See also:

In March, Afghanistan President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah will make their first visit to the United States since assuming office under a power-sharing agreement reached in 2014. While the formation of a unity government settled months of political tension, the new coalition faces serious challenges. Of the many threats to Afghanistan’s long-term security and economic development, two stand out as especially persistent and grave. The foremost threat is the Taliban insurgency in the country’s South and East; the second most pressing issue is widespread corruption.

While these two challenges may seem very different in nature, they are in fact intimately connected. Pervasive graft in the government has created deep frustration with the Western-backed regime in Kabul and undermined the integrity of the Afghan administration. Corruption has critically weakened the Afghan military and police and impeded the flow of outside aid and investment to those most in need. These conditions have fueled insurgency in many parts of the country and created a void in delivering assistance and providing governmental services across Afghanistan.

The United States and other donors should seize on the political and public momentum to combat corruption in Afghanistan. It is essential to accelerate plans to assist Kabul in developing an arsenal of tools aimed at increasing accountability and transparency while reducing corruption and graft.

This issue brief surveys the key factors driving corruption in Afghanistan and their harmful impact on Afghanistan’s security and economic development. It also offers a set of recommendations and tools for combating corruption that should be prioritized by Afghan officials and supported by the United States and other donors.

Putting corruption front and center

This official visit by President Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah comes at a crucial moment for Afghanistan, as the country seeks to peacefully conclude the first democratic transfer of power in its modern history. It also comes during a delicate period in U.S.-Afghanistan relations, which entered a new phase last December following the formal end of the NATO combat mission in the country. The diminished U.S. and NATO military presence in Afghanistan means that the new government—already struggling to form a cabinet—will shoulder unprecedented responsibility for maintaining peace and stability over the coming months and years.

While there are many dire predictions for Afghanistan’s stability and future, the election of new leadership presents a new opportunity to prioritize efforts to improve governance, fight corruption, and enhance accountability. Both Ghani and Abdullah made anticorruption efforts a key component of their presidential campaigns. The political will to tackle graft in Afghanistan, and the demand from citizens to do so, is arguably greater than ever before.

Corruption is broadly defined as the abuse of entrusted authority—both public and private—for illegitimate gain. It is an impediment not only to economic growth and development, but also to political stability, democracy, and sustainable peace. In fragile and conflict-riddled countries such as Afghanistan, corruption can deeply undermine the effectiveness and legitimacy of nascent government institutions. As one active-duty officer recently observed, poor governance has meant that Taliban commanders “wield both the carrot and the stick in the minds of many Afghans.”

Although corruption in Afghanistan cannot be eliminated overnight, it could be significantly reduced, and even modest improvements in public accountability will substantially enhance the legitimacy of the new government. As Afghanistan seeks to stand on its own, the national unity government cannot afford to appear indifferent to the anger many Afghans feel toward an entrenched elite widely perceived to be motivated more by greed than by a spirit of public service. Likewise, the frustration of the American public over revelations of the massive scale of fraud and waste of U.S. taxpayer funds in Afghanistan must be considered.

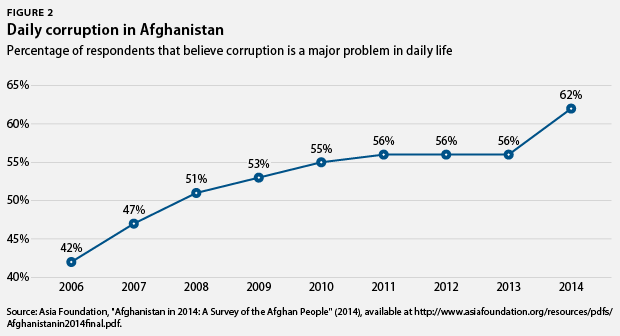

An epidemic of graft

Transparency International—an organization that assesses citizens’ views of endemic corruption—has consistently ranked Afghanistan as one of the top five most corrupt countries in the world, according to its Corruption Perceptions Index. According to a recent U.N. survey, half of Afghans reported paying a bribe in 2012; that figure was as high as 70 percent in some areas of the country. The same survey found that corruption was roughly tied with insecurity as the issue of greatest concern to Afghans, ahead of unemployment, standard of living, and even government performance as a general matter. Consistent with these findings, the U.S. Agency for International Development assessed in 2009 that corruption in Afghanistan “has become pervasive, entrenched, systemic, and by all accounts now unprecedented in scale and reach.” As recently as February, the U.S. Department of Defense Joint Chiefs of Staff wrote, “corruption alienates key elements of the population, discredits the government and security forces, undermines international support, subverts state functions and rule of law, robs the state of revenue, and creates barriers to economic growth.”

Widespread popular resentment of the various mujahideen warlords who governed the country in fiefdoms following the withdrawal of the Soviet Union facilitated the Taliban’s rise to power in the mid-1990s. The violence of the warlords fueled this resentment, but so did the graft and injustice that characterized their rule. The Taliban’s promise of swift and impartial rule-of-law resonated with much of Afghanistan’s population of the time—and continues to resonate for some Afghans today—despite its extreme brutality.

Corruption reemerged as a potent force in Afghan life following the U.S.-led international coalition’s overthrow of the Taliban in 2001. In the early years of the NATO mission in Afghanistan, a wide network of political elites connected to President Hamid Karzai effectively positioned themselves as intermediaries between well-intentioned Western officials, donors, and ordinary Afghans. The political elites succeeded in diverting billions of foreign aid dollars and investment to themselves and their allies, resulting in a number of high-profile scandals. The most disastrous of these was the near-collapse of the Afghan banking system following revelations that its largest institution, Kabul Bank, had essentially served as a ponzi scheme for a narrow clique tied to the Karzai government.

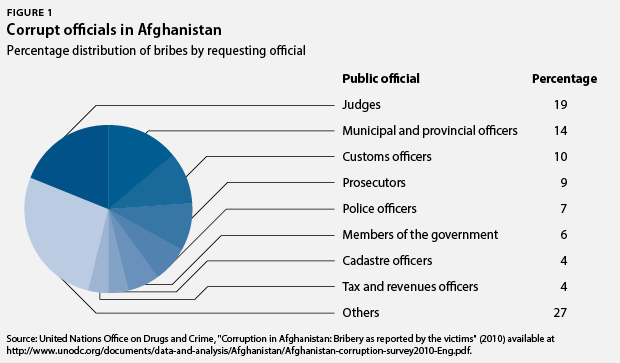

But the spread of corruption has not been confined to Afghanistan’s political upper echelon; it has pervaded virtually every aspect of government operations and the daily existence of citizens. According to the 2012 U.N. survey, approximately half of Afghans reported having paid a bribe to a teacher. Similar numbers of Afghans reported paying bribes to customs officials, judges, and prosecutors, and slightly less than half of survey respondents reported paying off land registry officials and provincial officers.

Entire government institutions have become enmeshed in complex patronage networks that stretch from minor functionaries to high-ranking ministers. Nowhere has this been more evident than in the realm of customs and border control. The New York Times recently reported, “corruption can no longer be described as a cancer on the system: It is the system.” A recent report by the Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction, or SIGAR, estimated that more than half of Afghanistan’s annual customs revenue is being lost to graft.

Perhaps most troubling, however—from the perspective of Afghanistan’s post-conflict transition—has been the persistent corruption that has plagued the organs of government directly responsible for law and order. The Afghan National Police, or ANP, have become particularly notorious for pernicious graft. SIGAR has repeatedly faulted the Afghan Ministry of the Interior for failing to properly account for billions of dollars allocated for police salaries via a U.N.-administered trust fund. According to SIGAR’s most recent audit report, corrupt practices within the ministry “could take as much as 50 [percent] of a policeman’s salary.” This underpayment has predictably resulted in a high incidence of corrupt solicitations by police officers, which affects ordinary Afghans most directly. A 2012 survey by the Asia Foundation found that more than half of Afghans who had contact with an ANP officer over the previous year were forced to pay a bribe.

The Afghan National Army, while more professional than the ANP, has also struggled with misallocation of resources and high incidences of bribe solicitation. A 2013 Transparency International survey found that one-fifth of Afghans viewed the military as corrupt. By contrast, the justice system may be even more reviled than the police—both the Transparency International and United Nations surveys found that Afghans consider judges the judiciary the most corrupt segment of their society.

Causes and effects of corruption

The causes of corruption in Afghanistan are numerous and complex. Decades of conflict have severely hampered the development and maintenance of effective government institutions and the civil organizations that monitor them. The country’s legislative and regulatory frameworks are patchwork and inconsistently enforced, and the agencies tasked with fighting corruption and imposing rule of law often work in isolation and contradict one another. Education levels are low; illiteracy is rampant among the ANP and ANSF. Civil servants are frequently underpaid, and they receive little training. After decades of war, officials use the opportunity of public office to fill personal coffers and channel funds to patronage networks at the expense of public good.

In Afghanistan and other countries with tribal systems and entrenched ethnic divisions, structural weaknesses interact in complex ways with traditional ideas about patronage and kinship—particularly with the expectation that those who have influence wield it to benefit members of their extended network. A recent assessment by the Joint and Coalition Operational Analysis, or JCOA, determined that corruption in Afghanistan was greatly exacerbated by the U.S. government’s “initial support of warlords, [and] reliance on logistics contracting,” coupled with the lack of understanding by U.S. and coalition officials of the scale or nature of Afghan corruption.

In the immediate response to the attacks of September 11, the United States utilized existing patronage networks and local warlords to defeat the Taliban and Al Qaeda. Similarly, President Karzai placed warlords in key government positions when he took office to obtain loyalty and sustain political power. According to JCOA, “Once ensconced within ministries and other government posts, the warlords-cum-ministers often used their positions to divert [Afghan government resources] to their constituencies,” and thus embedded corruption within the new democratic system. A recent World Bank report observed that expectations of reciprocal patronage entrenched in Afghan society have led to “constant attempts to interfere with standard merit-based appointment processes by members of the government, the President’s office, members of Parliament, individual commanders, and influential political personalities of all origins.”

These conditions would likely produce significant levels of corruption under any circumstances. In Afghanistan, however, their effects have been amplified by two factors unique to country’s troubled history: a massive influx of foreign assistance—often distributed without proper monitoring mechanisms and which quickly exceeds the absorptive capacity of the Afghan government—and a resurgent narcotics trade, which has a warping effect on the Afghan economy that is hard to overstate.

With respect to foreign assistance, the United States alone contributed more than $73 billion in economic and military assistance to Afghanistan between 2002 and 2012. According to the World Bank, foreign aid and spending by foreign troops accounted for 97 percent of Afghanistan’s gross domestic product, or GDP, in 2012. The World Bank has also estimated that 70 percent of overall public spending in Afghanistan occurs outside the formal government budget. Yet corruption has directly undermined the efforts of the international community—above all, the United States—to arm and train Afghan policeman and soldiers. Last year, a SIGAR audit found incomplete tracking information for more than 200,000 weapons that the U.S. Department of Defense had provided for the Afghan National Security Forces, or ANSF, which encompasses both the police and military forces.

Cash flows of such a significant magnitude would pose monitoring challenges for even the most scrupulous of donors and absorptive capacity issues for even the most effective governments. For many years, however, the United States and other major reconstruction partners demonstrated little ability to track—or interest in tracking—the ultimate use of their funds. Security constraints on both military and civilian officials prohibited effective monitoring, evaluation of projects, and spending oversight. As a result, a culture of dependence arose in which the government relied on subcontractors to implement and deliver needed programs and supplies. “Compounding the problem … [of corruption], the international community exercised only limited oversight of its spending due to poor security environment. This was further exacerbated by the community members’ unwillingness to place conditions on the provision of their aid,” according to JCOA.

Even today, oversight of contractors, who received an estimated $37 billion to assist in reconstruction efforts between 2002 and 2013, is marred by poor coordination and widespread lack of compliance with rules and standards. In testimony submitted on February 25 to the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, John F. Sopko, the special inspector general for Afghanistan Reconstruction, stated that “more than $50 billion in U.S. assistance had been provided for reconstruction in Afghanistan since 2002 without the benefit of a comprehensive anti-corruption strategy, and that U.S. anticorruption efforts had provided relatively little assistance to some key Afghan institutions.”

Furthermore, pressure from donors to spend quickly in the face of a growing insurgency, especially after 2009, meant that funds were spent first and questions posed later. Such a process led to SIGAR’s finding that U.S. Agency for International Development, or USAID, funds ended up in the hands of Taliban fighters running a construction firm and with Afghan contractors beholden to provincial governors or provincial council chairman, such as Karzai’s half-brother Ahmed Wali Karzai. Local Afghans, meanwhile, heard lofty development goals only to see foreign-assistance funds channeled to the very people who controlled the system.

Time to implement and enhance support for anticorruption efforts

Without political will, no country can effectively fight corruption, or even win the battle to stem corruption in the short term. In Afghanistan, such political will was lacking during the presidency of Hamid Karzai. If there is a silver lining to the otherwise dismal record of the Afghan government on corruption issues, it is that the new administration has announced that the fight against graft is among its top priorities.

Both President Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah declared their intention to clean up government during their campaigns. In an encouraging sign, Ghani reopened an inquiry into embezzlement at Kabul Bank days after assuming office. But setting Afghanistan on a path toward more effective and accountable governance will require far more than high-profile prosecutions. Afghan citizens want to see government officials take visible actions to crack down on corruption at all levels.

Afghanistan has passed several legislative measures aimed at tackling corruption. For instance, in 2008, the government ratified the U.N. Convention against Corruption, and President Karzai issued a decree establishing the High Office for Oversight and Anti-Corruption, or HOO. The office is responsible for the coordination and monitoring the implementation of Afghanistan’s anticorruption strategy, as well as administrative procedural reform in the country.

But passing legislation and ratifying treaties only goes so far; efforts now need to focus on implementing these measures and enforcing the law. The good news is that numerous other countries have grappled with the issue of corruption, producing an abundance of lessons learned and best practices. The national unity government should begin to leverage the vast knowledge gleaned from anticorruption initiatives in other countries to establish mechanisms that can expedite efforts in Afghanistan. International donors and civil society organizations should prioritize assistance and training efforts focused on bolstering Afghan anticorruption efforts.

However, given the vast scale of corruption and urgent need for reform, the most daunting task may be determining where to start and which areas to prioritize in the short term. This is critical for demonstrating to both donors and Afghan citizens that the promise to fight corruption is real and not just political rhetoric. The following recommendations—presented for consideration by Afghan and U.S. officials—offer a starting point in the fight against corruption.

Recommendations

Send a clear signal from the top down

Political will is essential to fight corruption. President Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah should show the public that they are serious about prioritizing efforts to stem graft and illicit acts through public office by signing an integrity pledge and requiring all ministers and cabinet officials to sign it as well. A pledge making clear that corruption, bribes, graft, and ill-gotten monetary gains will not be tolerated would signal a new way of doing business for the Afghan government. Such a pledge would provide symbolic value for the citizenry, but it would carry even more meaning if it were tied to enforceable provisions in Afghanistan law such as anti-bribery measures and anti-money laundering statutes. An integrity pledge could help to restore some level of faith in the elected officials and begin the process of rebuilding the government’s reputation. Furthermore, top-level action will signal to lower-level officials and civil servants that anticorruption efforts will be taken seriously in the national unity government.

Prioritize efforts to combat money laundering and terrorism finance

Given the vast, illicit nature of trade and smuggling in Afghanistan and the huge vulnerabilities created by corruption, as well as the weakness of the criminal justice system, Afghan officials should prioritize efforts to create an effective system to combat money laundering and terrorism finance. The International Monetary Fund, or IMF, conducted a mutual evaluation on behalf of the Financial Action Task Force, or FATF, to assess Afghanistan’s compliance with international norms in regulating money laundering and terrorism finance. The 2010 collapse of Kabul Bank should have prompted stricter regulation of currency flow within the country—certainly when money changed hands in large quantities. Yet the FATF report noted that “in spite of the vast illicit sector and corruption issues that plague Afghanistan and the risks associated with them, the authorities were relatively unresponsive on the subject of how this may impact the implementation of the [anti-money laundering/ countering terrorism finance] regime.”

Similarly, in October 2014, the Independent Joint Anti-Corruption Monitoring and Evaluation Committee, a collaborative oversight effort made up of Afghan national and international experts, noted that significant gaps remain in basic oversight mechanisms, which are critical to prevent another banking scandal and to seek punitive steps for those responsible for stealing the funds. As the committee’s latest report notes, “sincere effort is needed to resolve outstanding Kabul Bank issues and the change in government could provide the required political will. To do so would demonstrate the new government’s commitment to ending impunity, act as a deterrence, increase recoveries, and address structural weaknesses that permeate public administration.”

In a positive step, President Ghani has reopened the investigation into the Kabul Bank scandal and started anew attempts to recoup the nearly $1 billion in stolen assets. Mahmoud Karzai, the brother of former President Karzai, has been implicated in the scandal and is doing little to cooperate with the investigation. To guard against future scandals, the new government must prioritize legislation to effectively criminalize money laundering and terrorist financing; to create a legal framework for identifying, tracing, and freezing terrorist financing; and to establish and implement broad procedures for the confiscation of assets related to corruption and money laundering. As the FATF noted in 2011, “there was little understanding of the importance of the effective implementation of the [anti-money laundering/ countering terrorism finance] regime to overall governance and the rule of law, and conversely, the criticality of the rule of law to economic development and financial integrity.” Realizing this connection, it is essential that the Afghan government end the impunity that corrupt actors use to obtain and move the proceeds of their corruption.

Increase participation of civil society

Afghanistan has a nascent but growing base of domestic civil-society organizations, as well as a plethora of international civil-society organizations, that are working on behalf of Afghans. Civil society can serve as a watchdog for the public interest and provide both formal and informal checks on corrupt behavior and illicit spending of public funds. Given the entrenched corruption endemic at all levels of the Afghan government, Afghan leaders should consider the ability of both domestic and international civil-society organizations to scrutinize information and contribute to monitoring government accountability an especially valuable tool.

Afghanistan should immediately consider joining the Open Government Partnership, or OGP. Founded in 2011, OGP is a multilateral initiative founded on the premise of collaboration between government and civil society to promote transparency, fight corruption, and utilize new technologies to strengthen governance. OGP provides a framework for country-specific actions coupled with a supportive platform to leverage expertise from other countries and international organizations. Afghanistan would greatly benefit from these peer-to-peer learning mechanisms, as well as the support provided by international experts. OGP has grown to 65 participating countries, representing one-third of the world’s population and more than 1,000 open government reform commitments.

OGP provides a framework enabling those withingovernment, the private sector, and civil society to advance government accountability and effectiveness. Each participating country must commit to jointly develop and implement a national action plan in collaboration with civil society. Afghanistan is currently very close to meeting the requirements for eligibility in OGP and could be reviewed again based on the recently enacted Access to Information Bill. The new legislation—signed by President Ghani in December 2014—is unprecedented in Afghan history and will provide citizens and journalists with more transparent access to state institutions.

Utilize technology

Honest government will only come about when ordinary citizens demand it. Afghan citizens want to see change and technology could provide a huge boost to anticorruption efforts in the country. Efforts should be made to create platforms on social media and through other forms of technology for anticorruption activism and public-private partnerships. Afghanistan has a cell phone penetration rate of 71 per 100 people, and Internet service is rapidly expanding.

In countries around the globe, citizens are using cellphones, social media, and the Internet to shine a light on corrupt acts and officials. People can anonymously report who is being asked to pay a bribe, absenteeism in schools and hospitals, extortion by government officials, failures to deliver services, corruption in contracting or the delivery of school supplies or drugs, and election irregularities. Websites such as Ipaidabribe.com in India and similar efforts in Kenya, Estonia, Guatemala, Columbia, and numerous other countries are incentivizing change and supporting governmental efforts to instill change. Similarly, many websites allow citizens to report when they did not pay a bribe in order to reinforce the honest efforts of public servants and support for good governance.

Expand training on corruption to military, police, and judiciary

There is no quick fix to stem corruption in Afghanistan. Training efforts have been underway by the United States and other donors for several years and are currently transitioning to Afghan-led training. These Afghan efforts should be expanded and continue to build on international training standards. Both President Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah have pledged to remove corrupt ANSF officials and to promote only based on merit. They have made a first move in Herat by removing two ANP officials accused of corruption. Accusations are one thing—and should be weighed carefully given their potential to settle other grievances—but President Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah need real, hard proof in order to prosecute corrupt ANSF officials. Reviving the Major Crimes Task Forces, the work of the Sensitive Investigative Unit, and the Technical Investigative Unit would create Afghan government offices capable of building a legal case against ANSF corruption.

Corruption diminishes the ability of the Afghan police and military to maintain law and order and protect the Afghan people from violent insurgency. The U.S. government has assessed that corruption has eroded public confidence in the military and police and is a “key factor undermining developmental progress and morale at the unit level.” The New York Times reported in February that the government of Afghanistan was engaged in “one of the most significant corruption investigations of the national police force in years” in connection with intelligence indicating that police officers in Kunduz had been collaborating with the Taliban.

Similarly, frustration with corruption in the federal judicial system has led many Afghans to turn to Taliban courts as a fast and impartial means of resolving disputes—a disturbing echo of the conditions proceeding the Taliban conquest of Afghanistan in the 1990s. As Integrity Watch Afghanistan observed in a recent report, “the ability of any state to deliver justice … [is] an important indicator of its capacity” to govern. On this issue, the Taliban appears to have a better record of performance than the national government in the eyes of many Afghans.

Improve transparency in procurement and extractives sector

Afghanistan’s vast mineral wealth is estimated at nearly $1 trillion and remains largely unexploited. The few mining operations that do exist have been predictably tainted with allegations of widespread irregularity and influence peddling. Government oversight of mineral resource extraction is paltry to nonexistent, and a new mining law threatens to exacerbate this situation. With the support of the World Bank and other donors, however, Afghanistan is participating in the Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative, which provides a framework for monitoring of the sector in collaboration with the private sector and civil society.

Several groups—including Global Witness, a leading international nongovernmental organization active in this area—have conducted additional research and analysis on how to avoid the so-called resource curse, curb corruption, and improve oversight in Afghanistan. While the vast mineral and oil wealth in Afghanistan may provide an economic lifeline for growth and development, the more likely scenario is that mining will further exacerbate corruption. President Ghani has recognized the need to prioritize reforms in the mining sector and has promised a patient approach, but significant support is needed from donors.

Until effective oversight and legislative measures are established to ensure an open tendering processes and transparency for contracting and supply chains, Afghanistan’s best protection against further corruption in the sector is to leave the minerals in the ground and preserve its mineral wealth for the future. In the near term, the United States and other donors must prioritize capacity building and technical assistance to the Ministry of Mines, as well as to Afghan parliamentarians with oversight of the extractives sector, to ensure that future tendering of projects and legislation regulating the mining sector contains effective oversight mechanisms.

Implementation of the open contracting initiative may be an effective tool to prioritize in the short term. Governments routinely sign trillions of dollars worth of contracts for services and infrastructure projects, but rarely do government officials or citizens know what a particular contracted company is responsible for delivering. Afghanistan is no different and would benefit from increasing disclosure and participation in all stages of public contracting, as well as from open contracting efforts that zero in on tendering, performance, and contract implementation.

Identify ways the United States and international community can assist anticorruption efforts

The United States and the international donor community should encourage and support Afghanistan in its efforts to effectively take on the challenge of corruption while maintaining realistic expectations about the likely pace of progress. It is critically important that leadership of the fight against corruption remains firmly in the Afghan government’s hands, with strong support from international partners. Efforts are needed create a high-level and public dialogue on corruption and the continuation of technical assistance and capacity building is essential. However, the international community could better coordinate assistance to ensure that all needs are addressed and that multiple donors are not providing repetitive, or even contradictory, advice on measures to be taken in the fight against corruption.

The United States and the international community could also revolutionize efforts aimed at enhancing Afghan governmental transparency and accountability by ensuring that all contracts with the government at national and subnational levels are publicly available. Injecting transparency into Afghanistan’s own programs could yield faster results and greater benefits. For example, disclosure of bid requests and contract awards and of audited financial accounts, in parallel with the similar actions undertaken by the Afghan government, would allow for better accountability and oversight. Efforts by the United States and the international community to ensure such transparency would have positive demonstrative effect and place an emphasis on good governance.

Conclusion

As recently as January 2015, SIGAR asserted that the United States “lacks a comprehensive anti-corruption strategy” for Afghanistan. Given the vast amount of foreign assistance and resources that the United States devotes to Afghanistan, this must change. The United States needs to prioritize efforts to support Afghanistan’s anticorruption capacity and to assist with developing accountability mechanisms for the government. Most importantly, U.S. officials should support the development and implementation of a comprehensive Afghan anticorruption strategy. Efforts to stem corruption in the country will only be successful when the political leaders in Afghanistan demand change and lead such change.

Corruption is a grave threat to the viability of the Afghan state and to U.S. policy objectives in Afghanistan. Corruption deprives the Afghan people of the benefits of fair and effective governance at the most basic level, which in turn diminishes the legitimacy of the state and the loyalty it commands among the general population. The time to turn the tide and set Afghanistan on a better path to good governance is now. If another Afghan administration fails to tackle the problem of corruption, there may never be another opportunity to do so.

Mary Beth Goodman is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress and a Senior Advisor to the Enough Project. She previously served as the director for international economics at the White House and as a diplomat for the U.S. Department of State. Trevor Sutton is a graduate of Yale Law School and a former fellow in the Office of the Secretary of Defense. He is currently a consultant to the United Nations.