Introduction and summary

More than 50 years ago, President Lyndon Johnson took the stage at what was then known as Southwest Texas State College to sign the first Higher Education Act. “To thousands of young men and women, this act means the path of knowledge is open to all that have the determination to walk it,” Johnson declared. “It means that a high school senior anywhere in this great land of ours can apply to any college or any university in any of the 50 states and not be turned away because his family is poor.”1

Unfortunately, today, President Johnson’s promise is broken. Nationally, less than half of adults between the ages of 25 and 34 have at least an associate degree, and only 35 percent of black and 28 percent of Latino Americans have achieved this milestone.2 A low-income student is four times less likely to earn a bachelor’s degree than their wealthier peers.3 Similarly, students with disabilities earn bachelor’s degrees at less than half the rate of adults without disabilities.4

As America struggles with college completion, student debt has become an increasing financial danger. About one-fifth of the U.S. population collectively owes more than $1.5 trillion in federal education debt.5 Roughly 1 million people default on their federal student loans every year.6 About half of those students dropped out of college, and almost 90 percent were low-income.7 Taken together, having student debt but no college credential can trap all students—but especially those most in need of economic security—in the cycle of poverty.

A college degree can be a ticket out of this cycle and into middle-class jobs. America’s economy today disproportionately rewards those with a college degree. The data show that college matters: All net new jobs created since the Great Recession went to people with degrees.8 The unemployment rate for adults who have at least an associate degree is just 2.5 percent—nearly half the rate of those who never attended or didn’t finish college.9 Postsecondary graduates are also more likely to have access to employer-based retirement savings or health insurance and even live longer lives.10

This report lays out a sweeping new vision from the Center for American Progress: Beyond Tuition. It is a proposal to restore the promise of an affordable higher education for all and to reduce the burden of student debt. It also includes an emphasis on addressing widespread inequity in opportunity and outcomes. That starts with guaranteeing that a student’s background, particularly their race, ethnicity, gender, or socioeconomic status, will not limit their ability to access, afford, and complete college. Beyond Tuition also ensures there are supports along the way to help students achieve those goals, and that these efforts are backed by strong accountability systems that hold states and institutions responsible if desired outcomes are not met.

Beyond Tuition rests on three core promises:

- The affordability promise: No student should have to borrow for college costs.

- The quality promise: All students are guaranteed a high-quality education that meets their needs.

- The accountability promise: Everyone has a role in student access and success.

Affordability

Beyond Tuition starts with the idea that all students, regardless of their background, should be able to afford a postsecondary education without going into debt. This means not just providing affordable tuition but also helping to cover other associated expenses such as books, housing, transportation, and food. Simply put, the lowest-income students should not have to pay for college, and middle-income students should be able to afford the total price of college based on a reasonable family contribution and with no expectation of having to borrow, save, or work while in school. Moreover, these promises would persist over time, so families do not have to worry about facing large price increases each year. The federal government would make this possible through a substantial new investment matched by state and institutional funding as well as school-based efforts at cost containment.

Quality

Just putting college within financial reach is not enough to close the pressing gaps—by race or ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or other underrepresented identities—in college-going and completion that America faces today. Beyond Tuition, therefore, proposes schools conduct a thorough equity audit of their practices to ensure, among other things, that students from all backgrounds are served by their campus. This means ensuring that admissions practices do not privilege students who are wealthier or come from families that have experience navigating the college application process; that students have access to services such as career assistance, disability support services, writing tutors, and advising; that placement tests are not biased in such a way that they disproportionately result in underrepresented students being placed into remedial or lower-level courses; and that students are taught by diverse faculty, particularly in introductory courses.

Accountability

Beyond Tuition upends the U.S. Department of Education’s current ineffective system of accountability for a more tailored, flexible, and performance-based system that maintains a strong focus on equity. Instead of judging schools on one measure of student outcomes—the loan default rate—schools would sign performance contracts. These contracts would lay out institutional goals for student outcomes on measures of access, completion, and post-school success, and they would provide incentives to keep costs from rising. Institutions would be compared with peer institutions, so schools would not be held to unfair standards and would be given time to improve instead of facing immediate loss of funds.

Looking ahead

Now is the time for a bold rethinking of America’s higher education system. Beyond Tuition embodies the idea that education beyond high school is a civil right. It will turn the tide of repeated state budget cuts that threatens to privatize the United States’ system of public higher education and launch millions of graduates into the middle class.

Beyond Tuition: An overview

Equity is an imperative

Beyond Tuition is not just a universal commitment to making college affordable; it contains multiple proposals aimed at improving equity within America’s postsecondary education system. The overall goal is to ensure that there are no longer gaps in student access to and completion of higher education based on identities such as students’ race, gender, income, disability status, parental status, or veteran status.

This goal starts with a large investment in affordability. Though the Beyond Tuition promise helps families across the income spectrum, reducing financial barriers should help to close gaps in access and completion for low-income students—a group that disproportionately includes students of color, single parents, and others who do not receive the support they need to enroll in and complete college at the same rates as their wealthier peers. Though this policy alone would not solve wage and employment discrimination that occurs when these graduates enter the labor market, it would reduce students’ current need to devote portions of their paychecks to student loans and risk of facing long-term financial consequences of default, as well as make it much less likely that students will have to drop out of school due to financial barriers.

Tackling equity in higher education, however, must go beyond reducing student debt. Colleges need to ensure that resources and supports flow to the individuals who need them most. This means designing a college experience that responds to students’ individual needs, such as by helping low-income students transition to higher education; employing a diverse and welcoming faculty, which can help all students, but particularly students of color; and providing accessible educational experiences for students with disabilities. That is why Beyond Tuition contains an additional emphasis on making colleges assess whether their supports are working and students are getting the help they need, as well as on ensuring that policies that may be well-intentioned are not creating disparate effects.

Accountability systems, too, must emphasize equity. Not a single measure of student outcomes mandated in the Higher Education Act requires assessing results by student subpopulations, such as by race or ethnicity, gender, disability status, or socioeconomic status. Accreditation—the system by which colleges obtain eligibility for federal financial aid dollars—has been ineffective at weeding out schools that offer their students a very poor bargain and rarely considers outcomes by race or gender in its reviews of colleges.11 The result: Pervasive gaps in student outcomes can be masked by overall institutional performance. America’s current postsecondary education system has work to do to achieve these equity goals.

The number and percentage of students of color, students with disabilities, and low-income students attending college has risen over time, but an erosion of public support for education has severely undercut opportunities to serve these students well.12 Inequality in primary and secondary schools—such as gaps in funding, access to high-quality teachers, and programs for students with disabilities—means that many students leave high school underprepared for college. If they do enroll in higher education, they must contend with resource-starved institutions—the direct result of significant state disinvestment in public higher education. Lack of preparation paired with poorly resourced institutions leads to decreased odds of graduating.13

Structural elements of financial aid programs can create affordability challenges as well. For instance, LGBTQ students whose families have turned them away may struggle to be acknowledged as independents adults for federal financial aid purposes, leaving them without sufficient support or potentially locked out of the system entirely.14 Students with disabilities, including those with mental health conditions, may run out of federal financial aid eligibility if they need to take more time to finish a program while managing a disability.15

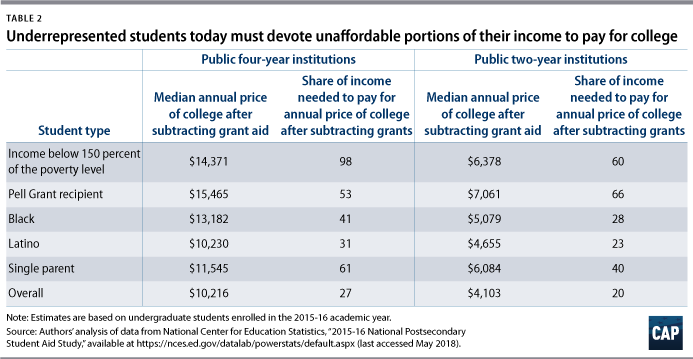

Meanwhile, the buying power of federal financial aid has shrunk dramatically over the past several decades. The original vision of the Pell Grant—the nation’s signature investment in higher education support for low-income students—was that it would cover three-quarters of the total price of college.16 Today, the Pell Grant covers less than one-third of an in-state public four-year education.17 To compensate for the increased costs and lack of aid, students have taken on significantly higher levels of debt.

The reliance on student debt in pursuit of a college degree has particularly pernicious effects on low-income students and students of color. The federal government adopted student loans decades ago as a tool to help middle-income families finance the cost of college, while low-income students received grant aid instead. Today, most student loan borrowers are low-income, and a disproportionate share of students of color take on debt. For example, nearly 80 percent of African American students borrow for college, compared with 60 percent of all students. Similarly, women are more likely to borrow student loans—and take on greater amounts of debt when they do—than are men.18

Dependence on student debt makes the very act of attending college riskier for low-income and underrepresented students. When borrowers default, they can have their credit ruined, wages garnished, or tax refunds seized, all because their attempt to learn and to follow a path to the American dream did not pay off.19

Almost 30 percent of borrowers default on their federal loans within 12 years of leaving school—an outcome that is highly correlated with race and class.20 High default rates for underrepresented groups are particularly concerning. Twelve years after entering college, the typical African American borrower owes more on their student loans than they originally borrowed, while the typical white student pays down 35 percent of their balances.21 In that same time frame, nearly half of African American borrowers default on their loans, including 1 in 5 who finish a bachelor’s degree. By contrast, just 6 percent of white bachelor’s degree graduates default during that same time period. Similarly, students who identified as having a disability when they began college have higher default rates than their peers without disabilities.22

While the data alone cannot illustrate exactly why borrowers of color have more student debt and worse outcomes than their white peers, there are higher education-specific and broader economic reasons that might explain the results. From the postsecondary education side, students of color complete college at lower rates than their white peers, and data show that borrowers who do not finish college are more likely to default than those who graduated.23 But looking only at completion rates ignores the potentially significant role of larger economic circumstances. For instance, there are large gaps in pay and employment opportunities by race and gender that can affect how much money a borrower can devote to loan payments.24

Even borrowers with the same incomes may have very different levels of familial wealth. As detailed in other CAP reports, black and Latino households have median wealth that is roughly one-tenth that of white families.25 This gap persists even among college-educated households. Families that have wealth in the form of savings or a home may be able to tap those sources to pay for college, while those that lack these options may have to resort to student loans. Similarly, a struggling borrower who can turn to their family for assistance may be less likely to default than a lower-income student who does not have such a safety net.

These issues are borne out in the data. Nearly 90 percent of students who entered college in 2003-04 and defaulted on a loan by 2015 also received a Pell Grant; 70 percent were first-generation college students; and half never earned a certificate or degree within six years of entering college.26 For these students, what should have been a tool for finishing college is instead a financial burden that will haunt them for years.

These poor repayment outcomes do not just affect borrowers; they also affect borrowers’ children. Twenty-seven percent of undergraduate borrowers who had a child when they entered college in 2003-04 defaulted on a student loan by 2015.27 The majority of those parents were single. The negative consequences of default can not only lock these students in a cycle of poverty; they can stymie opportunities for students’ children as well.

The United States never set out to build a debt-based system of higher education—especially not one that puts low-income students and those already in poverty at the greatest risk of financial ruin. To ameliorate these wrongs and truly promote equity in opportunity and outcomes, the federal government must significantly reform the system, first by focusing on making college affordable for all families.

The affordability promise: No student should have to borrow for college costs

Surveys show that cost is the biggest reason why students do not enroll in or fail to complete college, far outstripping academic ability or performance. The high cost of college is much more profound than commonly understood because tuition is only part of the equation. At many schools, particularly community colleges, the cost of nonacademic expenses—such as food, rent, and transportation—are far greater than the price of tuition and school fees. The result is that too often the dividing line between success and failure in American higher education is hunger, housing, and child care—not humanities, history, and calculus.

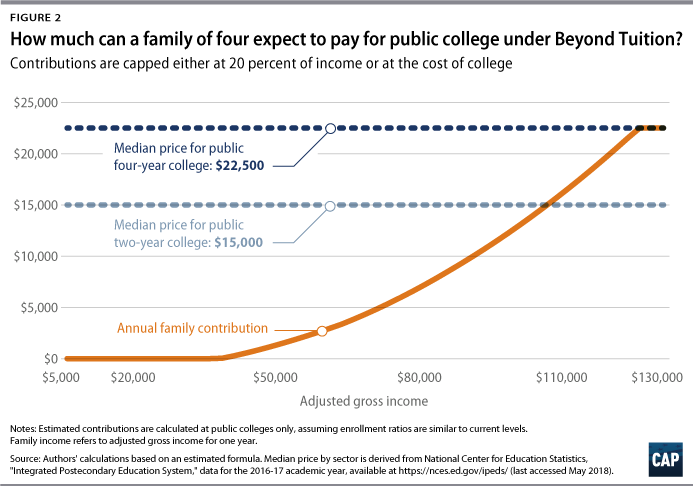

Beyond Tuition acknowledges the importance of tackling the entire cost of higher education by striving for free public education for students whose families make less than 150 percent of the federal poverty level—just less than $38,000 for a family of four.28 Middle-class families should pay no more than 10 percent of their income to send a student to college, and no family should be expected to pay more than 20 percent of their income. Students choosing a private nonprofit college or a public institution out of their home state would be expected to contribute more, but they should have a similar promise tied to their income, ensuring students retain significant choice when it comes to affordable college options. Families would not be expected to contribute from their savings; no student should be forced to work in order to receive aid; and adults as well as traditionally college-aged students could take part.

There is crucial distinction between Beyond Tuition and other affordability proposals that have advocated so-called free college or debt-free college but have generally only addressed tuition costs. Beyond Tuition aims to cover not just core academic expenses such as tuition, fees, books, and supplies, but also the other costs associated with attending college such as food, housing, and transportation.

Under this proposal, states, institutions, and the federal government would share in the cost of this investment through a matching program. The federal government would cover 70 percent of costs on average, with the match required of each state or institution varying based upon levels of wealth, the size of the eligible population, and the number of low-income and underrepresented students served. As a result, poorer states and private nonprofit institutions with fewer resources would face more affordable matching requirements.

The quality promise: All students are guaranteed a high-quality education that meets their needs

A low- or no-cost education is not valuable if it doesn’t give students the support that they need to reach graduation and ensure graduates have the knowledge and skills they need for lifelong success.

Too often, institutions and public policies are designed to serve the so-called traditional student—one who enters college at the age of 18, studies full time, and has no other major responsibilities outside of school. The increasingly common reality is that the average student is older, attends college part time, works long hours, is raising a family, or does all of the above.29 Others are balancing their studies while also managing a disability or facing challenges that can come from being a veteran, undocumented, or formerly incarcerated. Or they may be grappling with discrimination based on race, gender identity, sexual orientation, or other characteristics. Educational options therefore need to not only impart the necessary knowledge and skills for success, but also provide the supports needed to help students make it to graduation.

The quality promise addresses how colleges serve their students. It does this by asking colleges to conduct an equity audit: a top-to-bottom review of policies, practices, and resources in order to identify areas that might be contributing to gaps in outcomes for key groups of students based on characteristics such as race or ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, and whether they are a veteran or have a disability. At selective colleges, this would include ensuring that recruitment not only takes place at wealthier high schools that often lack racial or socioeconomic diversity and that early admissions policies do not fill up entering classes with students of means. Equity audits would also touch on issues that affect all colleges—not just the wealthiest or most selective ones. This includes ensuring that advising, tutoring, career services, and other supports are available and used by students from all backgrounds. These audits should also consider the diversity of faculty—especially those teaching introductory courses—as well as the types of graduates who are hired by employers that recruit on campus. Finally, the equity audit should review physical and programmatic accessibility to ensure that students with disabilities are fully included in all facets of academic and social life on campus.

The accountability promise: Everyone has a role in student access and success

Making America’s postsecondary education system work requires ensuring every participant is bought in and held accountable for doing their job. The federal government, states, and colleges must renew their investments and live up to their roles in the system. In the postsecondary system, the federal government spends about as much as do states, yet accountability for these dollars comes down to sanctioning only a handful of the thousands of colleges in this country each year, even as more than 1 million borrowers default on a student loan annually.30

Beyond Tuition safeguards this significant federal investment by establishing a new system of accountability through performance contracts. These documents would bind each party to do their part. For federal and state governments, this would mean providing necessary funding levels and oversight. The performance contracts for institutions would establish a set of benchmarks for student access, completion, and post-school success that would be tailored to schools based upon their type, resources, demographics, and historical mission—all of which would be presented for key populations. Schools that far exceed expectations would receive bonuses. Those that fall short would be given time to improve but would then face a set of consequences that start with public disclosures, move to reduced government funding with continued poor performance, and eventually culminate in the loss of access to federal financial aid if unacceptable results persist.

Overall, these performance contracts would move federal accountability away from the narrow system that exists today, which only penalizes a few institutions with the very worst results, to a broader and more flexible regime that emphasizes completion and equity while pushing all colleges to improve.

The end goal

The postsecondary system envisioned by Beyond Tuition will ensure that achieving the American dream through postsecondary education will no longer be out of reach for students based on who they are or what family they come from. The total price of college will not burden families, hard-earned taxpayer dollars will support quality learning options, and a new system of shared responsibility will ensure strong accountability so that dollars are well spent.

Removing barriers—both those that are economic and those that are structural—will allow America’s postsecondary education system to produce the results that America needs to succeed in the decades to come. The investments in Beyond Tuition will put the United States on a path to having more than 60 percent of its adults holding a postsecondary credential—a mark needed to return America to the ranks of world leaders in college completion.31 Importantly, the goal of Beyond Tuition is to make these investments not to simply raise the attainment levels of the most privileged groups, but to dramatically increase attainment for low-income students, students of color, students with disabilities, and those with other identities and backgrounds who have not traditionally completed college at high rates, while shrinking the risk and harm of the current debt-based system.

The affordability promise: No student should have to borrow for college costs

The cornerstone of Beyond Tuition is a robust new federal investment that, with matching state, local, and institutional dollars, will strive to ensure that no student has to take on debt to afford the total cost of college. This promise covers not just tuition, fees, books, and supplies, but also housing, transportation, and food.

The affordability promise in Beyond Tuition is unique compared with other policy proposals that aim for affordable higher education. (see text box below) Adults as well as traditionally college-aged students could take part, and no student would be required to work, although a student could exercise that option if they wanted or needed to.

Beyond Tuition would not offer outright free college to all. Instead, it would scale aid based on income, providing full tuition, fees, and daily living benefits to low-income students while expecting families with higher incomes to make a predictable and affordable contribution if they have the means to do so. The plan would be set up so that families could afford this contribution from their current income without the expectation that they would have saved for years prior.

Removing both work and savings requirements makes the plan more straightforward than others and promotes equitable access. Expecting a student to work may sound reasonable, but such a rule creates more problems than it solves. Verifying work hours would require expensive administrative resources, and working too much—beyond 15 hours, according to research—may hinder student achievement.32 Further, leaving savings out of the plan means that families with moderate incomes would not be forced to save when it may not be feasible to do so and allows adults to enroll immediately instead of waiting to build savings. It would also not punish people with disabilities who may have to live under extremely low asset limits that prevent them from saving money.

Comparing Beyond Tuition with other affordability proposals

Many of the concepts in Beyond Tuition are compatible with other bold proposals for college affordability. It contains a clear promise for families—they can pay for college out of pocket—and includes a robust federal-state matching program to make this guarantee workable. That structure is similar to ideas for free tuition that some legislators have proposed, including the College for All proposal from Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT); the America’s College Promise that the Obama administration developed; and the Debt-Free College Act of 2018 from Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI).33 A detailed comparison of Beyond Tuition and these plans is available as an appendix.

Similarly, the notion of making a clear guarantee to students and families is similar to the promise programs that exist in cities such as Kalamazoo, Michigan, and states such as Tennessee and New York, as well as other places across the country, which all provide free tuition at community colleges, and even some four-year schools.34

At the same time, Beyond Tuition does more than most of these programs. First, it extends its affordability promise not just to tuition but to the entire cost of college and provides access to all public and participating private nonprofit colleges. Only the Schatz plan offers to cover the full cost of college, but that plan is limited to public institutions. Beyond Tuition also allows private nonprofit colleges to participate as long as they abide by the affordability, quality, and accountability promises. This ensures that students have access to a variety of institutions, allowing them to find the best fit. The plan is also unique in that it is available to all students regardless of their age or GPA, whereas many state-based promise programs only provide access to recent high school graduates.

Beyond Tuition also goes beyond a universal affordability guarantee to require targeted quality and accountability efforts to ensure that this program achieves its goal of closing equity gaps. Adding these components on top of federal investments ensures that students would not just receive an affordable education, but one that is valuable and accommodating for students of all backgrounds.

Family or student contribution

Beyond Tuition asks students or their families to make a contribution based on where their income falls compared with the national poverty level. The contribution would be binding, meaning that participating colleges could not charge more—a major departure from current practice, in which colleges routinely charge families thousands of dollars more than their official expected family contribution.35 This idea builds on concepts that the Lumina Foundation established in 2015, which suggested an affordability benchmark for students based in part on not expecting families to pay too large a share of their income for college.36

Families that make less than 150 percent of the federal poverty level—or $37,650 for a family of four—would not be expected to make any contributions for a public in-state college.37 Families above that level would make contributions that increase with their income such that middle-class families would pay no more than about 10 percent of their discretionary income, defined as earnings over 150 percent of the federal poverty level. Higher-income families would never be expected to pay more than 20 percent of their income for an in-state public college. Because household budgets are finite, the total family contribution would not increase when a family has more than one student in college; rather the contribution would be split among the children.

Students attending participating private nonprofit colleges would receive slightly different terms. At those institutions, middle-class students would contribute up to 20 percent of their discretionary incomes, while upper-income students would pay no more than 30 percent of their income. While it is important to ensure that private nonprofit colleges remain within reach for students of all backgrounds, it is also reasonable to expect families to take on more of the cost if they choose to attend a private nonprofit college.

The rules are also slightly different for adult students who do not have children or other dependents. For those earning more than 150 percent of the federal poverty level—$18,210 for a single person—the income expectations start at a higher share and increase at a greater rate, though the overall caps are the same.38 This is because these students generally have the same living expenses whether or not they are in college. By contrast, parents of younger, dependent students often must pay for additional living expenses for their students to live on or near campus, which is a burden that adult students do not shoulder. And student parents may face additional costs for child care in order to dedicate enough time to classes and studying. Therefore, income expectations for student parents are the same as those for dependent students.

The Beyond Tuition aid proposal is thus simpler and more predictable than the current financial aid system. Today, families have to complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) each year, with some answering questions about special circumstances and assets that are not easily obtainable from federal tax returns.39 In contrast, Beyond Tuition would calculate family contribution amounts solely based on tax records.

Relying on tax records means this system does not factor in wealth when determining family contribution levels. It is true that two families with identical incomes may have very different amounts of wealth. However, assessing wealth, or lack thereof, to set family contribution levels would add complexity to the system. Providing this additional information would place a disproportionate burden on lower-income families that outweighs the value it would offer in identifying families whose aid packages should be lowered.

Tying family contributions solely to current income also sends an important message: College should be affordable through out-of-pocket spending. Moving away from expectations that families save extensively for college has important equity implications. The median wealth of black households is one-tenth that of white households.40 Even comparing families with similar incomes, families of color generally have much lower wealth compared with white families. A savings expectation thus automatically puts households of color in an unfair situation.

Lack of a savings requirement is also friendlier to the roughly half of students who are on their own for financial support.41 These individuals usually do not have the option to save prior to enrollment and should not be disadvantaged or forced to delay their enrollment in order to save money for school.

Grants

Under Beyond Tuition, the gap between the full price of college and a family’s binding contribution is filled with grants. Students would receive enough funding from the federal government, states (if attending an in-state public college), and their institution to ensure that the only out-of-pocket cost they face would be for their determined contribution.

The following example illustrates how this would work for a student attending an in-state public two-year college that has a total price of $15,000. The student’s expected contribution would be $3,000, which means they would receive $12,000 in grants. A different student with an expected family contribution of $10,000 would receive $5,000, and so on.

Loans

Beyond Tuition anticipates that families should be able to pay for college out of pocket. But it also recognizes that sometimes a contribution that seems reasonable on paper may not be realistic in light of other financial obligations. If a family cannot contribute its share, the student could borrow part or all of the expected contribution with an affordable federal loan to cover the costs. Students would have the option to automatically pay these loans back based upon a reasonable share of a borrower’s income. There would be no expectation for low-income students to borrow, given that their family contribution is zero if their household income is less than 150 percent of the federal poverty level.

Student eligibility requirements

Postsecondary education takes many forms beyond a bachelor’s degree, and Beyond Tuition recognizes the broad range of undergraduate credentials available. To that end, students could use their benefits for any programs eligible for federal financial aid at an accredited public or private nonprofit institution, so long as that school abides by the affordability promise and the quality and accountability terms that come with it. Benefits would be available to all residents of the state, as well as to Dreamers and individuals in similar circumstances.

Students would also have sufficient time to use their benefits. Individuals who do not already hold a bachelor’s degree could participate in Beyond Tuition for the equivalent of six full-time years of undergraduate study. Adults who already have a bachelor’s degree could also participate for the equivalent of up to two additional years if they have been out of school for at least a decade or are an in economically distressed area in order to give them the opportunity to train for a new occupation. Students could not use the program to pursue graduate education.

Participating students would not have to meet any set federal academic requirements. This is because mandating a GPA requirement or other bar for achievement risks creating extreme cliff effects where a small dip in performance could cost a student thousands of dollars. Additionally, students who have experienced inequities in their youth may not have received appropriate preparation for college-level coursework and thus may struggle academically—especially as they adapt to life in college. These students deserve an equal opportunity to gain an education, so it is important that Beyond Tuition not operate similarly to a merit scholarship that rewards those with the strongest academic records.

Instead of strict federal academic requirements, Beyond Tuition participants would have to abide by school-set satisfactory academic progress policies, which typically include requirements such as earning a certain number of credits after the first year of study.42 Schools would also be expected to evaluate the effects of their academic progress policies to ensure they do not raise equity issues.

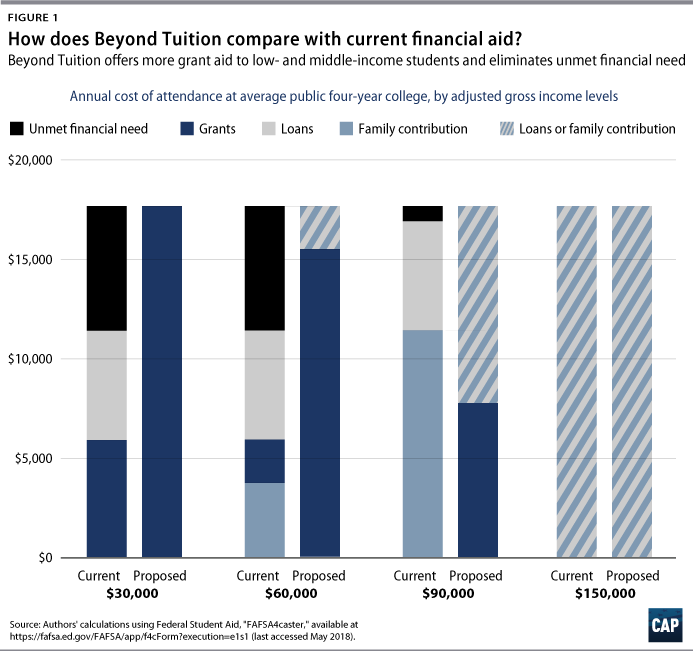

Effects

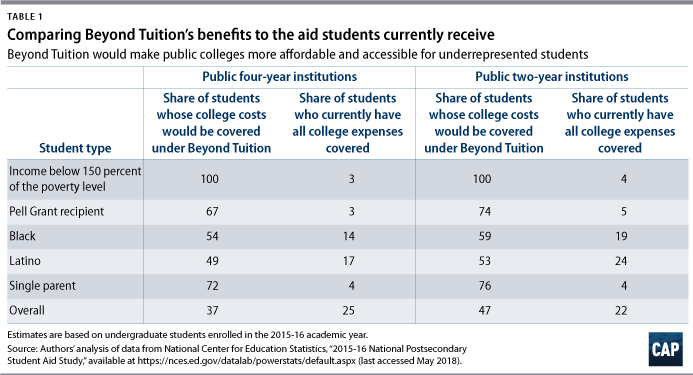

Beyond Tuition will change the game for low-income families. Currently, students with the lowest incomes who cannot contribute any money to college receive about $12,000 in support from the federal government—nearly half of which are loans.43 For a student at a four-year college, this leaves a funding gap of about $8,000. Under Beyond Tuition, those students would be fully funded through a combination of federal and state funds and would not borrow at all. Middle- and higher-income students would receive grant support if they need it and have a better understanding of how much they would have to pay. They would also be eligible to take on loans if they could not afford part or all of their family contribution.

These are dramatic improvements in the level of support for students compared with what the U.S. postsecondary system provides today. In 2015-16, just 3 percent of students at public four-year colleges whose families made less than 150 percent of the federal poverty level had their entire cost of college covered.44 Beyond Tuition would aim to fully cover costs for all of these individuals. Similarly, Beyond Tuition would provide full benefits to two-thirds of Pell Grant recipients and nearly three-quarters of single parents at public four-year colleges—groups that face bills upwards of $10,000 after subtracting grants each year.

Beyond Tuition also has significant implications for racial equity in college access and affordability. Under the program, about 54 percent of black students at four-year public colleges and 49 percent of Latino students would not have to contribute anything for college. That is an increase from 14 percent and 17 percent, respectively, under the current system. Similarly, 59 percent of black students and 53 percent of Latino students at community colleges would not pay anything for college.

Paying for Beyond Tuition

The costs of Beyond Tuition would be shared between the federal government, states, localities, and institutions. For public colleges, the federal government would provide funds to states that, on average, cover 70 percent of costs not covered by family contributions. States, localities, and institutions would fill in the rest. The exact matching rate would be determined by a formula that takes into account a state’s wealth, size, and noncollege-educated population, among other factors. As a result, lower-income states would receive a higher federal match than wealthier ones.45

The matching rate for states would also automatically adjust during a recession so that states contribute less and the federal government spends more when budgets are tight, as states cannot run deficits. The match would change as the economy recovers and would be regularly adjusted based on changes in a state’s long-term economic outlook.

Once federal funds flow to a state, it would have the option to ask public four-year institutions to cover a share of the state match. However, states would have to take into account a school’s economic circumstances when considering any institutional contribution. The idea is that a well-resourced, highly selective college may end up sharing the cost, but a community college would not. Similarly, states could only expect local contributions in areas where they are currently provided, such as for some community colleges.46

There is a risk that states may choose to decline matching funds the way some have done after the Affordable Care Act offered to pay for most of the cost of expanding Medicaid.47 While this plan cannot overcome a completely political decision to leave money on the table, it does provide a strong incentive for states to participate. Beyond Tuition provides extremely valuable benefits to students across the income spectrum, and the rewards for institutions also create reasons for them to advocate in favor of this investment. Should a state not participate, it could risk loss of residents and therefore tax revenue, ultimately hurting its overall economy. This pressure would create a broad constituency to support this program and demand state acceptance. Students in nonparticipating states maintain access to the existing federal financial aid system.

Private nonprofit colleges

Private nonprofit colleges could choose whether they want to participate in Beyond Tuition. Signing on would allow them to receive substantial federal aid for their students. In return, they would be required to commit to the terms of the three core promises. Students at nonparticipating private colleges maintain access to the existing federal financial aid system.

Participating private nonprofit colleges would have their own set of matching requirements. The amount of the match would vary based upon the institution’s wealth, its enrollment of low-income students and students of color, and whether it has a historical mission to serve these populations. With this structure, under-resourced private nonprofit colleges and those that do their part in educating vulnerable populations—such as historically black colleges and universities or other minority-serving institutions—would be able to participate at a more affordable matching rate compared with wealthier institutions.

Size of federal payments

Beyond Tuition calculates payments separately for academic and nonacademic expenses. Spending on direct academic costs such as tuition and fees would be based on the national per-student average, then adjusted for each state based upon the formula-determined match rate. Over time, these figures would rise with inflation using an index of consumer prices. Cost increases above inflation would be borne by institutions and states.

The benefits covering living expenses would be handled separately. For these funds, the federal government would generate a living cost estimate for the area where the school is located. The federal government would perform this role in order to contain costs, as institutions sometimes arbitrarily set cost of living estimates, and to ensure these estimates cannot be gamed to garner additional federal aid. Students would be eligible for up to $10,000 in living expenses. This amount would be increased annually with inflation and reviewed periodically to ensure it is in line with cost of living around the campus.

Cost containment

Beyond Tuition is designed to incentivize cost containment. Because the federal and student payments are fixed and rise based on inflation, any additional price increases must be footed by either states, for public colleges, or institutions, for private nonprofit colleges.

For example, imagine that a student with no ability to pay for college has a cost of attendance of $10,000—$7,000 of which the federal government pays and $3,000 of which the state pays. The following year, the federal contribution rises with inflation to $7,100, but the price of tuition increases faster than inflation to $10,300. The state and school must find a way to cover that additional $200.

While institutions would have strong incentives to contain costs, the matching structure of Beyond Tuition also ensures that states could not continue to disinvest in higher education. Currently, there is nothing that stops states from cutting funding for colleges if they wish, and they have done so deeply in the years since the Great Recession.48 Under Beyond Tuition, however, state cuts would risk not fulfilling the matching requirements or the affordability promise, jeopardizing federal aid eligibility for thousands of students.

The federal government’s role in determining cost of living stipends would provide an additional bulwark against cost inflation. It would ensure that cost of living funds would not vary too much within the same geographic area, resulting in some students receiving more than they need and others not enough.

The result would be a mutually reinforcing funding system that would offer the best opportunity in decades for bending the cost curve in higher education. The federal government would ensure its money buys affordability; schools would receive the resources they need but be encouraged to keep prices low; and states would have clear but reasonable expectations for maintaining sufficient funding. And, most importantly, students would benefit from price certainty and affordability.

Cost of the system

Rough projections show that Beyond Tuition would cost the federal government $60 billion per year—$42 billion for public colleges and $18 billion for private nonprofit colleges.49 If applied to only public colleges, then the program could provide a higher living benefit of up to $12,750 a year for roughly the same cost. These figures are net of existing spending on Pell Grants, higher education tax benefits, and other items that currently support college affordability. The cost of the program would be lower in the first few years as states gradually opt into the plan.

This is a large but ultimately worthwhile investment in helping students access the middle class and bolstering the U.S. economy. It would cost far less than the tax law enacted in 2017, which is badly skewed to benefit corporations and the rich and will cost an estimated $281 billion in 2019 alone, according to the Congressional Budget Office.50 Unlike those cuts, the greatest benefits from Beyond Tuition would go directly to the individuals who are currently the least likely to access and complete college as well as to the families struggling to afford the high cost of postsecondary education. This should spur national attainment rates, producing a more educated workforce that could in turn boost productivity and growth.

The quality promise: All students are guaranteed a high-quality education that meets their needs

Access to affordable college is not enough if students cannot finish or if the education they receive does not give them the knowledge and skills they need for lifelong success. That is why Beyond Tuition goes further than affordability to also ensure students have the support that they need to cross the finish line with a meaningful credential.

Beyond Tuition would make good on its quality promise in three ways. First, participating colleges would conduct an equity audit—a thorough review of policies, practices, and resources to identify areas that might produce gaps in outcomes for key groups of students, particularly but not limited to groups identifiable in existing data such as by race or ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, or whether the student is a veteran or has a disability. Private nonprofit colleges would also have to abide by the same standards of nondiscrimination as public colleges. The goal is to ensure colleges are looking at their operations through an equity-focused lens.

Second, colleges would be expected to use any new funds received from the affordability investment to bolster academic quality or provide increased supports such as child care, advising, disability support services and accommodations, mental health counseling, among others. Finally, institutions would work with accreditors on program assessments, which regularly assure that credentials are providing a reasonable social, intellectual, and economic return on students’ investment.

Identifying gaps through equity audits

Colleges are often designed for more traditional learners—students who come straight from high school, attend full time, and live on campus. The result is these institutions may have policies that are not well-designed for today’s students—those who are older, attending part time, or balancing work and family commitments alongside school.

Ill-designed policies may unintentionally disadvantage today’s students, who may not get a fair shake at access, receive all the academic help they need, or find a job once they graduate. Some selective colleges, for example, fill as much as half their classes through early admission programs—options that disadvantage low-income students who cannot make a binding choice before they are offered a financial aid package.51 Or it may be that placement tests used for remedial courses have flaws similar to other standardized tests, where the content of the test disadvantages students of color.52

To uncover these issues, all schools participating in Beyond Tuition would be expected to complete regular equity audits—internal reviews of key policies and practices to identify those that fail to serve underrepresented students effectively. The concern is not that schools are widely engaging in intentional discriminatory behaviors, rather that well-intended practices can have inequitable results. Audits would be conducted every few years, giving institutions time between each one to address identified shortcomings.

The equity audit would examine everything from college recruitment to career services, including:

- Admissions policies at selective colleges, such as the demographics of high schools where the college recruits, the makeup of students admitted through early admissions, and legacy admissions beneficiaries.

- Access to and participation in pre-college and first-year experience offerings, such as orientation and bridge programs.

- Educational supports, including remedial placement, academic resource center usage, and how students are differentially affected by satisfactory academic progress policies, which set a bar for the minimum performance acceptable for continuing to receive aid.

- Student support services, including the demographics of students served by academic and career advising, child care centers, and mentoring programs.

- Instructor diversity, including faculty overall as well as teachers of core and introductory-level courses.

- Physical accessibility on the grounds of the college and programmatic accessibility of campus services, activities, and programs.

- Demographics of students hired by employers who recruit on campus or with which the college collaborates on work-based programs.

Audits would be made public, and institutions would be expected to make progress in closing identified gaps. Failure to progress on challenges over time would have increasingly strong consequences, which are described in the accountability section of this report.

Providing meaningful supports

Building a welcoming and supportive college with high-quality programs costs money. That is why any extra funds that flow to schools through Beyond Tuition must be used to enhance academic quality.

Colleges may improve academic supports for students through a variety of means. Those with a significant number of students who enter school academically underprepared could choose to implement proactive advising models, create tutoring centers, or rethink how they place students into and deliver remedial education. Others could choose to improve teaching and instruction by prioritizing classroom performance for faculty or hiring more diverse instructors in a wide range of fields.

Institutions could also use these funds to provide nonacademic supports to students. These could include low- or no-cost child care centers, health and counseling services, mentorship programs, and accommodations and physical access services for students with disabilities. They may also bolster underrepresented students—such as undocumented students, LGBTQ students, students with disabilities, veterans, formerly incarcerated individuals, and students of color—by creating resources and campus communities targeted to their needs and ensuring that those resources are accessible. Colleges would also be required to take an active role in addressing situations that threaten the safety and well-being of their students, including sexual assault and various forms of discrimination, by providing additional training to faculty, staff, and campus safety officials or by taking meaningful action against those who violate the rights and well-being of members of the campus community.

Program assessments ensure quality credentials

Guaranteeing quality also means considering teaching and learning. Every program a college offers should provide a baseline guarantee that students will have the skills that they need to be successful when they finish their credential.

To achieve this goal, colleges must be intentional about creating and administering programs of study that are worth the time and money that students—and taxpayers—invest. Each program should articulate clear learning outcomes and expectations for the length of the program. At two-year colleges, degree programs should be designed with clear transfer options with nearby institutions. Programs that have connections to specific industries should provide workplace training opportunities and be developed in coordination with local industry. Shorter-term credentials should be easily stackable, meaning they help fulfill the requirements of higher degree programs, to ensure that students can continue their educations without paying for credits that will not transfer to the higher credential.

While academic quality is imperative, the federal government is not well-equipped to assess this issue. Therefore, Beyond Tuition creates clear expectations that accreditors would be responsible for these deeper dives into the quality of an institution’s programs. Accreditors should also probe institutions that have gaps on equity audits or come up short on required performance measures to find out why these problems occur. These expectations baked into Beyond Tuition create a clearer mission for accreditors than they have today. Currently, accrediting agencies have a wide mandate to look at all aspects of an institution without a clear statement of what they should prioritize.53 Beyond Tuition addresses this shortcoming.

The accountability promise: Everyone has a role in student access and success

Beyond Tuition would safeguard the federal government’s significant postsecondary investment by establishing a new system of accountability through performance contracts. These documents would create a binding pact among institutions, states, accreditors, and the federal government. Federal and state governments would commit to providing necessary funding levels and required oversight. Institutions’ performance contracts would establish a new set of benchmarks for student access, completion, and post-school success that are tailored to their type, resources, demographics, and historical mission and are broken down for key populations. Schools that far exceed expectations would receive bonuses in the form of extra money or a reduced institutional matching requirement, while those that fall short would be given sufficient time to improve before facing increasingly strong sanctions.

More specifically, parties would agree to the following:

- Institutions: Meet required performance targets; conduct and publish the equity audit and address any issues identified; provide any required matching funds; and use additional funding to improve educational quality and student supports.

- Federal government: Provide sufficient funding; enforce institutional performance requirements; define outcome indicators; and determine cost of living estimates.

- States: Provide any required funding matches and make any necessary adjustments to performance funding systems so they do not discourage any of the outcomes that Beyond Tuition encourages.

- Accreditation agencies: Assess key elements of academic quality and conduct deeper dives into why institutions come up short on outcome measures. These assessments would be repeated periodically to ensure that the institution continues to offer a good return on students’ time and financial investment. Assessments would include input from previously enrolled students as well as faculty and industry experts, where applicable.

Though students would not sign these performance contracts, they too would be expected to be a partner to these agreements by providing any required family contribution and maintaining academic progress toward their credential to the satisfaction of their school.

The following sections provide a more in-depth discussion of each party’s obligations.

Institutional role

Each institution participating in Beyond Tuition would be held to performance benchmarks. These would include measures of access, such as the percentage of low-income students enrolled; measures of completion, such as the withdrawal rate or the graduation rate; and measures of post-school success. Because this system anticipates a dramatic reduction in student debt, post-school measures would focus not on loan repayment but on the percentage of students who earn enough above the poverty line to have family-sustaining wages. Institutions would also be expected to undertake efforts to keep their cost of delivering the education from growing too fast—a condition that builds on existing incentives in the structure of the affordability promise.

There are three key additional elements to this set of benchmarks that are particularly important: (1) demographic groups, (2) tailoring, and (3) tiered consequences.

Demographic groups

All measures would be assessed at the institutional level, but schools would also have to meet benchmarks for key populations. At a minimum, institutions would have to assess results by race or ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status. These groups are a reasonable starting point because the Department of Education already collects data on enrollment and completion by race, ethnicity, and gender, while its administrative data systems have data on outcomes for low-income students. Over time, institutions, accreditors, and the federal government should work together to consider whether to add additional groups of students.

Tailoring

Institutions would be categorized based on factors such as the type of institution, their historical mission, and the demographics of their student body. Each category of institutions would share a set of targets. Institutions that feel they are mischaracterized could appeal to be recategorized. The U.S. Department of Education’s statistical arm already does a form of this comparison grouping through something known as a Data Feedback Report.54 This grouping approach provides a way to tailor expectations for schools instead of using statistical methods to adjust schools’ results based on their characteristics—a process that is mathematically sound but means institutions cannot clearly predict what their regression-adjusted outcomes will be. This grouping process also ensures that institutions would not be judged against an unfair group of peers—such as a community college being held to the standards of an elite nonprofit institution.

Tiered consequences

Schools would face an increasingly strong set of consequences the further they fall from benchmarks or the longer they continue to fall short. Failure to address challenges on the equity audit over time would also result in similar consequences. The idea is that a school that only slightly misses a target—such as coming up a couple of percentage points shy in a single year—should not face the same consequences as one that misses by 30 percentage points multiple times. The proposed consequences are as follows:

- Slight miss: Disclosures to students and the public.

- Moderate to substantial miss: Increases in the state or institutional matching rate required to receive federal funds and creation of a detailed plan submitted to the federal government and accreditors of how to improve.

- Multiple years of unacceptable misses: Loss of federal financial aid eligibility.

This ladder of consequences is designed to provide institutions with the appropriate time and incentives to improve. After all, graduation rates are tracked over several years and thus take time to register improvements. Meanwhile, institutions that far exceed their benchmarks would be eligible for bonuses paid in the form of higher federal matching rates.

From the institutional perspective, this system presents an accountability structure that is more rigorous but also fairer than the one used today. Institutions would have several years to improve, be held to more tailored standards, and face a more flexible set of consequences. Coming with a substantial increase in federal postsecondary investments, this system would ensure that institutions have the opportunity and resources to deliver the education students deserve.

Federal role

The biggest federal commitment in a performance contract is that it will maintain the funding needed to make the program work at the established matching levels. This includes a promise to take on a higher percentage of costs if a state enters a recession. The federal government would also set benefit levels for nonacademic expenses such as food, housing, and transportation in order to control costs.

Beyond providing funding, the federal government will oversee performance contracts. The first step would be creating consensus definitions for measures of access, completion, and post-school success, as well as determining what demographic groups to track. The Education Department would also create comparison groups for colleges and set benchmarks for each one. The National Center for Education Statistics conducts similar consensus-building sessions with experts for its current data collections, so this role would be well within its current scope of work.

After this upfront development, the Education Department would then enforce accountability requirements. This would include negotiating with schools on the proper comparison group, enforcing consequences if a school comes up short, and adjusting the match rate as necessary. Comparison groups would be re-evaluated infrequently, unless a school’s structure changes significantly.

State role

Similar to that of the federal government, states’ biggest role in a performance contract would be providing necessary funding. This binding requirement ensures that states could not cut funding whenever budgets tighten. States would also be expected to ensure greater equitability in the levels of support provided to all types of colleges, moving away from the current system that invests disproportionately in more selective research universities while starving regional public and community colleges and minority-serving institutions.55

Beyond providing funding, states have one other main role: Ensure that their own accountability requirements align with federal benchmarks. Many states have adopted systems that tie some amount of state support to institutional performance. States could still maintain those performance-based funding systems, but they would have to ensure that measures and metrics would not work at cross purposes from any federal goals or perpetuate equity gaps. For example, if the federal government sets goals for access, a performance funding system should not encourage schools to become more selective.

Accreditor role

The accreditor role in a performance contract is to evaluate educational quality and to conduct deeper dives when institutional outcomes are not up to par. Accrediting agencies would agree to conduct detailed reviews of institutions’ academic programs to ensure they are assessing and providing clear disclosures of learning outcomes, are tracking graduate and employer satisfaction, and are building employer feedback into programs where appropriate.

If institutions struggle on federal performance measures such as graduation or retention, accreditors would conduct in-depth reviews to identify why a school is missing the mark and would offer recommendations to fix the problem. These requirements represent a clearer set of expectations of what accreditors should consider in their reviews than the current system. It also provides valuable support to institutions, particularly those that may not have the capacity to conduct in-depth reviews. Accreditors’ success in helping institutions address identified issues would then be considered when the Department of Education reviews them.

Benefits of this approach

This contract-based approach improves upon the existing federal accountability in many ways. While current accountability mechanisms tend to rest on just a single outcome measure and target only the worst performers, this system:

- Considers multiple measures of student performance, including access, completion, and post-school success.

- Measures institutions both overall and for results of key groups, including by race or ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status.

- Creates tailored performance targets that take into account a school’s demographics and historical mission while still setting ambitious goals.

- Establishes a graduated and predictable set of consequences beyond the current binary structure of being in or out of the federal financial aid program.

This strong backbone will ensure that the significant investments in affordability and quality result in a postsecondary education system that truly promotes equity.

Conclusion

Several times in its past, the federal government recognized the importance of expanding education to boost opportunities for disenfranchised and marginalized Americans. This effort started with the move to universal high school in the early part of the 20th century.56 Following World War II, the United States embarked on a broad expansion of affordable postsecondary education that made America one of the best-educated countries in the world.57 But those college opportunities were not equitably distributed, especially for people of color.58

The ability to access and complete college is still strongly attached to familial wealth and the color of one’s skin. Society’s failure to close these gaps is all the more devastating now, as the rewards of economic growth are increasingly limited to those with a college education.

Postsecondary education must be a major public investment if policymakers are looking to promote a productive economy and a highly skilled workforce. When the federal government, states, and institutions all invest in America’s students to ensure affordable, high-quality options exist for all, everyone wins.

Beyond Tuition would revolutionize higher education. It would curb escalating costs, stop the retreat of state funding, and give families certainty that they could afford the total price of college without drowning in debt. Such an effort would begin to address historic and systematic discrimination, putting a quality college education within reach for all Americans—regardless of race or income. All Americans have the right to a postsecondary education regardless of who they are or where they come from, and Beyond Tuition is a means to guarantee every person has the opportunity to attain a prosperous future and to be part of a flourishing democracy.

About the authors

The Postsecondary Education Team at the Center for American Progress advocates for solutions to improve equity, affordability, accountability, and quality in higher education.

Appendix