Introduction and summary

A dominant narrative that has come out of Turkey in recent years highlights how President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has consolidated control over the news media. Numerous human rights reports document how the Turkish government has sought to muzzle the press, whether by imprisoning journalists, eliminating news outlets, or overseeing the purchase of media brands by pro-government conglomerates.1 As the watchdog organization Reporters Without Borders writes, the regime has been “tightening the vice on what little is left of pluralism,” and Turkey is now “the world’s biggest jailer of professional journalists.”2

Despite this heavy censorship, two key trends have undercut President Erdoğan’s efforts to control the media landscape: rising distrust toward the media and increasing fragmentation in the ways that Turks get their news. The coronavirus outbreak in Turkey clearly illustrates these dynamics. Many Turks, doubting the integrity of traditional media, have viewed rosy coverage of Turkey’s response to the pandemic with skepticism and turned instead to social media, where, for example, a video claiming that the government was underreporting infections went viral.3 The pandemic has also underscored the fact that pro-government and opposition voters live in alternate media realities: The former hear that “the world is watching Turkey with admiration,” while the latter see videos of newly dug graves on social media.4 Yet while social media has offered an alternative to the pro-government voices that dominate television and print media, it too is a mixed bag of facts, half-truths, and incendiary misinformation.

The rapid reconfiguration of Turkey’s media space potentially has critical implications for the country’s domestic politics, its foreign policy, and President Erdoğan’s political future. First, current trends in online and traditional media will enhance the ability of partisans and foreign actors to spread misinformation, further fueling polarization and weakening political accountability. Rising misinformation and partisanship in the news media likely contributed to the Turkish government’s slow initial response to the coronavirus pandemic. Second, in the domain of foreign policy, the government’s manipulation of the media has curbed public scrutiny and thus lowered the domestic political cost of risky decisions. Finally, the transformation of the media could affect President Erdoğan’s ability to win—or coerce—electoral majorities: The government has won some votes through its censorship, but by driving Turks toward online outlets and social media, it has also created growing political vulnerabilities.

This report sheds light on the pervasive distrust and deepening fragmentation of Turkey’s media environment by analyzing data collected by a nationally representative survey in Turkey that was commissioned by the Center for American Progress. This survey, conducted by the polling firm Metropoll from May 24, 2018, to June 4, 2018, consisted of face-to-face interviews with 2,534 people in 28 provinces and used stratified sampling and weighting methods.5 The survey’s results reveal that even two years ago, distrust toward the media was already widespread, including among pro-government voters, and appeared to be rapidly driving Turks away from traditional offline news sources.6 These shifts in media consumption patterns have exacerbated the fragmentation of Turkey’s media landscape, widening partisan and generational divides in the ways Turks access information about politics.

While these trends are deeply worrisome, a fine-grained view of the media landscape reveals windows of opportunity for policy action in three key areas: collaborating with local media, investing in fact-checking organizations, and scaling up support for independent online news outlets.

Deep distrust and rapid change

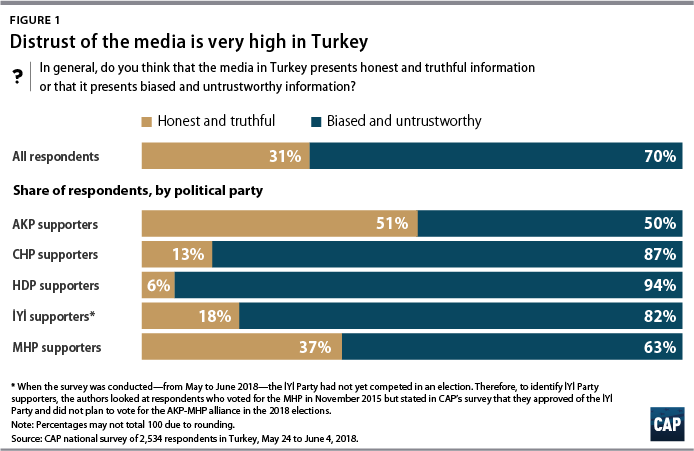

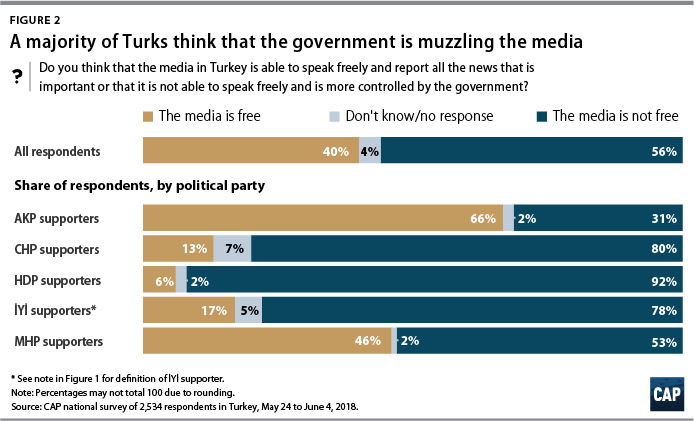

The Turkish media is currently embroiled in a crisis of public confidence that is fueling profound changes in patterns of news consumption. CAP’s survey, conducted in mid-2018, makes clear just how pervasive mistrust of the media is among the Turkish public. A remarkable 70 percent of respondents thought that the media “presents biased and untrustworthy information,” and a majority—56 percent—thought that the press “is not able to speak freely and is more controlled by the government.”7 As Figures 1 and 2 illustrate, doubts about the truthfulness and freedom of Turkey’s media have become acute, if not universal, among diverse opposition parties, including the center-left Republican People’s Party (CHP), the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), and the nationalist, conservative İYİ Party.8

Even more strikingly, many supporters of the government are aware that it is muzzling the press and putting its own spin on the daily news. CAP’s survey shows that among Turks who voted for the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) in November 2015, almost one-third—31 percent—agreed that the media in Turkey tends to be “controlled by the government.”9 Supporters of the AKP’s far-right, ultranationalist ally, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), are even more likely to acknowledge government censorship. Among respondents who voted for the MHP in November 2015 and planned to vote for the AKP-MHP alliance in 2018, 53 percent believed that the media was censored and not free.10 These data strongly suggest that many AKP and MHP supporters know they are not getting the full picture from the news media. When explicitly asked in CAP’s survey whether the media in Turkey is “able to speak freely and report all the news that is important,” a large share of pro-government voters said no.11

Other recent surveys further testify to the deep mistrust of news sources among a vast swath of the Turkish public. In a 2019 Ipsos poll, 55 percent of Turks reported that they have come to trust television and radio less over the past five years, and 48 percent said the same about online news websites and platforms.12 A 2019 survey by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism also found that 63 percent of Turks were “concerned” about false information on the internet.13 Notably, Turks ages 18 to 24 were just as likely to express concern as Turks ages 55 and above, and right-wing respondents were just as worried as respondents on the left.14 Unlike CAP’s face-to-face survey, these Ipsos and Reuters Institute polls were conducted online and consisted of respondents who were more urban and educated than the Turkish population as a whole.15 Thus, these polls are not nationally representative, but they indicate that among more urban Turks, certain concerns cut across age groups and ideological lines.

Pervasive mistrust of the media appears to be a driving force behind rapid changes in the ways that Turks get their news. In particular, mistrust is pushing citizens toward online media sources that tend to be more independent of the government. A statistical analysis of CAP’s data found that if an individual thinks that the media in Turkey is generally untruthful, one can be 95 percent confident that they are less likely to rely on television as their primary source of news—and 99 percent confident that they are more likely to rely on social media.16 These statistical results hold even when one controls for a respondent’s party preferences and eight different demographic variables.17 What is more, the effect of distrust is quite large and quantifiable: All else being equal, the likelihood of relying on television for news is 79 percent for Turks who trust the media but 66 percent for those skeptical of the media.18

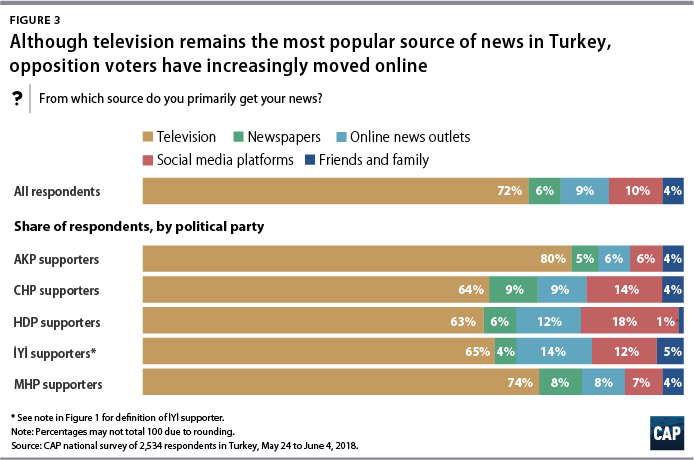

In this context, print newspapers and television—two news sources that the government can regulate more easily than online media—have suffered sharp declines in popularity, although television remains by far the most widely used news source. Domestic newspaper circulation fell by almost half—44 percent—from 2013 to 2018, a span of time during which the government clamped down on press freedom with theretofore unprecedented intensity.19 More recently, the coronavirus has dealt yet another punishing blow to newspaper sales in Turkey, with the circulation of different papers declining by 22 percent to 60 percent from March 2020 to May 2020.20 As for television, a comparison of two nationally representative surveys—the 2015 Turkish Election Study (TES) and CAP’s 2018 poll—shows that the percentage of Turks who cited television as their primary source of news dropped from 87 percent in 2015 to 72 percent in 2018, a decline of 15 percentage points in three years.21 Meanwhile, during that same period, reliance on social media for news increased fivefold, from 2 percent to 10 percent.22 Long-term trends, including a steady decline in overall television viewing since the mid-2000s, can only partially explain these changes.23 Government censorship and pervasive mistrust have been important drivers, and as the following section will detail, these shifts have resulted in a fragmented and fractious media landscape.

The fragmentation of Turkey’s media landscape

In recent years, three key trends have led to increasing fragmentation in patterns of news consumption among the Turkish public: deepening partisan cleavages, widening generational divides, and the surprising staying power of local newspapers.

Partisan divisions

In just the past few years, Turks have become much more divided along party lines in terms of their main sources of news and the media brands that they follow. A comparison of the 2015 TES and 2018 CAP survey reveals that the percentage of Turks who cite television as their primary news source has fallen dramatically, especially outside the AKP’s voter base. From 2015 to 2018, this figure declined by 10 percentage points among AKP voters, by a staggering 21 percentage points among CHP voters, and by 30 percentage points among HDP voters.24 Conversely, usage of social media for news has grown rapidly, in particular among non-AKP voters. From 2015 to 2018, the percentage of Turks who relied on social media as their main source of news increased by 4 percentage points among AKP voters, yet it rose by 11 percentage points among CHP voters and by 16 percentage points among HDP voters.25

Differences in media sources also contribute to the schism between the MHP and the İYİ Party, which formed in 2017 as a breakaway faction of the MHP. According to CAP’s data, in 2018, İYİ Party sympathizers were more likely than MHP supporters to cite social media or online outlets as their primary source of news—25 percent vs. 14 percent—and they were also less likely to rely on television—65 percent vs. 74 percent.26 The fact that İYİ Party supporters, like other opposition groups, have been able to carve out a distinctive niche in the news media indicates that despite the dominant role that television continues to play in Turkey, President Erdoğan’s control of the media landscape is slipping.

These differences between parties suggest that the opposition’s hunger for independent news sources may have pushed it online. CAP’s statistical analysis found that if an individual supported the HDP in 2018, one can be 95 percent confident that they were more likely to rely on online news and not on television—even after controlling for trust in the media; ethnicity, defined as being Kurdish; and numerous other demographic variables.27 Similarly, if a respondent supported the opposition’s Nation Alliance, led by the CHP and İYİ Party, in 2018, then all else being equal, they were significantly more likely to use social media as their primary news source.28 Regardless of whether party loyalties are causing differences in media choices, the data show that Turkey’s warring political camps inhabit increasingly separate media spheres.

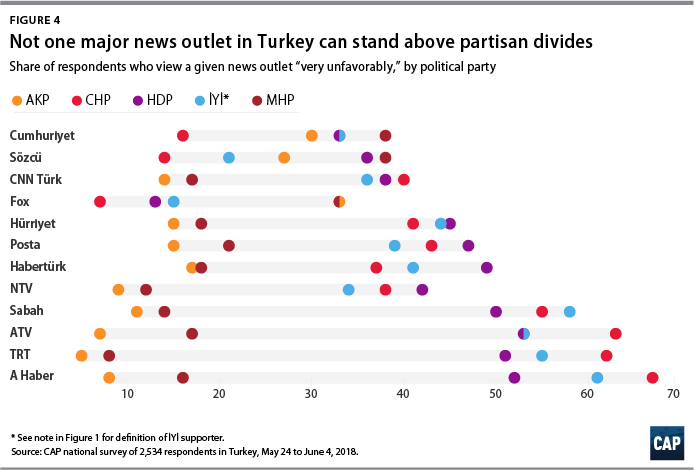

Perhaps the most noteworthy and concerning feature of Turkey’s fragmented media landscape is that there is not one major news outlet that can stand above the partisan fray. Even in the hyperpolarized context of the United States, a 2019 Pew Research Center survey found that three outlets—the BBC, PBS, and The Wall Street Journal—are all trusted more than distrusted by both Democrats and Republicans “for political and election news.”29 In Turkey, however, CAP’s data show that supporters of different parties are starkly divided in their perceptions of all 12 media brands about which they were surveyed.30 As Figure 4 illustrates, for each of these brands, there was a gap of at least 20 percentage points among AKP, CHP, HDP, İYİ, and MHP supporters in terms of whether they regarded the outlet “very unfavorably.”31 At the extreme, 67 percent of CHP voters viewed the pro-government outlet A Haber “very unfavorably,” while just 8 percent of AKP voters thought the same.32 Turkey’s media is so fractured that the country does not have a single widely trusted news outlet, and this void opens the door to partisan misinformation, political polarization, and a lack of government accountability in foreign and domestic policy.

Generational divides

While partisan divides have widened, so too have generational ones, as younger Turks have become increasingly reliant on social media for news and information. From 2015 to 2018, the share of Turks ages 18 to 34 who cited social media platforms as their main source of news grew by 11 percentage points, compared with just 4 percentage points among Turks ages 55 and above.33 While the proportion of Turks ages 18 to 34 who rely primarily on social media for news remains fairly low at 15 percent, this figure has grown rapidly, more than tripling in a three-year period.34 And whereas 83 percent of Turks 55 years old and above get their news mainly from television, this statistic is much lower, at 64 percent, among Turks ages 18 to 34.35

Younger and older Turks even tend to use different social media platforms, suggesting that the two groups form part of largely separate online communities. According to a 2019 poll by the Reuters Institute, Turks ages 18 to 24 were more likely to say that they had used Instagram for news in the past week than those ages 55 and above by a margin of 15 percentage points.36 In addition, this younger demographic was less likely to report using Facebook for news by 24 percentage points.37

The growing divergence of younger and older Turks into discrete media spheres may reinforce generational divides over key political questions. As CAP’s previous research has underscored, younger AKP voters have been consistently more critical of Erdoğan personally and the AKP overall than older AKP voters, and in CAP-commissioned focus groups held in late 2017, they often characterized the president as the “best of the bad options.”38 If AKP youth self-select into a social media ecosystem less favorable toward President Erdoğan, they may in turn grow farther apart from older AKP supporters. Within other political parties as well, the tendency of Turkish youth to use social media for news may be feeding a disconnect between party establishments and their younger voters.

Local vs. national news

The surprising survival of local newspapers in Turkey further demonstrates that the media landscape—far from becoming consolidated and centralized—remains fragmented in key respects. In many countries, national media organizations have amassed control over an increasingly large share of the market, and plummeting newspaper circulation has taken a particularly heavy toll on local news organizations. In the United States, for instance, more than 1 in 5 local papers closed from 2004 to 2018.39 In Turkey, by contrast, the number of local papers actually increased by 31 percent from 2005 to 2018.40

Local papers in Turkey have by no means flourished, but they also have not suffered as much as Turkey’s national papers from the sharp decline in circulation in recent years. From 2013 to 2018, annual circulation fell by 45 percent for national newspapers but a more modest 33 percent for local papers.41 As of 2018, local newspapers represented 18 percent of total domestic circulation—the greatest share of any year since 2005, when the Turkish government began publishing data.42 Turkey’s local press was responsible for the circulation of 4.37 million newspapers per week in 2018, and on average, each local paper had a weekly circulation of 1,950 copies.43

These local newspapers have very limited political influence. Often, the most that they will do is call on a prominent national politician from their province to deliver projects or public services to his or her home district.44 They also depend significantly on public announcements and advertisements for income, and the state’s Press Advertisement Institution (BİK), which administers these contracts, is prohibited by law from giving them to news outlets that employ journalists being tried on terrorism-related charges—charges often used by the government as a political cudgel to silence dissidents.45 Nonetheless, local newspapers do have a degree of independence, and ownership data published by BİK, albeit incomplete, provide anecdotal evidence to suggest that many of these papers are locally owned, rather than being part of pro-government media conglomerates.46 The endurance of local newspapers thus suggests that many citizens are hungry for independent information and that pockets of independence do persist.

Political implications

The changing patterns of news consumption discussed above potentially have major ramifications for Turkey’s political divisions and pandemic response, Turkish foreign policy, and President Erdoğan’s political fortunes.

Misinformation, polarization, and the coronavirus pandemic

Scholarly research suggests that current media trends in Turkey will exacerbate already high levels of misinformation, thereby intensifying partisan polarization, eroding political accountability, and worsening crises such as the coronavirus outbreak.

Rising usage of social media for news, in particular, appears often to be fueling misinformation among the Turkish public. In a study based on nationally representative survey data from Turkey, three scholars at Koç University, Simge Andı, S. Erdem Aytaç, and Ali Çarkoğlu, found that “ceteris paribus, those who use social media are more likely to be misinformed, but simultaneously are more confident of their incorrect knowledge about politics.”47 In 2015, only about one-third of Turks—35 percent—reported using social media on a weekly basis.48 But as social media usage rises, citizens’ political attitudes and voting behavior may be increasingly influenced by “inaccurate information that is deliberately or inadvertently spread” online.49 Notably, the Kremlin-backed outlet Sputnik Türkiye has proven remarkably adept at spreading misinformation online to advance Russian interests.50 Ironically, then, Turks who turn to social media to get the facts and escape the pro-government bias of traditional news sources are more likely to be misinformed as a result. Individuals have very few options for accessing independent and trustworthy information about politics, and the proliferation of often incendiary falsehoods on social media may only aggravate polarization.

The growing usage of partisan media outlets is yet another trend fanning the flames of misinformation in Turkey. Particularly since 2007, partisan voters have increasingly gravitated toward reading “highly biased newspapers.”51 And in an analysis of newspaper consumption during Turkey’s June 2015 election campaign, Mert Moral, a scholar at Sabancı University, and Çarkoğlu found that voters who read a newspaper biased toward their party actually became “less knowledgeable about their own party’s policy offerings.”52 If, for instance, an AKP supporter read a pro-government newspaper such as Sabah every day during the election campaign, on average their score on a test about the AKP’s policy positions dropped by 33 percentage points—or two questions out of six.53 Interestingly, “less explicit types of media bias” appear to be driving this effect; for instance, a pro-CHP newspaper is much more likely to quote CHP politicians, who will present their policies in the best possible light, than to critically analyze the party’s positions.54 Given that voters are increasingly choosing to read biased newspapers, they may lack the political knowledge that they need to critique their party leaders and hold them accountable on policy issues.55

Perhaps most seriously, rampant misinformation and the partisan media’s failure to hold the government accountable contributed to Turkey’s slow and opaque initial response to the coronavirus pandemic.56 False news stories—including claims that the popular disinfectant kolonya or simply “Turkish genes” would protect Turkey from the virus—undercut scientific evidence about the impending threat to public health.57 Misinformation also circulated about how unproven drugs, onions, and even hair dryers provided effective home remedies.58 At the same time, the government’s tight control of pro-AKP news sources meant that these outlets were not holding the government’s feet to the fire before its core base by demanding a swift and transparent pandemic response. Pro-government sources such as A Haber praised Turkey’s official response as an “example to the world” in late March, when more vigorous action was clearly needed.59 The government also avoided scrutiny by clamping down still further on any signs of journalistic independence, prosecuting a popular television news anchor and detaining 10 journalists for their coronavirus-related coverage.60

Ineffectual foreign policy oversight

The government’s restrictions on the news media have sharply curtailed the space for critical, apolitical examination of not only domestic but also foreign policy issues, thereby undermining Turkish national security.61 The current media environment should be troubling for Turkish foreign policy experts and Turkey’s NATO allies, given that an independent media can serve as a check on foreign policy decision-making, particularly in protracted wars such as the Syrian conflict.62 Two recent episodes vividly demonstrate how the government’s manipulation of the media has helped reduce public scrutiny and thus been a factor in allowing President Erdoğan to make risky foreign policy decisions.

The first episode concerns President Erdoğan’s decision to acquire the Russian S-400 missile defense system in July 2019. In Turkey’s hyperpartisan media environment, the government was not held accountable to its voters for the drawbacks of the S-400 purchase, since pro-government news outlets presented the public with misleading information to justify the S-400’s superiority.63 CNN Türk and Yeni Şafak, for instance, saturated viewers with highly technical information about the S-400’s superior radar range and quicker set-up speed.64 Yet they did not weigh other consequential considerations about the defense system’s noninteroperability with NATO assets and the anger and subsequent fallout the system’s purchase would provoke in the U.S. Congress. Indeed, President Erdoğan’s acquisition of the S-400 has triggered Turkey’s removal from the program to develop and build the F-35, the fifth-generation fighter jet to be operated by key U.S. allies. That removal undercuts Turkey’s ability to counter Russian airpower, particularly in northwestern Syria, and has dealt a serious blow to the prestige and commercial prospects of Turkey’s nascent domestic aerospace and defense industry. These were eminently knowable risks, yet they went largely unreported in the pro-government Turkish media.

A second episode that demonstrates the government’s capacity to curb media criticism came in the wake of an airstrike on February 27, 2020, in the Syrian province of Idlib, which killed 34 Turkish soldiers—the deadliest single day for the Turkish military since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011.65 In the aftermath of that attack, the government blocked social media platforms for more than 16 hours: Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter became unreachable, while traffic on WhatsApp and YouTube ground to a near halt.66 The shutdown or slowdown of these sites left Turks with few ways to access independent information, effectively cutting off public deliberation about Turkey’s Syria policy. Pro-government outlets, meanwhile, gave extensive airtime to AKP officials, allowing them to craft the public narrative, and even highlighted “comforting news” to ease public anxiety.67 Such a media environment, in which it is very difficult for journalists, experts, and the public to look critically at foreign policy issues, jeopardizes Turkish national security.68

Erdoğan’s uncertain future

The increasing fragmentation of Turkey’s media sphere has potentially major implications for Erdoğan’s political fortunes. On the one hand, Erdoğan’s efforts to coerce more positive media coverage have won him votes. While many observers assume that the Turkish media is an echo chamber that merely reinforces existing partisan preferences, scholars Ali Çarkoğlu and Kerem Yıldırım found in a recent study that media coverage in fact “has a substantial influence on vote choice.”69 The authors looked at data from nationally representative surveys, in which Turks were asked about their preferred party and choice of newspaper before an election and then asked afterward about the party for which they had ultimately voted. The results showed that when a respondent’s chosen newspaper gave a certain party favorable coverage, they became significantly more likely to switch sides and vote for that party. For instance, if an individual originally planned to vote for the CHP but then read a pro-AKP newspaper such as Posta or Sabah, they became more likely to change their mind and vote for the AKP. And notably, as of 2015, sizable minorities of CHP voters did read pro-AKP papers.70 This research and related studies suggest that the AKP’s control over television, radio, and print newspapers has allowed it to bolster its public support.71 As Çarkoğlu and Yıldırım note, the partisan competition to shape media content and the government’s tutelage of the media are “not in vain.”72 Media coverage, at least in newspapers, has “a critical impact on voters,” even in a severely polarized country such as Turkey.73

On the other hand, trends in media consumption have created two growing political vulnerabilities for Erdoğan. For one, as Turks increasingly migrate toward online news sources that the government is less able to control, they may be exposed to more critical content and thus become more likely to oppose the president. A statistical analysis of CAP’s survey data found that Turks who relied on online platforms or social media for news, as opposed to television, were significantly more likely to disapprove of President Erdoğan, even after controlling for their vote in the November 2015 elections. That is, imagine two Turks who both voted for the AKP in 2015 and are equivalent across a range of demographic characteristics; if one relies on online news or social media while the other relies on television, one can predict with 95 percent confidence that the former is more likely to disapprove of President Erdoğan.74 This finding suggests that usage of online news may engender increased disapproval of Erdoğan, that misgivings about the president may cause Turks to turn to online sources, or both of the above. Neither explanation is good news for Erdoğan, though the former is much worse. The move toward online news and social media thus has the potential to undermine the president’s popularity even within his own camp.

For the moment, however, that threat is contained. AKP voters have largely remained reliant on traditional news sources such as television, rather than switching to online platforms. Even though almost one-third of AKP supporters viewed the Turkish press as unfree, this perception does not seem to have motivated major changes in media consumption habits, with just 12 percent reporting that they get their news primarily from online outlets or social media.75 Still, over time powerful societal trends are likely to push increasing numbers of AKP voters, especially young voters, toward online news sources that the government is less able to control. Indeed, given global trends toward online news in general and social media in particular, President Erdoğan and the AKP may be fighting an uphill battle in this regard.

Perhaps the more immediately significant vulnerability for President Erdoğan is that online news and social media could facilitate the formation of breakaway factions from the AKP, in the same way that these platforms probably aided the İYİ Party’s split from the MHP.76 In the past few months alone, Erdoğan has faced two such threats from within the conservative camp. Ahmet Davutoğlu, who previously served as foreign minister and prime minister in successive AKP governments, launched the new Future Party in December 2019.77 Probably an even greater threat to the president is the Remedy Party, founded this March by Ali Babacan, who held top posts in AKP governments from 2002 to 2015.78 Much like Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu and other opposition figures, these two leaders have sought to use online platforms such as Medyascope and social media networks to win over disaffected and especially young voters.79 Given that the AKP and MHP won a narrow victory in the 2018 parliamentary elections with 54 percent of the vote, the loss of just a few percentage points to these new parties could deprive the government of its legislative majority and reinvigorate the opposition.

President Erdoğan’s vulnerabilities help explain why his government has gone to such great lengths to rein in critical voices on social media. The AKP’s efforts in this vein have a long history: From 2007 to 2010, the government banned YouTube, and during the 2013 Gezi Park protests, it began to “throttle” Facebook and Twitter, dramatically slowing internet traffic on these sites.80 Most recently, in April 2020, the government prepared a draft law that would grant the state “direct control” over social media platforms, going even beyond the current system, wherein the government removes hundreds of Twitter accounts each year by submitting requests to Twitter.81 Although the proposed legislation was subsequently withdrawn, many in the opposition fear that the government will soon push for similar measures. Furthermore, in late March and April, Turkey’s Interior Ministry detained more than 400 social media users for “provocative” posts about the coronavirus.82 Yet this repression has also demonstrated social media’s resilience, as an online campaign emerged to press the government to release the detainees.83

Policy recommendations and conclusion

This report highlights numerous troubling developments in Turkey’s media landscape. Distrust in the media has reached crisis proportions, with fully 70 percent of Turks viewing the media as dishonest.84 These doubts have formed the backdrop for rapid shifts in how Turks access political news and information, as citizens turn toward online outlets and social media platforms that are more independent of government control but are themselves often rife with misinformation. Such changes have created an increasingly fragmented media landscape, in which Turks of different political parties, ages, and regions are consuming news from very different sources. Unfortunately, many of these sources are unreliable, and none enjoys trust across the political spectrum.

The political repercussions of these trends will deeply affect both Turkey and its Western allies. Indeed, these same challenges, including distrust of the media and severe political polarization, are afflicting numerous other NATO countries, from Poland to the United States.85 The growing prevalence of misinformation may further aggravate partisan divides and weaken accountability. Already it has undermined Turkey’s response to the coronavirus pandemic. The Turkish government’s muzzling of the media has also harmed the nation’s security by debilitating public oversight of foreign policy decision-making and creating fertile ground for Russian influence operations. At the same time, this media crackdown may have profound consequences for Turkey’s domestic balance of power, as it has driven many citizens toward the more open world of social media and thus created new vulnerabilities for President Erdoğan.

A detailed examination of Turkey’s changing media landscape points to three priority areas for Turkish and international actors who seek to support democratic governance and anchor Turkey within the transatlantic alliance. First, Turkey’s local papers, which command nearly one-fifth of total newspaper circulation, offer a frequently overlooked opportunity to support independent journalism. At present, many local papers lack the resources and training to conduct high-quality reporting. Grant-making programs should work with professional organizations, including local chapters of the Turkish Journalists Association (TGC) and the Journalists’ Union of Turkey (TGS), to help set editorial standards, provide legal support for journalists, and connect local reporters with independent national outlets that often lack original, locally produced content.86 Funders should also integrate local newspapers into their work with civil society organizations (CSOs). For instance, they could collaborate with journalists to publicize a local CSO’s activities or the resources it offers, supporting the local paper at the same time.

Second, Turkish and international actors need to counter the swelling tide of misinformation on social media—without opening the door to further government censorship. An especially promising approach is investing in fact-checking organizations; some of these organizations have already gained traction in certain parts of Turkish society and been cited publicly by current and former parliamentarians from different parties.87 Grant programs could amplify the impact of such efforts by providing targeted funding to fact-check news stories about priority issues, such as refugees and other vulnerable groups, climate change, or Turkish foreign policy.88 Inflammatory falsehoods about Syrian refugees are particularly common and have even appeared on newspapers’ front pages, as the Hrant Dink Foundation’s hate speech tracker has documented.89 Grant programs should also train journalists to use content verification technologies so that they can serve as the first line of defense. For example, the European Union could proactively share expertise and technology from its own projects to combat disinformation, such as the EU-funded platform InVID, which allows journalists to quickly authenticate video content spread via social media.90 From 2016 to 2019, the National Endowment for Democracy increased its level of funding in support of independent journalism in Turkey sixfold; this increased level of funding should be maintained.91

Most of all, existing efforts to support independent online news outlets are not commensurate with the importance of this challenge. Turkish citizens and youth in particular are increasingly turning to online sources for more independent perspectives, but the Kremlin-backed outlet Sputnik Türkiye has often been more successful than its Western-funded competitors at attracting an audience. On Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube, Sputnik Türkiye has a total of 1.49 million followers—almost twice as many as Gazete Duvar and more than three times as many as Bianet or Medyascope, online outlets that have received Western support.92 Funders should anticipate that independent outlets will need considerably more resources than a typical CSO to make their voices heard in a noisy and competitive media landscape.

Grant programs can also target their resources more effectively by earmarking funds for reporting, rather than commentary. Many independent news outlets, such as T24, produce an abundance of commentary, because it is cheaper and less legally perilous to employ part-time columnists instead of full-time, professional reporters. Yet what Turkey’s media needs is more resources for the latter. Funding should focus in particular on supporting nonpartisan reporting on the Kurdish question,93 including the work of local correspondents. As a precondition for these efforts, funder organizations should adapt their eligibility criteria so that grants can cover basic expenses, such as journalists’ salaries, and consider supporting media outlets that are not registered as nonprofits.94

Foreign funding for journalism can be a double-edged sword, as this support can be attacked by domestic populists and nationalists, who lash out at organizations with international funders. Still, these concerns pale in comparison with the need to allow news organizations to keep the lights on and maintain their independence.95 To achieve more sustainable results, grant-makers should help independent media platforms become financially self-sufficient by pointing them toward innovative funding models that have been successful in other backsliding democracies, such as Hungary and Poland.96

While the state of Turkey’s news media is sobering, this report also reveals that various Turkish actors are creating space for a less polarized public discourse. Above all, human rights organizations have courageously defended freedom of expression and the press, and many journalists continue to try to report the news fairly, often at great personal cost. Both Turkish and international actors can play a constructive role by supporting local efforts, as well as pushing back against government censorship. Yet the trends toward distrust, fragmentation, and misinformation in Turkey’s media landscape will be difficult to overcome; they should be deeply concerning for Turkish citizens, for Turkey’s allies, and even for President Erdoğan.

About the authors

Andrew O’Donohue is the Carl J. Friedrich Fellow and a Ph.D. student in Harvard University’s Department of Government, as well as a research fellow at the Istanbul Policy Center.

Max Hoffman is the associate director of National Security and International Policy at the Center for American Progress, focusing on Turkey and the Kurdish regions.

Alan Makovsky is a senior fellow for National Security and International Policy at the Center for American Progress and a longtime analyst of Middle Eastern and Turkish affairs.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Simge Andı, Rana Elif Aydın, S. Erdem Aytaç, Cem Bico, Ali Çarkoğlu, Mert Moral, Edgar Şar, Michael Werz, and Kerem Yıldırım for conversations and other communications that added immensely to this report. We also wish to thank Carl Chancellor, Meghan K. Miller, and Keenan Alexander for their valuable editorial and art assistance. Metropoll Strategic and Social Research contributed invaluably to this report through its excellent conduct of the nationwide polling and associated focus groups. Andrew O’Donohue is indebted to his colleagues at the Istanbul Policy Center (IPC), especially Senem Aydın-Düzgit, for their support throughout this research project, as well as IPC intern Bilgehan Balık for her research assistance. Finally, this research is made possible by the generous support of Stiftung Mercator.