Israel held early general elections on March 17, 2015, following the collapse of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s coalition government. Many found the election results surprising because pre-election polls predicted victory for the main opposition list, the Zionist Union, and a possibility that the center-left bloc might compose the next government. In the end, however, the election did not mark a real transformation in the relative power of Israel’s political blocs, and Netanyahu’s Likud Party won more seats and is likely to establish the next government with its coalition partners.

The next coalition government will likely be based on a narrow coalition between right-wing and religious parties. Although the new government will be more ideologically coherent than its predecessor, the basic rifts in Israeli society will endure—including the fragmentation and dysfunction of the political system. These rifts will continue to pose a serious threat to the longevity of the new government.

Glossary

List: In the Israeli elections system, the voters vote for lists of candidates. Most lists represent parties, but some represent a union of two or more parties in one list for the sake of the elections. In these elections, the Zionist Union was a combined list of Labor Party Chairman Isaac Herzog’s party and former Israeli Justice Minister Tzipi Livni’s party. The joint list consisted of three different Arab-Israeli parties.

Right-wing bloc: Likud, The Jewish Home, and Yisrael Beiteinu

Center-left bloc: Zionist Union, Yesh Atid, Kulanu, and Meretz

Ultra-Orthodox bloc: Shas and United Torah Judaism

Arab bloc: Joint List

Election results

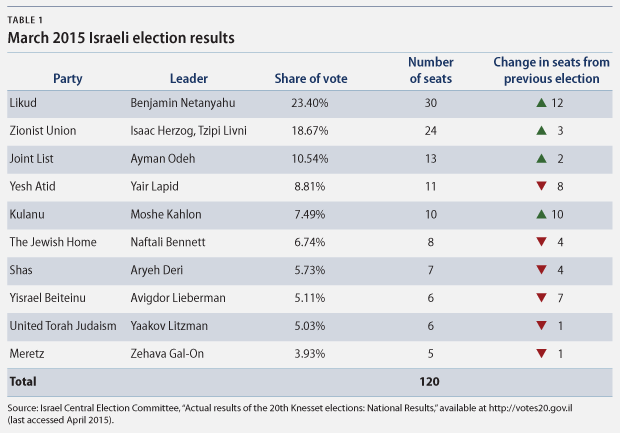

Israel’s election results surprised many. Pre-election polls in the weeks before the elections indicated that the main opposition list, the Zionist Union, would win the most seats in Israel’s parliament, the Knesset. The actual results of the elections gave Netanyahu’s party a victory: Likud won 30 seats, and the Zionist Union won 24. (see Table 1)

Despite its victory, Likud only won one-quarter of the seats in the Knesset and therefore must establish a coalition government with other parties. In theory, any party that can put together a majority coalition of more than 61 Knesset members can form a government. But the gap in the number of seats between the two biggest lists makes this outcome unlikely. Therefore, the showing of ideologically similar political blocs becomes critical. Here, the results undercut the narrative of right-wing triumph. The right-wing bloc—including Netanyahu’s Likud, as well as The Jewish Home and Yisrael Beiteinu—won a total of 44 seats, three less than in the previous Knesset. In contrast, the center-left bloc—from the centrist Kulanu party to Meretz on the left—won 50 seats, two more than in the last Knesset. Ultra-Orthodox religious parties won 13 seats, five less than in the last election, and the Arab bloc won 13, two more than in the previous election.

Enduring, deep divisions in Israel’s political landscape

The elections had a greater impact within Israel’s political blocs than on the balance of power between them. Netanyahu cannibalized other right-wing parties by convincing their voters that only Likud could successfully lead the right-wing bloc to a government. This strategy worked, and Likud picked up 12 seats, while the parties of his right-wing rivals Avigdor Lieberman and Naftali Bennett lost a combined 11 seats. Similarly, Herzog’s center-left Zionist Union list took votes away from Yair Lapid’s centrist Yesh Atid and the left-wing Meretz.

Internal fragmentation did lead to minor changes in the overall size of the right-wing, center-left, and ultra-Orthodox blocs. For example, the ultra-Orthodox and right-wing blocs lost seats when Shas split. One of the resulting splinter parties united with a right-wing faction; together, they failed to clear the 3.25 percent vote threshold for entering the Knesset.

The only real change in the Israeli political landscape was the growth of the Arab bloc, which benefited from increased Israeli Arab voting rates. These rose from 56 percent in the previous elections to 63.5 percent in this election. In response to increases in the threshold for entering the Knesset, Arab parties were forced to unite in one list. This move mobilized Israeli Arab voters who were previously alienated by internal bickering among the Arab parties. It is unclear, however, whether this bump in Israeli Arab political participation can survive the disappointment of Prime Minister Netanyahu’s perceived victory.

The road ahead for government formation and beyond

According to Israeli law, the president of the state nominates one of the members of the newly elected Knesset—on the basis of the recommendation from the parties that have seats in the new Knesset—to compose the coalition government. The member has four weeks, with a possibility of a two-week extension, to compose a government that has the support of the majority of Knesset members. This time is needed to agree on the division of ministries between the coalition partner parties and the agenda of the new government, as well as on the procedures of decision making in the government.

Potential coalition led by Isaac Herzog

In theory, Zionist Union leader Herzog could form a coalition of the center-left bloc, the Arab bloc, and some ultra-Orthodox parties whose leaders take moderate positions on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In practice, however, such a coalition is impossible for three main reasons:

-

The relatively large difference in the number of seats won by Likud and the Zionist Union. This difference created the perception of a Netanyahu victory. Under these circumstances, it is likely impossible for parties that also court right-wing voters—such as Kulanu and the ultra-Orthodox parties—to support a Herzog government.

-

Most parties are not single issue. Many have mutually exclusive goals that would preclude participation in the same government. Yesh Atid, for example, would likely find it extremely difficult to join a coalition with the ultra-Orthodox parties.

-

Most Zionist parties remain ideologically and politically committed to forming coalitions that enjoy the support of a Jewish majority. This includes all of the Jewish parties—with the exception of Meretz, which does not define itself as a Jewish party. Because a likely Herzog coalition would include Arab parties, the coalition might not enjoy the support of a Jewish majority. This commitment will persist at least as long as relations between Israel and the Palestinians remain a central issue for any Israeli government.

Consequently, nobody was surprised when President Reuven Rivlin asked Netanyahu on March 25, 2015, to try to compose a coalition government.

Potential coalition led by Prime Minister Netanyahu

The more likely scenario is that Netanyahu will form the government, and he has a choice between two different types of coalitions:

-

A narrow coalition between right-wing and religious parties

-

A wider national unity government that, at a minimum, includes the Zionist Union

Netanyahu has been resistant to a coalition with the Zionist Union. Rumors that Netanyahu will invite Herzog to join his government are more likely a symptom of political jockeying than a signal of serious intent.

Assuming that the new Netanyahu government will be based on a narrow coalition made up of right-wing and religious parties, this government would enjoy greater internal cohesion than Netanyahu’s previous government. But it could also alienate almost half of Israeli society—Israel’s center left and Israeli Arabs. The more extreme elements of a right-wing government would likely advocate hard-line policies, including: an expansion of settlements; greater Israeli control over the Temple Mount; and more limitations on Palestinians in the West Bank, tougher responses to attacks from the Gaza Strip and legislative limitations on human rights. Such moves also would likely deepen rifts with Israel’s major international allies: the United States and the European Union. Additionally, it may spark greater criticism of Israel in the West and accelerate the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions, or BDS, movement.

Netanyahu has faced this dilemma before and has demonstrated that he is acutely sensitive to these competing pressures. The result could well be a government that is even more limited in executing right-wing policies than his last government because its actions will be observed more closely and critically by the significant international actors. This dynamic would make it easier for the United States and the European Union to demand action to improve the situation of the Palestinians and to limit the expansion of settlements. Netanyahu has already taken steps in this direction by releasing tax money to the Palestinian Authority and preventing new building in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Har Homa. Such moves will likely create strong tensions within a right-wing coalition government. Netanyahu would then be forced to maneuver between external and domestic pressures and internal coalition tensions. The result would be a government that, similar to a tango, takes one step forward while taking two steps back.

The new Netanyahu government would not preclude a new round of talks with the Palestinians, assuming—and this is a big assumption—that the Palestinians are willing to drop some of their publicly stated conditions for returning to the table. On the other hand, if the Palestinians continue to challenge Israel in the international arena through the International Criminal Court, or ICC; the U.N. Security Council; and other international forums, Netanyahu will likely feel obligated to punish the Palestinian Authority. But even if negotiations resume, it is hard to envision the scenario under which a new right-wing government concludes a full agreement with the Palestinians. Interim measures would therefore be needed to reduce Israeli-Palestinian tensions and keep the political space open for future rounds of negotiations. These steps may include limited agreements on specific issues and coordinated unilateral moves.

Prime Minister Netanyahu probably perceives his electoral victory as a demonstration of the Israeli public’s support for his Iran policies, including his controversial steps vis-à-vis the United States. He will therefore feel no need to change his basic agenda and policies on this issue. However, Netanyahu probably understands that some of his actions—for example, his speech to the U.S. Congress in March—created some negative blowback when it comes to Iran. Any future attempt by Netanyahu to voice concerns, legitimate or otherwise, over the terms of an Iran deal may be seen by the Obama administration as an attempt to undermine negotiations. His actions before the elections created further distrust among the Obama administration and many Democrats, and Netanyahu should look for ways to rebuild trust and relations with the Obama administration if he wants to have an impact on the outcome of the Iran negotiations.

In the Israeli domestic arena, matters of foreign policy may contribute to growing tensions between the right-wing and religious sectors of the population on one side and the center-left and Arab sectors on the other side. However, domestic tensions will probably focus more on issues such as economic inequality, human rights, and the role of religion in the state. The new government will probably focus on the economic issues, trying to bring down the cost of living as a way of reducing domestic pressures. Past experience, however, shows that there are many limits to what the government can do in this area without deviating from the free-market principles to which the Likud and other parties in the coming government strongly adhere. There will also likely be constant tension between the right-wing nationalistic government’s need to keep a very high defense budget and its need to supply good services at a reasonable cost for the people. Tensions within the coalition may eventually shorten the term of the new government—a common phenomenon over the past two decades—and Israel will likely be forced again to go to early elections.

Recommendations and conclusion

The Obama administration has consistently declared that it will work with every elected government in Israel. The current administration might feel that the composition of the Knesset will make it difficult for the two governments to work together, but it is in the interest of all involved to continue this dialogue. Consequently, the administration should identify who will be the best contacts in the new Israeli government for this partnership. In spite of political and ideological differences, the problems of the Middle East will give the two sides ample reasons to coordinate their policies.

The tensions created by the expected establishment of a narrow coalition government in Israel will make the government more susceptible to external pressures and therefore may also produce opportunities for the United States to affect the policies of the new government, preventing a complete stalemate in the Israeli-Palestinian relationship and repairing damage to the U.S.-Israel relationship. Without repair, the strain on the U.S.-Israel relationship could have long-term strategic consequences during a period when stability is a rare commodity in the Middle East. Accordingly, the Obama administration should develop an understanding of what such a coalition in Israel is and is not capable of digesting.

The United States should follow closely the development of the Israeli-Palestinian relations to determine if and when it might be possible to resume Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. Even then it should consider whether it makes sense to resume formal negotiations on a full agreement when the odds of success are so small. Another failure could be detrimental to the future of Israeli-Palestinian relations. More realistically, a package of more limited and partial mutual steps may be a more effective way of stabilizing the Israeli-Palestinian relationship without taking too many risks.

Additionally, it is likely that negotiations with Iran will continue to create more stormy controversies between the Obama administration and the Netanyahu government, at least until the negotiations that are scheduled to conclude on June 30 end—either with an agreement or a failure. Nevertheless, both sides should make special efforts to prevent Iran from becoming a partisan issue in the United States and further harming important strategic ties that are beneficial for both Israel and the United States in a chaotic and uncertain Middle East. No matter which of these two scenarios unfolds—a conclusion of a final deal or a failure of the negotiations—the United States should work closely with Israel after June 30 to deal with the consequences.

If the built-in tensions of a narrow coalition government in Israel shorten its life span and bring about a new round of early elections, it would create another opportunity for Israel’s liberal opposition. But the opposition must first use its time wisely, reorganizing, asserting a clear identity that is distinct from the ruling government, and proposing a viable alternative. This could include an effort to mend the relationship with Israel’s Arab citizens—who are suspicious of all Zionist parties and feel specifically betrayed by the center-left parties, which have alienated them in spite of their general liberal positions. Such an effort would remove an almost automatic electoral advantage for the right-wing bloc.

The result of the 2015 Israeli general election will likely bring about the establishment of a narrow right-wing government, further complicating the relations between the United States and Israel. However, it will also bring more clarity to these relations, and the United States will still be able to prevent Israel from implementing extreme right-wing policies, thus enabling the two countries to continue necessary cooperation on issues that are vital for the stability of the Middle East.

Shlomo Brom is a Visiting Fellow with the National Security and International Policy team at the Center for American Progress and previously served as brigadier general in the Israel Defense Forces.