This column was originally published on MarketWatch.

It is safe to say that the U.S. labor market is now out of jobless-recovery territory and into the territory of wageless recovery.

Employers added 252,000 jobs in December 2014, and the unemployment rate fell to 5.6 percent, according to new data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, or BLS. Since the start of the labor-market expansion in February 2010, private employers have added 11.2 million new jobs.

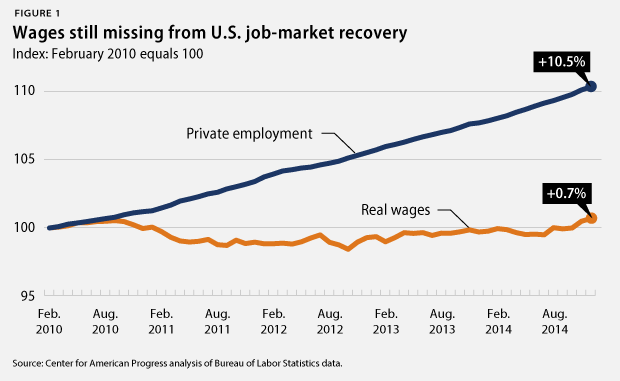

But while jobs are becoming more plentiful, wages are not. Private-sector jobs have rebounded by 10.5 percent since the labor market exited the Great Recession in February 2010. But average wages, adjusted for inflation, have grown merely 0.7 percent over the past five years. And most of this wage growth has occurred in just the past few months, with lower global oil prices leaving a little more spending money in U.S. workers’ pockets.

Having oil drop to $50 per barrel certainly helps businesses’ and households’ budgets. But cheap oil is not a trend that people should bank on continuing, nor is it enough to ease the severe financial squeeze that most families feel while trying to pay for the essentials of a middle-class life: higher education; housing, especially for renters; child care; and saving for retirement. Which brings us to the questions of why wages are not growing for the vast majority of workers in the United States and what it will take to get us there.

First, the trend of stagnating U.S. wage growth is nothing new. The past three decades of wage growth—save for the late-1990s boom—have given the median U.S. wage earner little to crow about. The same factors that have been dampening wages for 30 years are still in force now, if not more so than before: globalization and technological changes in how we work and organize businesses, combined with the loss of worker bargaining power reflected in declining unionization and an erosion of the real value of the minimum wage.

The U.S. economy is not suffering for want of producing income: Gross domestic product, or GDP, grew an average of 4.8 percent in the second and third quarters of 2014, according to separate data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s “GDPNow-cast” estimates that GDP grew by 3.3 percent in the fourth quarter of 2014. Worker productivity is up in the nonfarm business sector, and overall income is surging. But the distributional bargain between bosses and wage earners in America still holds, with the top percentile still taking home the majority of the gains.

Second, we tend to only see wage gains broadly across U.S. workers when the economy approaches full employment. Despite the unemployment rate falling to 5.6 percent—a level consistent with the Federal Reserve’s view of full employment—the new BLS report shows symptoms of ongoing and elevated disguised unemployment, meaning people who are unemployed but not counted because of how the official statistics are defined. Broader indicators of unemployment stood at 11.2 percent of the workforce, or 17.5 million people, in December. These broader indicators include those marginally attached to the labor force—people still looking for work, just less recently—and those working part time because they cannot find full-time work.

Still more people have left the labor force altogether, discouraged with the prospects for employment: Only 63 percent of the U.S. population was active in the labor force in December 2014, compared with 65 percent in February 2010 and a recent high of more than 66 percent in January 2007, according to BLS data. Demographics are shifting in the United States, and an aging population will shrink the active labor force. But this aging population is not yet to blame for the current decrease in the labor force. What is happening, rather, is that some populations that left the labor force still exhibit reluctance to jump back into it. December’s employment report shows that the number of people re-entering the labor force slowed by 60,000 people, and the number of people newly entering decreased by 74,000 over the prior month; the number of people voluntarily leaving jobs also fell by 37,000.

These potential workers’ assessments of job-market conditions are also mirrored by employers’ seemingly low demand for labor. Employers typically expand work hours before hiring permanent new staff, but at present, employers seem content to meet the demand for the current levels of work they need. Average weekly work hours and overtime hours remained essentially unchanged over the past 12 months, with the construction industry registering a notable exception, giving no indicator of accelerated future hiring.

Third, where the job growth is occurring matters a lot: Job growth has mostly been concentrated in low-wage occupations, in jobs that often have nontraditional work schedules, and in fields that offer fewer opportunities for career advancement. Taken together, new jobs in the retail trade industry, leisure and hospitality industries, temporary employment services, and home health care services account for nearly 40 percent of the total job gains in the private sector.

The magic of the market alone will not guarantee adequate job and wage gains in the economy. Fortunately, we do not need magic to get people back to productive work and raise wages—there are simple, common-sense steps that the new Republican-led Congress could take today, if it were so inclined. Two no-brainers to start with: expanding investment in infrastructure and science to raise demand today and expand our economy’s supply side for stronger long-term growth and raising the minimum wage so that hard workers earn their fair share.

Adam S. Hersh is a Senior Economist at the Center for American Progress.