Introduction and summary

On August 3, 2017, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke spent his afternoon and evening with David Lesar, the chairman of oil services giant Halliburton. The two men met in Zinke’s lavish Interior Department offices, toured the Lincoln Memorial together, and then had dinner at a popular Washington, D.C., beer garden.1

The details of Zinke and Lesar’s conversations are not yet known, but according to a participant in the day’s meetings, the main topic was not energy policy or oil production but instead a real estate deal in Whitefish, Montana, that would reportedly deliver private financial benefits to both men.2 The real estate deal; Zinke’s alleged use of public office for personal financial gain; and the question of whether Halliburton has improperly benefited from Lesar’s financial ties to Zinke have rightly attracted the scrutiny of watchdog groups, congressional investigators, and Interior’s inspector general.3

Both Zinke and Lesar have acknowledged the real estate deal and meeting in the secretary’s office, and they have dismissed any wrongdoings.4 However, the emerging scandal may be part of a string of questionable decisions rather than an isolated incident. The Center for American Progress reviewed financial and lobbying disclosure forms of Trump administration officials, as well as Interior Department decisions, media reports, and other government records. The findings indicate that President Donald Trump’s Interior Department may be establishing a standard of behavior that hands out favorable decisions—which may carry substantial financial benefits—to political patrons and past clients of senior political appointees in the Department of the Interior (DOI). In some cases, by doing so, the department has dismissed ethical norms. This pattern of behavior mirrors the culture of corruption that has taken root in President Trump’s White House, at former Administrator Scott Pruitt’s Environmental Protection Agency, and in other Trump administration cabinet agencies.5

Zinke’s own behaviors and actions—from his real estate deal with Lesar to his mixing of political, personal, and government business on taxpayer-funded trips—create an ethically questionable culture within the Department of the Interior’s leadership. Yet it is Zinke’s deputy secretary, David Bernhardt—previously a lobbyist on issues he now oversees—who appears to be a central figure in a carefully constructed clientelistic system for dispensing political favors. The authors of this report characterize this system as the Interior Department’s “favor factory.”

Bernhardt, who led then-President-elect Trump’s transition team for the Department of the Interior, first served in the Interior Department as a political appointee in the administration of former President George W. Bush. He served as senior aide to then-Interior Secretary Gale Norton before being promoted to serve as the Interior Department’s top lawyer.6 As solicitor, Bernhardt authored several controversial legal opinions, including ones that made it more difficult to designate endangered species.7 After leaving the department in 2009, Bernhardt rejoined the Washington, D.C., office of Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, where he lobbied for mining companies, oil and gas companies, powerful water users in the West, and other groups that have a financial interest in decisions that are made by the Department of the Interior. In August 2017, he was sworn in as Interior’s deputy secretary.

This report will explore three notable features of the favor factory at the Interior Department. First, it will examine how Trump administration political appointees at the Interior Department can exploit weakened federal ethics guidelines to work in positions where they can deliver favorable decisions to past clients and mask their portfolio of responsibilities from public inspection. Second, it will analyze recent Interior Department decisions that are favorable to past clients of former lobbyists and litigants who are working in Trump’s Department of the Interior. Finally, the report will examine some of the operational characteristics of the Interior Department’s favor factory that mask it from public view.

This report does not make any claims that Trump administration officials at the Interior Department have violated any federal laws or regulations; rather, it describes the contours of what is currently known and not known about the Trump administration’s practices at the Department of the Interior. For example, the report lists four past clients of Deputy Secretary Bernhardt who have received or stand to receive financial benefits from specific decisions by the Trump administration’s Interior Department. These decisions merit scrutiny by congressional investigators in order to determine whether they were made in accordance with federal ethics and conflict of interest statutes and regulations. In addition, the report includes a “watch list,” which details other past clients of Bernhardt who have significant policy and business interests before the Interior Department. Congressional oversight committees should carefully monitor the deputy secretary’s engagement on these matters in order to ensure compliance with his recusals and ethics agreement.

The importance of strong congressional oversight of the Trump administration’s Interior Department cannot be overstated. The DOI Office of the Inspector General (OIG) and the U.S. Office of Special Counsel have already opened 11 investigations of Secretary Zinke’s actions, yet the 115th Congress has failed to hold a single hearing on possible ethical lapses by political appointees in Trump’s Interior Department.8 This failure by the Republican-led Congress to hold the executive branch accountable raises the risk that the Interior Department will once again endure the kind of scandal, scientific misconduct, and ethical violations that consumed the department during the George W. Bush administration.9 To avoid this outcome, congressional oversight committees should immediately begin to gather additional information, to request records, and to conduct interviews that can illuminate the operation of Interior’s favor factory.

In addition to conducting its oversight responsibilities, Congress should take legislative action to tighten ethics standards and to strengthen enforcement of conflict of interest laws. In particular, CAP recommends that Congress:

- Strengthen formal ethics standards for individuals working in the executive branch.

- Strengthen the Lobbying Disclosure Act by amending it to require lobbyists to provide more detailed information when filling out disclosure forms.

- Increase funding for Interior’s Office of the Inspector General in order to ensure proper oversight of the department.

- Require better records retention policies within the Interior Department and modernize the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

Enacting these standards and conducting rigorous independent oversight will strengthen the public’s trust in the Department of the Interior, safeguard the country’s public lands from special interests, and ensure that the agency’s decisions are made in a manner that serves the public interest.

The Trump administration’s weakened ethics policies

Upon taking office in 2009, then-President Barack Obama issued sweeping ethics and revolving door restrictions to be imposed on officials seeking to serve in his administration.10 His executive order was largely inspired by ethical lapses that defined the Bush administration’s Department of the Interior, including allegations of financial self-dealing, meddling with scientific findings, and the aftermath of the Jack Abramoff scandal.11

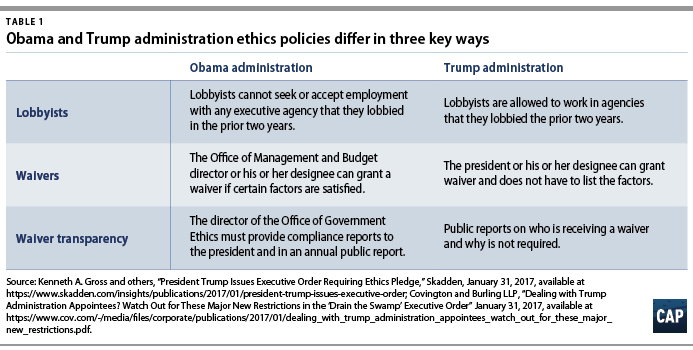

On January 28, 2017, President Donald Trump signed his own executive order on ethics. At first glance, it appears that the order is complementary to Obama’s ambitions to curb conflicts of interests within the administration.12 Both executive orders include “reverse revolving door” restrictions on those entering an administration: All appointees must pledge to recuse themselves from official actions that would directly and substantially affect their former employers or clients of the last two years.

However, Trump’s executive order removed a critical provision: banning individuals from seeking or accepting employment with any executive agency that they lobbied within the previous two years.13 David Bernhardt—who, until 2017, worked as a lobbyist and chairman for Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck’s natural resources department—was among the individuals who benefited from Trump’s elimination of the two-year lobbying ban. Bernhardt now serves as deputy secretary of the Interior. The removal of the Obama-era provision allows people like Bernhardt, who have years of experience in the private and public sectors, to be able to oversee policies at the Department of the Interior that could benefit former clients.

President Trump’s order also differs from Obama’s in two other important ways. First, it fails to clearly state who is charged with overseeing that mandated recusals take place. Unlike the Obama administration, Trump has failed to appoint an “ethics czar” or to implement a procedure ensuring all potential conflicts of interests are understood by newly appointed officials.14 Secondly, while both orders include exception waivers for some individuals, Trump’s removes a transparency provision that allows the public to know who has received such waivers.15

The favor factory delivers for former clients and political donors

Secretary Zinke’s eagerness to take actions that benefit political patrons and personal friends sets a negative example for other senior Interior Department officials, who may in turn follow his lead. Zinke’s subordinates, for example, might interpret the Interior Secretary’s questionable business interactions with the chairman of Halliburton as a sign that it is permissible to blur the line between official business and one’s personal financial gain. Likewise, Zinke’s decision to take a private chartered flight after giving a speech to the Vegas Golden Knights hockey team—which is owned by a political donor to Zinke’s past congressional campaign—might suggest to Interior Department officials that government resources can be used to reward political campaign supporters. In fact, many political pundits consider unethical behavior at top to be contagious.16 The Interior Department’s inspector general found that the trip, which cost taxpayers upwards of $12,000 and did not relate to the department’s business, “could have been avoided.”17 Furthermore, although the Trump administration’s Interior Department has made numerous decisions that financially benefit the hunting and gun industries, Secretary Zinke’s failed to disclose that he was a shareholder in a firearms company, PROOF Research Inc., conveying a lack of respect for federal financial disclosure requirements.18

Indeed, the Department of the Interior’s culture now reflects Zinke’s poor example, and senior political appointees appear to be permitted to work on policy matters that could benefit former clients and employers. These close personal and professional connections to senior Interior Department officials may allow former employers to have direct access to decision-makers that the average citizen does not have. For example:

- The department’s senior deputy director for intergovernmental and external affairs, Benjamin Cassidy, is a former National Rifle Association (NRA) lobbyist and has since participated in a number of positive decisions for his former employer of seven years. In one example, according to Secretary Zinke’s public calendar, Cassidy participated in a “Monument After Action Meeting” in December 2017, about two weeks after the Trump administration eliminated huge portions of the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments. Earlier that year as an NRA lobbyist, Cassidy lobbied on a bill that would have prevented presidents from designating national monuments without approval from Congress and state legislatures. Cassidy has not responded to media requests about these reports.19

- Doug Domenech, assistant secretary of the interior for insular areas, met with his former employer, the Koch-linked Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF), while the company was involved in legal action against the department. Six months after their meeting, TPPF announced that it had settled its lawsuit with the Interior Department, calling it a “major win.” The Interior Department insists that the meetings were “primarily social in nature”; however, public scheduling calendars show they concerned policy. Domenech reported the meetings to ethics officials, and the department is addressing the matter internally, according to an Interior Department spokesperson.20

- Zinke’s senior adviser for Alaska Affairs, Steve Wackowski, was formerly employed by two Alaska companies now tied to a group that is seeking DOI approval to conduct seismic studies for oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Wackowski has not commented on media reports on this topic.21

The Interior Department’s recent handling of American Indian gaming decisions is also illuminating. In 2017, the department signaled that it would approve, through its normal process, an application by two tribal nations in Connecticut—the Mashantucket Pequot and Mohegan tribes—to build a new casino. MGM Resorts, however, which is building its own casino nearby in Massachusetts, opposes the tribes’ plans. In early September 2017, lobbyists for MGM Resorts and one of its lobbying firms, Ballard Partners, joined Secretary Zinke for drinks on his balcony. Two weeks later, the Interior Department said that it would not approve the tribes’ casino proposal.22 Records also show that Deputy Secretary Bernhardt and Associate Deputy Secretary James Cason had numerous meetings with MGM’s lobbyists, including former Interior Secretary Gale Norton.23 Though Bernhardt has brushed off the meeting with Norton as merely a “social visit,” his former lobbying firm also represents MGM, and per his ethics agreement, he is barred from participating in particular matters with which he was involved while working for his previous employer.24 When asked by reporters, both Cason and Interior Department spokespersons declined to comment on the informal meetings with MGM.25 After media reports emerged about Zinke, Bernhardt, and Cason’s apparent intervention on behalf of MGM Resorts, the Interior Department allowed the gaming proposal from the Mohegan tribe to move forward—but not that of the Mashantucket Pequot, leaving the tribe‘s casino in limbo for the time being.26

Spotlight: Deputy Secretary Bernhardt’s revolving door

Deputy Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt’s alleged involvement in a gaming decision that affected a client of his former firm appears to fit a pattern that merits closer scrutiny.

Bernhardt was nominated to serve as Interior’s deputy secretary in April 2017, confirmed by the U.S. Senate in July 2017, and formally sworn in on August 1, 2017.27 A mainstay in Washington political circles, he has spent the last quarter century working on Capitol Hill, in the executive branch, and in the lobbying industry.

As second in command at the Department of the Interior, the deputy secretary is considered both the chief financial officer and chief operating officer of a nearly 70,000-employee agency.28 In his current position, Bernhardt oversees major expenditures, scientific integrity, and the department’s ethics team. He also has been assigned management of several projects that are of high priority for Secretary Zinke, such as overhauling sage-grouse management plans, opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling, and reducing regulatory oversight of the oil and gas industry. Notwithstanding his sweeping responsibilities, Bernhardt pledged to recuse himself from working on particular matters involving 26 parties for a period of at least one year—and, in the case of 22 of these parties, for a period of two years.29

As a practical matter, the breadth of business interests that Bernhardt’s past clients have before the Interior Department make it difficult for the deputy secretary to effectively eliminate any real or perceived conflicts of interest in the performance of his duties. Indeed, this review of recent Interior Department decisions identifies at least three instances—in addition to MGM resorts—in which past clients of Bernhardt have gained specific, favorable outcomes from the Department of the Interior. The Department of the Interior’s press office failed to provide comment to CAP on this matter. It is vitally important that Congress conduct thorough investigations of these incidents in order to ensure that the deputy secretary is abiding by his recusals.

Cadiz Inc.

From 2010 through late 2016, private water company Cadiz Inc. paid Bernhardt and his former firm $2.75 million for legal and lobbying services.30 During the period in which Bernhardt was working for Cadiz, the company was seeking federal and state approvals of a controversial project to pump groundwater from an aquifer underneath the Mojave Desert and pipe it to cities in Southern California. Scientists warn that the proposed project would cause severe damage to the Mojave National Preserve and Mojave Trails National Monument.31

After failing to receive necessary approvals from the Obama administration, the Cadiz project’s prospects looked bleak. That changed following the 2016 elections, when the project landed on a list of priority projects reportedly put together by Trump’s transition team—on which Bernhardt occupied a leadership position. Shortly afterward, Cadiz’s stock rose to its highest level in nearly a decade.32 In May 2017, the Interior Department began issuing orders to clear the way for the Cadiz project to go through, and in September 2017, the DOI Office of the Solicitor issued a favorable legal opinion that allowed the project to move forward.33 Subsequently, in October 2017, the Bureau of Land Management reversed an Obama-era decision and determined that Cadiz does not need Interior Department approval to build its pipeline.34 Bernhardt claims that he was not involved in the Cadiz decision and will not personally benefit from the change in policy.35

According to Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings, Bernhardt’s former lobbying firm is promised an additional 200,000 shares of Cadiz stock if the company makes progress toward completing the project.36

Garrison Diversion Conservancy District

Bernhardt received over $5,000 for legal services he provided to the Garrison Diversion Conservancy District (Garrison) as recently as 2016. In 2017, his former law firm received $30,000 for its lobbying efforts, and it has received $40,000 in 2018 so far.37

In January 2016, the water district hired Bernhardt to assist with a plan that would supplement water supplies in the Red River Valley by using the McClusky Canal to draw Missouri River water.38 The project has faced severe environmental and budgeting opposition.39 In early 2017—around the same time Bernhardt was nominated as deputy secretary—Garrison hired Brownstein as a lobbying firm.

Prior records show that, in April 2017, Bernhardt spoke to Garrison’s board of directors at a meeting, alongside two Brownstein lobbyists who were registered on behalf of the water district.40 On July 24, 2017, two days after the Senate approved Bernhardt’s nomination, Garrison affirmed that it was formally requesting permission from the Interior Department to use the McClusky Canal to draw Missouri River water.41 When Bernhardt was sworn in on August 1, 2017, he vowed to recuse himself from matters dealing with Garrison until just August 2018, despite having worked on its behalf up until his confirmation.42

Garrison’s water project had been considered discarded until Donald Trump took office, but news outlets are now reporting that optimism is building among officials on the project.43 One member of the water project’s board, Ken Vein, said, “We want to have a substantial start now while we’re dealing with the current administration.”44 The company also has been granted access to Secretary Zinke. In October 2017, members of the Garrison Diversion Conservancy District met with Zinke in Washington, D.C., and in May 2018, Zinke made a visit to North Dakota to see their facilities.45 In 2018, Brownstein increased its monthly retainer fee from $3,500 to $10,000, citing, “Our firm has professionals who have held leadership positions at the Department of the Interior … Many of the decision makers in the agencies are former co-workers and colleagues.”46 Congress should conduct proper oversight in order to ensure that the deputy secretary is abiding by his recusals and that his former firm has not been given favorable access to Interior Department decision-makers.

Eni Petroleum

In his paperwork, Bernhardt recuses himself from working on issues related to the oil and gas company Eni Petroleum.47

In April 2017, President Trump issued an executive order overturning the protections that former President Obama had put on Arctic waters.48 In August 2017, David Bernhardt was sworn in and recused himself from participating in matters related to Eni Petroleum; three months later, the oil and gas giant became the first company approved to drill in federal Arctic waters since 2015.49 On December 24, 2017, in an email to a reporter, Interior Press Secretary Heather Swift stated that employees from the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) were “working through Christmas to get Eni permitted [for Arctic drilling],” noting that it would be a “nice Christmas present.”50

The suggestion that Eni’s permit was rushed to completion over a federal holiday raises questions of whether additional taxpayer dollars were expended on the permit—for example, on overtime and/or on keeping offices open—and whether Bernhardt had any role in encouraging that extraordinary measures be taken to expedite the permit. These are questions that congressional investigators should explore.

Watch list

In addition to previous clients who have received favorable decisions on particular matters before the Department of the Interior, CAP’s analysis identified several additional past clients of Bernhardt who have benefited from policy decisions made by the Trump administration. Congressional oversight committees should ensure that these entities do not yield improper influence, and they should carefully monitor Bernhardt’s engagement with these past clients. Several pending FOIA requests may provide further insight into the contact these past Bernhardt clients have had with the Interior Department.

State of Alaska

In 2014, Bernhardt represented the state of Alaska in a lawsuit against the Interior Department that aimed to force the Obama administration to allow new seismic exploration in the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, with the ultimate goal of allowing oil drilling in the Arctic Refuge.51 In 2015, a U.S. District Court judge ruled against the state of Alaska.52 Bernhardt and his firm were paid upwards of $250,000 for their work.53

Less than two weeks after Bernhardt was sworn in as deputy secretary, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service wrote a draft memo that would change three decades of precedent and allow seismic testing in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.54 In December 2017, President Trump signed a sweeping tax measure into law, which included a provision that directs the interior secretary to create and administer a program to develop, produce, and lease the Arctic Refuge Coastal Plain for oil drilling.55 Bernhardt appears to be personally and directly involved in the Trump administration’s efforts to rush its approval of seismic and drilling activities in the refuge, as indicated by repeated comments in the media about the environmental review process and personal meetings with senior officials from the state of Alaska.56

Despite representing Alaska in its push to drill the Arctic Refuge, Bernhardt did not recuse himself from continuing to work on matters that benefit this former client.

Cobalt International Energy

Between 2010 and 2013, Bernhardt lobbied and provided legal services for oil exploration company Cobalt International Energy. His lobbying firm was paid almost $2 million by the company during those years.57 As of 2017, Cobalt still employs the lobbying company at which Bernhardt was a partner; Brownstein provides counsel for Cobalt regarding leasing and development on the outer continental shelf.

Cobalt has benefitted from the administration’s focus on offshore drilling as well as a number of pro-oil and pro-gas decisions, including the rollback of a ban on new offshore drilling off the coasts of Florida and California and an expansion of drilling in the Gulf of Mexico and in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic oceans.58 The company also presumably benefits from the weakening of rules put in place following the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe, including a proposed rule that would replace independent inspections of safety equipment with industry-led inspections, as well as one that would roll back safety test and data-reporting requirements. 59

Noble Energy

Bernhardt provided legal services to Noble Energy, a petroleum and natural gas production and exploration company, and he listed them as a source of more than $5,000 in annual income—from which he would recuse himself.60

The company recently announced that it is selling off its Gulf of Mexico oil holdings but continues to hold federal oil and gas leases in the West.61

Lobbying information from the Center for Responsive Politics shows that, in recent years, Noble Energy has frequently lobbied the Interior Department on issues relating both to oil and gas permitting and to the greater sage-grouse. Both issues are now under Bernhardt’s oversight.62

Westlands Water District

From 2011 through 2016, Bernhardt served as both a lobbyist and lawyer for Westlands, the largest agricultural water district in the nation, and his former lobbying firm continues to represent them.63 While Bernhardt deregistered as a lobbyist in November 2016, he continued to do consulting work for Westlands.64 The district paid him more than $20,000 for his work. Overall, from 2011 through 2016, more than one-third of the $3 million that Westlands spent on lobbying went to Bernhardt’s former firm.65 Of the nearly $900,000 Westlands has spent on lobbying since early 2017, more than half has gone to Bernhardt’s former firm.66

While Bernhardt was litigating on behalf of Westlands, he unsuccessfully sued the Interior Department and the National Marine Fisheries Service, the latter of which sought to prevent Westlands from pumping water from the San Francisco Bay Delta into the water district.67 At issue in that case was the protection of species listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act, such as the winter-run Sacramento River chinook salmon, the delta smelt, and the southern resident orca.68 Now, Bernhardt is running point for the department’s weakening of the Endangered Species Act, a law which he has described as an “unnecessary regulatory burden.”69

One of Westlands’ top priorities is to enlarge the Shasta Dam in the Sacramento Valley. The project would come at the expense of wildlife and recreationists, and it would potentially violate the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. Advocacy groups have already filed suit over the project’s threats to endangered salamanders.70 Earlier this year, the Interior Department said in a statement to the Los Angeles Times that its ethics officers had reviewed Bernhardt’s agreement with the department and advised that it does not require his recusal from decisions on the Shasta Dam.71 Congress should scrutinize Bernhardt’s recusals and whether it is appropriate for him to participate in discussions surrounding the enlargement of the Shasta Dam.72

In addition, just 13 days after Bernhardt’s ethics recusal from Westlands expired, Secretary Zinke tapped his deputy to oversee a project that aims to determine water delivery to California’s Central Valley Project and maximize water supply deliveries to irrigations districts south of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta—which includes Westlands.73

How the favor factory stays under the radar

Secretary Zinke’s Interior Department’s coziness with the special interests it is supposed to be regulating contributes to a culture of corruption that is both troubling and largely masked from public view.

Political staff at the department appear to be avoiding the creation of paper trails, delaying document productions, and shielding their actions from public inspection. The calendars of senior Interior Department officials, for example, are public documents that, by law, must be released. The release of these calendars, however, is consistently delayed—some, like that of acting Solicitor Daniel Jorjani, have not been posted since May 2017. Furthermore, the calendars often lack basic information about the purpose of meetings, the topics discussed, or whom the officials are meeting with.74

In addition, some of the publicly released calendars of senior Interior Department officials contain information that conflicts with other documents released under the FOIA, which suggests that calendar documents are being manipulated or sanitized for public release. For example, emails from Secretary Zinke’s scheduler show that he met with Halliburton representatives on August 3, 2017, but the entry on his official calendar is marked only as “HOLD.”75 A CNN investigation showed that Zinke has been omitting details about some meetings from his official calendar. For example, when he held a meeting in Alaska, Zinke failed to disclose that he was joined by lobbyists from a firm representing the North Slope Borough mayor’s office in a lawsuit against the department.76 In a response to that report, Zinke’s office said that it “complies with all applicable laws, rules, and regulations.”77 However, this lack of public-facing information leaves the American people almost entirely in the dark about what Interior’s political staff do on a daily basis, making it difficult to assess whether they are following ethics guidelines.

In addition to questions about the integrity of senior officials’ calendars, Trump’s Interior Department appears to be systematically suppressing or delaying the release of other documents that should be released under the FOIA. In December, for example, it was reported that high-level agency officials were reviewing FOIA documents before they were released, with some directed to go directly through Zinke’s office before being released.78 Likewise, a watchdog organization—Western Values Project—has questioned how it is possible that, in the 628 pages of FOIA records released about the Trump administration’s review of sage-grouse conservation plans, the name of the person in charge of the review, Deputy Secretary Bernhardt, only appears twice.79 These delays and apparent withholdings have prompted litigants to allege a “culture of secrecy” at the department.80

The effort by Zinke’s political appointees to minimize documentation of their decisions has been confirmed by two recent reports by the Interior Department’s inspector general: one investigating Zinke’s questionable travel practices and the other examining the mass reassignment of Senior Executive Service (SES) employees.81 The investigation dealing with the controversial reassignment of 27 senior executive officials found that poor record-keeping made it impossible to tell if the department acted legally. The report found that top Interior Department officials failed to document who was in charge, detail how reassignment decisions were made, or record “meeting minutes, notes, voting or decision records” related to reassignments.82 In both cases, Bernhardt was charged with responding to or acting on the findings; in both cases, he curiously responded to the inspector general’s criticism by blaming the previous administration for failing to implement guidelines and procedures that would have prevented the Trump administration’s poor record-keeping.83

Unsurprisingly, there has been a sharp jump in the number of lawsuits filed against the Trump administration—compared with previous administrations—to obtain federal government records.84 The Department of Interior is no exception to this Trump-era norm; most recently, an independent watchdog filed a lawsuit claiming that the department was withholding documents that show whether Bernhardt has met with his former lobbying clients.85

The role of congressional oversight

Congressional oversight is and always has been essential in ensuring that the Department of the Interior is faithfully and honestly fulfilling its responsibilities. In the 1920s, for example, a congressional investigation of Albert B. Fall—former President Warren G. Harding’s interior secretary—landed him in prison for accepting bribes from oil companies in exchange for granting oil leases.86 In the aftermath of that incident, known as the “Teapot Dome scandal,” Congress passed legislation that required disclosure for contributions of more than $100—a novel idea at the time.87

More recently, congressional oversight led to the resignation of J. Steven Griles, a former coal lobbyist who was appointed deputy secretary of the interior during the George W. Bush administration. In 2007, 2 1/2 years after his resignation, Griles was sentenced to 10 months in prison for a felony conviction of obstructing a Senate investigation into corrupt lobbyist Jack Abramoff.88 Those incidents led to the passing of the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act, which, among other things, strengthened public disclosure requirements concerning lobbying activity and instituted a “cooling-off” period for executive and congressional officials seeking to become lobbyists—during which they would be unable to seek official action on behalf of anyone else by either communicating with or appearing before specified current officials with the intent to influence them.89

As the Trump administration’s ethical lapses continue to rise, it is Congress’ role to use, and potentially expand, its oversight. The requirement of a stringent set of ethical guidelines will ensure that elected and appointed officials as well as lobbyists are free from conflicts of interest. CAP recommends that Congress take a number of actions:

- Congress should set a strong ethical standard for individuals working in the executive branch by, at a minimum, codifying into law the Obama administration’s 2009 ethics package. This would ensure continuity and transparency among administration officials as leadership changes. There are still stronger measures that could be taken to build a wall between acting for private financial interests and working in public service. For example, Congress should consider implementing a five-year ban on special interest lobbying; barring, for at least two years, government appointees involved in policy decision-making from working for private entities that have benefited from those policy decisions, and requiring government employees to recuse themselves for two years from cases involving their former employers.90

- The Lobbying Disclosure Act should be amended to require lobbyists to provide more detailed information when filling out disclosure forms. Congress should also require congressional offices and the executive branch to publish their lobbying contacts and publicly disclose whom they meet with as well as the subject of the meeting—particularly when specific policy matters are addressed.91

- Congress should increase funding for Interior’s Office of the Inspector General in order to ensure proper oversight of the department. The OIG has received flat funding since Fiscal Year 2015 and yet their investigation requests have increased by nearly 30 percent.92

- Congress should put in place stronger records retention policies, and in order to modernize the FOIA, it should narrow exemptions, fix loopholes, and strengthen the presumption of openness by codifying a requirement that agencies stop withholding information without a genuine reason to do so.93

Conclusion

Since being sworn in as the nation’s 52nd secretary of the interior, Zinke has led a department that has been subject to an unprecedented number of internal investigations. This troubling pattern ranges from weakened ethics rules, failed record-keeping, and slowed FOIA releases to handing out lucrative rewards to the political patrons and past clients of Secretary Zinke, Deputy Secretary Bernhardt, and other senior Trump administration officials. In sum, the Department of Interior has built a favor factory that remains largely hidden from public scrutiny. This internal policy strengthens the executive branch’s ability to curb transparency and deludes oversight of America’s public lands.

Congress has a responsibility to step in and use its critical tools to make sure that the department is holding employees accountable for their recusals, for their ethical agreements, and to the public. Using its proper oversight role, Congress can rebalance power in favor of the people and begin to rebuild trust in the Department of the Interior.

About the authors

Jenny Rowland is a senior policy analyst for Public Lands at the Center for American Progress.

Marc Rehmann is the senior campaign manager for the Center’s Law of the Land Project.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Matt Lee-Ashley, Danielle Schultz, Andrew Edkins, Nicole Gentile, Christy Goldfuss, Will Beaudouin, Keenan Alexander, Tricia Woodcome, and Steve Bonitatibus for their contributions to this report.