Introduction and summary

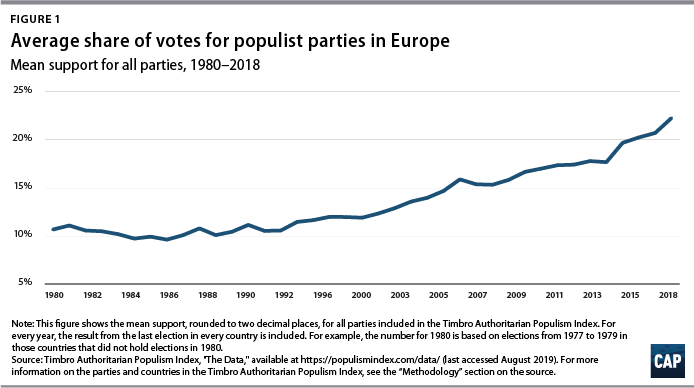

Since 2016, concern over the resurgence of illiberal populist political parties and movements has been palpable in Europe and the United States. The election of Donald Trump, the United Kingdom’s referendum to leave the European Union, and the electoral advances of far-right parties in many European states, including France and Germany, created the sense that populist parties were a new, unstoppable political force in democratic politics.1 Yet in 2019, the notion that populist parties are the future of European politics seems far less certain.

The term “populism” itself may have outlived its usefulness. Originally, it referred to parties and leaders who described themselves as true voices of the people against self-serving, out-of-touch elites—and it was prone to run roughshod over established political norms and institutions. Over the past three years, differences in approaches, tactics, and outlooks between different populist parties have emerged, making it clear that there is no clear populist governing strategy. Accordingly, beyond disrupting the current order, anti-establishment political forces in Europe share no actual transnational policy agenda. Yet populist and anti-establishment forces have upended European politics and contributed to fragmentation and uncertainty. As the example of the record turnout in the 2019 European parliamentary election illustrates,2 the EU itself has become an important dividing line for voters.

The high turnout and raucous nature of the 2019 election portends animated debates over European policies. Gone are the days when the EU could move initiatives forward without much public attention or concern. In short, Jean Monnet’s “salami-slicing” method of incremental, technocratically driven European integration3 is dead. A more engaged and aware European public is in itself a positive development. Yet simultaneously, for better or worse, the sudden salience of European policies can present an obstacle to policy initiatives that otherwise would be seen as uncontroversial. Just as partisan divisions in the United States have plagued Washington with significant policy paralysis, the emergence of a similarly contentious and partisan politics in Europe may make it hard for Brussels to act.

Europe has proven resilient over the past decade, but that resilience should not be taken for granted. The EU largely has failed to address its structural weaknesses that were exposed following the 2008 financial and fiscal crisis, meaning that the EU would confront a future economic crisis with the same limited toolbox it had in 2008.4 To make matters worse, influential populist actors could also obstruct swift action while benefiting politically at home from the EU’s failings. Unlike only a few years ago, fears of the EU’s sudden unraveling seem farfetched. Yet a protracted death by a thousand cuts, caused by populist leaders undermining EU rules and norms, remains a distinct possibility.

The new instability of European politics poses a real challenge to the trans-Atlantic alliance. Unity among free and democratic states of the West is hard to sustain in the current political environment on both sides of the Atlantic. Yet at a time when the alliance faces a rising challenge from autocratic powers such as China and Russia, the case for unity and cooperation is stronger now than at any point since the end of the Cold War. This report seeks to chart a course for the EU and for the trans-Atlantic alliance, while acknowledging that the anti-establishment sentiments that reverberate through European politics are here to stay. While there is a strong case to be made for a Europe that works together to defend democratic values at home and abroad as well as a trans-Atlantic alliance that is willing to work in proactive partnership to tackle big global challenges—from climate change to terrorism to nuclear proliferation—that goal is still a long way off.

Fragmentation, polarization, and the realignment of the political mainstream in Europe

Much has been made of the seemingly inevitable rise of authoritarian politics in Europe, but the true picture in Europe today is far more complex than what such generalizations allow. In analyzing this complexity, what becomes apparent is that this disruption to so-called traditional politics includes not only authoritarian political movements but also new forms of moderate politics, as well as adaptation by traditional center-left and center-right parties. In this report, the authors look at four specific trends: the fragmentation of traditional political alliances; the emergence of a new liberalism countering authoritarianism; the divergent revivals of social democratic parties; and the radicalization of traditional conservatism.

Fragmentation of the European Parliament

The run-up to the 2019 European parliamentary election was dominated by the expectation of an inevitable rise of populism across the continent.5 The results of the election, however, did not live up to the hype, with media coverage of the far-right nearly evaporating since the election.6

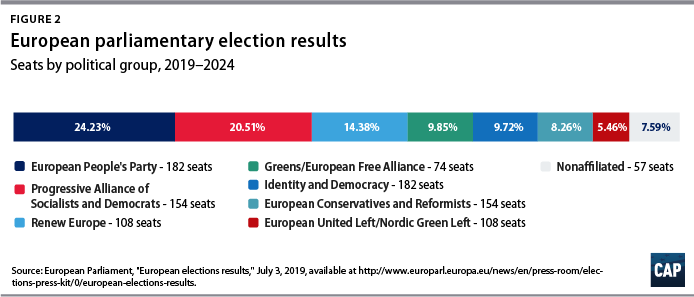

While a populist takeover of the European Parliament did not happen, populists on the far-right did grow in strength. Far-right populists now hold almost 25 percent of all seats in the European Parliament.7 This result reflects the strength of Matteo Salvini’s Northern League in Italy and Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in France as well as the radicalization of some traditionally center-right parties such as Fidesz in Hungary. In the United Kingdom, the floundering UK Independence Party (UKIP) was replaced by Nigel Farage’s new Brexit Party, which took a significant share of the vote from both the Labour Party and the Conservative Party.

Left-wing populists fared significantly worse in the 2019 election than they did in that of 2014. In 2014, there was significant energy behind insurgent left-wing parties such as Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece.8 The two parties’ underwhelming performance this year reflects a decline in their domestic political positions. Over the past five years, both parties also became far more tempered in their positions on European policies. Similarly, other left-populist parties, including the Unbowed movement in France and the old Socialist Party in the Netherlands, failed to make a sizable national impact. Neither did traditional social democratic parties that had veered to the populist left, such as Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party in the United Kingdom or the German Social Democrats under Andrea Nahles, perform well. In the case of UK Labour, the party’s ambiguity over Brexit played a key role in its performance, as the election served as a second referendum of sorts regarding the United Kingdom’s membership in the EU.9

The election has heralded a complex political environment for the EU, characterized by increased fragmentation across the political spectrum and no clear majority in favor of any one direction. In this regard, the outcome is a continuation of a trend identified initially by political scientist Cas Mudde in 2014:10 The emergence of new insurgent parties on the right, combined with the growth of support for liberal and green parties, has further weakened the position of the traditional center-right and conservative blocs that once controlled the European Parliament.

The 2019 European election can be seen as a “split-screen” vote.11 As Susi Dennison, Mark Leonard, and Paweł Zerka of the European Council on Foreign Relations note, voters “rarely used their vote to endorse the status quo,” yet wanted radically different forms of change. The resurgence of green parties across the continent during this election, for instance, reflects a desire among some segments of the electorate to address climate change more aggressively. Other voters, in contrast, are more concerned with the rise of right-wing nationalism and xenophobia, which explains the growth of some liberal parties. While the growth of liberal and green parties is in some ways a reaction to the gains of the far-right, it also suggests that the European Parliament—and European institutions more broadly—will face difficulties settling on a coherent policy agenda for the next five years due to their disparate priorities.

Europe’s large political families, the European People’s Party and the Party of European Socialists—which both saw a decline in their share of the vote—cannot avoid working with some of the new liberal and green parties. At least in the European Parliament, the next five years will not be characterized by dominance of the far-right, but rather by a fragmented political landscape in which new alliances will be necessary to keep the EU’s traditional agenda moving forward. This will not be an easy task. Both inaction and the inability to compromise on some of the most important reform agendas are possible outcomes, at least in the short term.

The fragmentation of the political order at the European level is also mirrored by similar trends across the EU’s member states. This is not surprising, as political realignments at the national level are both consequences of and contributors to pan-European trends. National politics is thus becoming, slowly but surely, Europeanized, and Europe itself is becoming a central political issue in national debates.

A new liberalism: Centrism and grand coalitions

At the end of 2018, commentators were setting the stage for a battle of ideas between illiberal nationalism and reform-minded pro-Europeanism that was expected to dominate the campaign ahead of the European election. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and French President Emmanuel Macron made for natural leaders of these two political camps.

Orbán’s speeches on making Europe great again in Brussels in January 201712 as well his speech in memory of former Chancellor of Germany Helmut Kohl in Budapest in January 2018 positioned him as the leader of nationalist forces in Europe and across the globe.13 President Macron’s sound electoral victory over Le Pen in May 2017, in contrast, widely was seen as a model for how illiberalism and nationalism could be defeated. As early as October 2017, Macron’s political party La République En Marche! began establishing relationships with what they hoped would be the founding partners of a new political family in Europe, starting with the pro-business centrist party Ciudadanos in Spain.14

Thus far, attempts to create new pan-European political families have proven more difficult than expected—and not just for Macron. Salvini’s goal of creating a far-right “League of Leagues”15 and U.S. far-right political operator Steve Bannon’s attempts to create a populist club called The Movement16 both floundered.17 Ultimately, Macron’s pan-European campaign ahead of the 2019 election amounted to little more than a call for a European “Renaissance” articulated in a syndicated opinion column published across the continent.18 Macron’s failure to build a new centrist movement had domestic roots: The sustained protests by the yellow vest movement ensured that Macron’s political capital and attention had to be focused elsewhere, as Ismaël Emelien—Macron’s long-term strategic adviser at En Marche! and at the Élysée—notes below in his contribution to this report. Over a period of several months, Macron’s government witnessed a significant decline in the polls.19 In response, his team launched a “grand débat,” where the president toured the country and engaged in town hall conversations with citizens. Gradually, Macron’s handling of the crisis saw his approval ratings rise, and his reengagement with the public seems to have reassured his supporters. Whatever Macron’s electoral prospects may be—and it seems unlikely that the yellow vest movement will lead to either a resurgence of the left or a strengthening of the conservative movement—Europe has seen pro-European centrist movements and coalitions organize themselves to push back against nationalism and illiberalism, oftentimes inspired by Macron’s early success.

Analysis: President Macron and the gilets jaunes

By Ismaël Emelien

For more than eight months, the world has been accustomed to weekly images of riots in France. Saturday after Saturday, people wearing yellow vests as a rallying sign engage in protests and, in the case of several thousands of participants, in violence.

This of course opens up a lot of questions.

First, is France going through another of its many political revolutions? Clearly not. At the peak of the mobilization, a little less than 400,000 individuals gathered wearing yellow vests, not even entering in the top 10 of the biggest social movements in France since 2000. But at that time, polls showed that roughly 70 percent of the French population was in favor of the movement, making it one of the most popular of the past decade—though this was before violence took over. So, the yellow vest movement is not a revolution, but it is clearly something worth considering.

Second, is it good news for President Macron’s opponents? Not really. The left was hopeful for the first weeks, when the yellow vests were demanding more public expenses and more redistribution. The same movement has also demanded more economic opportunity and lower taxes—the protests were triggered by an increase of the gas tax, after all. The right convinced itself that this was a beginning of a cultural and identity mobilization. Yet, the yellow vest protesters were not mobilizing against same-sex marriage or immigration but rather for economic and social mobility. The European parliamentary election was a perfect illustration of where such misconceptions lead: Combined, the Socialist Party and Les Républicains went from receiving 25 percent of the votes in 2017 to 15 percent in 2019. The situation for Marine Le Pen’s National Front (FN) or National Rally is similar. On the one hand, yellow vest protesters did express very strong anti-establishment opinions and proved to be extremely fond of conspiracy theories, playing into the populists’ hand. But on the other hand, they explicitly distanced themselves from the FN and defeated each of the many attempts this far-right party made to absorb them.

Third, and last, what does this mean for President Macron? First, he was right from the beginning in his diagnosis of the French situation: The two mottos of the yellow vest protesters, “Neither left nor right” and “We want work to pay” were the pillars of his presidential campaign. Second, Macron is seen as not yet delivering on his campaign promises, since two years after the election, those issues remain acute. For Macron, it may actually have been good timing, as the protests provided a wake-up call: With a strong majority, a loyal government, approval ratings on the rise, the success of the grand débat, and good electoral results, everything he needs to address the root cause of this unprecedented social mobilization is there.

Ismaël Emelien is a co-founder of En Marche!. He is the former chief strategist of Macron’s presidential campaign and senior communications adviser in the Élys

In Poland, for example, a new pro-European and pro-democracy alliance has emerged in the form of the Civic Coalition, founded by the center-right Civic Platform and the liberal Modern parties ahead of the 2018 local election. Three-and-a-half years of a one-party government, the Law and Justice Party (PiS) led by Jarosław Kaczyński, saw numerous assaults on the country’s constitutional order and created a new sense of urgency for the opposition.

The European election provided a testing ground for collaboration for pro-democracy forces ahead of the Polish parliamentary elections in November 2019 and the presidential election in May 2020. In February 2019, nearly every moderate party that opposed PiS—from the conservatives to the Greens—combined forces into a common electoral list extending beyond the Civic Coalition.20 The new European Coalition’s platform was simple: to protect democracy and the rule of law and lend support to Poland’s place in the EU. The coalition’s campaign kicked off with the support of the liberal Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) Party in the European Parliament in April with much fanfare.21 In a context where the government had created a climate of us vs. them, dividing the country into two Polands—one based on solidarity and the other supposedly on unchecked social and economic liberalism—the opposition sought to recast the battle as one about the defense of democracy and pluralism.22

Yet the run-up to the election was characterized by a number of sex-abuse scandals in Poland’s powerful Catholic Church. Instead of eroding support for the culturally conservative PiS, the debate reinforced a siege mentality among PiS’ rural and traditionalist electorate not dissimilar to the “Flight 93 election” mentality—“charge the cockpit or you die”—observed in some conservative circles in the United States.23 The European election confirmed the deep geographic divides existing within the Polish electorate and the firm grip that PiS still exercises over its traditional strongholds. It remains to be seen if the opposition parties can improve on their results in the parliamentary election in fall 2019. The dynamic might be particularly interesting if the Civic Coalition is no longer the only game in town. In particular, Wiosna (“Spring” in Polish), a new, explicitly progressive party, has provided an alternative for liberal urban voters. Established by Robert Biedroń, the mayor of Słupsk and a famous LGBT rights campaigner, Wiosna—the only independent party not aligned with any of the major political families—managed to win 6 percent of the vote in the European parliamentary elections, earning 3 out of Poland’s 51 seats.24

The developments in Slovakia offer interesting parallels, as well as some differences, to those in Poland. Following almost a decade of governments led by Robert Fico’s Smer, a left-populist party, the energy seems firmly on the side of centrist, pro-EU forces. The current developments have been catalyzed by the public’s reaction to the murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancé Martina Kušnírová in February 2018, as Kuciak was working on a story exposing the ties between Slovakian politicians and the Italian mafia.25 The killings led to Fico’s resignation from the presidency though not from the leadership of his party. The slow and half-hearted beginnings of the investigation into the murder led to a new generation of political activism among people who had come of age after communist rule. A generation that had grown up in a democracy that their parents had fought for, one young protestor told The New York Times, owed it to their parents “to win the fight against corruption.”26

Two new centrist, pro-European parties have been the main beneficiaries of these developments: the center-left Progressive Slovakia (PS) and the center-right SPOLU-Civic Democracy. The coalition of PS and SPOLU ranked first in the European election, defeating both Smer and a long list of established opposition parties. Even more significantly, the focus of the new political movement on defense of the rule of law and environmentalism led to the election of the country’s first female president, Zuzana Čaputová. Čaputová, who was sworn into office on June 15, 2019, has long been a vocal government critic and anti-corruption activist who first garnered attention for successfully campaigning against a planned toxic landfill in her hometown of Pezinok. She has been nicknamed Slovakia’s Erin Brockovich27 for her leadership of this campaign, which she was inspired to take up after learning of cancer diagnoses of people close to her. She eventually won the case before the European Court of Justice in 2013.28

Čaputová is proudly European in values and supportive of the Europe integration project. Like Poland’s Biedroń, she supports minority and LGBT rights, including the adoption of children by same-sex couples. Strikingly, she is perhaps the first major politician in Slovakia, if not in central Europe, to articulate her distinctly liberal positions in a manner that many conservatives and Christians in the country find nonthreatening, basing her arguments on conservative and Christian values of empathy and respect for other people.29

Aside from new pro-European liberal movements in central Europe, unprecedented centrist coalitions of traditional parties have started to emerge in other parts of the continent. In Sweden, for example, for the first time ever, the traditional blocs of left and right—led respectively by the Social Democratic Party and the Moderate Party—have given way to a new political order. The results of the Swedish general election in September 2018 were inconclusive. The incumbent minority government, consisting of the Social Democrats and the Greens and supported by the Left Party, won 144 seats—just one seat more than the four-party Alliance coalition, which brings together the Moderate Party, Centre Party, Christian Democratic Party, and the Liberal Party. The remaining seats went to the far-right Sweden Democrats.30

In the resulting hung parliament, it took four months of intense negotiations to build a government. Because the Alliance coalition had ruled out governing with the Sweden Democrats before the election began, they proved as incapable of forming a minority coalition government as the Social Democrats and Greens. Finally, on January 1, 2019, the Social Democrats, Greens, Centre Party, and Liberals struck a deal whereby the Social Democrats and Greens would form the government with the parliamentary support of the Centre Party and the Liberal Party, which do not hold ministerial positions in the government.

This new political settlement has been the topic of much debate, not least among conservatives. As Karin Svanborg-Sjövall and Andreas Johansson Heinö from the Swedish think tank Timbro note in their contribution to this report, it is unclear whether the country’s conservatives can return to power without the support of the Sweden Democrats.

It is an open question whether this is the beginning of a new era of Swedish politics or a temporary blip before a return to a competition between right- and left-wing political blocs, albeit characterized in a new form. While the governing agenda has been supported by trade unions and members of the left, Social Democrats have voiced concerns about whether the arrangement is sustainable. Such calls were amplified following the proposed tax reforms, which were seen as benefiting high-income earners in the coalition’s first budget. It remains to be seen whether this new traffic-light coalition will provide the foundations for a new progressive alliance in the manner advocated by Matt Browne, Ruy Teixeira, and John Halpin in a 2011 CAP report, which called for a coalition of Social Democrats, Liberals, and Greens to ensure a continued progressive hegemony in the new fragmented European landscape.31

Social democratic revivals

Following the global financial crisis in 2008, and then again in the aftermath of the European refugee crisis in 2015, social democratic parties suffered a string of electoral defeats. Only a decade earlier, some 14 out of 15 member states of the EU were governed by social democratic parties or coalitions led by them. By 2010, that ratio had dropped to 5 out of 27 member states. Social democratic parties have since found themselves caught in a pincer movement between urban-value voters, who commonly favor lower taxes and an embrace of openness and multiculturalism, and their traditional working-class base, which tends to favor restrictions on immigration. Responding to these pressures without jeopardizing the goals of progressive politics has become increasingly difficult.32

Analysis: Where now for Swedish conservatism?

By Karin Svanborg-Sjövall and Andreas Johansson Heinö

“We haven’t chosen this, but our opponents have really forced us into an existential fight for our culture’s and our nation’s survival. There are only two options: victory or death.”33

A normal party would not resort to such fateful rhetoric to console its supporters following a nearly 5 percentage-point increase from the previous election, especially not after it had achieved a long-term strategic goal of splitting classically liberal parties from conservative parties—a goal that the Sweden Democrats thought would get them closer to the political and legislative power they had been denied for so long.

But Sweden’s third-largest party, the Sweden Democrats, is not like the others. When the author of the above quote, the group’s leader and chief ideologue Mattias Karlsson, became active with the Sweden Democrats in the 1990s, the party still had connections with neo-Nazis. Since Karlsson and the party leader Jimmie Åkesson had been responsible for the party’s electoral success by gradually moving its position from authoritarian chauvinism to a softer, more socially conservative position, many were surprised by his choice of words.

Opinions within the Swedish right are divided on the extent to which the Sweden Democrats have actually reformed. Neither is there agreement about how their electoral success should be managed—through continued isolation or through limited legislative cooperation. That question has plagued Swedish politics for almost a decade. When the party entered the Swedish Parliament in 2010, the traditional left and right blocs were no longer able to hold a majority on their own. As a result, the governing center-right coalition’s term was near-paralyzed. After the 2014 election, the Sweden Democrats struck down the newly elected left coalition’s budget proposal. Following the threat of a snap election by the Social Democratic Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, the “December Agreement” was struck, meaning the traditional party coalitions would accept the largest party grouping’s budget proposal. This compromise received intense internal critique on the right and fell apart after less than a year, but the left-leaning government was still able to carry out its full term.

Following the record-long process of building a government after the 2018 elections, there was a political compromise between the red-green left government and the two liberal right parties in Parliament. Due to a growing polarization between classically liberal and conservative parties on the right, the traditional nonsocialist coalition has ceased to exist. The left-leaning government is now forced to implement parts of their opponents’ free market policies, while the two conservative parties—who campaigned in favor of the same issues—now find themselves in the opposition with the Sweden Democrats and the former Communist Party.

This unconventional political constellation seems remarkable in light of the significantly diminished policy discrepancies between the Sweden Democrats and other parties. After the refugee wave of 2015, when Sweden accepted approximately 160,000 people in one year, broad support for a more restrictive migration policy began to emerge. On economic policy, the Sweden Democrats—previously in favor of a generous welfare system—have become more conservative in their views on taxes and business.

Despite a shift in policy, the Sweden Democrats are unreliable when it comes to security policy and diverging from the open nature of Swedish political discourse that a small, export-dependent country embraces. Time after time, the party demonstrates a flagrant lack of respect for the separation of powers and independent institutions, the freedom of the press, and the right of cultural institutions to be independent from political influence. There are still major fundamental obstacles for the established parties, not least within the (so far) liberally dominated right wing, to enter into an organized collaboration.

However, looking forward, it’s difficult to see how a party with almost 20 percent support can be held back from political influence in the long term, especially if the only alternative is a Social Democratic prime minister who is barely tolerated by Parliament. Within the traditionally conservative parties, there is a strong desire to compete with Sweden Democrats for votes. Therefore, it would be important for the established parties to take up the task of strengthening Sweden’s weak constitution and defining the lines between policies that can be negotiated with an illiberal but ultimately democratic party and the rights that should be out of reach for any political majority. Making the Sweden Democrats part of the government, however, remains—and should remain—unacceptable.

Karin Svanborg-Sjövall is the CEO of Timbro, a Stockholm-based think tank. Andreas Johansson Heinö is the head of publishing at Timbro; president of Sture Academy, Timbro’s program of political education and training; and the creator of Timbro’s Authoritarian Populism Index.

For some, the transformation of the Danish Social Democrats is seen as a model for how to hold together different constituencies within the traditional social democratic coalition. Following their defeat in the 2015 elections, during which they remained the largest party but lost out due to the weakness of their formal coalition partners, the Social Democratic Party’s new leader Mette Frederiksen decided to undertake a radical reevaluation of the party’s policy on immigration. The party undertook a mass consultation of party members on policy challenges and priorities, which led to a sweeping revision of the party’s positions on migration and asylum. The Social Democrats adopted a tougher stance on illegal migration but matched it with greater investment in development financing and more policies to support the integration of immigrants into Danish society.34 The party also embraced more interventionist economic policies and in its election campaign promised to improve the social safety net and welfare payments for working-class families.35

These policies have been met with mixed reviews within the progressive family. Some have accused the party of ceding too much ground to the populist right, while others have interpreted the new approach to migration as a recognition that defending the values of an open society requires the protection of borders and clear definition and expectations of the rights and responsibilities of its members. The University of Oxford economist and noted immigration skeptic Paul Collier argues that the Danish Social Democrats have shown how to renew European social democracy by rebuilding a culture of shared identity, common purpose, and mutual obligation.36 Under either of the two interpretations, Frederiksen’s approach seems to have worked: Following the left’s victory in the election in June 2019, Frederiksen became the country’s youngest-ever prime minister.

This path to a social democratic revival is markedly different from that seen in the Iberian Peninsula. Over the past decade, the rise of Podemos on the left and the centrist Ciudadanos undermined the dominant role of the traditional social-democratic Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and the conservative People’s Party (PP) in Spain. At the same time, Spanish politics have become more volatile. First, the vitriol of Catalonian separatism intensified following separatist leaders’ illegal decision to hold a referendum in October 2017, which led to the suspension of the region’s autonomous rights for seven months and the arrest of separatist leaders.37 Second, a series of corruption scandals rocked the establishment PP, leading to a vote of no confidence in the government and the removal of Mariano Rajoy as prime minister in June 2018.38

Following the vote of no confidence, Pedro Sánchez, leader of the PSOE, became the new prime minister. Many assumed that his term would be short-lived. Sánchez, however, built a strong cabinet populated by experts and a historically high proportion of women—the first majority-female cabinet in Spain’s history. Meanwhile, a new and unanticipated competition began to emerge for leadership of the right between Ciudadanos and the PP. Both parties began to take an increasingly hard line on Catalonia as opposed to Sánchez, who sought compromise. This competition was further complicated by the rise of a new party on the far-right, Vox. The anti-European and chauvinist nationalist party quickly gained support through its visceral criticism of Sánchez’s decision to welcome North African refugees who were refused entry by other European nations.39

By November 2018, most polls suggested that Spain was drifting to the right. Vox’s success in the Andalusian regional election, which allowed Ciudadanos, the PP, and Vox to form a center-right coalition, confirmed this trend. The result sent shock waves through the political establishment for two reasons: Andalusia was formerly a PSOE stronghold, and the far-right had entered a government for the first time since Spain’s transition to democracy.40

In March, ahead of the parliamentary election, Ciudadanos’ leader Albert Rivera stated that under no circumstances would he consider joining the PSOE in a coalition.41 While Rivera may have been forced into this position by circumstances, as he was trying to ensure that Ciudadanos would become the largest party on the center-right, it proved to be a misstep. Sánchez and the PSOE successfully reframed the election as a referendum over the return of fascists to the national government in Spain, represented by a coalition between Ciudadanos, the PP, and Vox. Sánchez thus consolidated votes on the left and the center around a progressive economic agenda, Spain’s openness to migration, and the EU.

Since the election, Rivera has doubled down on his insistence that Ciudadanos will not cooperate with the PSOE under any circumstances. This has been a source of some consternation for his European partners, notably President Macron, who is supportive of such collaboration.42 More recently, within Ciudadanos itself, this electoral strategy has become problematic. A number of senior advisers—including Toni Roldan Mones, the architect of the party’s moderate economic policy—have resigned because of Rivera’s position. Indeed, many political commentators now argue that Rivera has shown that Ciudadanos is no longer a liberal party espousing free markets and pro-growth reforms but rather an intolerant force willing to serve the goals of the far-right.

Far-right colonization of the center-right

Ciudadanos’ political trajectory described above illustrates two trends in European politics: the radicalization of mainstream conservatism and radicals’ hostile takeovers of center-right parties.

The transformation of Orbán’s Fidesz from an anti-communist and mainstream pro-European liberal party in the 1990s to an anti-European authoritarian party today is well documented. Under a different set of circumstances, the Christian Social Union in Germany sought to defend its dominance in Bavaria against the populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) by moving to the extremes on immigration. Yet it is the radicalization of the British Conservative Party over Brexit that may be the most consequential case in point for the future of Europe.

The British Conservative Party’s relationship with Europe has long been troubled. However, the decision by then-Prime Minister David Cameron to hold a referendum on Britain’s membership in the EU in 2016 has had a profound effect on the future of his party, the country, and possibly the EU itself. The referendum provided a national platform for right-wing, anti-European Nigel Farage, who at the time was leader of the UK Independence Party (UKIP). Farage’s party gained the largest share of the vote in the 2014 European election.43 Although voter turnout was low, many saw this victory as a determining factor forcing Cameron’s hand to promise an in-out referendum during the 2015 general election.44

Although the majority of the Conservative Party’s members of Parliament supported the “remain” campaign, several charismatic figures such as then-Conservative Party leader Boris Johnson broke with this position. In the aftermath of the 52-48 vote in favor of Brexit, Cameron resigned, and Theresa May, who voted against Brexit, emerged as the only candidate in a race to succeed him as prime minister. Upon taking office, May triggered Article 50, the act to leave the EU, and called a national election to gain a mandate to deliver. The move cost May her majority in Parliament and forced her into a coalition with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) of Northern Ireland.

May then concluded a withdrawal agreement with the EU, for which there has been no majority in Parliament. The DUP has been unwilling to accept the Irish backstop—a deal wherein the EU secures no hard border in Ireland—which it sees as a step toward the separation of Northern Ireland from the rest of the United Kingdom and the possible reunification of Ireland. Meanwhile, the hard-line anti-EU Movement for European Reform in the Conservative Party argues that only a “no-deal” Brexit genuinely delivers on the result of the 2016 referendum, notwithstanding many prominent Brexiteers’ earlier claims to the contrary. The resulting deadlock led to May’s resignation in May 2019, a delay to Brexit, and a huge opening for an insurgent far-right populist force. In the European elections, Farage’s new Brexit Party seized that opening, capitalizing off the turmoil within the Conservative Party and winning more than 30 percent of the vote.

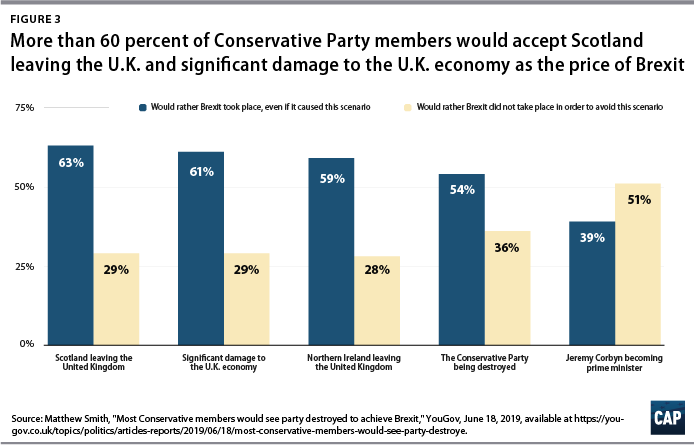

The radicalization of Conservative members of Parliament over Brexit reflects the rising challenge from UKIP and the Brexit Party. It also illustrates how the Conservative Party’s membership has shifted to the right both in composition and ideology. The recent growth in membership of the Conservative Party from 100,000 to 160,000 members was driven in part by the influx of former UKIP members, with some estimating that as much as 43 percent of the current party membership comprises former UKIP voters or members.45 This compositional shift also indicates the party’s ideological move toward the far-right. As shown in a recent poll, the majority of Conservative Party members would happily accept Brexit even if it were to lead to Scotland and/or Northern Ireland leaving the United Kingdom, the demise of the Tory Party, and/or a massive economic shock to the British economy.46 (see Figure 3) The only outcome for which they would not trade Brexit is the prospect of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn becoming prime minister.47

In this context, it is perhaps unsurprising that Johnson emerged as the next prime minster of the United Kingdom. Johnson has already indicated that he would ignore a vote of the House of Commons to prevent a “no-deal” Brexit. Whether this would lead to a closure of Parliament or an early general election in which the Conservatives form an alliance with Farage remains unclear. What is beyond doubt, however, is the striking degree to which right-of-center politics in the United Kingdom have been reduced to a rejection of the European project, reflected in the hard-line Brexiteer stances of the leading members of Prime Minister Johnson’s first cabinet.

Taken together, the above three trendlines speak to a general disruption of postwar politics in Europe rather than the emergence of a new set of orthodoxies. The differences within the traditional political families—be they social democratic, conservative, or liberal—are often as great as those between them. Similarly, the emergence of new centrist coalitions or forces in domestic politics owe as much to specific local circumstances as they do to a coherent, shared ideological framework. This not only makes it difficult to derive lessons for those who might seek to emulate centrist electoral revivals or successes but also to predict how the major political families will work together to forge a transnational agenda in the current climate.

Populists in power

Notwithstanding the varied efforts by centrist forces to keep populist parties away from power, anti-establishment forces have gained power in a number of EU countries in recent years. Examples include Hungary’s Fidesz from 2010 to the present; Poland’s PiS from 2015 to the present; Greece’s Syriza from 2014 to 2019; Italy’s League and Five Star Movement from 2018 to the present; the Freedom Party of Austria from 2017 to 2019; the Finns Party in Finland from 2015 to 2017; and the Conservative People’s Party of Estonia from 2019 to the present. In other countries such as the United Kingdom and Denmark, populist parties have exercised significant influence over policies implemented by national governments, with the Brexit referendum being the most conspicuous example.

Yet these recent experiences of populists taking power are not completely unprecedented in Europe. In 2000, in a shock to much of the EU, the far-right Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) joined the Austrian People’s Party as a junior partner in a government coalition. The EU responded with a regime of diplomatic sanctions against Austria, but the coalition survived for another two years and was recreated after the early election of 2002, in which the FPÖ performed poorly, having had little effect on the country’s policies.

In Switzerland, the gradual rise of support for the Swiss People’s Party (SVP) resulted in the gain of a second seat in the seven-member Federal Council in 2003. In government and in the opposition, the SVP—which has become the largest party in the country—supported free-market economic policies, opposed the expansion of federal spending, and took a hawkish view on immigration policy, famously campaigning against the presence of Islam in Switzerland. Italy, too, has had ample experience with populist parties in government, including Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia from 1994 to 1995 and from 2001 to 2006; Partito della Libertà from 2008 to 2011 and in 2013; and Lega Nord, known today as the League, from 2008 to 2011, which predate the current turbulences that brought populism to the forefront of the debate.48

If the earlier presence of populists in European governments was episodic, the current iteration seems more consequential. The populist upsurge has been synchronized across Europe, if not across the democratic world. Unlike their previous successes, which reflected disparate local grievances, the current populist upsurge seems driven by a tension between nationalism, or parochialism, and the globalist, cosmopolitan outlook held by most political forces on the traditional center-right and center-left across the Western world. This political divide has also manifested itself geographically, with urban cities adopting an increasingly cosmopolitan, global outlook, while more rural areas adopt a more nationalist and reactionary stance.49 Populists in Europe have successfully mobilized their electorate in response to immigration as well as to the EU’s handling of the debt crisis that affected the eurozone’s periphery in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis.

But have populists in power been effective in shaping policy? And if so, how? Right-wing populists share a restrictionist view of immigration, made clear both in rhetoric and in policy practice. Hungary’s Fidesz government, for example, completed a barrier on the border with Serbia, a country seeking EU accession. Similarly, the fear of Muslim immigration brought the PiS to power in Poland and derailed the European Commission’s plan for a common relocation mechanism for asylum-seekers across the EU. Strikingly, neither Poland nor Hungary—where the radical, anti-immigration brand of politics has made significant strides—has direct experience with mass immigration from Muslim-majority countries. Immigration to Poland has been stable over the past decade and outweighed by population outflows over much of the same period.50 Hungary, in turn, is suffering from a pronounced brain drain, with as many as 600,000 Hungarians living in other EU countries out of a population of less than 10 million.51

While populist forces rejected the EU’s putative open borders policy, right-wing populists could not articulate a coherent, positive alternative. For example, on the important question of burden sharing, their interests visibly diverged. For populists in central Europe, the idea that their countries should in any way participate in the EU’s common response to the crisis was anathema. Populists in Italy, meanwhile, pointed out that the Dublin system—a European agreement that grants refugees asylum in the EU country in which they first arrive—imposed unreasonable demands on countries on the EU’s outer borders and allowed countries such as Hungary to free ride.52 Restrictionist rhetoric aside, it was ultimately the so-called establishment, not Europe’s populists, that brought the 2015 refugee crisis to a halt. It was the EU that negotiated an agreement with Turkey to close the flow of asylum-seekers through the Eastern Mediterranean. Likewise, it was the EU-Libya agreement that reduced the inflow of migrants into Italy—not the policies of the current governing coalition in Italy.53

Apart from questions of immigration, finding common patterns in the governing style of populists is more difficult. In Finland, the recent governing coalition—which was ousted in March 2019 and featured the initially far-right Finns Party—emphasized a fairly conventional free-market agenda in response to Finland’s poor economic performance and adverse demographic trends. The agenda featured cuts to public spending, especially to health care, combined with a liberalization of the labor market.54 The Austrian cabinet that collapsed in May 2019 had made pro-growth tax reform a centerpiece of its policy agenda,55 accompanied by a novel digital tax that is also being entertained at the EU level.56 In contrast, the Italian government—composed of nominees of League and the Five Star Movement—was built partly around its refusal to pursue economic reforms demanded by the troika of the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In Poland, the right-wing populist PiS expanded existing social assistance by creating new general entitlement programs such as the Family 500+ program, which added significantly to the country’s public debt.57 Hungary’s government has also enlarged the scope of its pro-natalist policies by creating a new housing subsidy for families.58 Both in Hungary and in Poland, these policies come on top of an economic agenda that seeks to favor domestic ownership at the expense of foreign investors.

Greece’s Syriza is a special case. The left-wing populist party arose primarily in response to the austerity measures that Greece adopted during the financial crisis and came to power with the explicit purpose of defying the troika. Following the referendum in July 2015, which said no to Syriza’s demands, the government was forced to change course—likely because the alternative involved crashing out of the eurozone. In subsequent years, the Syriza government implemented, in spite of its rhetoric, a substantial program of fiscal consolidation. The government was expected to run a primary budget surplus of more than 5 percent of GDP in 2019 before handing power over to the center-right New Democracy, whose leader, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, has made a pro-growth agenda of fiscal consolidation a centerpiece of his campaign.

Populism and authoritarianism

Because of their rejection of pluralism, populists style themselves as authentic representatives of the people, whom they treat as a homogenous mass.59 Seen through this lens, it is hard to appreciate the value of checks and balances, judicial review, independent public broadcasting, and other institutions constraining the power of the majority—hence the connection between populism and authoritarianism. It was no accident that in his speech on July 26, 2014, Orbán singled out Singapore, China, India, Turkey, and Russia as “stars of the international analysts today,” touted the idea of an “illiberal state,” and suggested that Hungary needed to part with Western European “dogmas,” especially with the liberal notion that people “have the right to do anything that does not infringe on the freedom of the other party.”60

After arriving in power, Hungary’s Fidesz introduced a new constitution known as the Fundamental Law, which came into force on January 1, 2012.61 It was drafted by a small group within Fidesz and adopted with Fidesz’s two-thirds majority in Parliament.62 From 2011 through 2013 alone, Parliament passed 32 so-called cardinal laws to amend the constitution.63 A 2013 constitutional amendment stipulates that the right of freedom of speech may not be exercised in such a way as to violate the dignity of the “Hungarian nation.” Another 2013 amendment took away the Constitutional Court’s power to review passed budget and tax laws once the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 50 percent. If, for example, a tax infringes on constitutionally guaranteed rights or applies selectively to an ethnic or religious minority, the court does not get to have a say.64

Article 26 (2) of the Fundamental Law also opened the way to reducing the retirement age for judges from 70 to 62,65 instantly removing the most senior 10 percent of the judiciary, including 20 percent of the Supreme Court judges and more than half of the presidents of all appeals courts. This action was declared illegal by both Hungary’s Constitutional Court66 and the EU’s Court of Justice,67 but by the time the judicial decisions were made, most of the judges had already left.

Fidesz also changed the electoral system to its own advantage. A two-round system for single-member constituencies was replaced by a first-past-the-post system assigning 106 seats and a nationwide proportional system responsible for distributing a further 93 seats on the basis of party lists. The reform thus strengthened the majoritarian element of the country’s electoral system, increasing the distance between the leading party—in this case, Fidesz—and its challengers.68 Moreover, reducing the number of seats entailed redrawing the electoral map—again, in a way that benefited the party.69 In 2014 and 2018, Fidesz won narrow two-thirds majorities in Parliament with less than 44 percent and 50 percent of the popular vote, respectively.

All printed daily newspapers in Hungary are either in the hands of Fidesz through proxies or subject to political control through government-sponsored advertisement. As in Russia, government sponsorship is a major source of revenue without which newspapers would go bankrupt. After the 2018 election, Magyar Nemzet, an independent right-wing newspaper, shut down. Its owner Lajos Simicska—initially a supporter of Fidesz who distanced himself from Orbán several years ago—divested himself of his media holdings, resulting in the further concentration of the few hitherto independent outlets in government-connected hands. These outlets include the broadcaster Hír TV, which followed a similar editorial line as Magyar Nemzet, and Heti Válasz, a weekly magazine that recently ceased its print publication.

In 2017, Hungary adopted new legislation on nongovernmental organizations.70 The law echoes Russia’s infamous law from 2012,71 which requires foreign-funded NGOs to register as foreign agents and be subjected to strict disclosing requirements. According to Fidesz’s Deputy Chairman Szilárd Németh, NGOs funded by George Soros “must be pushed back with all available tools, and I think they must be swept out.”72 The law was criticized by the Venice Commission, an advisory body to the Council of Europe, among others, as “[causing] a disproportionate and unnecessary interference with the freedoms of association and expression, the right to privacy, and the prohibition of discrimination, including due to the absence of comparable transparency obligations which apply to domestic financing of NGOs.”73

In Poland, as Agata Stremecka—president of the Warsaw-based Civil Development Forum—notes in her contribution to this report, the PiS government has built its popularity on virulently anti-elitist rhetoric combined with dramatic increases in social spending. These spending increases have provided a veil behind which PiS has started to tighten its control of government, starting with the judiciary. First, it made politically motivated changes to the composition and procedures of the Constitutional Tribunal. PiS responded to the contested election of five new Constitutional Court judges just before the parliamentary election in 2015. After the election, PiS and President Andrzej Duda sought to reverse the appointments, notwithstanding a ruling by the Constitutional Tribunal, which confirmed that the October election of 3 out of 5 judges was valid. Shortly before Christmas 2015, the Sejm, Poland’s lower house, passed an amendment to the existing law on the Constitutional Tribunal. The amendment would require a two-thirds majority instead of a simple majority and the presence of at least 13 of the 15 judges instead of nine for a decision as well as a mandatory latency period before it delivers a verdict on a case. The reform was declared unconstitutional by the Constitutional Tribunal operating under the old rules. For several weeks, the government refused to publish the decision in the Official Journal of Laws of the Republic of Poland.74

Furthermore, a sweeping overhaul of the judicial system gave the executive, specifically the minister of justice, unprecedented powers over judicial appointments, including at the level of presidents and vice presidents of ordinary courts. The reforms were criticized by the U.S. Department of State, which expressed concern over “[weakening of] the rule of law in Poland.”75 The most recent iteration of such judicial reforms was the lowering of the retirement age for Supreme Court justices from 70 years to 65 years, which resulted in the instant dismissal of 27 of the court’s 74 justices who would have had many years of service ahead of them according to the terms of their original appointments.76

Analysis: Populism and socialism: The case of Poland

By Agata Stremecka

New welfare programs and propaganda seem enough for the ruling party in Poland—the Law and Justice Party, or PiS—not only to win the October election but also to gain more supporters than they had in 2015 when they took power from Civic Platform after eight years of liberal governments under Donald Tusk’s premiership.

Other than fearmongering about immigration and slogans about restoring real national identity, the main items on PiS’ agenda in 2015 were social benefits. Under the 500+ program, parents receive tax-free 500 PLN, or about $130, per month for the second and any consecutive children until they reach the age of 18. PiS reversed the previous government’s pension reforms, which had increased the retirement age to 67. This year, a few months before the parliamentary elections, the Polish government went further: Benefits will also be given to first-born children until they reach the age of 18. This expansion of the universal program, which benefits the well-off as much as the poor, will cost the budget and all taxpayers around 41 billion PLN per year.

The polls from July 2019 show that PiS can count on the support of 42 percent of the electorate, compared with 22 percent going to the main opposition party. Opposition leaders have fallen into a trap of believing that, once extended, new social benefits cannot be taken away and they can promise to keep all the social programs if they win. Given PiS’ record, however, they will find it very hard to beat the incumbent party at its own game.

There is another distinction between the opposition and PiS. At a rhetorical level, PiS makes it clear that its enemy is the elite. In the party’s collective imagination, the elite encompasses the privileged, educated, arrogant, corrupt groups of people, including politicians. Feelings become so important for populists that they do not direct their program to individuals because it does not guarantee them the collective emotions they want to evoke. By appealing to the people, they build a sense of community and draw a distinctive identity. PiS consistently contrasts the real nation—which it claims to represent—with the elite of the Third Polish Republic. PiS claims that it is defending ordinary people—the so-called real Poles whose interests have been ignored by the treacherous elite.

In terms of populist policies, PiS has implemented most of its electoral promises. That was possible only thanks to a stable economic situation in the eurozone and domestic economic growth driven by exports. At the same time, the ruling party has subjugated the Polish court system, from the Constitutional Tribunal to the Supreme Court. In consequence, the justice minister has accumulated extraordinary power. Not only has he become the public prosecutor, but he has also gained significant influence over the common courts.

But PiS does not have a patent on populism in Poland. Political forces on both the left- and right-wing sides are susceptible to using propaganda, intimidation, and economic policies in order to gain political control. But as of now, not all leaders or parties that use populist language or political tools should be seen as equally dangerous.

The word “populism” is often a sign of intellectual laziness, especially when used to explain different types of illiberal trends. Trump’s, Orbán’s, Putin’s, and Kaczynski’s voters are different. While populist rhetoric might appeal to them, their backgrounds and motivations are different. That is why it is so difficult to look for just one, universal antidote to populism. But governments need to find solutions, before it is too late, in order to address the frustration of people who become both populism’s supporters and its unaware victims.

Agata Stremecka is the president of the Civil Development Forum, a Warsaw-based think tank.

These and similar attacks on the rule of law in central Europe have attracted the attention of European authorities, culminating in the triggering of the formal procedure under Article 7 of the Treaty on the European Union, which could result, at least in principle, in the suspension of voting rights in the European Council—an outcome that few observers expect to materialize.

Although populism and authoritarianism are connected, the connection is not an automatic one. The social democratic government of Romania—which would not qualify as populist in the same way as Fidesz and PiS—has attracted a similar degree of scrutiny from the European Commission as Poland and Hungary over its politicization of the judiciary, though ultimately falling short of triggering the Article 7 procedure.77 Conversely, the presence of populists in governments in other European governments—including Austria, Italy, and Finland—has not yet led to a visible deterioration of the quality of institutions. Even in Greece, where Syriza sought to exercise tighter control of the media market,78 concerns over an authoritarian drift seem to have eventually subsumed, particularly as Syriza reelection prospects have become weaker. In the Czech Republic, the ANO movement led by Prime Minister Andrej Babiš has strong Trumpist undertones, including its signature red hats. Yet ANO remains a member of the liberal ALDE group, and the government’s efforts to thwart an ongoing criminal investigation against Babiš have triggered a strong response from the opposition and civil society.

Populism’s impact on Europe’s trajectory

It is far from clear what the proliferation of populist governments, with their disparate governing strategies, and the fragmentation of Europe’s political systems mean for the EU and the trans-Atlantic alliance. In hindsight, the incessant predictions of the EU’s imminent collapse after 2008 have proven entirely wrong. Even after the Brexit vote, the EU has been far more resilient and durable than most of its critics and defenders imagined.

The Brexit referendum has deterred countries from following the United Kingdom’s example. The withdrawal negotiations demonstrated the EU’s ability to stay united in negotiations and adopt a firm line. The process has also shown how intertwined European economies are and how much upheaval would be caused by the United Kingdom’s disorderly departure. As a result, far-right populists have had to change course quickly. According to a 2016 report by the European Council on Foreign Relations, there were at least 15 political parties across Europe campaigning for a referendum at that time.79 As one of the co-authors of the report explains:

Today that message is practically nonexistent. Instead, in an ironic twist, nationalist parties are joining hands across the EU under Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini’s banner demanding a ‘Common-Sense Europe’: not the end of the European Union but a changed European Union, one that focusses more on security, manages immigration more closely, and takes a ‘nation first’ approach to the economy.80

The future of populist parties in Europe is also far from certain. One can imagine that if current, broadly benign economic and political trends continue, the appeal of populist parties will recede. It remains to be seen whether the upheaval in European politics was a passing phase fueled by the economic hardship of the Great Recession and a sudden spike in migration or if it is indicative of a permanent shift. In either case, however, Europe is at risk if the current economic and political trend lines change. The continent’s resilience has been greatly depleted since the 2008 financial crisis. With more unstable and fragmented politics, the EU would be in an even more difficult position to deal with another economic recession or a political crisis.

European politics has also become more adversarial, coming to increasingly resemble hyperpartisan politics in the United States. This is in stark contrast to the normally staid consensus-based politics associated with countries such as Sweden. These sharper partisan cleavages could limit the EU’s ability to pursue political and economic reforms that could help strengthen its resilience in a future crisis.

While political momentum in Europe seems to be behind the political parties and leaders that advocate for change, implementing that change for pro-European parties could prove difficult. In a bitterly divided Europe, efforts to make Europe more economically resilient in the event of another financial crisis; foster greater economic growth; strengthen the EU’s role in defense; or address issues such as migration in a European context are difficult to push through. The reason is not simply the opposition of far-right parties but also the caution of many centrist parties such as the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) of Germany. For example, French President Macron has sought to push reform initiatives for the European Central Bank, a eurozone budget, and European defense.81 These proposals have gained no support from German Chancellor Angela Merkel and her CDU party, resulting in a stinging political setback for Macron and others who campaigned on strengthening the EU. The new divisive environment could make it more difficult for pro-EU leaders to deliver on their promises, which could not just disappoint their voters but also make pro-EU parties seem ineffectual.

Another complicating factor for advocates of the EU’s deeper integration is that past reforms largely have taken place out of the public spotlight. There are many reasons for the EU’s famous democratic deficit, but perhaps the main reason for the absence of genuine deliberation over key policy decisions in the EU was the shared consensus between center-right and center-left political parties in support of deeper European integration. Now that European integration is the focus of a major pancontinental debate, far-reaching reforms are unlikely to simply skate through in the future. This is likely a necessary attribute of a more aware and engaged European polity. At the same time, it also makes reaching a general consensus among European states a huge challenge, as reactionary politics in at least a few EU member states at any given time will spur significant backlash.

A major area of concern that makes the EU vulnerable to economic shocks is the divergence in economic performance and debt levels in the eurozone. The lack of a common fiscal architecture and comparable levels of economic competitiveness, paired with the political difficulty of implementing future reforms in the divided European political environment, means that the EU will confront any new economic crisis with a similar toolbox as it did in 2008. This toolbox consists of a fiscal stabilization plan prescribed by the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the IMF; ad-hoc financial support from the European Stability Mechanism; and a dose of economic stimulus from the European Central Bank. Such an approach may prove inadequate for economies such as Italy’s, which has had essentially no economic growth in the two decades since the adoption of the euro.

Another economic downturn on the eurozone’s periphery would bolster far-right populists who would blame the EU, not without some merit, for contributing to the economic downturn, especially by constraining the ability of nation-states to respond. The EU could serve as an easy and convenient scapegoat for the political forces that have already been emboldened since the last crisis.

A populist international

The resurgence of Europe’s far-right has led to efforts to create a cross-European nationalist movement—a “nationalist international” of sorts. Steve Bannon moved to Italy to help build such a movement. Thus far, his efforts have largely amounted to self-aggrandizing bluster. In the European election, the far-right did not exceed their performance in previous national elections,82 and Bannon’s haphazard efforts generated little political energy.83

In light of the far-right’s disparate governing strategies and oftentimes conflicting goals, their limited ability to form a pan-European force is not surprising. However, rather than transforming the EU, the anti-European forces are more likely to effectively block any action at the EU level and thus paralyze the bloc, especially in times of crises. According to a recent announcement by 73 members of the European Parliament, led by Le Pen’s National Rally, Salvini’s League, and Germany’s AfD, the far-right will push to return power back to the states and curb immigration instead of helping to create a common system of asylum policy that is needed to sustain the Schengen Area—the EU’s area of passport-less travel.84 Blocking reform and scapegoating Brussels is far easier than proposing, rallying support for, and successfully implementing necessary reforms. By hindering the EU’s ability to respond and function, populists are effectively sowing the seeds of their own political growth.

While a common legislative agenda is unlikely, members of the nationalist international can learn from and emulate each other, pushing the boundaries of what is acceptable within the EU. Orbán’s authoritarianism, for example, has provided a model for Poland’s populist government to emulate. Similarly, populists are likely to emulate the so-called tough approaches of Orbán or Salvini in dealing with migrants and asylum-seekers—or even those implemented by the Trump administration. Populists could also disregard the common fiscal rules in the eurozone, pushing the monetary union on an unsustainable trajectory and undermining the authority of European institutions and the EU’s shared norms and values.

The looming risk is no longer the EU’s unraveling but rather its hollowing out in a number of policy areas, including the common market. Populist governments are already seeking to reassert their authority over national economies, leading to standoffs with EU institutions. Those standoffs often work to the populists’ domestic political advantage, as populist leaders pick fights with the EU on issues on which they enjoy substantial domestic support. Following the European election, for example, Italy’s Salvini claimed a mandate to change EU budget rules and rekindle a showdown with the European Commission.85 The EU might easily become overwhelmed by such attempts to reopen a variety of rules and policies, especially if political leaders see standing up to Brussels as a winning political strategy.

The EU might therefore find itself in an unstable position. Far-reaching reforms to the EU that are needed to bolster resilience and address common challenges are likely to be blocked. At the same time, the far-right will tend to avoid outlandishly extreme efforts such as leaving the EU altogether. Instead, populists likely will seek to exert more national control in ways that could gradually undermine the European project. The populist threat to the EU may come in the form of a death by a thousand cuts rather than a single existential confrontation.

Instability ahead in trans-Atlantic relations

With the rise of China, the resurgence of Russia, and the revival of an ideological challenge to liberal democracy in the form of strongman authoritarianism, the trans-Atlantic alliance is once again critical to the security of both the United States and Europe. Europe’s likely instability and the erratic nature of the current administration in Washington pose distinct challenges to the future of the alliance.

President Trump’s disdain for the alliance, reluctance to commit the United States to upholding its commitment to Article 5—”an attack on one is an attack on all”—and his treatment of the alliance as a protection racket has severely shaken the alliance.86 So far, President Trump’s hostility toward NATO has not permeated his administration—in particular, the U.S. military and Congress. The United States has continued to fund a significant expansion of U.S. force presence in Europe, especially in Eastern Europe. However, the Obama administration’s European Reassurance Initiative has become the European Deterrence Initiative during the Trump administration.87

Like the EU, the trans-Atlantic alliance has proven resilient, despite the consternation over President Trump’s outbursts on social media.88 In one sense, the president has opened a conversation that will not go away easily, no matter how much the political landscape changes on either side of the Atlantic. Europe’s lack of defense spending is a real issue of concern to the United States. While there have been marginal increases in defense spending, political incentives for European politicians are stacked firmly against defense spending increases in part because of Trump’s own unpopularity among Europeans. For instance, the Social Democratic Party in Germany has opposed efforts to increase defense spending, enabling it to highlight a difference with the CDU.

However, the decline in European defense spending also reflects a shift on the continent over the past 20 years. With the role of the nation-state shrinking within the EU, so has the importance to European public officials of maintaining a capable national military force. European citizens no longer draw national pride from the military strength of their nation, as they have done historically. The decrepit state of the German military, despite Germany’s economic stature, is the most striking example. However, reframing defense as a common European challenge creates a deep collective action problem, making spending increases even more costly in political terms.

The rise of Europe’s far-right may worsen the trans-Atlantic discord over defense spending. Since defense spending is largely treated as part of a collective duty or responsibility to contribute to the NATO alliance or European security, rather than the defense of the nation, populist leaders may chafe at calls for more spending that would take away from domestic priorities. Indeed, France’s Le Pen has supported pulling back from NATO.89 Furthermore, the affinity of some populists with autocratic states, such as China and Russia, will likely also mitigate their willingness to devote resources to collective defense efforts that are designed to counter these countries.

Another challenge to the trans-Atlantic alliance is the Trump administration’s outright ideological hostility toward the EU and its zero-sum view of international trade. The Trump administration has threatened to impose tariffs on imports of European cars, ostensibly on national security grounds. Ironically, populist governments would be among the biggest losers of such move since Audi and Mercedes count among the largest employers in Hungary. Such tariffs would inevitably provoke a retaliation from the EU, sending trans-Atlantic relations in a downward spiral.

Furthermore, the Trump administration has adopted a hostile approach toward the EU, extending beyond President Trump’s cheering for a “no-deal” Brexit. In his speech in Brussels last year, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo asked bluntly whether the EU “is ensuring that the interests of countries and their citizens are placed before those of bureaucrats here in Brussels?”90 The Trump administration temporarily downgraded the EU’s diplomatic status in Washington and has met the EU’s limited common defense initiatives—the European Defence Fund and Permanent Structured Cooperation—with hostility. As a result, European leaders often try to avoid interacting with the White House in order to avoid worsening diplomatic relations.

Although President Trump is in many respects an aberration, the fundamentals of the current situation will likely persist even if he is not reelected in 2020. Even if there is a new administration in Washington, efforts to strengthen trans-Atlantic relations and forge common trans-Atlantic approaches toward issues such as climate change, trade, Russia, and China will likely find themselves having to work around European populists. While European populists are not uniformly opposed to NATO or trans-Atlantic relations, they likely will not be enthusiastic partners on key issues—such as countering Russia or China or addressing global problems—with a possible new Democratic administration. Therefore, should the far-right take the reins of government in one or several prominent European countries, the trans-Atlantic alliance would likely find itself in a very similar position to where it finds itself today—keeping its head down and trying to maintain its military posture while avoiding high-profile political fights.

Conclusion

Populist parties are destabilizing European politics. The rise of populist parties, particularly on the far-right, and the fragmenting of European politics complicates the formation of governing coalitions.

Europe’s politics are taking on an increasingly divisive character, more resembling the deep partisan divides of the United States than the consensus-oriented politics that characterized postwar European democracies. The divide between urban cosmopolitan cities linked to the global economy and more rural and postindustrial regions overwhelmed by massive economic and cultural change has fostered a sharper, more intense ideological debate. This divide has often manifested in fierce divisions over immigration, globalization, and the European project, many of which were on display in the campaigns prior to this year’s European election.

This divide has prompted passionate debates over the future of Europe. The increasing political fragmentation and polarization make any single path forward—including the five scenarios outlined in the European Commission’s 2017 white paper91, “carrying on,” “nothing but the Single Market,” “those who want more do more,” “doing less more efficiently,” or “doing much more together”—contestable and potentially unstable. Deeply held views on the EU mean that new initiatives will be blocked and reversed, likely leading to stagnation and the preservation of the status quo. If confronted with another crisis that requires a concerted response, the EU may not be able to rise to the challenge. Populist political parties that thrive on scapegoating the EU may block needed action, all while positioning themselves to use the crisis to their political advantage.

Almost by definition, nationalists lack a transnational governing agenda. Yet by indiscriminately challenging the status quo, undermining long-standing norms, and charting new paths that other populist leaders can emulate, populist forces have contributed to a more unpredictable politics across Europe. Policy paralysis, the hollowing out of the EU, and inability of the EU to exert its authority over recalcitrant members represent the biggest challenges to the bloc—not necessarily the risk of its sudden collapse.

The turmoil in European politics will pose a considerable challenge for the trans-Atlantic alliance. While all eyes are on the current occupant of the White House and his disdain for NATO and the alliance, Europe’s fragmented and adversarial politics are likely to present similar challenges in the future. This may prevent the alliance from working together to contain rising autocratic powers and address challenges to the international order. The possibility of such an outcome—an ineffectual and divided alliance—is arguably the greatest geopolitical threat confronting the current generation of trans-Atlantic political leaders.

About the authors

Matt Browne is a senior fellow at American Progress and director of Global Progress, where he works on building trans-Atlantic and global progressive networks. He also leads American Progress’ work on populism. Previously, Browne was director of Policy Network—the international network founded by Tony Blair, Gerhard Schröder, Goran Persson, and Giuliano Amato. He remains a member of the organization’s governing board and advisory council and also serves on the boards of Canada 2020 in Ottawa, Volta Italia in Rome, Tera Nova in Paris, and Progressive Centre UK in London. Over the past two decades, Browne has worked closely with a host of progressive leaders, prime ministers, and presidents across the globe, as well as with international organizations such as the United Nations, European Union, and the World Trade Organization.