For close to 80 years the Federal Housing Administration has helped millions of working-class families achieve homeownership and has promoted stability in the U.S. housing market—all at no cost to taxpayers. The government-run mortgage insurer is a critical part of our economy, helping first-time homebuyers and other low-wealth borrowers access the long-term, low down-payment loans they need to afford a home.

More recently, the agency prevented a complete collapse in the housing market, likely saving us from a double-dip recession. As private investors retreated from the mortgage business in the wake of the worst housing crisis since the Great Depression, the Federal Housing Administration increased its insurance activity to keep money flowing into the market. Without the agency’s support, it would have been much more difficult for middle-class families to get a home loan since the crisis began. Home prices would have plummeted even further, households would have lost much more wealth than they already did during the crisis, and even more families would have lost their homes to foreclosure.

A further decline in the housing market would have sent devastating ripples throughout our economy. By one estimate, the agency’s actions prevented home prices from dropping an additional 25 percent, which in turn saved 3 million jobs and half a trillion dollars in economic output.

What does the Federal Housing Administration do?

The Federal Housing Administration is a government-run mortgage insurer. It doesn’t actually lend money to homebuyers but instead insures the loans made by private lenders, as long as the loan meets strict size and underwriting standards. In exchange for this protection, the agency charges up-front and annual fees, the cost of which is passed on to borrowers.

During normal economic times, the agency typically focuses on borrowers that require low down-payment loans—namely first time homebuyers and low- and middle-income families. During market downturns (when private investors retract, and it’s hard to secure a mortgage), lenders tend rely on Federal Housing Administration insurance to keep mortgage credit flowing, meaning the agency’s business tends to increase. Through this so-called countercyclical support, the agency is critical to promoting stability in the U.S. housing market.

The Federal Housing Administration is expected to run at no cost to government, using insurance fees as its sole source of revenue. In the event of a severe market downturn, however, the FHA has access to an unlimited line of credit with the U.S. Treasury. To date, it has never had to draw on those funds.

But the agency was not immune to the housing crisis. Today it faces mounting losses on loans that originated as the market was in a freefall. Housing markets across the United States appear to be on the mend, but if that recovery slows, the agency may soon require support from taxpayers for the first time in its history.

If that were to happen, any financial support would be a good investment for taxpayers. Over the past four years, the Federal Housing Administration’s efforts saved families billions of dollars in home equity (a 25-percent drop in home prices translates to about $3 trillion in lost property values today), kept interest rates from skyrocketing (and with them monthly mortgage payments), and helped millions of workers keep their jobs. Any support would amount to a tiny fraction of the agency’s contribution to our economy in recent years. (We’ll discuss the details of that support later in this brief.)

In addition, any future taxpayer assistance to the agency would almost certainly be temporary. The reason: Mortgages insured by the Federal Housing Administration in more recent years are likely to be some of its most profitable ever, generating surpluses as these loans mature. This is due in part to new protections and tightened underwriting standards put in place by the Obama administration.

The chance of government support has always been part of the deal between taxpayers and the Federal Housing Administration, even though that support has never been needed. Since its creation in the 1930s, the agency has been backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, meaning it has full authority to tap into a standing line of credit with the U.S. Treasury in times of extreme economic duress—and no act of Congress is necessary. Extending that credit isn’t a bailout—it’s fulfilling a legal promise.

Looking back on the past half-decade, it’s actually quite remarkable that the Federal Housing Administration has made it this far without our help. Five years into a crisis that brought the entire mortgage industry to its knees and led to unprecedented bailouts of the country’s largest financial institutions, the agency’s doors are still open for business. This issue brief puts the agency’s current financial troubles in perspective. It explains the role that the Federal Housing Administration has had in our nascent housing recovery, provides a picture of where our economy would be today without it, and lays out the risks in the agency’s $1.1 trillion insurance portfolio.

Without the Federal Housing Administration, the housing downturn would have been much worse

Since Congress created the Federal Housing Administration in the 1930s through the late 1990s, a government guarantee for long-term, low-risk loans—such as the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage—helped ensure that mortgage credit was continuously available for just about any creditworthy borrower. In the decades leading up to the recent crisis, the agency served a small but meaningful segment of the U.S. housing market, focusing mostly on low-wealth households and other borrowers who were not well-served by the private market.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the mortgage market changed dramatically. New subprime mortgage products backed by Wall Street capital emerged, many of which competed with the standard mortgages insured by the Federal Housing Administration. These products were often poorly underwritten (if underwritten at all) and were easier to process than FHA-backed loans, often translating into far better compensation for their originators. This gave lenders the motivation to steer borrowers toward higher-risk and higher-cost subprime products, even when they qualified for safer FHA loans.

As private subprime lending took over the market for low down-payment borrowers in the mid-2000s, the agency saw its market share plummet. In 2001 the Federal Housing Administration insured 14 percent of home-purchase loans; by 2005 that number had decreased to less than 3 percent.

The rest of the story is well-known. The influx of new and largely unregulated subprime loans contributed to a massive bubble in the U.S. housing market. In 2008 the bubble burst in a flood of foreclosures, leading to a near collapse of the housing market. Wall Street firms stopped providing capital to risky mortgages, banks and thrifts pulled back, and subprime lending essentially came to a halt. The mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, facing massive losses on their own risky mortgage investments, were placed under government conservatorship and significantly scaled back lending, especially for home-purchase loans with low down payments.

The Federal Housing Administration’s lending activity then surged to fill the gap left by the faltering private mortgage market. By 2009 the agency had taken on its biggest book of business ever, backing roughly one-third of all home-purchase loans. Since then the agency has insured a historically large percentage of the mortgage market, and in 2011 backed roughly 40 percent of all home-purchase loans in the United States.

By playing this key countercyclical role, the Federal Housing Administration ensured that middle-class families could still buy homes, preventing a more devastating market downturn caused by a halt in home sales. The agency has backed more than 4 million home-purchase loans since 2008 and helped another 2.6 million families lower their monthly payments by refinancing. Without the agency’s insurance, millions of homeowners might not have been able to access mortgage credit since the housing crisis began, which would have sent devastating ripples throughout the economy.

It’s difficult to quantify the agency’s exact contribution to our economy in recent years. But when Moody’s Analytics studied the topic in the fall of 2010, the results were staggering. According to preliminary estimates, if the Federal Housing Administration had simply stopped doing business in October 2010, by the end of 2011 mortgage interest rates would have more than doubled; new housing construction would have plunged by more than 60 percent; new and existing home sales would have dropped by more than a third; and home prices would have fallen another 25 percent below the already-low numbers seen at this point in the crisis.

A second collapse in the housing market would have sent the U.S. economy into a double-dip recession. Had the Federal Housing Administration closed its doors in October 2010, by the end of 2011, gross domestic product would have declined by nearly 2 percent; the economy would have shed another 3 million jobs; and the unemployment rate would have increased to almost 12 percent, according to the Moody’s analysis.

“[The Obama administration] empowered the Federal Housing Administration to ensure that households could find mortgages at low interest rates even during the worst phase of the financial panic,” wrote Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, in The Washington Post last month. “Without such credit, the housing market would have completely shut down, taking the economy with it.”

The Federal Housing Administration was available when other insurers were not but became vulnerable to losses in the process

Despite a long history of insuring safe and sustainable mortgage products, the Federal Housing Administration was still hit hard by the foreclosure crisis. The agency never insured subprime loans, but the majority of its loans did have low down payments, leaving borrowers vulnerable to severe drops in home prices.

The agency is currently facing massive losses on loans insured in the later years of the housing bubble and the early years of the financial crisis, when lenders starting turning to the agency to sustain their origination volume and certain homebuyers found few alternatives to FHA-insured loans (mainly those who didn’t have pristine credit and cash for a 20-percent down payment). These losses are the result of a higher-than-expected number of insurance claims, resulting from unprecedented levels of foreclosure during the crisis.

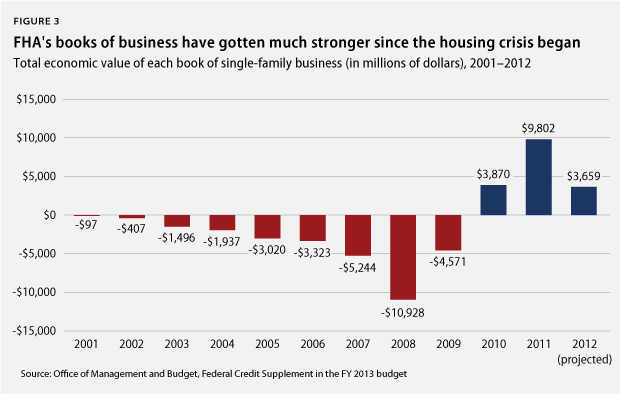

According to recent estimates from the Office of Management and Budget, loans originated between 2005 and 2009 are expected to result in an astounding $27 billion in losses for the Federal Housing Administration. The 2008 book of business alone accounts for about $11 billion of those losses, making it the worst book in the agency’s history by just about any metric (the agency eventually strengthened its business by issuing new underwriting standards and other protections that took effect second fiscal quarter of 2009—which we’ll discuss later in this issue brief.)

These books of business have a high concentration of so-called seller-financed down payment assistance loans, in which sellers covered the required down payment at the time of purchase often in exchange for inflated purchase-prices. Seller-financed loans were often riddled with fraud and tend to default at a much higher rate than traditional FHA-insured loans. They made up about 19 percent of the total origination volume between 2001 and 2008 but account for 41 percent of the agency’s accrued losses on those books of business, according to the agency’s latest actuarial report.

For years the Federal Housing Administration tried to eliminate seller-financed down payment assistance from its programs but met strong opposition in Congress, thanks in part to a “well-coordinated lobbying effort by a coalition of the nonprofit companies, housing and minority groups and home builders,” according to The Wall Street Journal. Congress finally banned seller-financed loans from the agency’s insurance programs in the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 (which didn’t actually take effect until the second fiscal quarter of 2009). If such a ban had been in place from the start, the agency could have avoided more than $14 billion in losses, which would have put it in a much better capital position going into the crisis, according to the latest actuarial report.

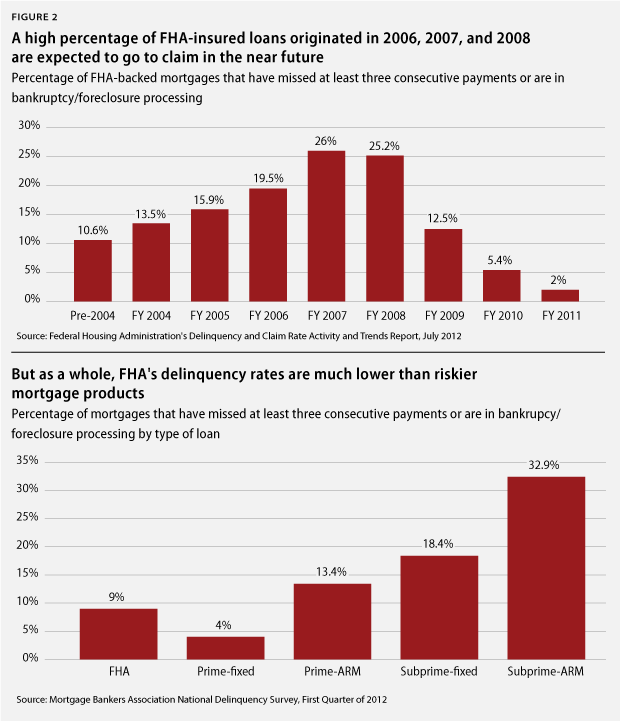

While millions of FHA-backed loans have already ended in an insurance claim that had to be paid by the agency, millions more are still in the foreclosure pipeline. For instance, roughly one in four outstanding FHA-backed loans made in 2007 or 2008 is “seriously delinquent,” meaning the borrower has missed at least three payments or is in bankruptcy or foreclosure proceedings.

A disproportionate percentage of the agency’s serious delinquencies are seller-financed loans that originated before January 2009 (when such loans got banned from the agency’s insurance programs). According to agency estimates, roughly 725,000 FHA-backed loans are seriously delinquent today, and about 14 percent of those loans had seller-financed down-payment assistance. By comparison, seller-financed loans make up just 5 percent of the agency’s total insurance in force today.

As riskier loans pass through the system, the agency’s more recent books of business are very strong

While the losses from loans originated between 2005 and early 2009 will likely continue to appear on the agency’s books for several years, the Federal Housing Administration’s more recent books of business are expected to be very profitable, due in part to new risk protections put in place by the Obama administration. Beginning in 2009 the agency increased insurance premiums four times—to the highest levels in its history. It also enforced new rules that require borrowers with low credit scores to put down higher down payments, took steps to control the source of down payments, overhauled the process through which it reviews loan applications, and ramped up efforts to minimize losses on delinquent loans.

As a result of these and other changes enacted since 2009, the 2010 and 2011 books of business are together expected to bolster the agency’s reserves by nearly $14 billion, according to recent estimates from the Office of Management and Budget. The new 2012 book of business is projected to add another $3.7 billion to their reserves, further balancing out losses on previous books of business.

These are, of course, just projections, but the tightened underwriting standards and increased oversight procedures are already showing signs of improvement. At the end of 2007 about 1 in 40 FHA-insured loans experienced an “early period delinquency,” meaning the borrower missed three consecutive payments within the first six months of origination—usually an indication that lenders had made a bad loan. That number is closer to 1 in 250 today.

The agency’s capital reserves are still uncomfortably low today

Despite these improvements, the capital reserves in the Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund—the fund that covers just about all the agency’s single-family insurance business—are uncomfortably low. Each year independent actuaries estimate the fund’s economic value: If the Federal Housing Administration simply stopped insuring loans and paid off all its expected insurance claims over the next 30 years, how much cash would it have left in its coffers? Those excess funds, divided by the total amount of outstanding insurance, is known as the “capital ratio.”

The Federal Housing Administration is required by law to maintain a capital ratio of 2 percent, meaning it has to keep an extra $2 on reserve for every $100 of insurance liability, in addition to whatever funds are necessary to cover expected claims. As of the end of 2011, the fund’s capital ratio was just 0.24 percent, about one-eighth of the target level.

The agency has since recovered more than $900 million as part of a settlement with the nation’s biggest mortgage servicers over fraudulent foreclosure activities that cost the agency money. While that has helped to improve the fund’s financial position, many observers speculate that the capital ratio will fall even further below the legal requirement when the agency reports its finances in November.

This is a legitimate concern but not one that should be overstated. As required by law, the Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund still holds $21.9 billion in its so-called financing account to cover all of its expected insurance claims over the next 30 years using the most recent projections of losses. The fund’s capital account has an additional $9.8 billion to cover any unexpected losses.

That’s not enough to meet the 2 percent capital ratio target, but the agency still has plenty of cash on hand to cover its insurance liabilities based on reasonable expectations in the housing market—and even has some extra money set aside for a rainy day.

That said, the agency’s current capital reserves do not leave much room for uncertainty, especially given the difficulty of predicting the near-term outlook for housing and the economy. In recent months, housing markets across the United States have shown early signs of a recovery. If that trend continues—and we hope it does—there’s a good chance the agency’s financial troubles will take care of themselves in the long run.

But if the recovery stalls and home prices begin to dip lower—which likely would cause another wave of foreclosures—the Federal Housing Administration’s capital cushion may not be sufficient. In that unfortunate event, the agency may need some temporary support from the U.S. Treasury as it works through the remaining bad debt in its portfolio. This support would kick in automatically—it’s always been part of Congress’ agreement with the agency, dating back to the 1930s—and would amount to a tiny fraction of the agency’s portfolio. It would also be a bargain, considering how taxpayers have benefitted from the agency over the past eight decades—and especially the past four years.

The Federal Housing Administration’s current financial troubles must be kept in perspective

How would taxpayer “support” to the Federal Housing Administration work?

Once a year the Federal Housing Administration moves money from its capital account to its financing account, based on re-estimated expectations of insurance claims and losses. (Think of it as moving money from your savings account to your checking account to pay your bills.) If there’s not enough in the capital account to fully fund the financing account, money is drawn from an account in the U.S. Treasury to fill the gap.

Such a transfer does not require any action by Congress. Like all federal loan and loan guarantee programs, the Federal Housing Administration’s insurance programs are governed by the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990, which permits them to draw on Treasury funds if and when they are needed.

It’s rather astonishing that the Federal Housing Administration made it this far without requiring taxpayer support, especially in light of the financial troubles the agency’s counterparts in the private sector experienced. In the wake of the crisis, most private mortgage insurers have either gone out of business or significantly scaled back their insurance activity, while the agency meaningfully increased its insurance activity to help keep the market afloat and prevent another crisis.

If the agency does require support from the U.S. Treasury in the coming months, taxpayers will still walk away on top. The Federal Housing Administration’s actions over the past few years have saved taxpayers billions of dollars by preventing massive home-price declines, another wave of foreclosures, and millions of terminated jobs. Considering the strength of the agency’s recent books of business, any temporary assistance would almost certainly be paid back over a reasonable time frame.

To be sure, there are still significant risks at play. There’s always a chance that our nascent housing recovery could change course, leaving the agency exposed to even bigger losses down the road. That’s one reason why policymakers must do all they can today to promote a broad housing recovery, including supporting the Federal Housing Administration’s ongoing efforts to keep the market afloat.

Regardless of how the mortgage market changes in the coming years, the agency continues to serve a vital purpose, both by expanding homeownership to underserved segments of the market and by providing liquidity in times of economic duress. The agency has filled both roles dutifully in recent years, helping us avoid a much deeper economic downturn. For that, we all owe the Federal Housing Administration a debt of gratitude and our full financial support.

John Griffith is a Policy Analyst with the Housing team at the Center for American Progress.