From the lobstermen of Florida to crabbers in Alaska, fishing communities depend on their local marine ecosystems. However, because climate change is not uniform or linear, the continued release of anthropogenic carbon will affect each local region differently. This report shares some of the localized effects of global climate change that American fisheries experience today.

Florida

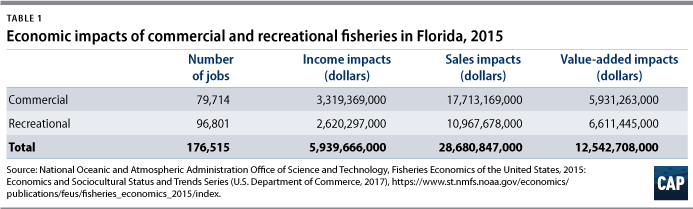

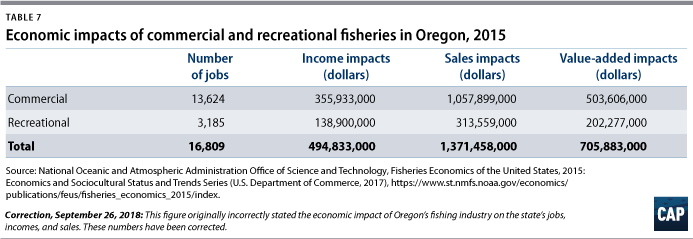

With 1,350 miles of saltwater coastline, commercial and recreational marine fishing is a big business in Florida.35 In 2015, Florida’s commercial and recreational marine fishing industry supported 176,000 jobs and generated $28.7 billion dollars in sales, ranking as the third-highest state in employment impacts and second-highest state in sales, income, and value-added impacts. Florida leads the nation in recreational angler trips, recreational fishing jobs, and local taxes generated by sportfishing.36 In saltwater-fishing license fees alone, Florida generates $26.8 million dollars, 46 percent of which come from out-of-state fishermen.37 Yet, warming waters and more frequent extreme weather events are already damaging the Florida fish stocks that support this key economic sector.

Nationally, fish stocks are managed on a regional basis, with quotas set by regional fishery management councils and state agencies based on historical catches and regular scientific assessments of the number of adult and juvenile fish present. As ocean temperatures skyrocket, heat-sensitive fish and other marine life are moving to more comfortable waters. By moving away from the habitats and fishing grounds on which those historical records are based,38 climate change is causing a mismatch between where fish actually are and where they are allowed to be caught, leading to severe economic hardship for fishermen and the businesses and communities they support.

“Cobia are very much a migratory fish, and their migratory patterns from Texas and Florida are both about six weeks off,” said Brandon Shuler, a professor at the University of South Florida and an avid recreational fisherman. “There are some regions in the United States where the fishing season is historically open during a certain period of time, and now, the fish aren’t coming until after the season is over,” Shuler said.39 Reports of declining cobia catches along the Florida Panhandle prompted the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conversation Commission (FFWCC) to reduce the number of cobia that fishermen can catch in the northern Gulf of Mexico.40 Meanwhile, further south, cobia catches have been plentiful. WUFT News reported FFWCC Commission Chairman Brian Yablonski wondering, “Is it possible that all the Panhandle fish [those that typically migrate up into the Panhandle] have gone to Central Florida and are just hanging out there? It sounds like we have an abundance in one area and a dearth of fish in the other.”41

The science underlying why cobia are showing up in different areas of the Gulf of Mexico could be related to the warming water temperatures in the Gulf: In the winter of 2016, ocean temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico did not dip lower than 73 degrees Fahrenheit. Cobia are known to prefer warm water temperatures above 68 degrees Fahrenheit and to migrate north in the summer months, possibly to stay in their preferred water temperatures.42 The warm water temperatures in the Gulf could be contributing to cobia population migration changes.

But cobia is not the only commercially important species that has fled its typical habitat for more comfortable waters. Terry Gibson, a former charter fisherman and lifelong recreational angler, explained the importance of the king mackerel to anglers who travel across the nation to fish in Florida water. Gibson and others have noticed a shift over the past five years in the area that South Atlantic king mackerel and Gulf of Mexico king mackerel populations meet to mix. “I can show you my logs and my depth finder that [the water is] 2 or 3 degrees warmer almost all the time,” said Gibson, who believes climate change is playing a large role in the shifts of king mackerel populations.43

Gibson’s story matches the available science. Gulf of Mexico king mackerel are known to follow a similar pattern to that of cobia, spending summers in the northern part of the Gulf of Mexico and migrating south in the fall. At the same time, a separate Atlantic population of king mackerel also migrates south in the fall, and the two distinct groups eventually mix along the southeast coast of Florida. 44 Recently, however, scientists have shown that the mixing zone of the two populations of king mackerel had shifted to the south side of the Florida Keys, because the water is colder there.45

Fishermen have also noticed distinct changes to the sailfish migration, which have affected sailfish tournaments, jobs, and tourism revenue on the southeast coast of Florida. Thanks to catch-and-release fishing and a ban that prohibited destructive longlining in the straits of Florida, sailfish in the Jupiter area are one of the few populations that is not overfished.46 “Since 2003, you could almost guarantee a catch for a customer, and odds are you would probably would catch four or five [sailfish]. The colder it is, the better it is for this fishery, so you would go during nor’easter fronts,” Gibson said. “Today, the cold fronts are fewer and farther between, and we advertise like crazy when it does happen—really impacts local economy and the local sailfish tournaments.”47

Captain Randolph “Bouncer” Smith, a charter boat captain based out of Miami Beach, Florida, recounted similar stories of his 50 years in the charter industry:

In the 1970s [and as recently as 2005] in November and December you would have great sailfishing, and in January and February, everyone would jump out of their skin when there was a cold front. You would see 20 sailfish fighting over your bait. Now you don’t see those waves of sailfish, because it’s 80 degrees in winter. And it has a big impact. You used to see 30 charter boats, and every boat would be fishing two half-day trips through Easter. Now, with the lack of fish and warmer water, there might be five boats out of 40 in Miami who are able to fish.48

The sailfish, he noted, are now being seen off the coast of South Carolina and in areas where there are no established fishing tournaments or charter fishery clientele. Smith described how there are now many days in the winter where his customers have nothing to catch—hurting both his marketing ability and bottom line.

The same is true for Florida’s iconic tarpon fishery. Like sailfish, warmer water means that the tarpons’ migration patterns have shifted. Smith said that for him, the impacts have been substantial. “I’m forfeiting as many as 20 tarpon trips a month in the winter due to warmer weather. I had a guy who only worked nights for me, and now, he can’t make a living on tarpon, because I can’t guarantee [customers] we will catch fish. That guy literally went from a dependable income to scrounging,” Smith said.49 He believes the fish are comfortable staying north, because the water has gotten warmer.

The Mid-Atlantic

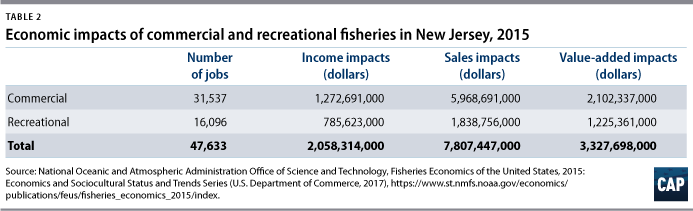

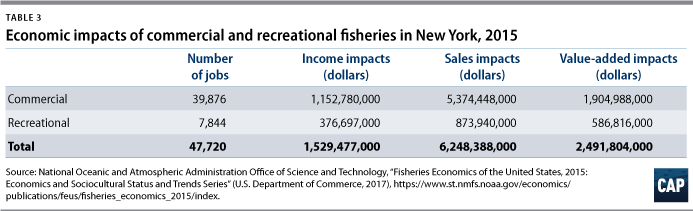

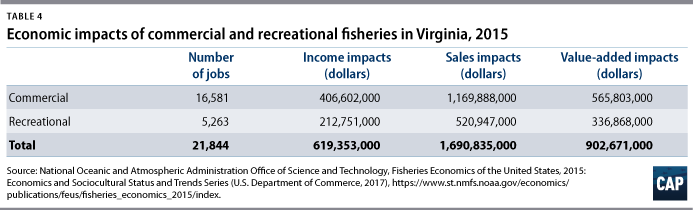

Along the Mid-Atlantic coast, commercial and recreational fishing represents an important economic driver. In 2015, the New Jersey fishing industry supported 47,633 jobs and generated $7.8 billion in sales; New York supported 47,720 jobs and generated $6.2 billion in sales; and Virginia supported 21,844 jobs and generated $1.6 billion dollars in sales.50 Yet, the fishing industries in all three states are under threat as researchers have found marine species to be shifting an average of 0.7 of a degree of latitude, or roughly 50 miles, north and 15 meters deeper in the water.51

Fishermen along the Mid-Atlantic states are noticing similar shifts in the distribution of marine fisheries as ocean temperatures in the Atlantic continue to warm.

Charles Witek, an attorney and avid saltwater angler, described his experience: “Summer flounder off the coast of New York are having poor spawning seasons; everyone is switching to black sea bass, which have become more abundant due to warming waters. I never caught a black sea bass in Long Island Sound, in all 27 summers that I lived in Connecticut. Now, they are an important part of the regional fishery.”52

Dolphinfish, commonly known as mahi-mahi, are a tropical fish traditionally caught between Florida and North Carolina. Now, they are increasingly found in the waters off New York, New Jersey, and Rhode Island.53 Witek said, “When I started fishing offshore in the early ‘80s, once in a while, someone got a dolphin[fish], but only when the warm canyon water came inshore. But they were targets of opportunity. … Now, I go out looking for dolphin[fish], and so do a lot of people. My wife and I go out and we catch all that we want. A friend of mine is a charter boat captain and is always talking about how he has dolphin[fish] on top chasing bait.” Scientific research on the species supports Witek’s observations, indicating that the wide-ranging species exhibits significant sensitivity to sea surface temperature and is caught recreationally only in waters warmer than 66.2 degrees Fahrenheit, while catch rates peak at 80.6 degrees Fahrenheit.54

Fishermen are also reporting noticing more of what they term “funny fish,”55 or unusual species showing up in their waters. “You can cast a net under lights in Virginia and catch Gulf shrimp—not grass shrimp, Gulf shrimp. The guys that are running oyster aquaculture, it’s becoming common to see Nassau grouper juveniles in the cage—you see it, and you think you’re the only one. Two weeks later, someone else has got one too,” explained Tony Friedrich, former executive director for Maryland’s Coastal Conservation Association and an avid recreational fisherman in Maryland. He added, “I know it’s hard to believe, but adult tarpon are becoming frequent summer visitors to the southern Delmarva Peninsula.”56 Witek also mentioned that “funny fish” are becoming the norm. “Juvenile red drum, croakers, 90-pound cobia have all been caught in New York and shouldn’t be this far north. We are starting to see more tropical fish on a regular basis.”57

These changes in the distribution of marine fisheries along the Atlantic coast, as well as changes throughout all U.S. waters, are compiled in the OceanAdapt portal, developed by Malin Pinsky’s research lab at Rutgers University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It illustrates the same trends that are being projected by climate models. The waters along the Northeast are predicted to increase between 1.8 degrees and 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit over the next 50 years. As waters warm, and poleward environments become more hospitable for tropical species, fishermen will continue to see more and more of these “funny fish.”58 Changes in forage fish abundance, habitat loss, and other changes to food web dynamics due to warming waters and changes in ocean chemistry may also contribute to shifts in marine species.59

New England: Maine and Massachusetts

The New England cod fishery is among the most historic American fisheries and one of the most troublesome. Decades of intense fishing pressure and overfishing caused the cod populations of the Northeast to almost disappear entirely.

The troubling reality of New England’s cod population

Cod has been a major economic industry for New England over the past 400 years. As fishing technology advanced, New England cod was fished extensively. Fishery managers have tried many different tactics to help the overfished cod populations recover, including using quotas, employing various mesh size restrictions, and closing areas to fishing. After MSA reauthorizations improved fishery management, the declining Atlantic cod numbers seemed to stabilize, but now the warming waters in the Gulf of Maine are threatening the recovery of the population.60 Strict management plans and catch limits slowly helped the stock recover, but cod populations in New England remain low.61 Research now suggests that climate change, specifically ocean warming in the Gulf of Maine, has hindered the cod population’s ability to rebuild.62

The Gulf of Maine has experienced a warming trend of 0.03 degrees Fahrenheit per year since 1982, and the Gulf’s sea surface temperature is warming 99 percent faster than the rest of the global ocean. Warm water hinders the ability of some fish to spawn63 and has also been linked to smaller body size.64

The lobster industry is among those in trouble. Lobster were once plentiful in southern New England but have largely disappeared from those rapidly warming waters over the past 10 years. Instead, the perfect water temperature for lobsters is now found off the coast of Maine, leading to a boom in Maine’s lobster profits. Between 2005 and 2014, Maine lobstermen earned an average of $321 million per year in revenue65 and supported more than 4,000 harvesting jobs in Maine since 2013.66 But fishermen are wary of the longevity of this success if the growing rate of carbon emissions is not addressed.67 “Lobsters have become our only major fishery,” said Richard Nelson, a commercial lobsterman in Friendship, Maine. “And it’s gotten to a bad point, because we have become so dependent on a single species and yet know so little about the impacts of warming and ocean acidification.”68

Nelson has been in the lobster fishery for more than 30 years. He also participated in Maine’s Ocean Acidification Commission, a multistakeholder group that formed in 2014 to assess the state of the scientific research on acidification, as well as the impact that acidification is having on commercially important species.69 “So far, what we know is that [the lobster] are affected by multiple stressors, such as warming and acidification together, a combination that has shown changes in respiration and swimming rates. We also see this same warming, when joined with nutrient runoff, helps create coastal acidification and also aggravates toxic algal blooms,” Nelson said. “People have to pay attention to the whole thing.”70

Lobsters aren’t the only species affected by climate change in Maine. Bill Mook, owner of Mook Sea Farm, one of the largest oyster producers in Maine, started noticing that his oyster larvae were experiencing disruptions and abnormal development. When this began affecting his business, his team started to treat the seawater used in their hatcheries to make it less acidic. Mook’s efforts worked, and his oysters grew properly with this treatment. He believes ocean acidification was to blame for the development problems. From 2003 through 2014, the Atlantic Ocean absorbed more than twice as much carbon dioxide than it did from 1989 through 2003, which has led to a measurable drop in pH.71

Mook also thinks that freshwater runoff is further reducing the pH of ocean water, making it harder for his oysters to grow. Northeast climate models predict an increase in annual average rainfall as climate change intensifies.72 This pattern of increased freshwater runoff is even changing the color of the water in the Gulf of Maine. William “Barney” Balch at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences has been sampling waters from the Gulf of Maine for more than 18 years and found that the fresh water’s yellow color competes with phytoplankton for the wavelengths they need for photosynthesis—ultimately impeding their ability to nourish themselves.73 Through his research and analysis, Balch has showed a potential fivefold decrease in primary productivity in the Gulf of Maine over the past decade.74 Reduced primary productivity could adversely affect fish and shellfish populations throughout the region.75

Mook also has to deal with additional food safety concerns linked to the warming climate. He said, “Warming waters also require additional steps to ensure our oysters are safe to eat, because pathogenic strains of the bacteria—Vibrio parahaemolyticus76—are more abundant. If oysters sit on the deck of the boat and are not immediately cooled down, the bacteria can multiply rapidly and cause people to get sick. This never used to be a concern.”77 For Mook, this is problematic, because occurrences of illness are much more likely to occur in oysters grown in higher-temperature water.78 In response, oyster growers and the Maine Department of Marine Resources have worked together to establish regulations aimed at maintaining safe-to-eat oysters.79

Meanwhile, in southern New England, fishermen are catching more black sea bass than they are legally allowed to land. Historically, states from Rhode Island to Maine have a much lower quota for black sea bass, since this species is normally found off the coast of North Carolina. Recently, though, black sea bass have been moving north in relation to the changing climate.80 This presents a management problem as North Carolina fishing vessels are forced to travel farther distances for their catch, while fishermen in the northern states are forced to throw the fish back overboard.

Alaska

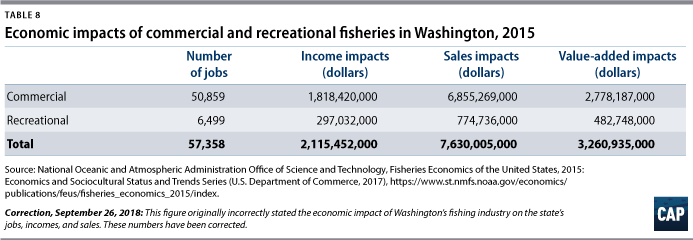

Alaskan commercial fisheries generated more than a third of the total national landings revenue, with $1.7 billion in 2015.81 Together, the commercial and recreational saltwater-fishing industry supported 58,848 jobs and generated more than $5 billion in sales.82 Many Alaskan fishermen come from multigeneration fishing families that rely on key species such as pollock, crab, and salmon to make their living.

Fishermen across the state have started noticing differences in the salmon runs, one of the most important commercial and recreational fisheries in Alaska. Heather Hardcastle, who has been fishing with her husband Kirk Hardcastle for more than 30 years, has seen a decline. She said, “The last five years in the state of Alaska, we’re seeing what we attribute to climate change, both marked differences in some salmon runs and marked differences in the size of salmon. Our salmon are smaller and smaller across the board and river by river, salmon are disappearing.”83 Her husband added, “This is the first year in southeast Alaska that it’s been this pronounced on the Taku River and the Stikine River. The amount of king salmon that were counted going up river were 7,000. It [the salmon run] was forecast to be 19,000 [salmon], which is already so much lower than 30,000, which has been the average. It’s the first year that the government actually shut down king [salmon] fishing in southeast Alaska—including sport fishing, subsistence, and commercial. And this is happening across all rivers across the state.”84

In addition to changes in the size and prevalence of king salmon, the sockeye salmon-run timings have changed. Heather said, “The bulk of the run seems to be shifting and has been getting later. Others are also experiencing later shifts. With sockeye salmon, there are eight distinct runs of sockeye, and you can tell the difference in the fish because they look physically different, because they spawn in different parts.”85 She noted that her family and other fishermen have seen shifts in all eight runs and in the timing of their returns. Heather has been working in the salmon industry her whole life and entered the fishery to help her father. She mentioned that he often talks of how they could time the particular sockeye salmon run down to the minute, “but now they are coming two, three weeks later,” she said. The Hardcastles’ experiences are consistent with current scientific opinion that a changing climate, specifically higher temperatures, will affect salmon-run timing, individual fish size, and population survival.86

Hannah Heimbuch, a fellow salmon fisherman in Alaska, echoed the Hardcastles’ concerns. She said that “it’s a big deal when you have guys that have fished for 70 years” and now they are totally changing their fishing practices “based on the temperature of the water.”87

While there is likely a variety of causes for the changes fishermen are seeing in the salmon fisheries, anthropogenic climate change and warming temperatures are certainly having an impact. 2016 was the first time in the historical record that no community in Alaska reached a low of -50 degrees Fahrenheit.88 And according to the National Climate Assessment, over the past 60 years, Alaska has warmed more than twice as fast as the rest of the country.89 Average annual temperatures have increased by 3 degrees Fahrenheit, and winters have increased by 6 degrees. Meteorologists in southeast Alaska are now predicting greater levels of precipitation, particularly rainfall, over the next decade. For the Hardcastles and other salmon fishermen in the area, this also means a greater freshwater lens, or the amount of freshwater floating on top of the saltwater in the rivers. “All the rain has caused the coho [salmon] to swim really deep, and the nets only go down 30 feet. So, we are literally missing the coho,” Heather Hardcastle said.90

Ocean acidification is also affecting Alaskan fisheries. Heimbuch said that part of her job has been to talk to people about acidification. “People [are] open to it,” she said. People are “thinking about, ‘How do I make investments and build a business to support my family?’ … It’s crazy for us not to [be] making plans to adapt to ocean acidification.” However, she stopped short of supporting looser regulations: “I don’t necessarily want to do that, because I think strict regulations protect our fisheries.” For Heimbuch, the bigger concern is the pteropods that will be affected by ocean acidification. Pteropods are tiny swimming snails that are a key component of the salmon’s diet91 and are thought to be particularly vulnerable to ocean acidification because of the composition of their thin, delicate shells.92 “Salmon are tightly tied into a complex food web. Pteropods will be impacted by acidification, and we don’t understand how that will shake up the food chain. A change in acidity can also impact the neurological ability of finfish,93 and my concern will be that we will see big changes in behavior.”94

In addition to salmon, the crab industry in Alaska is also experiencing the effects of climate change and acidification. Tyson Fick, the executive director of the Alaska Bering Sea Crabbers, described the difficulties the red crab population is expected to have over the next 20 years due to ocean acidification. “Last year was the highest temperature ever recorded in the Bering Sea,” Fick noted. “It’s funny, because some people could make an argument about warming being caused by natural cycles, but that argument has no place when it comes to acidification, because it’s chemistry. There’s only one place it comes from and there is zero room for debate that it comes from carbon emissions.”95

Fick explained that there will be winners and losers when it comes to ocean acidification and crab fishermen. He pointed out that golden king crab are more tolerant to lower pH water, while others, such as red king crab, can’t tolerate a lower pH. Fick said some fishery managers believe warm water forced the red king crab to gather together in certain colder areas, which he called “areas of prime conditions.” He added, “And they were easy to find, and everyone fished on top of them.” Since the crabs were forced into relatively small areas of cold water, crab catches were record-breaking, despite evidence that their populations had not increased. Frick said, “You look at last year, and the red king crab [harvest] was the highest you have ever seen. Survey results show low abundance, particularly low recruitment. So, what is that?”96 In the rest of the Bering Sea, according to Fick, crabs were very rare. This type of climate change-driven clustering can eventually lead to poor long-term outcomes, as it gives the impression there are more crabs than there actually are, making it difficult to set sustainable quotas.

West Coast: California, Oregon, Washington

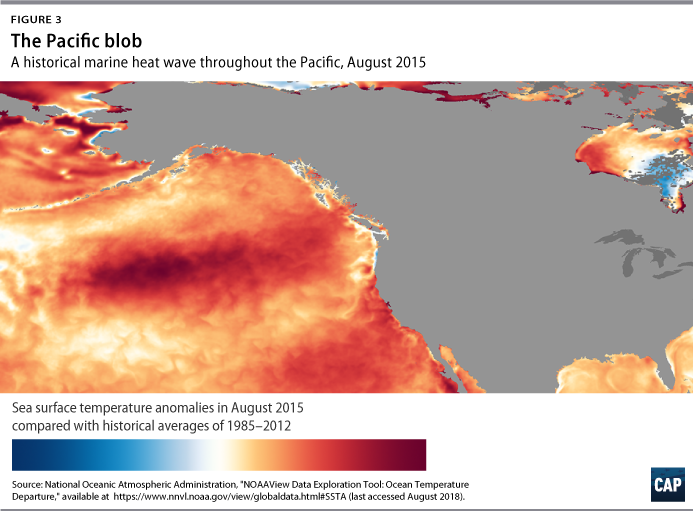

In the fall of 2013, NOAA detected a large mass of unusually warm water in the northeast Pacific Ocean. The warm water mass, later nicknamed “the blob,” was an average of 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than typical conditions, but NOAA scientists found some isolated areas that were up to 10.8 degrees Fahrenheit warmer.97 The blob was also persistent, lasting about three years,98 and partially created by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.99 It eventually disappeared on its own, but the ramifications remain; the blob provided a glimpse into what the ocean will look like if climate change is not controlled.100

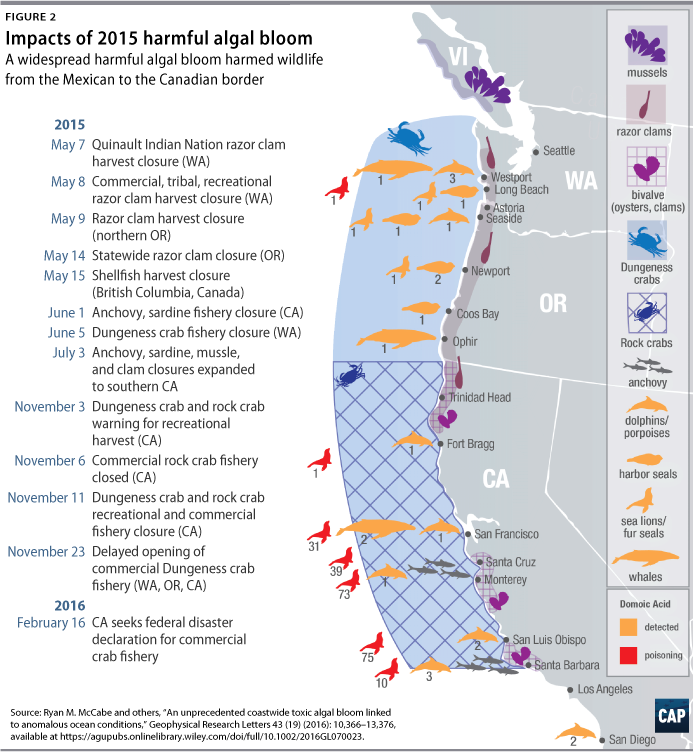

The blob caused or contributed to multiple unusual harmful events from Alaska to California during the three years it persisted, including increased mortality of sea lions,101 fin whales, humpback whales,102 and seabirds,103 as well as an unprecedented harmful algal bloom (HAB).104 HABs can be particularly harmful, since certain types of algae produce domoic acid, a potent neurotoxin. As filter-feeding organisms eat the algae, they also accumulate domoic acid, which is passed up the food chain and can poison marine mammals and people.105

In 2015, dangerous levels of domoic acid present in shellfish caused the regulatory agencies of Washington, Oregon, and California to close multiple commercial and recreational fisheries. The 2015 Dungeness crab closure cost the fishery an estimated $100 million when compared with the average value of the previous five years.106 Parts of the Dungeness crab fishery eventually opened but too late to be sold during the winter holidays, which are the traditional peak market season for Dungeness. Additionally, after national media publicized the HAB and subsequent “toxic crab”107 effect, buyers continued to shy away from West Coast crab and seafoods, further depressing earnings. According to Barbara Emley, an experienced crab and salmon fisherman and fishery representative on multiple West Coast fishery and ocean management councils, this was the first full-season closure of Dungeness.

Fishermen and crabbers along the Pacific Coast are still suffering. A federal disaster was declared in nine West Coast Dungeness crab and salmon fisheries for the 2015–2016 season.108 On February 9, 2018, Congress approved $200 million in federal aid109 for fisheries affected by disasters in 2015—many of which, such as the HABs and hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria, climate change either created or made worse. However, even this aid will not be able to make West Coast fishermen and fishing communities whole.

Emley fears that the future of West Coast fisheries is uncertain. Looking back on her 30 years in West Coast fisheries, she said, “I think we’re in trouble.”110 She said that most West Coast fishermen believe the blob will be back and that limited income potential and increasing uncertainty are preventing younger people from working in fisheries. Historically, West Coast fishermen were used to planning around the natural warm waters caused by the climatic pattern El Nino and would plan to catch different species that year. But, she said, the blob was different. No one had experience planning for an event like that. “This was toxic,” Emley said. “I don’t think humans can do anything [about the blob] besides reducing [our] climate change impacts.”