2 million in court funding—would be struck down.

Washington state: Judges drawing straws to stay on the bench

In 2011, the Democratic governor of Washington state signed a budget that eliminated $1.8 billion in education funding. Salaries were slashed. Schools were forced to cut their budgets for student transportation. One superintendent said that, after a school cut bus transportation for students living within a mile, “an elementary-age student … who otherwise would have been transported by bus, walked to school across a highway and was struck by a car.”

These cuts came on top of an already underfunded system. A study of the 2006–07 school year education budget found that, due to insufficient funding for textbooks, “Only five percent of K-5 students could obtain an up-to-date math curriculum from the State.”

A lawsuit was filed alleging that the 2011 budget violated the state constitution, which states that “It is the paramount duty of the state to make ample provision for the education of all children residing within its borders.” The Washington Supreme Court in 1978 interpreted this mandate to mean that school districts could not be forced to rely on temporary local taxes, instead of state funding, to pay for basic education costs. Funding schools by local taxes means that property-poor districts have fewer resources. The court largely left it to the legislature “to select the means of discharging” its constitutional duty to fund education.

By the time the lawsuit over the 2011 budget reached the state supreme court, however, the justices appeared tired of waiting for legislators to live up to their constitutional responsibilities. “What we have learned from experience is that this court cannot stand on the sidelines and hope the State meets its constitutional mandate to amply fund education,” the court said. “This court cannot idly stand by as the legislature makes unfulfilled promises for reform.”

Decades after the court first ruled the education-funding system unconstitutional, the executive and legislative branches had still not remedied the deficiencies. “If the State’s funding formulas provide only a portion of what it actually costs a school to pay its teachers, get kids to school, and keep the lights on, then the legislature cannot maintain that it is fully funding basic education.” In the 2010-11 school year, the highest-spending district in Washington spent almost $16,000 more per student than the lowest-spending district—a wider disparity than in more than 40 other states. The court noted a “promising” reform initiative in progress, but it maintained jurisdiction over the case to monitor its implementation.

Conservative legislators responded in 2013 by introducing a bill that would shrink the court from nine justices to five justices and require the justices to draw straws to keep their seats on the bench. The bill states that “the positions of the four judges … drawing the shortest straws shall be terminated.” State Sen. Michael Baumgartner (R), a critic of the court’s education cases, introduced this bill and another bill in 2014 to eliminate two positions on the court through attrition as the justices retire. Baumgartner said the bills were “a punch-back to the supreme court overreaching its constitutional role on writing the budget.” He described the bills as saving the state money, which would be used to comply with the education mandate. Neither bill has received a vote.

The 2014 bill came just after the court issued a rebuke to the legislature to speed up its implementation of the 2012 order for more funds. In an order issued on January 9, 2014, the court noted “meaningful steps” by the legislature but said “it cannot realistically claim to have made significant progress” in fulfilling its constitutional responsibility. The court faulted the legislature for inadequate teacher salaries and insufficient funding for supplies and capital improvements.

On February 14, 2014, Baumgartner introduced yet another bill targeting the state supreme court. This bill would require the court to increase the number of decisions it issues by 50 percent. One Washington state news outlet, Crosscut, said the “bill reads like a tit-for-tat measure” and noted that it includes language that appeared in the court’s 2014 order. The bill orders the court to “draw upon its purported budgetary expertise” and provide a timetable for implementing a plan to increase productivity by April 30, 2014, the same deadline the court imposed for a progress update on education funding.

State Sen. Christine Rolfes (D) criticized Baumgartner’s proposals for “not moving anything forward.” Rolfes said she is worried about “more subtle” pushback, in the form of the state senate “dragging its feet.” The state legislature recently adjourned for this session without agreeing on a bill to fix Washington’s schools. Rolfes said she worries that the Republican majority in the Senate is “trying to provoke a constitutional crisis” by defying the court.

New Jersey: Gov. Christie looks to pack “activist” court with his judges

The New Jersey Constitution requires the state government to offer a “thorough and efficient” education for all of the state’s school-age children. The New Jersey Supreme Court ruled in 1973 that this obligation was not satisfied by a school-funding system that relied primarily on local property tax revenue. As in Washington and Kansas, the court found that this system discriminated against students in urban districts with fewer resources. The court and the legislature went back and forth for decades, with the court eventually ordering more funding from the state for the poorer districts. Conservative politicians criticized the court for “activism,” but by 2009, the legislature had passed a bill that the court deemed constitutional. The court lifted all of its orders on education funding, releasing the state from decades of judicial oversight.

But when Gov. Chris Christie (R) took office in 2010, his first budget slashed funding for education, including the urban districts for which the court had previously ordered more resources. The court ruled that these cuts violated the state constitution, and it reimposed its remedial order for more funding for the poorer schools. The court described the cuts as a “real, substantial, and consequential blow to the right to the achievement of a thorough and efficient system of education.”

Christie responded by arguing that the court should not “determine what programs the state should and should not be funding,” despite the language in the state constitution. Christie campaigned against the court for “legislating from the bench” and pledged to “reshape” the court. In an unprecedented power grab, Christie in 2010 threw a respected justice off the bench by denying him tenure. A recent Center for American Progress report stated:

Every governor before Christie—even a Republican governor who served as his mentor—did not view the executive appointment power in this way. Christie’s attempts to make the court more conservative ran afoul of traditions that have ensured the high court’s independence from the political branches of government since the ratification of the state constitution. Until now, the political branches renominated every sitting justice for tenure, regardless of whether they agreed with the justice’s rulings, and maintained a partisan balance in which neither Republicans nor Democrats had more than a 4-3 majority on the court. … Christie is trying to change all of this. He wants a conservative court that will rule in his favor and against middle-class families and poor school districts.

The Democrat-controlled New Jersey State Senate has resisted Christie’s effort by refusing to confirm some of his nominees.1 Chief Justice Stuart Rabner has filled the vacant seats by appointing lower court judges, but the chief justice is up for tenure in June.

Alaska: Leaving some students out in the cold

When Alaska became a state, each student attended one of two school systems—one operated by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs for Native Alaskan students or one operated by the state for non-Native Alaskan students. The new state adopted a constitution that required the legislature to maintain “a system of public schools open to all children of the state.”

As discussed above, a group of mostly Native Alaskan school districts and students sued the state in 2004, but they settled the case after the state promised $18 million for the lowest-performing schools.1 A 2011 lawsuit settlement led to more funding for rural school facilities.

A new lawsuit, however, alleges that the state is not spending enough money on nonrural school facilities that are located in the state’s “boroughs,” rather than in unincorporated, rural areas. Boroughs in Alaska contribute some of the costs for educating their students, but unincorporated communities do not. This lawsuit alleges that, by requiring Ketchikan Borough to pick up part of the tab for education, the state is not providing an adequate education to students in Ketchikan.

Gov. Sean Parnell (R) responded by warning that “if Ketchikan is the driving force behind a lawsuit that could result in more financial exposure to the state, legislators and I view [budgetary] requests from Ketchikan through that lens.” Parnell said, “It just really made it easy for legislators to say no to Ketchikan’s projects.”

Regardless of whether students in the boroughs are being unconstitutionally shortchanged, a threat to use fiscal appropriations to punish a school district for filing a lawsuit sets a dangerous precedent. If the same threat had been made to the mostly Native Alaskan districts in the earlier lawsuits, the plaintiffs may have felt pressure to back off. Parnell quickly backtracked in the face of criticism and pledged “fairness and equity” in appropriations. But he noted that there are many state legislators “who will be making those kinds of decisions as well.”

Parnell supports a constitutional amendment in Alaska that would roll back the state supreme court’s authority over education funding in one area: school vouchers. When Alaskans required an education for all students in its constitution, they included the mandates that schools “shall be free from sectarian control. No money shall be paid from public funds for the direct benefit of any religious or other private educational institution.”

In 1979, the Alaska Supreme Court interpreted this to mean that the state could not award grants to students for tuition at private colleges. The court reasoned that the student “is merely a conduit for the transmission of state funds to private colleges.” The court noted that voters had rejected an initiative just a few years earlier to repeal the constitutional provisions at issue.

Now, Alaska Republicans are trying again. The legislature is considering an amendment that would allow voucher programs to move forward. Dick Komer, an attorney for the pro-voucher Institute for Justice, said the court’s 1979 ruling “clearly went too far” and voiced support for an amendment to overturn it.

The sponsor of the constitutional amendment claims that polls show massive support for the amendment, but citizens speaking at a recent public forum overwhelmingly opposed school vouchers. One Alaskan said, “Public dollars should be used for public schools and should not be diverted to unaccountable private, sectarian, and religious schools.” A representative of the local NAACP warned that the amendment “will promote education as a private commodity rather than a public endeavor.”

Conclusion

School systems in America get much of their funding through local property tax revenue. These systems leave more funding for school districts with more valuable property and less for districts without as much property tax revenue. Most state governments try to equalize education with state funding, but state legislators will naturally favor the school districts that they represent and those with political power. When courts force legislatures to comply with the respective state constitutions, some state legislators respond by threatening judicial independence.

Courts must be free from political pressure so they can check the authority of the executive and legislative branches. The disparities in states such as Washington and New Jersey prove that poor school districts are shortchanged in the political process and cannot expect legislators to protect their rights to an adequate education. This means that state supreme courts are the only institutions that can enforce the legislatures’ constitutional responsibilities to provide an education for all students. If the courts cannot demand that legislators live up to their constitutional obligations, no one can. The mandate to provide an adequate education means nothing if there is no institution besides the legislature to define this obligation.

There are currently 11 lawsuits over inequitable school funding pending in state courts. “Over the years, all but five states have been the subjects of such lawsuits,” according to Stateline, the news service for the Pew Charitable Trusts. The focus of these lawsuits are shifting, now that plaintiffs have statistical data that show unequal outcomes in education. One lawsuit in Michigan, for example, seeks to enforce a statute that says that all third-grade students must learn to read. The Center for American Progress said in December 2013 that this lawsuit could be “the latest in a string of cases … advancing arguments about equity in the delivery of education, rather than just the financing of education.”

As these arguments wind their way through state courts, advocates for education-funding equality must act to protect judicial independence. Many parents and teachers in these states have not hesitated to let their legislatures know the importance of education funding and reform. They should also demand that their legislators respect judicial independence and stop attacks on courts that order states to improve schools. Students in poor districts should be able to turn to courts for justice without worrying about whether politicians will pressure judges to rule for the state.

Billy Corriher is the Director of Research for Legal Progress at the Center for American Progress.