“America is a nation of builders,” President Donald Trump declared in his first State of the Union address in January, touting his commitment to infrastructure.1 But the White House’s proposal released in February would do little to build and improve infrastructure. In fact, it would harm communities by undermining their hard-won rights to help shape federal infrastructure decisions.

The administration’s plan would cannibalize existing federal funding streams, increase the burden on states, and take a hammer to a suite of bedrock environmental laws, including the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act, which work to protect communities from harmful pollution.2 But the plan would do the most damage to a lesser-known statute: the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

NEPA was enacted to ensure that both the views of the public and environmental considerations are taken into account when building infrastructure. The law has long been a bugbear for conservatives who put the blame on NEPA for delays in building infrastructure, even though less than 1 percent of projects require a full environmental impact statement—the most stringent and resource-intensive form of NEPA analysis.3

For NEPA, the Trump administration’s infrastructure proposal would be death by a thousand cuts. The administration proposes exempting even more projects from federal review by expanding so-called categorical exclusions and putting a hard stop on the amount of time agencies have to conduct NEPA reviews. Perhaps most damaging of all, the Trump administration wants to make it virtually impossible for the public to challenge potentially harmful permitting decisions through reducing the statute of limitations for such challenges to just 150 days. Taken together, these attacks on NEPA would render the statute toothless.4

However, there is no need to speculate about the serious harm that could be done to American communities and our environment if the Trump administration succeeds in their push to eviscerate NEPA. All one needs to do is look to relatively recent history.

By the time NEPA was signed into law in 1970, local authorities had spent decades using federal infrastructure dollars to create or enforce racial segregation. “By the mid-twentieth century, ‘slums’ and ‘blight’ were widely understood euphemisms for African American neighborhoods,” writes Economic Policy Institute researcher Richard Rothstein in his 2017 book, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, which explores the multiple policy levers that federal, state, and local governments used to segregate American communities.5 “In many cases, state and local governments, with federal acquiescence, designed interstate highway routes to destroy African American communities,” Rothstein writes. “Highway planners did not hide their racial motivations.”

Rothstein is not being hyperbolic. In cities across the country, federal infrastructure dollars were used to bulldoze and evict communities of color and low-income families and to erect literal barriers to jobs and economic opportunity. Millions of Americans are still living with the consequences of these decades-old decisions, including through significantly increased exposure to harmful air pollution. In 2010, disparities in exposure to just one harmful pollutant found in transportation emissions were larger by race and ethnicity than by income, age, or education, with people of color experiencing 37 percent higher exposure than whites, according to a recent study from the University of Washington.6

Since NEPA was signed into law, the federal government has essentially been required to show its work to the public—to clearly justify its plans for building infrastructure and to carefully consider alternatives; the public, in turn, has been able to participate transparently in the process. “Public participation has in many cases made a real difference,” according to a 2010 report by the Environmental Law Institute looking back at four decades of NEPA.7 “In numerous cases, portions of or entire NEPA alternatives proposed by individuals, municipalities, tribes, organizations and others have been selected by federal agencies as a result of the NEPA review.” It is this public power that the Trump administration’s proposal would strip away.

This issue brief reviews how three American communities were badly damaged or destroyed by federal infrastructure projects in the days before NEPA.

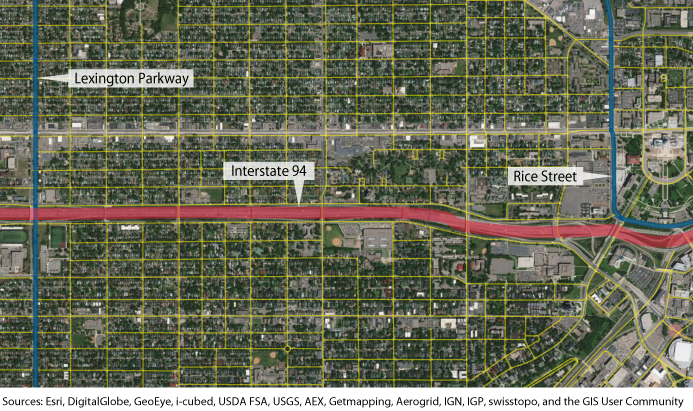

St. Paul, Minnesota: I-94

From the time it was first settled in the 1850s, St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood was a diverse place—first as a home to immigrants and later to black Americans. By the 1930s, half of St. Paul’s black population lived in Rondo, and the neighborhood was home to a thriving arts scene, integrated schools, and the St. Paul chapter of the NAACP.8 “Even during the Jim Crow era, blacks and whites mixed relatively freely; interracial dating and even marriage sometimes took place” in Rondo, according to MNopedia, a project of the Minnesota Historical Society.9

Interstate 94 (I-94) changed all of that. Conceived after World War II to link the downtowns of Minneapolis and St. Paul, I-94 cut directly through the heart of Rondo. After the Federal-Aid Highway Act passed in 1956, sending funds for highway construction to municipalities across the country, local leaders in the black community created the Rondo-St. Anthony Improvement Association to fight against the highway plan.10 But, lacking both political power and legal recourse to challenge the route, the group’s options were limited.

The Federal-Aid Highway Act had authorized the secretary of commerce “to acquire, enter upon, and take possession of such lands or interest in lands by purchase, donation, condemnation, or otherwise” if states requested the federal government’s assistance in arranging rights-of-way planned highways.11 When construction on I-94 began in 1956, one of the Rondo community leaders who opposed the route, the Rev. George Davis, refused to leave his home. He was forcibly evicted, his house damaged by police with sledgehammers, as his family watched. “They were knocking holes in the walls, breaking the windows, tearing up the plumbing—just to make sure he didn’t try to move back in there,” his grandson, Nathaniel Khaliq, recalled to Minnesota Public Radio in 2010.12 Khaliq was 13 years old when I-94 was built.

Some 650 families saw their houses bulldozed alongside Davis’ to make way for I-94.13 Nearly 100 mostly black-owned businesses, from grocery stores to restaurants, that used to dot the neighborhood are remembered on a map of historic Rondo compiled by the Remembering Rondo project.14 All were wiped out to make way for the highway.

In 2015, both the mayor of St. Paul and the head of the Minnesota Department of Transportation, Charles Zelle, did something virtually unprecedented: They apologized.15 “We would never, we could never, build that kind of atrocity today,” Zelle said.

One of the reasons I-94 could not be built in the same way today—scattering hundreds of families and destroying a neighborhood—is because NEPA contains far stronger requirements for public consultation than any prior infrastructure law. NEPA would have given the Rondo-St. Anthony Improvement Association a fighting chance to save their community—a place where civic spirit and pride was so strong that, decades later, the nonprofit Rondo Avenue Inc. still holds an annual Rondo Days festival to celebrate the neighborhood’s legacy.16 In fact, ReConnect Rondo, a community nonprofit organization, is working on a proposal to build a land bridge over I-94 to literally knit the neighborhood back together again.17

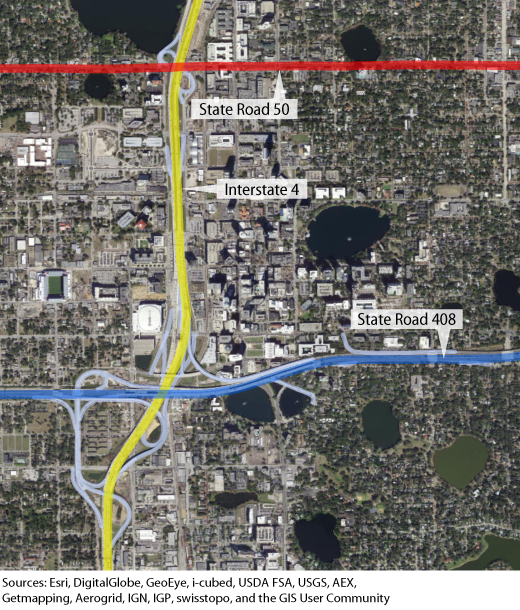

Orlando, Florida: I-4 and State Road 408

Griffin Park, a federal housing project in the Parramore neighborhood of Orlando, is surrounded on all sides by elevated highways. “From above, you see a grid of apartment buildings encircled menacingly within a loop of the interchange, as if inside a noose,” HuffPost’s Julia Craven wrote earlier this year in an article examining the serious air-quality and respiratory-health issues facing the neighborhood’s residents.18

In the late 1950s, Interstate 4 (I-4) was the first of those highways to be built. In the white, middle-class Orlando suburb of Winter Park, residents successfully pressured state and federal government officials to keep the interstate from cutting directly through their downtown.19 The Parramore neighborhood, which was and remains predominantly black, was not so fortunate, as the elevated highway severed a number of local roads that had previously connected Parramore to downtown Orlando. “As a result, from the 1970s to the 1980s, Parramore suffered visible impoverishment while downtown [Orlando] improved,” according to Yuri Gama, a researcher studying Parramore.20 Today, the median household income in Parramore is just $13,613, and 7 in 10 children live below the poverty line.21

In the mid-1960s, planning began for an east-west highway to complement the north-south I-4. Two routes were proposed: one paralleling Colonial Drive, and one about a mile south, straight through the heart of the Parramore district. The second option for State Road 408 was selected in 1969, just a year before NEPA became law—in part, because the right-of-way costs for acquiring and demolishing 1,100 homes, 80 businesses, and six churches in that neighborhood were estimated to be less than the costs associated with the first proposed route.22 As a result, the community was further carved up by impassible high-speed expressways—and the Griffin Park housing project was trapped completely.23

While cost is an important consideration in building infrastructure, it should not be the sole determining factor. Infrastructure should serve the entirety of a community and a local economy—it should not evict, isolate, and poison marginalized communities. Had State Road 408 been planned after the passage of NEPA, the law’s requirements to consider environmental, health, and safety issues may well have prompted highway planners to choose the alternate route a mile north of Griffin Park. As it stands, in 2006, Orlando’s city government acknowledged that the location of State Road 408 and the interchanges along it “exacerbated I-4’s impact” on Parramore.24

New Haven, Connecticut: Oak Street Connector

Before its demolition, the Oak Street neighborhood in New Haven, Connecticut, was a dense hodgepodge of races and ethnicities—a place where recent immigrants from Eastern Europe lived alongside black Americans and families of Italian descent. Like St. Paul’s Rondo, the former residents of Oak Street and its environs have gathered regularly for decades to reminisce and reflect. “It was a sacred spot. … A world. A universe,” one former resident recalled in 2000.25 “It was alive, it was exciting, it was always uplifting, and we all felt that it belonged to us,” another said at the same event.

City officials saw it differently. Richard C. Lee, New Haven’s mayor from 1954 to 1970—and one of the nation’s most aggressive pursuers of “urban renewal” projects—called the neighborhood “a hard core of cancer which had to be removed.”26 The New Haven Redevelopment Agency called Oak Street a “slum” and wrote in 1955, “Not every structure in this area is substandard, but like cutting a rotten spot from an apple, some of the good has to be cut away too to save the whole.”27

When the bulldozers came in 1956, more than 3,000 people and 350 small businesses lost their homes.28 In their place, the city built one out of a planned 10 miles of highway running from Interstate 95 (I-95) into the heart of New Haven, dead-ending in a parking garage.29 The six-lane highway divides the city, with the main campus of Yale University and most of downtown New Haven on one side, and The Hill—one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods and the place to which many displaced Oak Street residents moved—on the other.

Coverage of recent initiatives to repair the damage done to New Haven by the Oak Street Connector paper over this history. A 2012 New York Times article on a proposal for revitalizing the area made no mention of the massive displacement that made way for the Oak Street Connector, dryly observing, “[W]hat seemed like a good idea at the time is now considered by many to have been a big mistake.”30

Had NEPA been in place, the residents of Oak Street may have been able to advocate for a less destructive alternative to the Oak Street Connector—as in fact happened in another, more politically connected part of New Haven. The state of Connecticut had plans for a highway cutting straight through the heart of Wooster Square, which, like Oak Street, was home to a diverse panoply of residents. A Catholic priest in the neighborhood organized residents to lobby the mayor against the highway plan, and the group was “brought in by [Mayor] Lee to help plan a renewal effort that eventually included rehabbing hundreds of buildings, planting trees along the streets, creating small parks, and constructing a few clusters of low-rise housing.”31 Wooster Square—and its two iconic pizzerias, covered glowingly today by food and travel reporters—survived.32

Having first provided the funds through the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act to plow Oak Street into the ground, the federal government is now supporting the Downtown Crossing project to enable pedestrian access, slow down the speeding highway traffic, bring back street-level retail, and “re-stitch the daily life of the city back together.”33

Conclusion

St. Paul, Orlando, and New Haven are only three examples of dozens across the country where an influx of federal infrastructure dollars, without strong requirements for public engagement or environmental protection, enabled local leaders to evict low-income families and communities of color and attempt to eradicate entire neighborhoods.

In Miami, state officials chose a route for I-95 in 1956 that cut directly through the city’s largest predominantly African-American neighborhood, even though there were other, less disruptive options at hand. “An alternative route utilizing an abandoned railway right of way was rejected, although it would have resulted in little population removal,” Rothstein writes in The Color of Law. “When the highway was completed in the mid-1960s, it had reduced a community of 40,000 African-Americans to 8,000.”34

In Nashville, Tennessee, as in Rondo, local leaders tried to fight back against the construction of Interstate 40, which cut through the black business district and buried beneath its concrete pylons venues where Little Richard and Jimi Hendrix got their start.35 They managed to get a lawsuit arguing for a route change all the way to the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals—where it was rejected, in part, because city officials had met the minimum standards for public notification in the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act, which fell far short of NEPA’s requirements for public consultation.36

These kinds of stories are not solely relegated to the past. The state of Indiana is proposing widening a highway that cuts through downtown Indianapolis, affecting eight historic neighborhoods.37 The city’s mayor and local leaders have objected to the plan, putting forward alternatives that would both ease congestion and better integrate the highway into the city’s landscape.38 Because of NEPA and other protections, the city has a fighting chance to stop the state from undermining recent efforts to increase public transit and revitalize Indianapolis neighborhoods that were harmed by the initial construction of the highway decades ago.

NEPA should not be seen as a hurdle or a barrier to building infrastructure—it should be embraced by the state, local, and federal government and by project developers as an opportunity to design and construct projects that strengthen local communities. The NEPA process undertaken in the design of a light rail extension in Charlotte, North Carolina, for instance, resulted in measures to increase public safety and decrease noise pollution in residential areas.39

The Trump administration’s proposal would pave the way for hastily and thoughtlessly designed projects. Four days after taking office, President Trump signed an executive order aimed at expediting environmental reviews, arguing that, “Too often, infrastructure projects in the United States have been routinely and excessively delayed by agency processes and procedures.”40 Since then, his administration has routinely repeated this dangerous argument, advocating for new legislation to move projects more quickly at the expense of the public’s voice in the process, while ignoring tools Congress has already made available to expedite infrastructure permits by, for instance, improving coordination between multiple federal agencies.41

“[B]eyond the easy rhetoric of ‘better, faster, cheaper’ lies an ugly reality of poorly conceived projects that produce long-lasting harms and ultimately cost our society and economy far more than any modest upfront savings,” Center for American Progress Director of Infrastructure Policy Kevin DeGood noted earlier this year.42 The Trump administration should heed the lessons of Rondo, Parramore, and Oak Street, and stop pursuing their reckless infrastructure plan.

Kristina Costa is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. Lia Cattaneo is a research associate for Energy and Environment Policy at the Center. Danielle Schultz is an intern with the Energy and Environment team at the Center.