Introduction and summary

By 1992, the U.S. Congress was fed up with higher education accreditors—the watchdogs tasked with determining whether colleges deserve access to federal financial aid dollars. Congress believed accreditors were getting too closely entangled with the schools they were supposed to oversee,1 at a time when the national student loan default rate exceeded 22 percent.2 One particularly galling example occurred in 1991, when two accreditors merged with the trade association that lobbied on behalf of private, for-profit career schools.3 Accreditors also appeared to allow egregious behavior, such as when an agency allowed a beauty school to extend accreditation to programs in aviation mechanics and air-conditioning repair without additional oversight.4

So, Congress acted. In the 1992 reauthorization of the Higher Education Act (HEA), lawmakers laid out a number of new requirements for accreditation agencies.5 The HEA created a process and set of standards for federal review and approval of accreditors; required these agencies to consider student outcomes at institutions; and delineated the areas where accreditors had to have standards.6

The new law also included steps to make accreditors more independent and less beholden to schools. Congress banned close relationships between accreditors and trade associations by requiring accrediting agencies to be separate and independent. It also required accreditors’ governance boards to include representatives of the general public, hereafter referred to as “public commissioners.”7

Coming amid other changes to root out conflicts of interest, the public commissioner requirement sought to make accreditation governing boards, or commissions, less insular. It intended to bring more independent and public voices to the commissions that have the ultimate say on which institutions can obtain accreditation and thus access federal financial aid. The public commissioner role also aimed to provide an outside perspective from that of other commission members, who by and large came from institutions overseen by the accreditor. This role was designed to identify issues that individuals with backgrounds exclusively in higher education might miss and to ensure that the accreditation system would not entirely be based on educators policing one another.

More than a quarter-century later, there are distinct differences in how well agencies use their public commissioner spots to provide truly independent voices. Several agencies have public commissioners who bring in useful outside expertise—commissioners such as lawyers, accountants, or consultants with decades of experience in business-related disciplines where institutional representation may not be as strong. However, a Center for American Progress review of public commissioners as of January 2019 finds that six of the 14 main accreditation agencies have more than one individual serving in these positions with direct links to colleges, suggesting that they lack the necessary independence that a public commissioner should bring. This is not to suggest that these public commissioners lack useful qualifications or that the agencies are violating existing requirements for these individuals. Rather, these findings expose the weaknesses in the definition of public commissioners that Congress should address in the HEA or that the U.S. Department of Education should fix through regulation. For example, one accreditor recently had serving on its board two public commissioners who run college trade associations, which represent and have lobbied on behalf of private nonprofit colleges in states that the agency oversees. (Note: These two individuals from trade associations were not on the commission as of March 2019 because their terms had expired.) Neither person violated the current public commissioner definition—which bars only individuals who are directly employed by a college—as these individuals work for a nonprofit organization whose funding happens to come from dues paid by multiple institutions.

More commonly, many of these six accreditation agencies fill their public commissioner slots with retired academics or college administrators. The HEA intentionally created a commissioner category distinct from the institutional representatives that comprise most of an accreditor’s commission. Relying heavily on current or former academics and administrators to fill public commissioner spots undercuts the independence and outside perspective these individuals should bring. It suggests that the public commissioner requirement is too often treated as a compliance exercise rather than an opportunity to bring different voices to the accreditation decision-making process.

A longtime school executive may know the ins and outs of accreditation but may not be capable of effectively channeling the public interest.

Some instances particularly highlight how accreditors seem to treat the public commissioner requirement as necessitating minimal distinctions from institutional representatives. For example, at one accreditor, an institutional representative became a public commissioner just one year after retiring. In another case, a multidecade school owner served as a public commissioner on the same commission that used to approve their institution.

Overall, CAP finds that of the 69 public commissioners on accrediting commissions as of January 2019, 22 have backgrounds that are more closely aligned with institutions than with the general public. The bulk of these 22 individuals are now retired, but were administrators at institutions approved by the very agency for which they now work as a commissioner. This includes 12 of 38 public commissioners at accreditors that represent most public and private nonprofit colleges and 10 of 31 public commissioners at agencies that mostly oversee for-profit and technical colleges. This would be similar to filling a college’s board only with former presidents, deans, and provosts from that institution.

These results clearly demonstrate that the current federal definition of a public commissioner is inadequate. The value of a public commissioner is to represent the general public’s interest. A longtime school executive may know the ins and outs of accreditation but may not be capable of effectively channeling the public interest.

This report recommends strengthening the federal definition of a public commissioner through either the HEA or regulation to better reflect the goal of bringing into the accreditation system individuals who have independent backgrounds. For many agencies, changes to the definition would simply reinforce best practices and require minimal to no changes in their chosen public commissioners. However, for others, these fixes would ensure that slots for public commissioners go to people with backgrounds that are less aligned with the institutions they are meant to oversee.

In particular, the improved definition should:

- Prevent newly retired administrators or professors from holding public commissioner positions. All public commissioners should not have worked primarily in higher education for at least 10 years. This time limit should also apply to anyone who has owned equity in an institution of higher education.

- Stop individuals who previously represented schools on commissions from serving as public commissioners. Anyone who has served as an institutional representative on a commission would be prevented from serving as a public commissioner with any accreditor.

- Address broader conflicts of interest. The definition should expand the ban on what constitutes employment connected to an institution so that it includes individuals who have any association with higher education institutions or organizations—such as working at a college trade association—not just those affiliated with the accrediting agency.

Public commissioners also need resources for professional development. This support can help public commissioners get up to speed faster and identify areas where the public has a greater interest, such as making accreditors more transparent or placing a greater emphasis on college outcomes. To that end, there should be professional development resources that can bring public commissioners together across agencies in settings that do not involve institutional or accreditor representatives. This should be done by a private organization independent of accreditors and institutions of higher education to avoid conflicts of interest. If necessary, Congress could appropriate funds for a program to competitively select the organization that provides this training.

Improving the public commissioner role should be the starting point of making accreditor decision-making bodies more inclusive of other voices who are invested in higher education outcomes. This process should include other constituencies, such as students and states. The idea is not to replace the bedrock principle of accreditation as a system that largely relies on peer review, but rather to recognize that a fuller picture of the parties affected by higher education will result in a stronger and more considered process.

Accreditation, commissioners, and public commissioners

Under federal law, institutions wishing to participate in federal financial aid programs must obtain accreditation from an agency that has been recognized by the Education Department. Despite their federal role, accreditation agencies are private, independent membership organizations that receive no direct government support.

This report focuses on two types of accreditors: regional and national. Currently, regional accreditors only approve schools within a defined geographic area, though the Trump administration is proposing tweaks to existing regulations that would make these boundaries more flexible.8 There are seven of these regional agencies across the country. For instance, any college seeking regional accreditation in Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, or Washington, D.C., currently must go to the Middle States Commission on Higher Education for accreditation. A school in Connecticut, meanwhile, can currently only obtain regional accreditation from the New England Commission of Higher Education (NECHE). Most public and private nonprofit institutions have regional accreditation.

National accreditors, on the other hand, consider colleges in any part of the country. However, instead of limiting their oversight by geography, they often approve only certain types of institutions based on the types of programs offered. For example, some national accreditors will only approve schools that offer career-oriented programs; another only reviews institutions that offer health-related programs; while another only accredits beauty schools. National accreditors mostly, but not exclusively, accredit private for-profit colleges.

The accreditation process and commissioners’ roles

Accreditation is a system of peer review. The process starts with an institution preparing a self-study that explains how well it meets an accreditor’s standards, which it then sends to the accreditation agency. The agency reviews the self-study and follows up with a site visit from a team of external experts, as well as at least one representative from the accreditation agency. These experts are a combination of academics; college administrators; people who work in a field for which an institution provides training, such as a nurse visiting a health-focused school; or an employer. They are chosen by the accreditation agency but are not employees and typically receive no compensation besides reimbursement for travel expenses and meals. The experts review the school and make their own recommendations about whether an institution does or does not meet the agency’s requirements.

The ultimate arbiters of whether an institution merits accreditation, however, are the agency’s commissioners. These individuals are the appointed board of directors of an accreditation agency. They meet a couple times each year and vote on whether individual institutions should receive accreditation or continue to be accredited. Commissioners also decide whether to sanction institutions that are not meeting standards. Their work is informed by what the site team visit uncovers but is not necessarily bound by those findings.

Commissioners are therefore at the center of the important work of safeguarding the billions of taxpayer dollars that colleges collect through students’ federal financial aid awards. They are the only outside voice with a deciding role in the choices these agencies make, which in turn affects the flow of tens of billions of dollars in federal financial aid each year. Most other commissioners have direct relationships with an institution that the accreditor oversees, while states, the federal government, and students do not have any representation. Public commissioners are, in short, the only bulwark against a system that is by design based on insularity and self-assessment. Because they do not work for a higher education institution, these individuals should be freer to push ideas that might be more unpopular with other commissioners, such as greater transparency or a more explicit focus on student outcomes.

Because key accreditation decisions are mostly made by representatives of the schools they oversee, federal law also requires each agency to have a conflict of interest policy in place.9 The federal government does not specify the exact nature of the policy but notes that it must cover staff, external experts, commissioners, and others who work for or with the accreditation agency.10 As a further backstop, the Education Department examines accreditors’ conflicts of interest policies when it reviews an agency to decide if it should be able to continue granting access to federal financial aid.11 This measure prevents institutional commissioners, for example, from involving themselves in the review of the college where they work.

Public commissioner requirements

Federal law requires that at least one commissioner and one-seventh of the total number of commissioners represent the public.12 The regulatory requirements for who can serve as a public commissioner are fairly simple. As outlined by Education Department regulations, a public commissioner cannot be:

(1) An employee, member of the governing board, owner, or shareholder of, or consultant to, an institution or program that either is accredited or preaccredited by the agency or has applied for accreditation or preaccreditation;

(2) A member of any trade association or membership organization related to, affiliated with, or associated with the agency; or

(3) A spouse, parent, child, or sibling of an individual identified in paragraph (1) or (2) of this definition.13

The 1992 reauthorization of the Higher Education Act prohibited public commissioners from being part of any trade or membership organization related to the accreditor.14 The Education Department added the above additional restrictions as part of a 1994 rule-making process15 and has not altered the requirement since.

Importantly, the public commissioner requirement does not affect anything else within the structure of the commission. An accreditor can have a commission of any size, as long as public commissioners represent at least one-seventh of the membership. Similarly, accreditors may designate any other type of commissioner they might want. For example, the NECHE has created special commission spots for college trustees in order to bring in that perspective. The public commissioner requirement should likewise not limit any other accreditor efforts at reforming their commissions.

A closer look at public commissioners

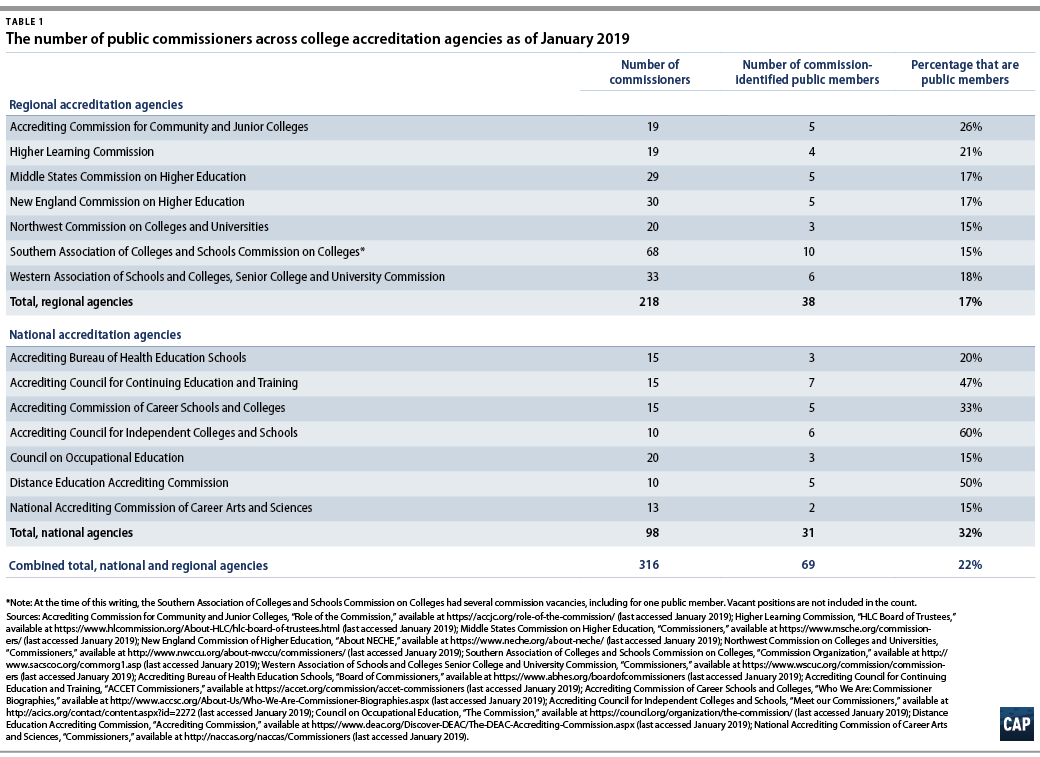

As of January 2019, 68 individuals filled 69 public commissioner spots, based on CAP’s review of accreditor websites. This is out of the 316 total commissioners at the major regional and national accrediting agencies. The 68 public commissioners included one individual who serves on two different commissions. Public commissioners comprised slightly more than 1 in every 5 commission members.

Table 1 breaks down by agency the number of public commissioners identified in this study. It does not consider changes that took place after January 2019. Overall, the table shows that at regional agencies, the share of public commissioners ranged from a high of slightly more than one-quarter at the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges (ACCJC) to the minimum mandated ratio of 1 in every 7 commissioners at the two agencies representing the South and the Northwest.

At national accreditors, about one-third of commissioners are identified as public commissioners, compared with an average of about 1 in 6 at regional accreditors. Two national agencies listed half or more of their commissioners as members of the public. However, many public commissioners lack independence from the higher education field.

Public commissioner backgrounds

The CAP study classified each public commissioner into different categories based on their backgrounds, identified in biographies and resumes on accreditor websites or available on other public sites such as LinkedIn. The author contacted all 14 accreditation agencies to review the classifications and provide any feedback. All but two responded.

Because public commissioners typically have decades of experience, the suggested classification reflects a combination of how long they have been in various roles and their most recent experience. A few examples highlight how this approach has worked. One public commissioner spent four years as an associate vice chancellor at a college. This commissioner also had spent eight years in finance before taking the college administrative role and then returned to a banking job five years ago. Because the total amount of his time in finance is greater than his tenure at the university, and because his most recent job for several years was at a bank, this public commissioner is classified as being in private industry.

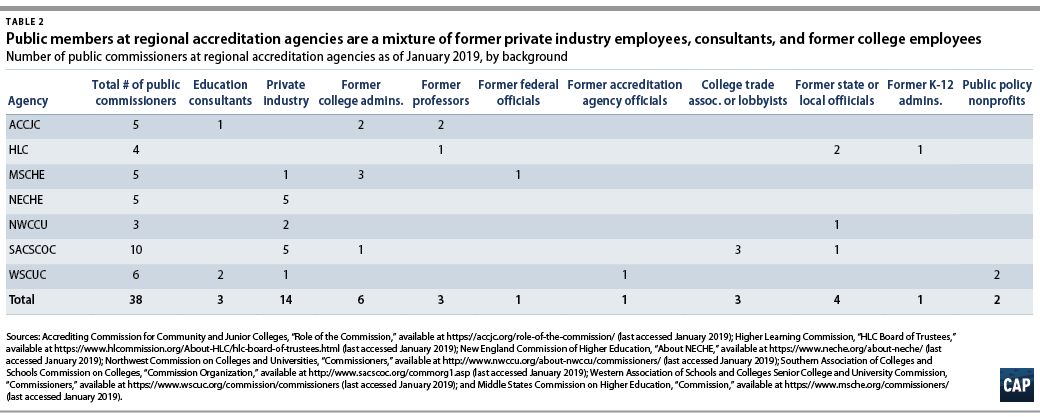

Public commissioners at regional accreditors

Private industry was the most common background for public commissioners at regional accrediting commissions. A little more than one-third of these 38 individuals are lawyers, accountants, consultants in noneducation areas, and business owners, or otherwise make their living in private companies. The next most common background is former college administrators or professors, with nine individuals in this category.

However, there is substantial variation by agency. For example, all five public commissioners at the NECHE are involved in private industry. Meanwhile, two of the four public commissioners of the Higher Learning Commission (HLC) are current or former state or local officials, and one is a former K-12 administrator who recently served in a state role. The HLC public commissioners include a mayor of a roughly 10,000-person city in South Dakota, a former state senator from Kansas, the former head of the New Mexico Department of Veterans Services, and a former professor at the U.S. Air Force Academy.

Two other regional agencies, however, have multiple public commissioners whose backgrounds are more closely tied to colleges than the general public. For example, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) has a unique board structure that allows colleges in each of its 11 states to choose commission members, including a public representative. It thus has a much larger board and more public commissioners than other accreditors. This process has produced three public commissioners with strong connections to institutions of higher education. (As of March 2019, two of the three individuals were no longer serving as commissioners because their terms had ended.) These relationships are permitted under the existing requirements for a public commissioner and thus highlight the weaknesses of the definition.

Two SACSCOC public commissioners are the leaders of trade associations that represent private nonprofit colleges in Texas and Tennessee, respectively. Both of these individuals also have been or currently are registered lobbyists in their states for their organizations.16 This means that their salaries come from dues paid by colleges that are approved by SACSCOC. Though neither of these individuals is currently serving as a commissioner because their terms ended, their selections were allowed under existing rules. That is because neither is a direct employee of a college, and their trade associations are not affiliated with SACSCOC. The third public commissioner who raises concerns about sufficient ability to represent the public interest is a registered lobbyist in Virginia who does uncompensated work for one school accredited by SACSCOC.17 A SACSCOC representative indicated over email that this individual met the definition of a public member because he is neither an employee nor a consultant. Furthermore, the representative noted that SACSCOC commissioners are not allowed to weigh in on reviews of institutions within their states.18

Though these relationships do not amount to a legal violation, it is hard to conceive of how a trade association leader or uncompensated college lobbyist can fully represent the public interest. To be clear, this analysis is not suggesting that these individuals are not qualified to serve as commissioners or have conflicts of interest. There are, after all, conflict of interest policies that all accrediting agencies have in place to prevent cases such as accreditors weighing in on decisions that involve colleges that are members of their associations. Rather, the issue is whether these individuals are qualified to represent the general public interest as a commissioner when their salaries are paid by a group of colleges or they lobby on behalf of a school.

The ACCJC illustrates a different concern wherein it relies on public commissioners who are almost entirely retired academics or administrators. Four of the five public commissioners at this agency are former administrators or professors who previously worked at colleges accredited by that commission. They all retired between 2010 and 2016, so their service does not violate the federal rules governing public commissioners. Again, the individuals in question at the ACCJC appear perfectly qualified to be commissioners. The issue, however, is whether the commissions could have found individuals who bring a more independent and public voice. Individuals who have worked in higher education for their whole career are more likely to bring perspectives similar to the rest of the institutional representatives on the commission. This dynamic undermines the idea that a public commissioner should have some credible claim to bring a more outside voice to the agency’s deliberations.

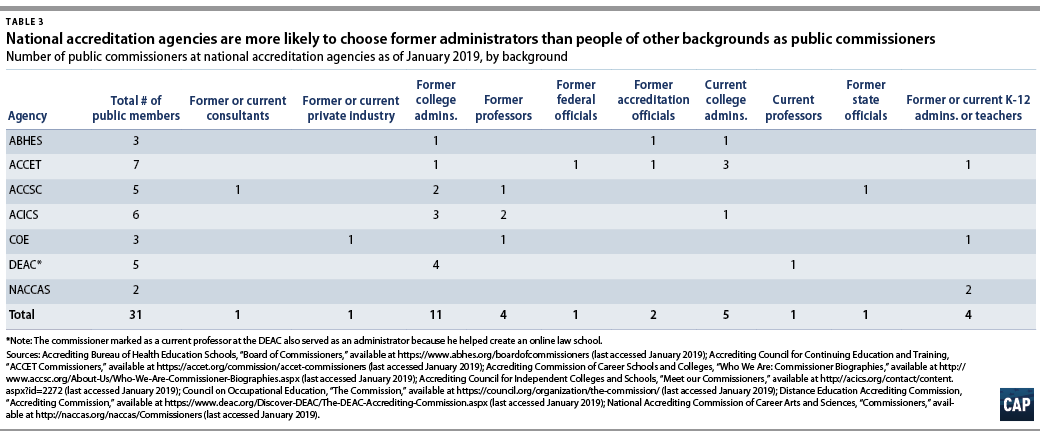

Public commissioners at national accreditors

As of January 2019, more than two-thirds of the 31 public commissioners at national accreditors are current or former college administrators, professors, or college owners. This includes some individuals who served in nonpublic commissioner roles in the same agency in the past and others who have served on multiple commissions. These examples demonstrate loopholes that must be closed. Table 3 provides a breakdown of commissioner backgrounds by agency.

Only one public commissioner at any national accreditor works in private industry, in part because several of the national agencies with a narrow focus maintain separate board seats for private practitioners. For example, the National Accrediting Commission of Career Arts and Sciences (NACCAS) has professional services commissioners.19 These are individuals who work in or run spas or beauty salons and thus can provide the perspective of employers and industry in the specific field on which the accreditor focuses. This designation allows for employer representation beyond the use of public commissioner spots. However, as of January 2019, several of the other career-oriented accreditation agencies, such as the Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges, Accrediting Council for Continuing Education and Training (ACCET), and Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools (ACICS), neither have separate roles for employer or private industry representation nor use their public commissioner spots to bring in that perspective.

The resumes of several public commissioners at national accreditors demonstrate that their backgrounds are not always best suited to represent the general public. For instance, one of the public commissioners at ACCET ran a school approved by that accreditor for many years. She served as an institutional commissioner for that agency as recently as 2016 before becoming a public commissioner in 2017 once she was no longer affiliated with the school.20 Similarly, another ACCET public commissioner was previously an institutional commissioner at that agency but became a public member after taking a job at an institution that had accreditation from a different agency.21 Similarly, the most recent former commission chair at ACICS was a public commissioner who previously served as commission chair in the early 2000s while running an institution approved by that agency.22

There are also several instances of agencies bringing on public commissioners who have previously served on other commissions, such as the Accrediting Bureau of Health Education Schools public commissioner who was an ACICS institutional commissioner until 2017.23 In other cases, the same individual can serve as a public commissioner in different agencies. For instance, one of the ACICS public commissioners was an ACCET public commissioner as recently as 2016.24

To be fair, many national agencies have a larger share of their board comprising public commissioners than the minimum requirement of one-seventh. That means, in some cases, the agencies still might have a sufficient number of public commissioners with more independent backgrounds after not counting those with closer ties to schools the accreditor oversees. However, if the agency is going to require that its board includes greater public representation, then it is important that those commissioners truly do represent the public.25

Public commissioner selection and compensation

There are some key differences between regional and national agencies in terms of how they compensate and select public commissioners. None of the regional accreditation agencies provide any compensation for public commissioners beyond reimbursements for expenses related to attending meetings. In contrast, five of the seven national accreditors do offer honoraria for public commissioners; the only two that do not are the ACCET and Council on Occupational Education (COE).26 Compensation ranges from a few thousand dollars to about $15,000 at NACCAS.27 When asked about this practice in interviews with the author, multiple heads of national accreditation agencies said that they compensate public commissioners as a reflection of the time and work involved in serving on a commission and noted that the sums are not particularly large.28

Regional and national accreditation agencies also select their public commissioners through different processes. All regional agencies select their public commissioners through a vote by the leaders of the institutions that the accreditor oversees. This is the same process used to select all regional institutional commissioners, apart from a few cases where there is an explicitly appointed spot. For example, the ACCJC has a commissioner appointed by the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office.29

National accreditors, however, are far more likely to have their commissioners select and appoint the public commissioners. This is true even in cases where accreditors otherwise elect institutional commissioners. Five of the seven national accreditors appoint their public members, and all of them except for ACICS elect their institutional commissioners. Only COE and NACCAS elect their public and institutional commissioners. Appointing public commissioners gives institutional commissioners even more influence, because they have the final say on which outside voices join them on the board. This may weaken the ability of accreditation agencies to find individuals who are more independent.

Choosing between experience and independence

Many of the challenges observed with public commissioners demonstrate how current federal policy does not do enough to resolve a key tension in filling these roles—whether to prioritize independence and an outside perspective or existing knowledge of accreditation issues. Emphasizing the latter can bring in individuals who can hit the ground running and know how to wade through the mountains of documents produced by the accreditation process. However, individuals who have spent their whole career in higher education may lack the fresh perspective and independence that someone with a different background might bring. Thus, agencies may follow a path that makes the recruitment process easier but ultimately results in less success in finding commissioners who represent the public.

Concerns about public commissioners lacking the experience to be immediately effective highlights the need to pay greater attention to professional development resources. Establishing workshops to bring together public commissioners, educate them about key issues in higher education, and share best practices could help them step into their roles more quickly. These types of resources already exist for individuals who serve on college boards of trustees and should be extended to public commissioners. This could also further help define the mission of public commissioners and stress the importance of incorporating outside perspectives and expertise.

Absent greater professional development, the value placed on experience can explain some of the musical chairs among public commissioners. For example, when ACCET wanted to appoint a public commissioner who knew more about distance education, it chose someone who previously had served three terms at the Distance Education Accrediting Commission, because that individual had experience thinking about accreditation and that specific learning modality.30 On its face, the idea of drawing on existing technical knowledge makes sense. However, if a public commissioner repeatedly moves between accreditors, there is greater risk of perpetuating an insular club with little outside input.

Seeking commissioners that can bring specific technical expertise makes sense, but accreditation commissions should consider whether they should use public spots to bring in individuals who might know a lot about a certain part of higher education. As long as accreditors adhere to the required ratio of public members, they can create any other type of commissioner they wish. As such, if the agencies felt that they needed a spot that could speak to a discrete area within higher education, they could easily establish a new role to fill that need.

Relying on public commissioners for higher education-related expertise also creates a situation where it may be too easy to treat some knowledge as more specialized than it really is. For instance, it is hard to believe that the only possible public commissioner with a background in nursing education that ACICS could find is someone who had just finished a stint in a similar role at ACCET.

Even if they are not using public commissioners to fill specific content needs, accreditation agencies may have standards or requirements in their bylaws that make it harder to find independent individuals. For example, ACICS requires public commissioners to have a demonstrated interest in career education.31 This limitation would make it easier to justify choosing someone who has worked in career education for decades ahead of someone who has broader skills, such as a longtime auditor or lawyer. Though not nearly as limiting, requirements from ACCET that public commissioners should come from fields such as “the administration of higher education, university continuing education, management in business and industry, management of professional or trade associations, public education, government, or such other pertinent fields of endeavor as the Commission determines to be appropriate to the purposes of ACCET” can also unnecessarily limit who might put themselves forward for a public commissioner spot.32

Standards from other accreditors show ways to better ensure that public commissioners have an independent voice. The New England accreditor NECHE, for example, requires that a public member cannot have been active as a professional educator for the past 10 years. The Middle States Commission on Higher Education, meanwhile, prevents anyone currently holding a professional position in education from serving as a public member, as does COE, which prohibits public members from working at any educational institution.

It is understandable that finding an individual who wants to serve as a public commissioner is not easy. However, that does not justify setting up a process that might automatically limit available options and shrink the likelihood of finding independent voices. At the very least, accreditors should eliminate any policies or practices that unnecessarily restrict the pool of public commissioners.

Recommendations to strengthen the federal definition of a public commissioner

The current definition of a public commissioner was set up at a time when Congress was most worried about the ties between accreditation agencies and trade associations. More than 25 years later, it is clear that other loopholes must be addressed. These changes could be made by either Congress or the Education Department, though it would be ideal for change to come from Congress through reforms to the Higher Education Act to ensure that they cannot easily be undone by a future administration.

In particular, the requirements for a public commissioner should mirror and improve upon the best practices already in place at many accreditation agencies. The improved definition should:

- Prevent newly retired administrators or professors from holding public commissioner positions. All public commissioners should not have worked primarily in higher education for at least 10 years. This time limit should also apply to anyone who has owned equity in an institution of higher education.

- Stop individuals who previously represented schools on commissions from serving as public commissioners. Anyone who has served as an institutional representative on a commission should be prevented from serving as a public commissioner on any commission.

- Address broader conflicts of interest. The new definition should expand the ban on what constitutes employment connected to an institution in order to include individuals with any association to higher education institutions or organizations—not just individuals affiliated with the accrediting agency.

Public commissioners also need resources for professional development. This support can help public commissioners get up to speed faster and identify areas where the public has a greater interest, such as making accreditors more transparent and placing a greater emphasis on college outcomes. An independent, private organization without conflicts of interest should provide these professional development resources, which can bring public commissioners across agencies together in settings that do not involve institutional or accreditor representatives. Congress could allocate funds toward competitively selecting the organization that provides this training.

Adopting these commonsense guidelines would send a clear message that public commissioners need to truly represent public interests, while giving them the resources and support do so.

Improving public commissioners is an important first step toward making the decision-making bodies of accreditors more inclusive of other voices that are also invested in the outcomes of higher education. This process should include other constituencies such as students and states. The idea is not to eliminate the idea of peer review, but to recognize that more diverse perspectives will result in a better process.

Conclusion

More than a quarter-century after Congress created the public commissioners requirement, higher education accreditation is once again under the microscope. There are significant public concerns that these agencies are not doing enough to safeguard student and taxpayer dollars from propping up low-quality institutions. As lawmakers work on a reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, now is the time to improve upon the efforts from more than 25 years ago—not toss them out. Making sure public commissioners live up to their name and intended purpose is a good place to start.

About the author

Ben Miller is the vice president for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress.