June 12 was supposed to be the end of the road for colleges that relied on the Accrediting Council for Independent Schools and Colleges (ACICS) for access to federal financial aid, marking 18 months since the U.S. Department of Education stripped the problematic accreditation agency of its ability to serve as gatekeeper to federal student aid. The date would also have ended the mandated transition period after which ACICS schools that had not obtained accreditation elsewhere would no longer be able to receive student grants and loans. ACICS colleges received an unexpected reprieve this April, however, when Education Secretary Betsy DeVos decided to temporarily reinstate ACICS and eliminate the June 12 deadline.

According to a new data review,* the restoration of ACICS was a windfall for most of the 85 colleges that failed to find a new accrediting agency by June 12. The majority of these colleges failed to demonstrate that they were able to meet any other agency’s quality standards and would have lost access to taxpayer money had the deadline remained in place.

What happens next to most of these colleges is unclear and tied to ACICS’ future. The Department of Education is currently reviewing additional materials that ACICS submitted on May 30, and a Trump official will issue a recommendation to the secretary about the agency’s future by the end of July. In April, 10 Senate Democrats raised concerns that the deciding official would be Diane Auer Jones—a former for-profit college lobbyist and consultant for corporations that once owned ACICS-accredited campuses. If the department elects to terminate the agency’s recognition again, then schools could have another 18 months to find a new accreditor. Alternatively, the department could choose to approve ACICS for up to five years, temporarily putting those schools out of danger.

It’s uncertain how the department’s leadership will view ACICS, but career staff are wary of the agency’s ability to meet federal standards. Though a recent report from the department’s career staff found the agency out of compliance with 57 of 93 criteria required for federal recognition, their findings will not be considered in Secretary DeVos’ review. ACICS responded to the draft report with claims that it included numerous inaccuracies and submitted information to correct the record and demonstrate its compliance. In the meantime, ACICS—an agency known for its lax gatekeeping—is overseeing colleges that were unable to find a new accreditor by the deadline.

85 colleges failed to find new accreditation

Based on an analysis of public documents as well as accreditor and institutional websites, since the December 2016 decision to strip ACICS of its federal recognition, 85 colleges failed to find approval elsewhere, 61 colleges closed, and 111 colleges gained accreditation with a different agency by the June 12 deadline. For the 85 colleges that would have lost access to federal student aid—which accounts for the majority of their revenue—this likely would have led to their closures. These schools received a combined $772 million in taxpayer-funded federal student aid and had an unduplicated 12-month enrollment of slightly less than 111,000 students in the 2016-17 academic year. While this tally isn’t insignificant, it is drastically lower than funding and enrollment levels from where the agency was at its height. In June 2016, ACICS colleges received almost $5 billion in federal student aid and enrolled more than 361,000 students.

Seventy-two of these 85 colleges—comprising 78 percent of enrollment at these schools—made it to the final review step at a new accreditor but have not yet received approval. The largest group of these colleges—accounting for 45 percent of enrollment—belongs to Education Corporation of America, which operates Brightwood College, Virginia College, and Professional Golfers Career College. After the Accrediting Council for Continuing Education and Training (ACCET) denied accreditation from Virginia College last month, it issued a long letter detailing the school’s systemic failures—including that 31 of its 33 campuses failed to meet minimum graduation and job placement standards and that some campuses had significant employee turnover rates, including one as high as 75 percent. In response, ECA stated that the review covered less than half of its campuses and that it had only two weeks to respond to the reports, some of which they claim contain errors. Virginia College is appealing the decision. While the agency has not outright rejected Brightwood College campuses, they’ve been continuously deferred and will be reconsidered in December.

Also notable among the 85 are two branches of the Art Institutes that tried to become branches of Art Institute locations currently accredited by the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools (MSCHE). The move was caught up in a larger decision on a change of ownership and conversion from a for-profit to nonprofit college. The Art Institutes’ parent company, Education Management Corporation (EDMC), sold the campuses to the Dream Center Foundation, a company with no experience in higher education. The Dream Center just announced yesterday that it would close 30 campuses, including the two owned by ACICS and one owned by MSCHE. The MSCHE campuses’ accreditation statuses were already in jeopardy, as they remained sanctioned over concerns including whether the campuses are financially viable over the long-term.

Another ACICS college that failed to find approval elsewhere, Florida Technical College, reached a $600,000 settlement with the Department of Justice earlier this year over allegations that the school received financial aid for ineligible students. The college allegedly submitted falsified high school diplomas for 27 students, resulting in more taxpayer money flowing to the school at the expense of students who took on debt. The school denied any wrongdoing in the settlement.

Currently, at least 5 of the 99 colleges that failed to find a new agency by the deadline appear to be unaccredited, although their accreditation status is unclear. Key College, PPG Technical College, Global Health College, and Colegio Tecnologico y Comercial de Puerto Rico all voluntarily withdrew accreditation with ACICS; Northwest Suburban College had its accreditation withdrawn.

Where the campuses have gone

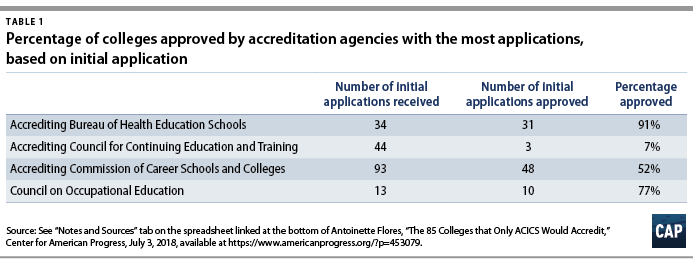

Among accreditors that received the largest number of applications from ACICS schools, the Accrediting Bureau of Health Education Schools has approved the highest percentage of colleges—accrediting 31 of the 34 colleges that submitted an initial application. The Council on Occupational Education had the next-highest approval rate at 77 percent, though it received just 13 applications. The Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges (ACCSC) has approved the highest number of colleges at 48, but has done so at a lower percentage of about 52 percent due to the high volume of initial applications. ACCSC now replaces ACICS as the largest national accrediting agency. ACCET approved the smallest percentage of schools, granting accreditation to only 3 of the 44 that initially applied.

In June 2017, CAP questioned whether ACCET was equipped to handle such a large number of applicants, but the results here are encouraging and show that the agency has taken a rigorous approach to its decisions. While ACCET’s president has publicly advocated to extend the June 12 deadline to give colleges “who have done everything properly” more time to come into compliance, the agency has also made clear that it took seriously the issue of unacceptable job placement and graduation rates in its decisions and its rejection of Virginia College.

What’s next for ACICS and its schools

Now that the June 12 deadline has come and gone, what happens to ACICS and the colleges it oversees is unclear. ACICS colleges’ futures all depend on the decision currently making its way through the department. Even if the agency is found to be out of compliance, it still may get another 12 months to come into compliance. The remaining ACICS schools are safe for now, but given evidence that none passed other agencies’ bars by the deadline, their situations remain precarious. In the meantime, the futures of the thousands of students continuing to enroll in colleges of questionable quality are at risk.

Antoinette Flores is an associate director for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress.

*Author’s note: These data are based on U.S. Department of Education databases and FOIA requests and are available here.