As it works on the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act (HEA) of 1965, Congress is considering changing the way the federal government holds colleges accountable by measuring performance program-by-program rather than institution-by-institution, as it does today. On the surface, this idea has common-sense appeal because a college could, for example, have a high-performing nursing program but also a disastrous engineering program. Rather than judging an institution by its overall performance—as is the case with current accountability metrics—program-level accountability would judge each program at a school in isolation. This means that if some programs did well and others did poorly, only the poorly performing programs would face sanctions.

Beneath the surface, however, there is a major catch to this approach. A program-level accountability system would run the risk of papering over the outcomes of a large fraction of students because the number of students in many programs is too small to allow for stable measurements of the programs’ performance. Worse still, program-level measurements would also make it very difficult to hold institutions accountable for their performance with subgroups of students of color because an even larger share of programs have too few students of color to fairly judge these groups’ individual outcomes. As a consequence, sizable portions of college students would be in programs whose performance would be impossible to judge. Based on some basic assumptions about how program-level accountability would operate, roughly one-third of black and Hispanic students could be left out of its measures, along with 4 in 10 Asian students. This means that lawmakers may have to choose between a program-level accountability system and a system that holds institutions accountable for how they serve students of color.

Between the House Committee on Education and the Workforce’s reauthorization bill—the Promoting Real Opportunity, Success, and Prosperity through Education Reform (PROSPER) Act—and the recent white paper released by Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-TN), chairman of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, enthusiasm for program-level accountability is high among Republican lawmakers. Given the wide variation in different majors’ earning potential, the desire to ensure that an institution’s average performance doesn’t hide poor performance within certain majors is understandable. But the value of a program-level approach must be weighed against the consequences of moving to such a system. Because there are wide gaps in college access, completion, and repayment across racial groups, any change to the higher education accountability framework should prioritize accountability for the outcomes of students of color over accountability at the program level.

Small program sizes make it difficult to protect all students

Key to any accountability measure is its ability to accurately reflect the underlying reality at an institution. Drawing conclusions from the outcomes of very few students can render any measure unreliable. In such situations, the outcome of a single student can have a significant impact on whether a school faces sanctions from the government—the forms of which will be determined during the HEA reauthorization process. For this reason, the College Scorecard combines data across several years when there are fewer than 30 or 50 students in a group for a single year, depending on what it is measuring. For example, the U.S. Department of Education requires that there be at least 30 completers for a gainful employment program to be measured.

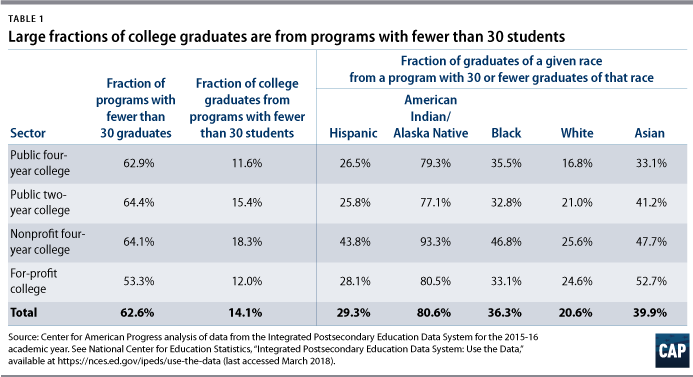

A new program-level accountability system would also likely exclude programs with too few students. To test how widespread this problem is, let’s examine the fraction of programs that had fewer than 30 graduates in 2016. (see Table 1) Overall, 62 percent of programs had fewer than 30 graduates in 2016. Those programs are by definition very small, but they add up to about 14 percent of graduates that year. That means that the outcomes of well more than 1 in 10 graduates would not be measured by a program-level accountability system that excluded programs with fewer than 30 students.*

Program-level accountability would miss even larger swathes of graduates who make up racial subgroups. As Table 1 shows, the outcomes of 29 percent or more of Hispanic, black, and Asian graduates would remain hidden in such a system. At the most extreme end, about 80 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native graduates attended schools that could not be held accountable for their performance due to the small number of such students at programs throughout the country.

Combining data across years does not solve the problem

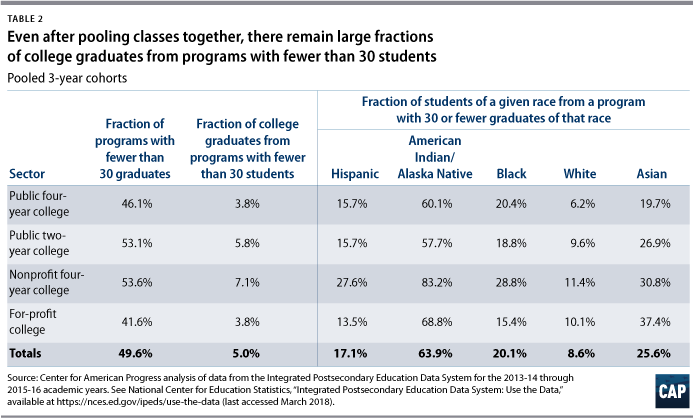

Because both the College Scorecard and gainful employment rule combine data for students in different years when the number of students at a school is low—an effort to make the measurements more reliable—lawmakers might be tempted to take the same approach in the Higher Education Act. As Table 2 shows, expanding the measure to three years of graduates would still leave a large percentage of graduates unprotected. Even when combining three years of graduates, about 17 percent of Hispanic students and 20 percent of black students graduated from a program with fewer than 30 graduates.

Congress will likely have to choose between program-level accountability or accountability for schools’ performance with students of different racial groups. At the very least, these practical considerations deserve more thought from legislators interested in program-level accountability. Given the many worrying race-based gaps in college outcomes, any insights that may be gained by understanding program-level outcomes are likely outweighed by the consequent inability to measure outcomes by race.

If in the final accounting it comes down to a choice, ensuring that the U.S. higher education system has accountability for students of color is more important than program-level accountability.

To learn more about or replicate our findings, you can find our detailed Stata code here.

CJ Libassi is a policy analyst for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress.

*Author’s note: These program sizes would likely be somewhat bigger if they included all students who enroll in a program and not just the graduates, but it is not clear whether a final program-level accountability system would apply to all students or just graduates. Even if it did apply to all students, many students drop out before declaring a major, making it hard to know if and how such students would be counted. Finally, working against the possibility that using completers could overstate the number of small programs is the fact that this analysis focuses on all completers, not just those who borrow money to go to school. Any loan-based accountability structure would be focused only on those students with loans, meaning that the above numbers likely overstate the fraction of borrowers in programs with more than 30 students. Additionally, because the data counts the number of degrees awarded in each program rather than the number of students awarded those degrees, these estimates may be overly generous by giving programs credit when one student gets multiple degrees.