Introduction and summary

The rapid and ongoing decline of nature in the United States poses a threat to the health, well-being, and prosperity of every community in the country. The disappearance of natural areas—which occurs at a rate of a football field every 30 seconds—imperils clean air and drinking water supplies.1 Open lands and healthy waters where families play, fish, hunt, and unwind together are growing increasingly scarce. And habitat destruction and climate change are fueling an extinction crisis and increasing the frequency at which dangerous pathogens cross over into human communities.

The problem of nature loss is particularly acute on private lands in the United States. Urban sprawl, oil and gas extraction, and other industrial uses consumed more than 45,000 square miles of farms, ranches, and private working forests in a recent two-decade span.2 Overall, more than 75 percent of the natural areas lost to development from 2001 to 2017 in the United States were on privately owned lands.3

Family farmers, ranchers, and forest owners, however, have been a bulwark against the decline of nature on private lands. All across the country, private landowners are going out of their way to protect wildlife habitat, save wetlands, and pass their lands down to their children in a healthy and productive condition.

The coronavirus-induced economic collapse, however, will likely deal a catastrophic blow to families who make their living off their lands. Restaurant closures, shutdowns at meatpacking plants, and falling exports of agricultural goods have left farmers and ranchers with fewer places to sell their products and sharply reduced revenues. Economists have already documented a roughly 25 percent increase in farm bankruptcies since 2019, and bankruptcies will likely continue to rise sharply in the months ahead.4 Unless policymakers can provide relief where it is needed most, family farmers, ranchers, and private forest owners will be forced to sell off their lands and operations. The economic damage of losing these operations will ripple out to feed supply stores, hardware stores, equipment dealers, and other rural businesses that support working landowners. Meanwhile, as families are forced to sell their working lands, the United States will see even more of its privately owned natural areas subdivided for suburban sprawl, sold off for industrial agriculture, or sacrificed for drilling and mining.

U.S. policymakers need to act quickly and decisively to help family farmers, ranchers, and forest owners keep their lands—and keep them healthy—through this catastrophic pandemic and economic crisis. Specifically, the federal government should immediately expand and accelerate the nation’s private land conservation easement programs. Doing so will give farmers, ranchers, and private landowners the option to transform a portion of a traditionally illiquid asset—the development rights to their land—into much-needed cash revenue that can help them weather this economic storm.

This intervention on behalf of working landowners would not only help rescue rural economies but also be one of the most ambitious nature conservation and climate change solutions the United States has ever undertaken. This 10-year national effort, which we propose be called the “Race for Nature,” would lead to a tenfold increase in the pace of private land conservation in the country and, ultimately, the permanent or long-term protection of at least 55 million acres of natural places and the sequestration of at least 70 million metric tons of carbon by 2030. The Race for Nature would enable the United States to take a giant step forward toward a national “30×30” objective of protecting at least 30 percent of all lands and ocean by 2030—a goal that scientists say is necessary to achieve in order to protect clean drinking water supplies, clean air, and abundant food supplies.

Rescue and recovery: A two-phased approach

The Center for American Progress recommends that Congress launch the Race for Nature in two phases: a rescue phase and a recovery phase.

In the immediate rescue phase of the Race for Nature, to be implemented by the end of September 2020, the agriculture and appropriations committees in the Senate and House should draft and pass legislation that increases funding for existing conservation easement programs, helps landowners gain access to easements more quickly, and pilots new emergency conservation easement programs.

In the second phase of the Race for Nature—the recovery phase—Congress should draw on lessons learned in the rescue phase to enact, through the 2023 Farm Bill and other legislation, a long-term expansion and improvement to the nation’s conservation easement programs. In this second phase of the Race for Nature, Congress should codify reforms that further simplify and accelerate the pace of implementation of conservation easement programs; establish clear and ambitious goals for nature conservation and carbon sequestration; require federal agencies to develop a cohesive and science-based strategy for achieving these nature conservation and climate change goals; and provide sustained and robust funding to implement this national private land conservation strategy.

The mounting economic losses in America’s rural communities leave policymakers with little time to act if they wish to help family farmers, ranchers, and forest owners stay afloat. By honoring and renewing the United States’ remarkable private land conservation traditions through the Race for Nature, however, Congress can safeguard critical water, air, natural areas, and food supplies while helping rural communities endure this turbulent time.

The nature crisis on America’s private lands

This report is part of a series of publications that the Center for American Progress is releasing on the nature crisis in the United States and the strategies that policymakers and communities can adopt to accelerate the protection of the nation’s lands and ocean. The first two reports in the series—“How Much Nature Should America Keep” and “The Green Squeeze”—assess the condition of nature in America, analyze the factors that are driving its decline, and outline principles for how the nation could and should pursue a 30×30 goal.5

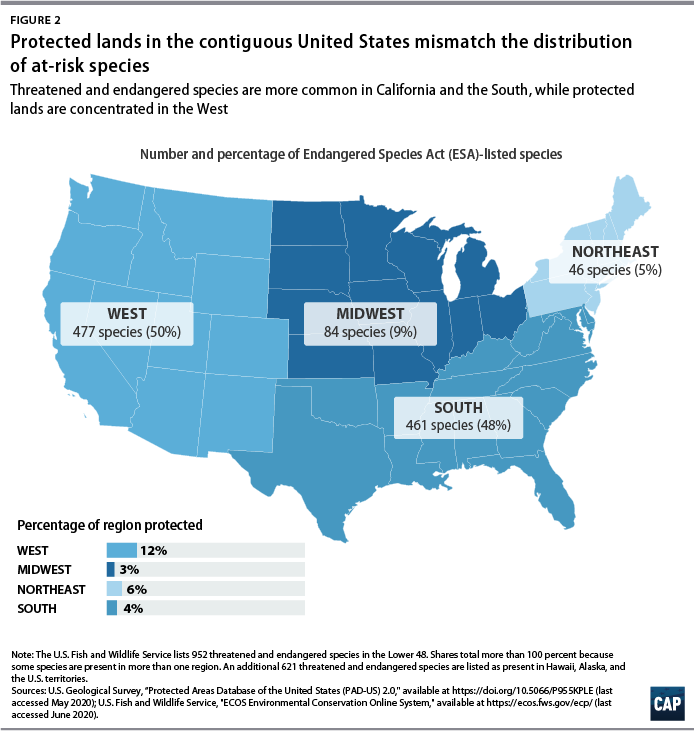

One critical finding of the first two reports in this series is that nature in the United States is declining most quickly on privately owned lands. According to an assessment of natural area loss in the contiguous 48 states, commissioned by the Center for American Progress and conducted by a team of scientists at the nonprofit organization Conservation Science Partners, natural areas are being lost almost five times faster on private lands than they are on lands that are owned and managed by federal or state agencies.6 Wildlife species that are listed under the Endangered Species Act are being hit hard by the rapid disappearance of nature on private lands; research has shown that the habitat of threatened and endangered species is disappearing more than twice as quickly on unprotected private lands than it is on all federal lands.7

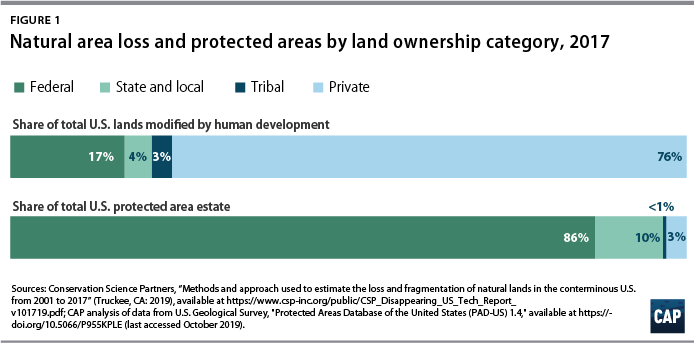

One reason why natural areas are disappearing most quickly on private lands should not be surprising: Only a small portion of the nation’s privately owned lands are protected from development. Overall, 12 percent of U.S. lands are permanently protected to retain their natural condition.8 The vast majority of this “protected area estate” is on nationally owned public lands— places that have been designated as national parks, wilderness areas, national monuments, national wildlife refuges, and other protected areas. (see Figure 1)

Only 3 percent of U.S. protected areas, however, are on private lands, notwithstanding the fact that 60 percent of all U.S. lands are privately owned. Outside of the American West, where large portions of lands are publicly owned, the sparsity of protected private lands presents a particularly grave threat to biodiversity and the provision of clean water, clean air, food, and other necessities that nature supplies. For example, in the Southeast and Midwest—the regions that experienced the most rapid disappearance of natural areas from 2001 to 2017—wildlife have relatively few protected lands, public or private, in which to find refuge. (see Figure 2)

Building on America’s private land conservation traditions

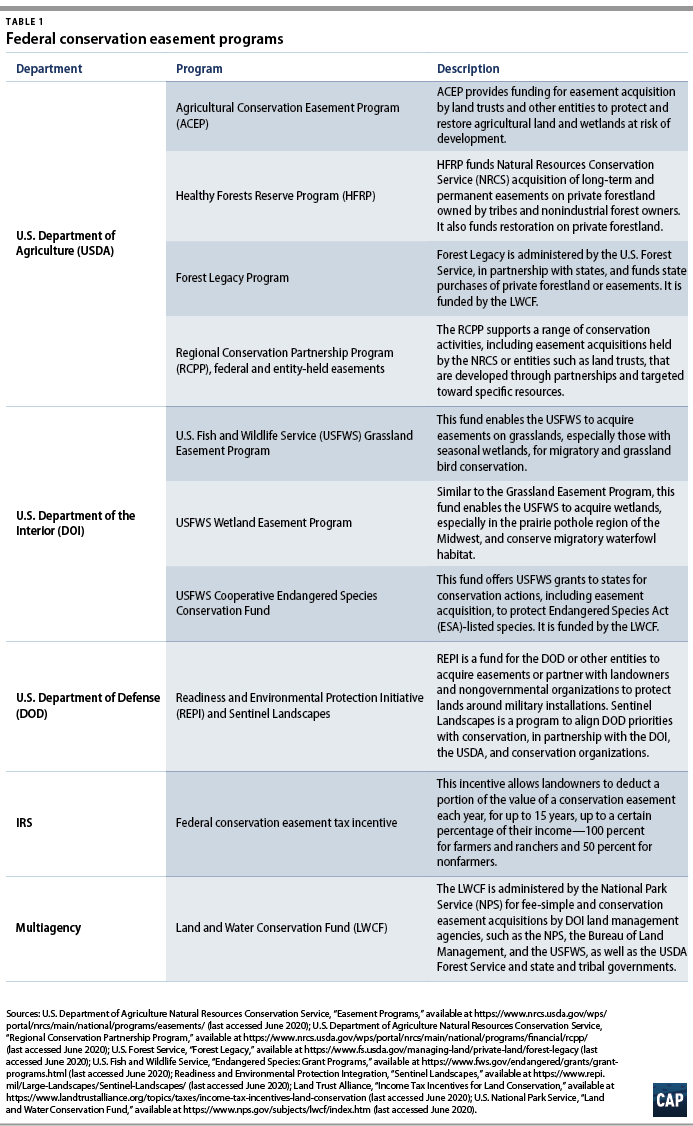

Although a small percentage of private lands are protected from development, many of America’s farmers, ranchers, and other private landowners have a long and proud history of conserving wildlife, cultivating the health of working forests, and restoring degraded lands. In the past 30 years, in particular, the set of tools and infrastructure available to support private land conservation has grown through new partnerships, national and state policy development, and locally led conservation initiatives.9 At the federal level, programs and funding sources have emerged across several departments to advance conservation. (see Table 1)

Land trusts, in particular, have emerged as an engine for conservation gains on private lands. These nonprofit organizations, of which there are now more than 1,000 across the United States, work with landowners in their communities to protect natural areas and open spaces while maintaining the economic productivity of working lands.10 The Land Trust Alliance, a national association of land trusts, estimates that their members have conserved between 1 and 2 million acres of land annually since 2006, funded by a combination of easement programs and tax incentives from federal and state agencies, as well as private philanthropy.11 Conservation easements have been especially important, as they allow landowners to transfer development rights on their property to a land trust or other entity to protect it, either permanently or for a set period of time. In return, landowners are often paid a percentage of the appraised property value while retaining title and, in many cases, continuing to use parts of the property for agriculture or other uses. Tax incentives, at both the federal and state level, also allow landowners to deduct the value of the easement from their income in certain situations.12

Time and time again, land trusts have proven that the conservation of private lands can provide a sustainable economic base for rural communities while preserving important traditions and ways of life. In 2019, for example, the Nature Conservancy announced the completion of the Cumberland Forest Project in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia.13 Through a series of acquisitions and partnerships, this project protected more than 250,000 acres of Appalachian forests that store carbon, provide clean drinking water, and protect a diversity of species. These lands, meanwhile, are continuing to support sustainable forestry work that provides jobs for local communities. In the West, land trusts have successfully pursued similar projects that, through easements on ranchland, protect habitat for the greater sage-grouse while preserving agricultural operations that anchor rural communities.14

Importantly, conservation easements have proven to be a valuable and effective tool for helping rural communities survive and recover from an economic recession. In the wake of the 2008 economic collapse, U.S. land trusts expanded their staff and volunteer capacity to help meet a surge in demand among landowners for the immediate financial benefits that conservation easements provide.15 After the housing bust slowed new development and depressed property values, California ranchers, Vermont farmers, and Montana forest owners were among the many U.S. landowners who turned to conservation as a strategy for preserving the economic viability of their operations and the quality of life of their communities.16

Conservation strategies must be scaled to the economic crisis at hand

Despite the remarkable economic and environmental benefits that the United States has gained through its current suite of conservation easement programs, existing policies and investments are not scaled for the gravity of the current economic crisis facing family farms, ranches, and private forest owners.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic, there were not enough financial resources available in federal conservation easement programs to meet the demand of landowners seeking to permanently protect their lands.17 U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) conservation programs, which are funded through the Farm Bill, are popular but perennially oversubscribed.18 For example, the Forest Legacy Program—which helps states and the U.S. Forest Service protect threatened forests—consistently receives far less money from Congress than what is needed to clear the backlog of easements that are agreed upon. The Agricultural Conservation Easement Program, a USDA program to protect croplands and wetlands that are vulnerable to development, is typically able to accept less than half of the easements that are submitted each year.19 Other federal conservation easement programs—including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s grassland and wetland easement programs, the U.S. Department of Defense’s Readiness and Environmental Protection Integration and Sentinel Landscapes programs, and the USDA’s Healthy Forests Reserve Program and Regional Conservation Partnership Program—are likewise plagued by inconsistent and inadequate congressional funding.

Bureaucratic complexities and slow implementation of projects also limit the effectiveness of current federal conservation easement programs. A landowner who is interested in participating in a federal conservation easement program must navigate an alphabet soup of agencies and programs, each with their own application protocols, priorities, and implementation standards. Even landowners who successfully complete the application process must sometimes wait years before the project is completed. For example, a group of four neighbors who wanted to conserve 600 acres of wetlands near the Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in New Mexico had to wait a decade to finally complete the project with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.20 More commonly, landowners can expect to wait three to five years for an easement project to be completed and funded.21 Most family farmers and ranchers cannot afford to wait that long, especially during an economic crisis.

Of course, not all conservation easements are implemented through direct federal or state purchases of easements. Many landowners receive financial benefits of implementing a conservation easement through tax policy; by donating a conservation easement to a land trust, for example, a landowner can deduct the value of an easement from their tax payments. The federal conservation easement tax incentive, in particular, has been widely used. The enhanced incentive, which passed in 2015, allows landowners to deduct a portion of the value of their easement from their taxable income each year for several years, with increased incentives for farmers and ranchers.22 This has made easements more accessible in places where family farmers and ranchers are struggling to make ends meet, instead of just locales with higher property values and landowner incomes.

Although these tax incentives have been a valuable tool for many landowners, some practices have emerged that favor wealthy investors adept at finding loopholes in tax structures. Known as syndications, these are groups of organized investors who acquire properties and use inflated appraisals for easements to collect outsized tax deductions. This financial opportunism has become more common in recent years, with the IRS estimating that it represented approximately $27 billion in claimed deductions from 2010 to 2017.23 Closing this loophole, and restoring the conservation intent of the tax incentive, should be a high priority for policymakers.

Despite needing some improvements, however, existing federal conservation easement programs and tax incentives provide a solid foundation from which to deliver a strong and swift response to the economic crisis facing family farmers, ranchers, and private forest owners and to build a more ambitious private land conservation agenda for the decade ahead.

The Race for Nature

To help family farmers, ranchers, and private landowners survive the economic downturn and keep their lands in a natural and healthy condition for future generations, Congress should immediately launch the Race for Nature to dramatically increase the pace of conservation on private lands.

The 10-year national initiative would increase funding for existing conservation easement programs, accelerate the disbursement of funds to deliver immediate help to at-risk landowners, develop and test new and simplified federal easement programs and strategies, and establish a long-overdue national strategy for maximizing the ecological and climate benefits of protecting private lands.

Given the scale and urgency of the challenges facing family farmers, ranchers, and private forest owners, congressional leaders should launch the Race for Nature in two phases: a rescue phase and a recovery phase.

Phase 1: Providing relief to help landowners weather the immediate economic storm

Unless Congress makes immediate additional investments and forces federal agencies to accelerate pending conservation projects, easement programs will likely be overwhelmed by demand in the months ahead. Families that want to generate immediate revenue by selling a conservation easement will be turned away, resulting in family farms, ranches, and private forests being sold off to an uncertain fate.

To confront this problem and deliver relief where it is most needed, congressional leaders should:

- Immediately: Announce the launch of the Race for Nature and state a clear commitment to delivering the resources needed to help family farmers, ranchers, and private forest owners keep their lands and survive this economic crisis. This announcement will help signal to land trusts, landowners, agencies, and stakeholders that additional resources are on the way and that interested landowners should consider conservation easements as tools that can help them weather the economic crisis.

- In the next 30 days: Request data and input from federal agencies, state governments, tribal governments, land trusts, conservation organizations, and external experts on expected demand for conservation easement programs over the next two years. This call for input could be organized and led by any member, group of members, or committee, but the results should be made public and shared with all committees that have jurisdiction over conservation easement programs.

- In the next 60 days: Hold congressional hearings or meetings with landowners, land trusts, tribal leaders, state leaders, conservation experts, and federal agencies to determine how programs can be improved in the near term to accelerate participation and ensure successful implementation.

- In the next 90 days: Draft emergency legislation to increase investments in existing conservation easement programs across the USDA, the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI), and the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD); enact short-term reforms to speed projects to completion; and establish new pilot programs to fill gaps among existing conservation easement programs. This legislation should be included and passed as part of any economic relief package that Congress considers.

Following this timeline would put Congress in a position to pass the Race for Nature relief legislation as early as September 2020. Congress could also move even more quickly by assembling existing ideas and recommendations for expanding investments in conservation easement programs. A letter signed by 79 members of the House, for example, recommends that Congress appropriate at least $6 billion to protect and restore private lands, including through increased funding for the Healthy Forests Reserve Program, the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program, and the Regional Conservation Partnership Program at the USDA, all of which fund conservation easements.24

As part of the rescue phase of the Race for Nature, the Center for American Progress recommends that, in addition to adding funding to existing federal conservation easement programs, Congress:

- Create a new component within the Forest Legacy Program to invest an additional $140 million annually in projects that protect forests with high carbon sequestration values.25

- Establish a pilot program that allows the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service maximum flexibility to rapidly implement conservation easements across a large diversity of landscapes and ecosystems to maximize carbon sequestration and protect biodiversity. This program should provide the agency the ability to experiment with alternative valuation methodologies and allow land trusts to hold easements, where beneficial and appropriate. Currently, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s easement programs focus on wetlands and grasslands for migratory birds, with limited funding to protect habitat for listed species and to support existing wildlife refuges. This approach is far too limited to appropriately address the urgency and scale of the nature crisis.

- Pass the Charitable Conservation Easement Program Integrity Act to halt the abuse of the current conservation easement tax incentive through syndications.26

Phase 2: Helping rural economies recover through a sustained investment in private land conservation

After the first phase of delivering immediate relief to family farmers, ranchers, and private forest owners at risk of losing their lands, Congress should turn its attention to implementing a longer-term vision for private land conservation.

In this second, recovery phase of the Race for Nature, Congress should take the following steps.

Establish long-term national goals for private land conservation

Congress could set a goal of protecting at least 3 million acres of land through conservation easements in 2021, with an associated goal of sequestering at least 1 million tons of carbon on these lands. Each year, this annual target would increase, so that by 2030, 55 million acres of private lands would be newly and permanently protected from development and 70 million tons of carbon would be sequestered.27 Congress should require the secretary of the interior and the secretary of agriculture to jointly report annually on the nation’s progress toward these land conservation and carbon sequestration goals.

Develop national priorities for private land conservation

To better align the goals of the existing medley of federal conservation easement programs, Congress should direct the DOI, the USDA, and the DOD to convene state agencies, tribal leaders, experts, and landowners to identify clear priorities for private land conservation across the country. Existing state and tribal wildlife action plans can serve as a starting point for identifying lands and waters where conservation easement programs should focus.28 It is critically important, however, that this plan also yield a more equitable distribution of nature’s benefits across all communities, including communities of color and economically disadvantaged communities. Federal conservation easement dollars should be purposefully directed to communities that are being disproportionately affected by nature loss, pollution, and the impacts of climate change.

Learn from and build on Phase 1

Congress should closely monitor the performance of programs and reforms implemented under the rescue phase of the Race for Nature in order to answer the following questions: Which programs were most nimble, easiest for landowners to navigate, and delivered the highest returns for nature conservation and carbon sequestration? Which new pilot programs and reforms should be expanded upon and made permanent? Should some programs be eliminated or combined? Are there other enduring but nonpermanent conservation tools that could developed, expanded, or modified to help landowners sustain the health of natural areas on their lands? And importantly, what sustained investments need to be made to enable the United States to meet the Race for Nature’s long-term land conservation and carbon sequestration goals? The answers to these questions should be incorporated into the 2023 Farm Bill and other nature conservation legislation that Congress will need to pass in the years ahead.

Make private land conservation more accessible and understandable

To help private landowners navigate the many federal conservation easement programs, the secretary of the interior and the secretary of agriculture should establish a single, unified, user-friendly website and application process for all federal conservation easement programs. The federal government should improve its data management for easements, including by updating the National Conservation Easement Database, further improving publicly available land cover databases, and creating better ways to monitor implementation of federally funded conservation easements that land trusts would hold.

Conclusion

Before the coronavirus pandemic, many family farmers, ranchers, and private forest owners were already in dire economic straits. Rising input costs, falling commodity prices, and the Trump administration’s trade war with China caused farm debt in the United States to rise to a projected $425 billion in 2020.29 Chapter 12 bankruptcies for farms have increased 24 percent since 2018, with even higher regional increases in Midwestern states.30 Now, with food processing facilities disrupted by COVID-19 outbreaks, restaurants struggling to get by, and global trade further slowing, the nation’s agricultural producers are facing a bleak economic future. Family farmers and ranchers need lifelines; and a bold and swift investment in nature conservation can provide one.

Launching the Race for Nature would help America’s rural communities weather the current economic storm while allowing the United States to make unprecedented gains in the conservation of clean water, clean air, and healthy wildlife. With scientists recommending that the United States and other countries protect at least 30 percent of all lands and ocean by 2030 (30×30), the United States can make dramatic strides toward this goal by rapidly expanding the availability and accessibility of conservation easements across the country. By launching the Race for Nature in two phases—a rescue phase and a recovery phase—Congress can meet both the urgent economic needs of family farmers and ranchers, while also establishing a bold, science-based, long-term vision for private land conservation that will safeguard nature for every community in America.

About the authors

Ryan Richards is a senior policy analyst for Public Lands at the Center for American Progress.

Matt Lee-Ashley is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress.

To find the latest CAP resources on the coronavirus, visit our coronavirus resource page.