Imagine that tomorrow, while cleaning out your gutters, you fall off a ladder. You suffer a traumatic brain injury and spinal cord damage, leaving you paralyzed, unable to speak, and with significantly impaired short- and long-term memory. Unable to work for the foreseeable future, you have no idea how you are going to support your family. Now imagine your relief when you realize an insurance policy you have been paying into all your working life will help keep you and your family afloat by replacing a portion of your lost wages. Fortunately, there is no need to conjure up the source of your relief: it is our Social Security system.

Overview

Social Security Disability Insurance has been a core pillar of our nation’s Social Security system for nearly six decades, offering critical protection when Americans need it most. Today, it protects more than 9 out of 10 American workers and their families in the event of a life-changing disability or illness that prevents substantial work. While it may not be easy to think about, a young worker starting a career today has a one-in-three chance of either dying or needing to turn to Disability Insurance before reaching his or her full Social Security retirement age of 67. In other words, Social Security Disability Insurance provides basic but essential protection.

While benefits are modest, averaging just $1,140 per month, Social Security Disability Insurance plays a significant role in boosting economic security for beneficiaries, and for 8 out of 10 beneficiaries it is their main or only source of income. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, the program’s eligibility criteria are among the strictest in the world, and only individuals with the most significant disabilities and severe illnesses qualify. Most applicants are denied benefits, and fewer than 4 in 10 are approved. Many beneficiaries have multiple impairments, and many are terminally ill: nearly one in five die within five years of receiving benefits.

As expected, the program has grown in recent years as a result of well-understood demographic and labor-market changes: Baby Boomers aging into their high-disability years, the increase in women’s labor-force participation, and population growth. The growth of the program has leveled off and is projected to decline further in the coming years as Baby Boomers retire. While the Disability Insurance trust fund currently faces a financing shortfall, rebalancing the two Social Security trust funds will put the entire Social Security system on sound footing until 2033. Rebalancing has served as routine housekeeping to keep both trust funds on sound footing amid demographic shifts and has occurred 11 times in the program’s history, about equally in both directions. Several policy options exist to ensure the long-term solvency of the overall Social Security system thereafter.

Social Security Disability Insurance provides vital protection to nearly all American workers and their families

Social Security was established nearly 80 years ago to ensure “the security of the men, women and children of the nation against the hazards and vicissitudes of life.” In 1956, the program was expanded to include Disability Insurance in recognition that the private market for long-term disability insurance was failing to provide adequate or affordable protection to workers.

Today, nearly all Americans—91 percent of workers ages 21 to 64—are protected by Social Security Disability Insurance. In all, more than 160 million American workers and their families are protected. About 8.9 million disabled workers—including more than 1 million veterans—receive Disability Insurance benefits, as well as about 157,000 spouses and 1.9 million dependent children of disabled workers.

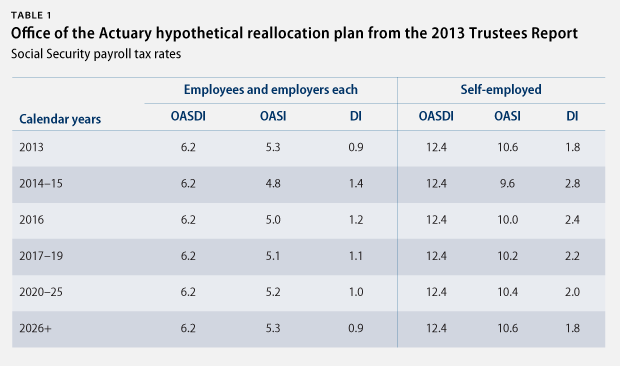

Social Security Disability Insurance is coverage that workers earn

For a young worker with a spouse, two children, and average earnings, the value of the coverage that Disability Insurance provides is equivalent to a $580,000 insurance policy, and many estimates suggest that the real value of the protection it offers is much higher. Both workers and employers pay for Social Security through payroll tax contributions. Workers currently pay 6.2 percent of the first $117,000 of their earnings each year, and employers pay the same amount up to the same cap. Of that 6.2 percent, 5.3 percent currently goes to the Old Age and Survivors Insurance, or OASI, trust fund, and 0.9 percent to the Disability Insurance trust fund. Due to the interrelatedness of the Social Security programs, the two funds are typically considered together, although they are technically separate. The portion of payroll tax contributions that goes into each trust fund has changed several times throughout the years to account for demographic shifts and the funds’ respective projected solvency.

Benefits are modest but vital to economic security

The amount a qualifying worker receives in benefits is based on his or her prior earnings.Benefits are modest, typically replacing about half or less of a worker’s earnings. The average benefit is about $1,140 per month—not far above the federal poverty line.

For more than 80 percent of beneficiaries, Disability Insurance is their main source of income. For one-third, it is their only source of income. Benefits are so modest that many beneficiaries struggle to make ends meet; nearly one in five, or about 1.6 million, disabled-worker beneficiaries live in poverty. But without Disability Insurance, this figure would more than double, and more than 4 million beneficiaries would be poor.

Workers who receive Disability Insurance are also eligible for Medicare after a two-year waiting period.

Social Security Disability Insurance provides protection most of us could never afford on the private market

Just one in three private-sector workers has employer-provided long-term disability insurance, and plans are often less adequate than Social Security. Coverage is especially scarce for low-wage workers—just 7 percent of workers making less than $12 an hour have employer-provided disability insurance. Workers in industries such as retail, hospitality, and construction are among the least likely to have employer-provided longterm disability coverage, and coverage is highly concentrated among white-collar professions. Access is even more limited on the individual market. While it is difficult to compare Disability Insurance with private long-term disability plans given that private plans often exclude certain types of impairments—as well as workers with pre-existing conditions or in high-risk occupations—purchasing a plan of comparable value and adequacy on the individual private market would be unrealistic for most Americans.

Eligibility criteria are stringent and most applicants are denied

Social Security Disability Insurance is reserved for workers whose disabilities or illnesses are so debilitating that they cannot support themselves through work. Under the Social Security Act, the eligibility standard requires that a disabled worker be “unable to engage in substantial gainful activity”—defined as earning $1,070 per month, for 2014—“by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.” In order to meet this rigorous standard, a worker must not only be unable to do his or her past jobs, but also—considering his or her age, education, and experience—any other job that exists in significant numbers in the national economy at a level where he or she could earn even $270 per week.

A worker must also have earned coverage in order to be protected by Disability Insurance. A worker must have worked at least one-fourth of his or her adult years, including at least 5 of the 10 years before the disability began in order to be “insured.”

Comparing disability benefit systems, the OECD describes the United States—along with South Korea, Japan, and Canada—as having “the most stringent eligibility criteria for a full disability benefit, including the most rigid reference to all jobs available in the labor market.”

In practice, proving medical eligibility for Disability Insurance requires extensive medical evidence from one or more “acceptable medical sources”—licensed physicians, specialists, or other approved medical providers—documenting the applicant’s severe impairment, or impairments, and resulting symptoms. Evidence from other providers, such as nurse practitioners or clinical social workers, is not enough to document a worker’s medical condition. Statements from friends, loved ones, and the applicant are not considered medical evidence and are not sufficient to establish eligibility.

Most claims for Disability Insurance are denied under this stringent standard. Nearly 80 percent of applicants are denied at the initial level, and fewer than 4 in 10 are approved after all levels of appeal. Underscoring the strictness of the disability standard, thousands of applicants die each year while waiting for benefits. And one in five male and nearly one in six female beneficiaries die within five years of being approved for benefits. Disability Insurance beneficiaries have death rates three to six times higher than other people their age.

Beneficiaries have a wide range of significant disabilities and debilitating illnesses and many have multiple impairments

Disabled workers who receive Disability Insurance live with a diverse range of severe impairments. The Social Security Administration categorizes beneficiaries according to their “primary diagnosis,” or main health condition. As of 2012, the most recent year for which impairment data are available:

- 31.8 percent have a “primary diagnosis” of a mental impairment, including 4.2 percent with intellectual disabilities and 27.6 percent with other types of mental disorders such as schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, or severe depression.

- 29.8 percent have a musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorder.

- 8.7 percent have a cardiovascular condition such as chronic heart failure.

- 9.3 percent have a disorder of the nervous system, such as cerebral palsy or multiple sclerosis, or a sensory impairment such as deafness or blindness.

- 20.4 percent include workers living with cancers; infectious diseases; injuries; genitourinary impairments such as end stage renal disease; congenital disorders; metabolic and endocrine diseases such as diabetes; diseases of the respiratory system; and diseases of other body systems

A fact not well captured by Social Security’s data—given that beneficiaries are categorized by “primary diagnosis”—is that many beneficiaries have multiple serious health conditions. For instance, nearly half of individuals with mental disorders have more than one mental illness, such as major depressive disorder and a severe anxiety disorder. Individuals with mental illness are also at greater risk of poor physical health: The two leading causes of death for individuals with mental illness are cardiovascular disease and cancers. Musculoskeletal disorders commonly afflict multiple joints, and individuals with musculoskeletal impairments—typically older workers whose bodies have broken down with age—commonly suffer additional health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and respiratory disease.

The breakdown of impairment categories among Disability Insurance beneficiaries is consistent with global health trends. According to the World Health Organization, the leading causes of disability today in most regions of the world—including the United States—are musculoskeletal impairments and mental disorders. The rise in mental impairments around the world is often attributed to increased awareness and reduced stigma of mental illness. And the global rise in musculoskeletal impairments is attributable to the aging of the population both in the United States and around the world—since the risk of experiencing musculoskeletal impairments rises sharply with age—as well as to the drop in mortality.

Most beneficiaries of Disability Insurance are older and had physically demanding occupations

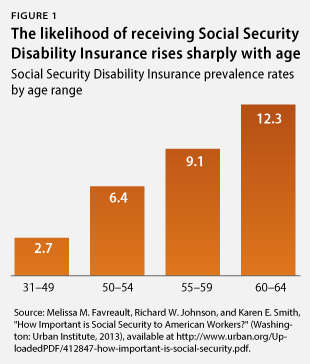

Most beneficiaries of Disability Insurance—7 in 10—are in their 50s and 60s, and the average age is 53. The fact that most beneficiaries are older is unsurprising given that the likelihood of disability increases sharply with age: a worker is twice as likely to experience disability at age 50 than at 40, and twice as likely at 60 than at 50. Before turning to Social Security, most disabled-worker beneficiaries worked at “unskilled” or “semiskilled” physically demanding jobs. About half—53 percent—of disabled workers who receive Disability Insurance have a high school diploma or less. About one-third completed some college, and the remaining 18 percent completed four years of college or have further higher education.

Few beneficiaries are able to support themselves through work

Disability Insurance beneficiaries are permitted to work while receiving benefits. They may earn up to the substantial gainful activity level—$1,070 per month in 2014—with no effect on their monthly benefits. However, given how strict the Social Security disability standard is, most beneficiaries live with such debilitating impairments and health conditions that they are unable to work at all and most do not have earnings. According to a recent study linking Social Security data and earnings records before the onset of the Great Recession, in 2007, it was found that fewer than one in six, or 15 percent, of beneficiaries had earnings of even $1,000 during the year. The vast majority of those who worked earned very little, and just 3.9 percent earned more than $10,000 during the year—hardly enough to support oneself.

Further underscoring the strictness of the Social Security disability standard, even disabled workers who are denied benefits exhibit extremely low work capacity afterward. A recent study of workers denied Disability Insurance benefits found that just one in four were able to earn more than the substantial gainful activity level post-denial.

For those whose conditions improve and who wish to test their capacity to work, Social Security Administration policies include strong work incentives and supports.Beneficiaries whose conditions improve enough that they are able to earn more than the substantial gainful activity level are encouraged to work as much as they are able to and may earn an unlimited amount for up to 12 months without losing a dollar in benefits. Those who work above the substantial gainful activity level for more than 12 months enter a three-year “extended period of eligibility,” during which they receive a benefit only in the months in which they earn less the substantial gainful activity level. After the extended period of eligibility ends, if at any point in the next five years their condition worsens and they are not able to continue working above that level, they can return to benefits almost immediately through a process called “expedited reinstatement.” This process allows them restart their needed benefits without having to repeat the entire, lengthy disability-determination process. These policies are extremely helpful to beneficiaries with episodic symptoms or whose conditions improve over time.

How does the United States compare with other countries

- The Social Security disability standard is among the strictest in the world. The OECD describes the U.S. disability benefit system, along with those of Canada, Japan, and South Korea, as having “the most stringent eligibility criteria for a full disability benefit, including the most rigid reference to all jobs in the labor market.”

- Social Security Disability Insurance benefits are less generous than most other countries’ disability benefit programs. With Disability Insurance benefits replacing 42 percent of prior earnings for the median earner, the United States is ranked 30th out of 34 OECD member countries in terms of replacement rates. Many countries’ disability benefit programs replace 80 percent or more of prior earnings.

- By international standards, the United States spends comparatively little on disability benefits. In 2009, U.S. spending on Social Security Disability Insurance equaled 0.8 percent of gross domestic product, or GDP—again putting the United States near the bottom at 27th out of 34 OECD member countries in spending on equivalent programs. On average, OECD member countries spend 1.2 percent of GDP on their equivalent programs, and many—such as Denmark (2 percent), the United Kingdom (2.4 percent) and Norway (2.6 percent)—spend significantly more.

- The share of the U.S. working-age population receiving Disability Insurance benefits— about 6 percent—is roughly on par with the OECD average of 5.9 percent.

- In drawing international comparisons, it is well worth noting that in addition to more generous disability benefit systems with less rigorous eligibility standards, European nations tend to have universal paid leave policies, more generous health care systems, higher levels of social spending generally, and more regulated labor markets than the United States.

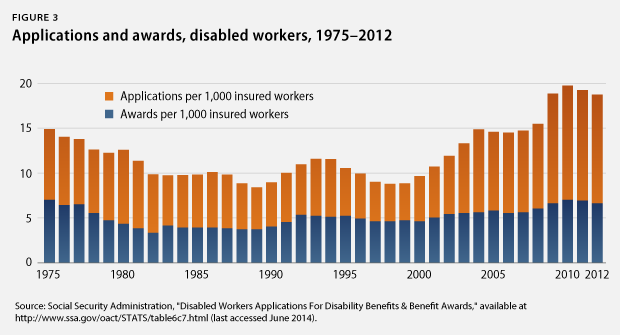

Growth is mostly due to demographic changes and is leveling off

As long projected by Social Security’s actuaries, the number of workers receiving Social Security Disability Insurance has increased over time, due mostly to demographic and labor-market shifts. According to a recent analysis by Social Security Administration researchers, the growth in the program between 1972 and 2008 is due almost entirely—at 90 percent—to the Baby Boomers aging into the high-disability years of their 50s and 60s, the rise in women’s labor-force participation, and population growth. Importantly, as Baby Boomers retire, the program’s growth has already leveled off and is projected to decline further in the coming years. Due to the importance of these demographic factors, Social Security’s actuaries analyze trends in benefit receipt using the “age-sex adjusted disability prevalence rate,” which controls for changes in the age and sex distribution of the insured population, as well as population growth. The age-sex adjusted disability prevalence rate was 4.6 percent in 2013 compared to 3.1 percent in 1980.

Key drivers of the program’s growth include:

- Aging population: The risk of disability increases sharply with age. A worker is twice as likely to be disabled at age 50 than at 40, and again twice as likely at age 60 than at 50. Born between 1946 and 1964, Baby Boomers have now aged into their high disability years, driving much of the growth in Disability Insurance.

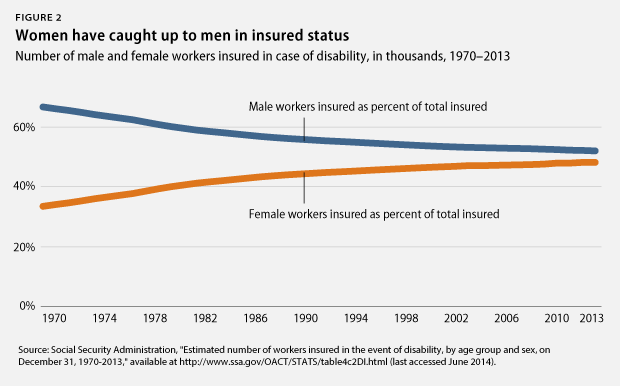

- Increase in women’s labor-force participation: Whereas previous generations of women had not worked enough to be insured in case of disability, women today have essentially caught up with men when it comes to being insured for benefits based on their work history.

- Population growth: The working-age population—ages 20 to 64—has grown significantly, by 43 percent between 1980 and 2013.61 The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that population growth alone—even if the population were not aging—would have resulted in an additional 1.25 million beneficiaries in 2013 compared with 1980.

- Women’s catch-up in rates of receipt: Just as women have caught up with men in terms of having worked enough to be insured for Disability Insurance, the gender gap in rates of receipt of benefits has closed as well. As recently as 1990, male workers outnumbered female workers by 2-to-1, whereas today, nearly 48 percent of workers receiving Disability Insurance are women.

- Increase in Social Security retirement age: The increase in the Social Security retirement age from 65 to 67 has played a role as well, as disabled workers continue receiving Social Security Disability Insurance for longer before converting to retirement benefits when they reach full retirement age. About 5 percent of Social Security Disability Insurance beneficiaries are ages 65 and 66.

Routine action is needed to address finances

As the Baby Boom generation retires, the growth in Disability Insurance has already leveled off and is projected to decline further. Social Security’s actuaries have projected since the mid-1990s that the Disability Insurance trust fund would be able to pay all scheduled benefits until 2016, at which point action would be needed to shore up the fund. Absent needed action, the Disability Insurance trust fund will be able to pay 80 percent of promised benefits after 2016.

While the OASI fund and the Disability Insurance fund are technically separate, they are typically considered together due to the interrelatedness of Social Security’s programs. For example, Social Security’s programs share the same benefit formula, beneficiaries regularly move between programs, and changes to one program—such as raising the retirement age—affect both trust funds. Since Social Security Disability Insurance was established in 1956, Congress has repeatedly, on a bipartisan basis, rebalanced the OASI and Disability Insurance trust funds to keep both on sound footing amid changing demographics. Rebalancing—by reallocating the share of payroll tax contributions that go into each fund—has occurred 11 times over the years, roughly equally in both directions.

Congress has never allowed a drop in scheduled benefits to occur. Congress could again enact a modest, temporary reallocation of the 6.2 percent payroll tax rate between OASI and Disability Insurance to equalize the solvency of the two funds. The reallocation plan outlined by Social Security’s chief actuary in the 2013 Trustees Report would ensure that both funds remain fully solvent until 2033. Reallocation would have essentially no impact on the financial health of the overall Social Security system. Under current law, as well as under reallocation, the combined trust funds will be able to pay all scheduled benefits until 2033, after which they will be able to pay about 77 percent of promised benefits.

While the combined trust funds are set to remain on sound footing for the next two decades, action will be needed sometime during that time period to ensure the long-term solvency of the overall Social Security system. But in the near term, as Secretary of the Treasury Jacob Lew noted in testimony before the Senate Budget Committee, “There is only one solution the technical experts believe can work in the timeframe between now and 2016. And that’s a reallocation of the tax rate, as we’ve done in the past.”

Looking past 2016, there are a number of options for ensuring the long-term solvency of the overall Social Security system without cutting already modest benefits—something that polls consistently confirm most Americans oppose. Frequently discussed policy options include modestly increasing the 6.2 percent payroll tax rate that workers and employers each pay and eliminating the cap on earnings that are subject to payroll taxes so that the 5 percent of workers who earn more than the cap would pay into the system all year as other workers do. A recent survey conducted by the nonpartisan National Academy of Social Insurance found overwhelming support for a reform package that includes both of these options while also boosting benefits. An array of legislation introduced within the past two years has included variations of these reforms, reflecting their growing popularity.

Conclusion

Social Security Disability Insurance has been a core pillar of our nation’s Social Security system for nearly six decades, offering critical protection to nearly all American workers and their families in the event of a life-changing disability or illness. It is a lifeline to millions of Americans, providing critical economic security when it is needed most. Congress has many options to ensure long-term solvency of the overall Social Security system over the next 20 years. In the meantime, rebalancing the OASI and Disability Insurance trust funds—as has been done 11 times in the program’s history—would ensure that Social Security is able to pay all promised retirement, disability, and survivor benefits for the next two decades.

Rebecca Vallas is the Associate Director of the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress. Shawn Fremstad is a Senior Fellow at the Center and a senior research associate at the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C.