Introduction and summary

To succeed in today’s economy, organizations must capitalize on the skills, knowledge, abilities, and experience of their employees. Research shows that investments in human capital improve organizational performance—including team effectiveness, employee retention, and innovation—in both the private and public sectors.1 In other words, companies that attract and develop strong employees by prioritizing recruiting, investing in professional growth opportunities, and building positive workplace cultures tend to have greater efficiency and better outcomes.2

To build effective human capital systems, organizations must use these proven strategies, as well as be dynamic. Employers must adapt to new landscapes: shifts in the labor market, new technologies, and advancing communication methods all require employers to reexamine the way they approach recruiting, developing, and retaining their employees.3 Within the past two years, for example, 79 percent of job seekers have used online resources to search or apply for a new role—tools that were nonexistent in earlier decades.4

Many entities in both the private and public sectors recognize that just as innovation shifts the nature of their work, technology and new ideas must also influence their human capital systems. In response, many organizations have modernized their recruitment and professional development practices in order to recruit, develop, and retain excellent employees.

While there are many techniques to cultivate top talent, many organizations with effective human capital systems embrace the same best practices. They attract quality talent using strategic recruitment systems that engage top candidates through targeted outreach and technology.5 They also develop selection processes that evaluate candidates’ fit and expected performance on central job responsibilities.6 To retain highly sought employees, effective organizations foster positive workplace cultures, compensate their employees at competitive levels, and create opportunities for professional growth to ensure that candidates thrive and mature within the organization.7 In addition to an overarching human capital system, many effective organizations also devise specific strategies to recruit and support candidates who come from diverse backgrounds.8

To better understand how school districts’ human capital systems compare with the best practices employed in other sectors, the Center for American Progress performed the first national survey of school districts’ human capital practices. CAP surveyed a sample of 108 nationally representative school districts and asked them to describe how they recruit new talent, select whom to hire, induct new teachers, develop teachers’ skills, and measure and reward teachers’ success in the classroom.

The results of the survey demonstrate that many public school districts have not kept pace with the human capital innovations and best practices of other fields. CAP’s analysis highlights challenges within the current landscape of human capital practices in school districts across the country:

- School districts’ recruitment strategies are hyperlocal, untargeted, or nonexistent.

- School districts’ application and selection processes often emphasize static application materials—such as written applications, resumes, and proof of certifications—over performance-based measures.

- School districts do not provide new teachers with substantive mentoring or onboarding opportunities to build new skills critical to their roles.

- School districts do not provide teachers with enough opportunities for professional development or access to professional learning systems that support teachers’ continuous growth.

- School districts do not compensate teachers similarly to college-educated professionals in other fields or provide teachers with the resources they need to do their jobs well.

- School districts do not strategically recruit diverse candidates or create inclusive, supportive environments to retain them.

School districts across the country must compete with the companies that have more sophisticated human capital systems and offer more competitive salaries. As a result, school districts face obstacles to recruiting and retaining excellent, diverse talent.

Based on CAP’s analysis, this report offers the following recommendations for school districts to improve their approach to recruiting, training, and retaining excellent teachers:

- School districts should devote more time and resources to intentional recruitment.

- School districts should include performance measures in their application and selection processes.

- School districts should provide new teachers with opportunities to build their skills and gradually assume increased responsibility.

- School districts should offer teachers opportunities and time to grow, as well as implement professional learning systems that support teachers’ continuous growth.

- School districts should ensure that teachers’ compensation is similar to that of other professions requiring the same level of education and provide teachers with necessary teaching resources.

- School districts should prioritize teacher diversity and develop strategies to attract and retain teacher of color.

This report provides a direct comparison of the human capital practices in public school districts with best practices elsewhere to underscore the need to reform district human capital practices in order to attract and retain top talent.

A comparison of school districts’ human capital systems with those of other fields

School districts’ human capital practices lag behind those of high-performing organizations, affecting their ability to attract and retain talented professionals. This section details the findings of a nationally representative survey of school districts’ human capital practices, juxtaposing the findings with examples of best practices in other fields.

School districts’ recruitment strategies are hyperlocal, untargeted, or nonexistent

Teacher quality is the most important in-school factor related to students’ academic success, and low-income students benefit most when taught by skilled teachers.9 Just as in other sectors, strategic recruitment in the education sector is critical to identify candidates who are likely to succeed. Strategic recruitment increases overall teacher quality, reduces shortages and turnover, and minimizes the need for additional training. CAP’s human capital systems survey, however, found that most school districts use hyperlocal and passive recruitment strategies, meaning that they do not actively seek out new candidates from across the country. Additionally, they do not allocate enough time or resources for recruitment.

Fast facts: School districts’ recruitment practices

- An average school district has 1.8 employees assigned to recruitment and a student population of 3,721.

- Ninety-four percent of districts post job openings on their district websites, but only 30 percent of districts post job openings on social media networks.

- Sixty-seven percent of districts post job openings on websites of Schools of Education. Of those districts, only 29 percent post job openings outside of the state in which the district is located.

- Only 21 percent of districts post job openings on websites of alternative certification/preparation programs.

- Fewer than half of districts travel to colleges or universities to recruit at job fairs and other events. Among districts that travel to colleges and universities to recruit at job fairs and other events, only 22 percent travel outside of the state in which the district is located.

School districts’ recruitment policies and systems lag behind those of other industries and do not employ accepted best practices. For example, leveraging new technology for recruitment is common across other sectors and fields: 96 percent of job recruiters outside the education sector nationwide report using social media to reach out to candidates in the recruiting process.10

Additionally, organizations—even the most competitive—benefit from aggressive recruitment strategies that cultivate personal relationships with candidates. For example, FirstMerit Bank proactively identifies and contacts potential recruits. Rather than using general job postings, the company asks all of its employees to participate in the recruitment effort, increasing the reach of those searching for talent. Even before positions are posted publicly, all employees at FirstMerit Bank identify and personally contact prospective candidates, building a pool of candidates for future job placements. Therefore, FirstMerit employees are always looking for potential employees who could add value to the company. Furthermore, FirstMerit Bank dedicates a significant portion of its budget to direct recruiting strategies. The company sends top prospects cookies and cards on their birthdays and New Year’s Day with the aim of contacting candidates at moments when they may be rethinking their career path.11

The consulting firm Deloitte is another leader in innovative, targeted recruitment. In addition to a robust employee referral program, Deloitte relies on social media to attract those outside the firm’s network—often increasing the diversity of their candidates.12 The company’s Twitter and Facebook accounts reach thousands of talented candidates across the globe via targeted messaging and a universal company platform accessible in dozens of languages.13

School districts’ application and selection processes often emphasize static application materials over performance-based measures

Across all industries, selecting well-suited, high-quality candidates is critically important for minimizing turnover and, by doing so, the costs of recruitment and hiring.14 While a teaching candidate’s certification, education, and experience are one way to assess his or her qualifications, research provides mixed evidence on whether these things correlate with a teacher’s performance in the classroom.15 Including performance-based tasks during the hiring process—by, for example, requiring candidates to perform a sample lesson or submit a video of a previous lesson—allows administrators to assess teaching style, management techniques, and cultural fit.16 Unfortunately, CAP’s survey found that many school districts hire candidates without first seeing them in action.

Fast facts: School districts’ application and selection processes

- More than 90 percent of districts require a written or online application, a resume, a proof of certification, and a reference. Yet only 13 percent of districts require a demonstration or a sample performance lesson with students to evaluate teacher candidates.

- Only 6 percent of districts require a portfolio or a demonstration/sample performance lesson with adults.

- More than one in three districts do not include an interview with the hiring principal as part of the hiring process.

Most successful companies recognize the importance of each hiring decision and consider more than education, experience, and certifications when evaluating candidates’ fit. They assess prospective hires’ skills in tasks and situations that they are expected to encounter in the role for which they are applying. Clothing company Old Navy, for example, uses a holistic set of criteria when vetting all job candidates. The company employs a multistep interview process, including group interviews and unorthodox questions, that looks beyond GPA and past experience to assess creativity, drive, and problem solving.17 This kind of application system contributes to the company’s diversity. Across all Gap Inc. companies, including Old Navy, women make up 74 percent of the employee population while 49 percent of all its U.S. employees identify themselves as ethnically diverse.18 Old Navy’s emphasis on performance-based metrics during its selection process ensures a strong cultural fit between the company and all hired candidates, and contributes to the recruitment and retention of its diverse employee pool.

School districts do not provide new teachers with substantive mentoring or onboarding opportunities to build new skills critical to their roles

In most careers, professionals gradually gain increased autonomy over a number of years, learning from more experienced employees and progressively demonstrating their capacity to take on more significant tasks. Employees are not expected to complete the same job on day one as they are after five years of experience. New teachers need the same opportunity to refine their skills and assume greater responsibilities as they gain experience. Beginning teachers need to learn new skills from master teachers, practice those skills, adjust their teaching methods based on actionable feedback, and gradually assume increased responsibility in the classroom and at the school level. Our human capital systems survey found that, while many school districts offer induction programs, they often fail to provide new teachers with enough opportunities to build their skills gradually and assume increased responsibility.

Fast facts: School districts’ mentoring and onboarding opportunities

- Almost 20 percent of districts do not provide even the most basic formal district-sponsored induction program for beginning teachers.

- Among districts that do provide new teachers with a district-sponsored formal induction program:

- Only 14 percent of districts provide beginning teachers classroom assistance, such as teacher aides.

- Only 14 percent of districts provide beginning teachers with a residency year during which teachers can practice their skills before leading a classroom of their own.

- Only 6 percent of districts provide beginning teachers with a reduced teaching load.

- Only 3 percent of districts have all beginning teachers co-teach.

- Only half of districts allow beginning teachers to attend regularly scheduled meetings with their principal.

- Among districts that do provide new teachers with instructional coaching:

- Only 7 percent of districts provide new teachers with instructional coaching once a week.

- Only 18 percent of districts provide new teachers with instructional coaching twice a month.

In contrast, companies committed to developing their employees’ talent often provide new employees with an immersive onboarding experience that gives new hires the opportunity to ask questions, learn important components of workplace culture, develop relationships with colleagues, and gradually build their skills on the job. Some companies also use data to better understand retention and workplace engagement discrepancies so that they can mitigate attrition through induction programs, especially among employees of color.19

For example, Sodexo, a hospitality company that provides food services in 80 countries, instituted the Spirit of Mentoring program in 2004 with the aim of “establishing a diverse pipeline, developing leaders, aligning resources and strategies, driving organizational culture, and cutting costs.”20 Over the course of a year, Sodexo trains and monitors the progress of mentors and mentees, who meet monthly.21 A survey of participants found that for every dollar spent on the mentoring program, there was $2.28 realized in retention and increased productivity.22 A similar study also found that 72 percent of mentees and 79 percent of mentors cited increased job satisfaction as a benefit of the mentoring program, while 72 percent of mentees and 74 percent of mentors cited increased organizational commitment.23

In the early 2000s, IBM created its own Assimilation Process, through which each new employee spends his or her first two years on the job developing new skills, exploring his or her interests within the company, receiving coaching, and integrating into IBM’s workplace culture.24 Every new hire at IBM has access to both the company’s global employee network and a Project Management Center of Excellence, which offers courses related to each employee’s chosen skill set.

School districts do not provide teachers with enough opportunities for professional development or access to professional learning systems that support teachers’ continuous growth

Multiple studies have demonstrated that organizations that prioritize a performance-management system that supports employees’ professional growth outperform organizations that do not.25 Similar to all professionals, teachers need feedback and opportunities to develop and refine their practices.26 As their expertise increases, excellent teachers want to take on additional responsibilities and assume leadership roles within their schools.27 Unfortunately, few educators currently receive these kinds of opportunities for professional learning and growth.28 For example, well-developed, sustained professional learning communities, or PLCs, can serve as powerful levers to improve teaching practice and increase student achievement.29 When implemented poorly, however, PLCs result in little to no positive change in school performance.30

Our survey found that school districts often fail to provide frequent professional development opportunities that can help teachers learn new techniques and become more effective in their classrooms. Likewise, many districts do not provide teachers with professional learning systems that support their continuous growth.

Fast facts: School districts’ professional learning systems

- More than half of districts do not provide or offer teachers coursework to improve their teaching.

- One-quarter of districts do not provide or offer teachers the opportunity to participate in professional learning communities, in which groups of educators work collaboratively to improve their teaching skills.

- More than 40 percent of districts do not provide or offer teachers the opportunity to participate in lesson study or study groups with other teachers.

- When responding to teacher evaluations, more than one-quarter of districts do not provide teachers with additional opportunities for professional development.

According to a 2016 Gallup poll, Millennials rate the opportunity to “learn and grow” as an extremely important aspect of jobs to which they might consider applying.31 Eighty-seven percent of Millennials said that “development” was an important part of a job.32 Unlike many school districts, various entities elsewhere in the public sector and in the private sector have responded to their interests and are increasing the amount of feedback, professional development opportunities, and support they provide to employees.33

The U.S. military, for example, has developed a wide range of professional growth opportunities to help recruit and retain highly skilled individuals.34 Members of the military can access a broad array of professional development options, such as advanced education and technical training; opportunities to meet with senior leadership; and chances to participate in leadership development forums.35 Similarly, the American Heart Association launched the American Heart University in 2008. The university provides employees with 150 online, job-related courses on topics that include advocacy, health care, fundraising, and technology.36

School districts do not compensate teachers similarly to college-educated professionals in other fields or provide teachers with the resources they need to do their jobs well

A recent study showed that high-achieving undergraduates rank “salary for those established in the career” as one of the four most important factors when considering a future career.37 Many high-performing organizations prioritize competitive compensation packages to attract qualified employees. Unfortunately, teacher compensation has not kept pace with increases in salaries in other sectors.38 According to a 2016 nationally representative survey of more than 3,000 teachers, nearly half of teachers would leave teaching “as soon as possible” if they could find a higher-paying job.39 Furthermore, most teachers are not rewarded for working in hard-to-staff schools, in shortage areas, or for their excellence in the classroom. (see Appendix B) As a result, teachers who have opportunities in better paying fields are more likely to leave.40

Teachers’ low salaries are compounded by the fact that they frequently have to use their own money to pay for basic school supplies. According to a 2015 survey of 1,000 teachers, 91 percent of teachers used some of their own money to pay for school supplies, while 38 percent used only their money for school supplies.41 Respondents expected to spend an average of about $500 on school supplies during the school year.42 These survey results indicate that many school districts fail to provide teachers with the instructional and classroom resources they need to do their jobs.

CAP’s human capital systems survey reinforced these findings.

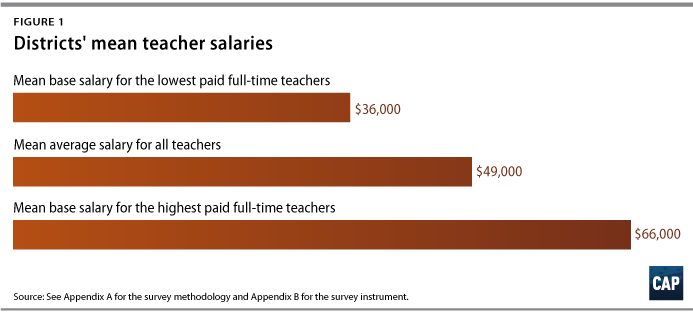

Fast facts: School districts’ compensation structures

- The mean average salary for a teacher in all districts was just under $49,000.

- The mean base salary for the lowest paid full-time teachers in districts was approximately $36,000.

- The mean base salary for the highest paid full-time teachers in districts was approximately $66,000.

- Nearly two-thirds of districts are not able to offer pay incentives or differentiated pay to teachers—for example, cash bonuses, salary increases, or different steps on the salary schedule—to reward or recruit teachers.

- Three-quarters of districts do not use cash bonuses, salary increases, or different steps on the salary schedule to recruit or retain teachers to teach in high-need schools.

- 41 percent of districts do not use cash bonuses, salary increases, or different steps on the salary schedule to recruit or retain teachers to teach in fields with shortages.

- Just more than half of districts provide teachers with reimbursements for purchased classroom supplies.

In order to compete for top talent, many organizations carefully fine tune their compensation programs to keep up with competitors. Netflix, for example, uses base salaries that it believes will recruit candidates within a highly competitive business environment. Due to Netflix’s rapid growth over the past decade, the company had to strategically adapt its human capital policies to increase its workforce. Netflix now offers higher market-based pay compared with its competitors rather than the annual bonuses typical of many private-sector organizations.43

In instances when smaller organizations or nonprofits cannot compete with large or private sector organizations, many organizations offer unique benefits—such as comprehensive medical insurance plans, flexible schedules, or financial planning services—to entice employees.44 Alpert Jewish Family and Children’s Service, or AJFCS, a nationally accredited social services agency in Palm Beach, Florida, uses innovative benefits to recruit and retain talent—especially workers in the later stages of their careers. AJFCS allows employees to customize their work schedules to fit their needs. In addition, the organization offers a competitive benefits package, part of which includes a formal training program for staff and reimbursement for tuition paid toward advanced degrees.45

School districts do not strategically recruit diverse candidates or create inclusive, supportive environments to retain them

The teachers leading American classrooms remain overwhelmingly homogenous. While diversity of all kinds—gender, religious, cultural, and racial—is beneficial for students and teachers alike, the lack of racial diversity among teachers is especially problematic.46 For example, students of color score slightly higher on standardized tests when taught by teachers of color, possibly because they tend to hold these students to higher expectations than other teachers do.47 Furthermore, racial diversity of teachers has a positive effect on all students, helping break down biases across races.48 Yet while the majority of students enrolled in public schools are students of color, only 18 percent of the teacher workforce identifies as people of color.49

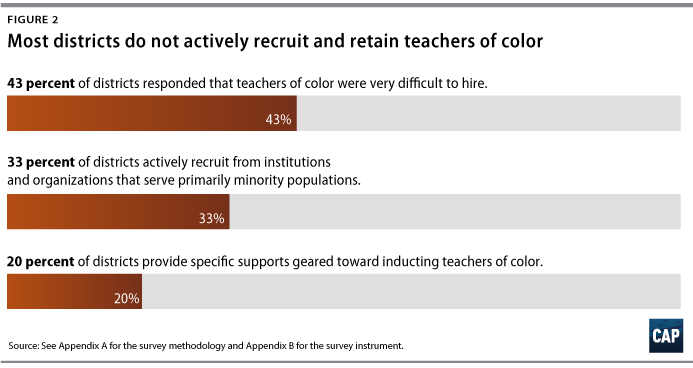

Our survey found that while school districts report that it is difficult to attract and retain teachers of color, many are not yet implementing strategies to address these challenges.50

Fast facts: School districts’ recruitment and retention of diverse candidates

- On average, 90 percent of teachers in each surveyed district identified as white, non-Hispanic.

- Forty-three percent of districts responded that teachers of color were “very difficult” to hire, more so than special education teachers, teachers of English Language Learners, and high school science teachers.

- Only one in three districts actively recruits from institutions and organizations that serve primarily minority populations.51

- Forty percent of districts consider “contribution to workforce diversity” minimally or not at all when hiring teachers.

- Eighty percent of districts do not provide any specific supports geared toward inducting teachers of color.

- Among districts that recruit from institutions and organizations that serve primarily minority populations:

- Fifty-six percent of districts post job openings on websites targeting primarily minority populations.

- Twenty-four percent of districts advertise job openings in publications targeting primarily minority populations.

Many companies have revised their human capital systems to recruit a more diverse talent pool and create a more inclusive work environment. For example, traditional recruitment strategies that rely on informal networks for recruitment often lead to an overwhelmingly homogeneous workforce. Individuals are more likely to recruit those with experiences and backgrounds similar to their own.52 To counter this, some businesses now hold recruiting events at historically black colleges and universities, such as Howard University, to diversify their applicant pools.53 These events allow companies to be more selective among a larger, more diverse group of candidates.

The American Heart Association, or AHA, recognizes that a diverse workforce is central to its business plan and has improved its recruitment and professional development strategies to recruit and retain employees of all backgrounds and perspectives.54 The AHA invests in a diversity recruiting specialist who builds and maintains relationships with various organizations to identify exemplar diverse candidates.55 In addition, the AHA employs a diversity and inclusion manager who designs cultural awareness learning opportunities throughout the year.56

Some institutions of higher education have also pledged to increase the diversity of their workforces by recruiting, supporting, and retaining more faculty members of color. In 2015, Columbia University announced a $33 million commitment to improve faculty diversity, including through funding grants to support junior faculty research and creating various programs to provide mentoring and support to new faculty members.57 In addition to better supporting faculty of color, Columbia’s initiative also seeks to expand the university’s pool of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer, or LGBTQ, faculty members.58

These kinds of efforts are not exclusive to Columbia. In 2015, Yale University created a new position—deputy provost for faculty development and diversity—dedicated solely to diversifying the faculty.59 In 2014, Brown University’s president announced a goal to double the percentage of the university’s faculty of color by 2024.60 By promoting programs that provide faculty of color with mentoring supports, these universities seek to create and sustain diverse faculty cohorts.

Policy recommendations

Currently, school districts struggle to attract talented professionals into teaching, especially as they are often heavily recruited for more lucrative opportunities outside the classroom. In order to develop a strong teacher pipeline—similar to talent pipelines developed by some of the country’s most successful organizations—school districts should adapt their recruitment and retention strategies and adopt the best practices of high-performing organizations. CAP has developed the following recommendations for school districts to strengthen their human capital systems:

- School districts should devote more time and resources to intentional recruitment. School districts should develop thoughtful recruitment strategies to strengthen their talent pipelines, including by approaching talented candidates individually. In addition to standard measures—such as posting job openings online and recruiting at local universities—school districts should leverage technology and personal networks to attract talent from near and far. Social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, provide additional avenues to connect with possible candidates. School districts should also ensure that they have ample staff to develop and implement innovative recruitment practices, especially to address priorities based on areas with teacher shortages.

- School districts should include performance measures in their application and selection processes. School districts should ensure that all potential hires undergo a multistep selection process that allows school districts and schools to assess each candidate’s teaching ability, presence in the classroom, and overall cultural fit. The selection process should include performance measures, including model lessons, and present candidates with real-life teaching scenarios in order to understand and evaluate each candidate’s decision-making skills when leading a classroom. Districts should also include diverse perspectives—both in terms of race and ethnicity and in terms of job position—on the hiring committee and invite teachers to join school leaders and district representatives when interviewing candidates. By doing so, candidates will learn about the culture of the school and teachers will have a voice in selecting their school’s instructional team.

- School districts should provide new teachers with opportunities to build their skills and gradually assume increased responsibility. School districts should provide new teachers with more intensive induction experiences that allow them to practice their skills and orient themselves within the larger school environment. As a requirement of their preparation, teachers should participate in a multiyear onboarding process that allows them to gradually assume increased responsibility and practice essential teaching skills. Teachers should continue to receive coaching from an accomplished mentor teacher as part of an intensive induction experience that provides new teachers with valuable feedback, fosters continual growth, and allows teachers to demonstrate progress and assume additional responsibilities in the classroom and at the school level. These experiences ensure that new teachers understand their school’s professional expectations; receive critical guidance and feedback from more experienced, accomplished teachers; and build their skills over time, as they would in other professions.

- School districts should offer teachers opportunities and time to grow, as well as implement professional learning systems that support teachers’ continuous growth. School districts should create avenues and mechanisms for teachers to improve as educators and assume additional responsibilities. To do so, school districts should prioritize professional development opportunities by ensuring that high-quality skill-development opportunities are available to all teachers and by providing teachers meaningful feedback on their practices. School districts should also ensure that teachers have the time and resources to access a system of continuous professional learning that provides them with actionable recommendations to improve areas of needed growth. Similarly, districts should provide professional learning that responds to teachers’ specific needs, rather than generalizing it for all teachers. Additionally, school districts should create career pathways for teachers as they gain experience, allowing these educators to serve as valuable teacher leaders and mentors to their less experienced colleagues.

- School districts should ensure that teachers’ compensation is similar to that of other professions requiring the same level of education and provide teachers with necessary teaching resources. School districts should increase teachers’ compensation so that starting and midcareer teachers’ salaries are in line with similarly educated peers in other professions. School districts should also shorten the timeline for teachers to achieve maximum salaries. Additionally, school districts should provide teachers with increased compensation for assuming leadership roles and acquiring new skills, thus creating opportunities for teachers to grow professionally without leaving the classroom. School districts should also compensate teachers more for working in hard-to-staff schools and subjects, including science, math, and special education, especially as these teachers often have more profitable opportunities outside of the teaching profession due to their expertise.61 To increase overall take home pay, school districts should provide adequate funding for school resources, ensuring that teachers do not have to purchase necessary school supplies out of their own pockets.

- School districts should prioritize teacher diversity and develop strategies to attract and retain teacher candidates of color. School districts should focus more of their recruitment efforts on identifying high-achieving, diverse candidates, especially through institutions that serve people of color, so that the teacher workforce better reflects the United States’ increasingly diverse student population. Once hired, school districts should develop induction and mentoring programs to ensure that teachers of color receive the supports they need to remain in the profession and offer professional development opportunities for all staff to cultivate an inclusive working environment.

While companies across the country have made efforts to modernize how they recruit, train, and pay their employees, these changes have not yet become widespread in the teaching profession. As a result, teaching has become a relatively less attractive choice for talented professionals. In order to attract and retain the excellent teachers that students in this country deserve, school districts must adopt human capital best practices used to attract talent, increase productivity, and improve outcomes within high-performing organizations.

Conclusion

In his bestselling book, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…and Others Don’t, author Jim Collins argues that “great vision without great people is irrelevant.”62 In other words, talent management and human capital systems are crucial parts of building a successful business. Great teachers play a similarly important role in the success and performance of schools. More and more research is available that demonstrates the impact that great teaching has on students and schools, but school districts will not be able to attract and retain these teachers unless they modernize their human capital systems. Doing so could improve both the efficiency and effectiveness of schools, with benefits for teachers and students alike.

Appendix A: Methodology

The survey was developed, administered, and analyzed with support from Policy Studies Associates, or PSA, CAP’s contractor for this project.

Survey sample

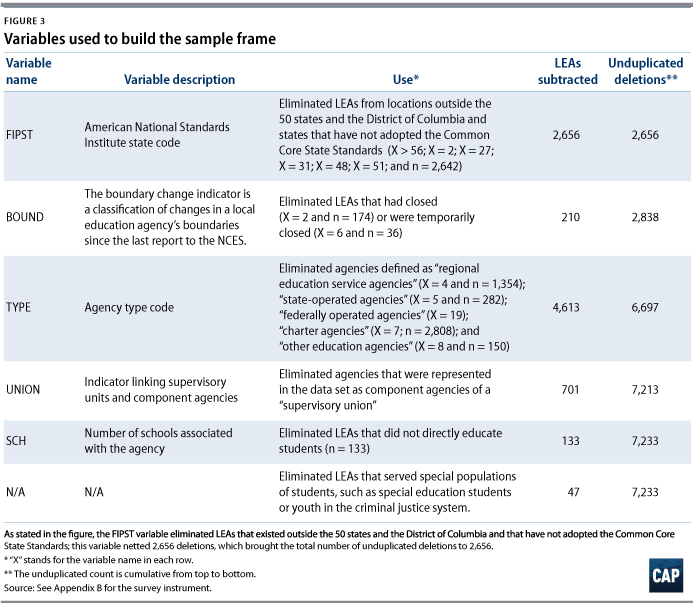

PSA used the 2012-13 Common Core of Data Local Education Agency Universe Survey conducted by the National Center of Education Statistics, or NCES, to develop the sampling frame, or the school districts selected to participate in the survey.63 This publicly available dataset contains information on 18,968 elementary and secondary education agencies located in the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia; Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands; the Department of Defense schools; and the Bureau of Indian Education.

From the dataset of 18,968 education agencies, 7,233 agencies were removed that did not match the study population criteria, for a total of 11,735 districts in the sample frame. In addition, the agencies located outside the 50 states and the District of Columbia were removed from the sampling frame, as were agencies that were not in operation; that were temporarily closed; or that were regional education service agencies, federally and state-operated agencies, charter agencies, or designated as “other education agencies.”

The dataset also included agencies that were component(s) of a supervisory union, sharing a superintendent and administrative services with other local school districts. In these cases, the agency defined as the “supervisory union” was retained, but component agencies associated with the unions were removed. Also removed from the sampling frame were local education agencies, or LEAs, that did not directly educate students through the employment of teachers and the operation of school buildings; many of these agencies represented towns that sent their students to neighboring districts or cooperative districts. Finally, agencies that solely served specific segments of the population, such as vocational centers or schools for special education students, were removed. Figure 3 summarizes the deletions made to the dataset to arrive at the final sample frame.

The final sample includes a nationally representative sample of 200 public school districts.

Survey development

The purpose of the survey was to understand district successes and challenges with respect to teacher recruitment, selection, compensation, induction, evaluation, and support. As part of survey development, PSA sent a draft of the instrument to human resource directors or superintendents in 32 LEAs and asked them to review it and provide feedback on the appropriateness and clarity of the wording and on the focus of the survey questions. PSA drew the sample randomly by assigning a random number to each district. It then sorted the districts, using the first 32 for the pilot sample and the remaining 200 for the full survey. The LEAs were also asked to estimate the amount of time they would need to complete the survey and to indicate who else in their district might be involved in responding to individual items on the final survey. The final version of the survey reflects the feedback that PSA received from the 12 districts that agreed to participate in the pilot. Because the final survey did not change significantly from the draft survey, PSA did not administer the survey a second time to the original 32 LEAs.

Survey administration

In late September 2015, CAP mailed a letter to human resource managers and/or district superintendents of the sampled districts to describe the study purposes and to invite their participation. Within one week, PSA emailed each respondent inviting them to participate in the survey and directing them to click on the personalized link embedded in the email to begin the online survey. PSA sent reminder emails once a week for three weeks and then followed up by phone with all non-respondents. Finally, toward the end of the survey administration period, CAP mailed a hard copy version of the survey—including a self-addressed, stamped envelope—to all nonrespondents and asked that they return the survey to PSA as soon as possible.

As an incentive, all respondents received a $50 gift card for submitting their completed surveys.

Districts returned surveys between October and November 2015. PSA received completed responses from 108 of the 200 districts, 7 partial responses, and 11 refusals in the sample; this corresponds to a response rate of 63 percent.

To read the complete survey, please see the PDF of this report.

About the authors

Annette Konoske-Graf is a Policy Analyst with the K-12 Education team at the Center for American Progress. After studying political science and Spanish literature at the University of California, Berkeley, she moved to Miami, Florida, where she taught ninth and 10th grade literature in Little Haiti. She was one of seven district finalists and runner-up for the 2012 Francisco R. Walker Rookie Teacher of the Year Award and the winner from the Education Transformation Office Region of Miami-Dade County. The Education Transformation Office serves the 27 high-needs schools within the district. Konoske-Graf graduated from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in May 2014 and from Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs, or SIPA, in May 2015. Upon graduation from SIPA, she won the Raphael Smith Memorial Prize for her essay on a taxi ride in southern Chile.

Lisette Partelow is the Director of Teacher Policy at the Center. Her previous experience includes teaching first grade in Washington, D.C.; working as a senior legislative assistant for Rep. Dave Loebsack (D-IA); and working as a legislative associate at the Alliance for Excellent Education. She has also worked at the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Education and Labor and the American Institutes for Research.

Partelow has a master’s degree in public affairs from Princeton University and a master’s degree in elementary education from George Mason University. She received a bachelor’s degree from Connecticut College.

Meg Benner is a Senior Consultant to the Center. Previously, she was a senior director at Leadership for Educational Equity. Benner worked on Capitol Hill as an education policy advisor for the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, where she advised Ranking Member George Miller (D-CA) and served as a legislative assistant for Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) and Sen. Christopher Dodd (D-CT). She received her undergraduate degree in American studies from Georgetown University and a master’s degree of science in teaching from Pace University.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge several people who contributed to this report. Policy Studies Associates, or PSA, provided invaluable help developing, administering, and conducting the survey. We are especially grateful for the extensive and valuable support from Leslie Anderson at PSA. We also wish to acknowledge Alexander Sileo, who provided helpful research.