The past four years have swept away the old pillars of U.S. policy toward the Eastern Mediterranean. Egypt, a traditional American security partner, is confronting a staggering political and economic crisis. Syria has descended into a horrific civil war with no resolution in sight. Lebanon is clinging to basic stability in the face of long-standing sectarian tensions and a massive refugee crisis. Jordan remains a strong U.S. ally but faces structural threats that stem from demographic trends and the war in Syria. Iraq is once again engulfed in a struggle against militancy stoked, in part, by perceptions that Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and his supporters have institutionalized their ascendancy in a way unacceptable to Iraq’s minorities. Of course, governments across the region are struggling to confront the rising influence of violent Salafi jihadists. The seizure of Mosul—Iraq’s second-largest city and home to nearly 2 million people—by the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, or ISIS, brought this reality into stark relief.

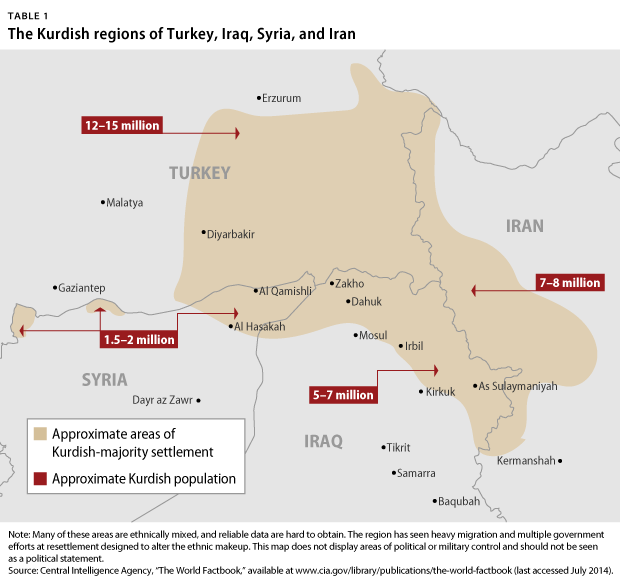

In this context, the potential ramifications of recent developments in Turkey and along its borders have become critical to U.S. interests and the long-term trajectory of the Middle East as a whole. Political and military Kurdish actors have, separately, solidified an autonomous government in northern Iraq and carved out a semi-independent stronghold in northern Syria. Indeed, Kurdish forces in northern Iraq and, to a lesser extent, northern Syria have become a bulwark against jihadi groups such as ISIS and a bastion of stability in a region fracturing along sectarian lines. This reality necessitates a re-evaluation of U.S. policy toward Kurdish political groups and a reinvigoration of Turkey’s peace process with its own Kurdish minority.

A key NATO ally and a model of economic and political stability for many years, Turkey is in the throes of a deep political crisis that is distracting from its efforts to achieve a lasting peace settlement with its Kurdish minority, as well as mitigate the spillover effects of the Syrian conflict and counter the rise of violent groups in Iraq. After promising first steps, the peace process seems to be stuck, with Kurdish insurgents halting their withdrawal from Turkey due to the Turkish government’s failure to quickly provide more extensive political and language rights to Kurdish communities. But both the Turkish government and its Kurdish counterparts have come too far to back away; the political cost of a breakdown in negotiations may be prohibitive to both sides given the turmoil on Turkey’s borders and the threat of ISIS to Kurdish enclaves in Syria and Iraq.

For the United States and Turkey, the rapidly changing political situation in Syria and Iraq underpins the need for new partners with whom to work toward regional stability and the provision of basic governance. This goal reaches beyond a narrow—albeit important—notion of national security, rooted in combating militancy and denying terrorist organizations space in which to operate. The effort should also be informed by the wider objective of allowing the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean to make political reforms and grow their economies—a goal that is crucial to peacefully accommodating the demographic wave reaching maturity this decade within pluralistic and accountable political institutions. The realities on the ground mean that this search for partners must include engagement with Kurdish political actors to encourage peaceful relations with their respective host countries, thus promoting regional stability and advancing U.S. interests.

This peacebuilding process will take time, requiring long-term efforts to make and cultivate new contacts. Meanwhile, given the complexity and fluidity of current events in the region, the United States and its allies cannot afford to be picky in their search for governance partners. The Syrian conflict has made it necessary for the United States to deal with Kurdish organizations that are helping define the reality on the ground, such as the militant Democratic Union Party, or PYD, with which the United States does not have relations.

Additionally, given Iraq’s fractured politics and the pressing security situation in the north of the country, the United States must set aside the concerns of Prime Minister al-Maliki and redouble its outreach to President Massoud Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party, or KDP, to bring it into a productive peacebuilding role. Indeed, this process finally began in earnest with U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry’s visit to Erbil in June and Vice President Joe Biden’s “drop-by” with representatives of the Iraqi Kurdistan Regional Government, or KRG, at the White House in July.

Solving many of the region’s major problems will require Kurdish participation and consultation. Kurdish organizations have the potential to be constructive partners in providing stability in both Iraq and Syria. Given the pluralistic, secular rhetoric of many of these groups, the United States should re-evaluate its current policies, which have largely bowed to the traditional Turkish strategy of decreasing Kurdish organizational capacities and shied away from engagement with the KRG for fear of undermining Iraqi national unity. With Iraq fractured, and with Turkey increasingly relying on Kurdish forces as a buffer to instability along its borders, these concerns about maintaining the writ of Baghdad are becoming less important.

This analysis does not represent advocacy for Kurdish nationalism or independence, but rather acknowledges the realities on the ground. In northern Iraq, the KRG—a largely autonomous Kurdish-dominated administrative body—has demonstrated reasonably effective governance and economic growth. Most recently, following the collapse of the Iraqi Army’s presence in Mosul and other parts of northern Iraq, Kurdish forces, known as the Peshmerga, took control of Kirkuk, a major city and oil hub roughly 150 miles north of Baghdad. In northeastern Syria, a newly autonomous Kurdish-controlled region—sometimes called Rojava—has formed amid the turmoil of the civil war. Syrian Kurdish forces have also battled with radical Islamist militants, including ISIS, and occasionally fought alongside the Free Syrian Army as part of their efforts to protect local populations and maintain basic stability.

In Turkey, the state’s long-standing efforts to assimilate Kurdish culture and suppress Kurdish political organizations—primarily the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, which is also a militant armed group—through military force seem to have been abandoned. The Turkish government has undertaken a new set of political negotiations, accompanied by a softer rhetoric toward cultural differences. Turkey’s approach toward the Kurds remains integral to the country’s process of democratization and the establishment of the effective rule of law, which is in turn important to Turkey’s role as a NATO ally and U.S. partner. It is in this longer-term context—alongside the urgent need to insulate against the further spread of violent groups such as ISIS—that the Kurdish question should be re-examined.

Of course, the Kurds are not a coherent political group. Personal rivalries, national identifications, borders, economic interests, and political beliefs are differentiating factors. But there are signs of a mutual cohering of the political agenda across much of the Kurdish-majority region, driven in part by the rise of Kurdish-language media and growing linguistic convergence. Regarding the Kurds as a loosely confederated group of political actors sharing a language, history of oppression, and—in some cases—aspirations for political autonomy, a number of questions arise:

- What is a realistic role for Kurdish political organizations in the new Middle East?

- What are the various goals of these groups, and can they be accommodated within a stable regional model?

- What is expected of these groups, and what should be offered in return?

- How should the United States and its NATO allies—including Turkey—interact with these subnational groups and political organizations?

The Kurds’ place in the Middle East is not a new question. Neither, more broadly, is the question of how to incorporate subnational ethnic or religious groups within the national borders that emerged from World War I. By and large, most policymakers have concluded that it would be costlier to redraw those borders than to work within existing lines, problematic as they often are. The national identifications based on these boundaries have taken root over the past century and should not be underestimated. This report does not dispute that core conclusion, nor does it advocate a de facto Kurdish nation-state. But the reality of two autonomous Kurdish regions and a third engaged in negotiations with its national government over greater self-determination—along with the effective collapse of central government authority in both Syria and Iraq—demands a re-examination of this question. Western policy circles should devote greater thought to the problem and undertake more frequent and nuanced outreach to Kurdish political actors.

This report seeks to advance this policy conversation by outlining the political context in Turkey; summarizing the relevant history of the Kurdish regions; examining the current state of the peace process in Turkey; placing the issue in its regional context, particularly with regard to evolving autonomy in Syrian and Iraqi Kurdish areas in light of the rise of ISIS and the collapse of state authority; explaining the potential consequences of positive or negative outcomes with the Kurds; and evaluating U.S. policy in light of these challenges.

Michael Werz is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress. Max Hoffman is a Policy Analyst at the Center.