In the wake of Turkey’s June 24 presidential and parliamentary elections, Ankara has undertaken a coordinated campaign aimed at rejuvenating ties with the European Union in the face of a dramatic downturn in the Turkish economy. Turkish-European relations had grown strained in recent years over Turkey’s stalled accession process to join the bloc, as well as the country’s authoritarian drift, sweeping crackdown on dissent, management of the migration crisis, and the cases of EU citizens held in Turkish prison on what European governments considered trumped-up charges.1 Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan took repeated rhetorical shots at European leaders in 2016 and 2017,2 even suggesting German Chancellor Angela Merkel exhibited “Nazism” for saying that Turkey’s EU accession bid could be reconsidered in light of the deteriorating human rights situation.3 While President Erdoğan’s attacks may have reflected his real animus at perceived European abandonment of Turkey in the face of regional crises and a stalled EU accession process, they were also likely aimed at mobilizing and uniting domestic constituencies with deeply anti-Western views.4

But with the end of the election season and a rapid deterioration of the Turkish economy, the focus has now shifted to restoring ties with Europe. Europe is Turkey’s most important trade and investment partner, and the Turkish charm offensive is motivated by the country’s economic crisis and the crash in the value of the Turkish lira, as well as by faltering ties with the United States.5 The lira’s free fall has brought Turkey’s reliance on external financing into stark relief and even raised the possibility of an embarrassing turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or European Bank for Reconstruction and Development for financial assistance. Turning to the IMF would be a bitter pill for Erdoğan, who seeks to project an image of Turkey as strong, economically self-sufficient, and independent from outside influence. The Trump administration’s tough line on Turkey for the ongoing detention of U.S. citizens—including largely symbolic sanctions on two Turkish cabinet ministers in line with the Global Magnitsky Act and new steel and aluminum tariffs under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act6—has cast another cloud over the Turkish economy and further underlined the necessity of patching up relations with the Europeans.

In light of this situation, CAP thought it useful to offer insights stemming from its recent nationwide polling of Turks, shedding light on public attitudes toward the European Union and the political dynamics shaping the Turkish government’s approach.7 The nationwide survey was conducted by Metropoll from May 24 to June 4, 2018, and is based on 2,534 face-to-face interviews in 28 provinces. The overall results on each question have a margin of error of 1.95 percent.

Like all public opinion surveys, the material presented here is only a snapshot. Moreover, it is a snapshot taken prior to the June 24 elections and further economic deterioration, both of which could somewhat alter the results were the questions asked today. Nevertheless, taken together with other data, these results underscore trends that persist to this day and are likely to continue for some time.

The survey shows deep ambivalence among Turks toward the European Union across party lines, with less than half of Turks saying they want the country to be part of the European Union.8 The Turkish public feels Europe does not want them; just 20 percent think European governments want Turkey in the European Union. Still, the European Union is attractive, and nearly two-thirds of Turks would like to travel, study, or work there. Just 8 percent of Turks feel relations with the European Union are strong, and two-thirds say the Europeans are more to blame for this poor relationship than Turkey. More than 60 percent of Turks believe the EU-Turkish migration deal was bad for Turkey, fed in part by deep resentment of the presence of 3.5 million Syrian refugees.9 A majority of Turks say their country has fulfilled its side of the bargain, while just 10 percent felt the European Union had done its part. Three-quarters of Turks say any withdrawal of EU funds or suspension of the accession process would be unjustified.

Expanding the customs agreement with Turkey—often put forward as an option to rejuvenate ties—would likely have little effect on Turks’ attitudes toward the European Union, meanwhile, despite a high level of knowledge on the issue. Turkish citizens remain broadly supportive of NATO, but many also support building a lasting alliance with Russia, an idea which earned 57 percent support—a new trend in Turkish political attitudes.10 Despite their support for both NATO and a potential Russian alliance, Turks are deeply mistrustful of both powers, but they trust the United States significantly less than they do Russia. Taken together, these findings portray a Turkish public who would like to be connected to Europe despite some animosity toward the European Union, as well as a feeling of betrayal or abandonment in the face of the refugee crisis and a disingenuous EU accession process. While Turks seem to see little prospect for improvement, they feel a harsher approach from the European Union would be unfair.

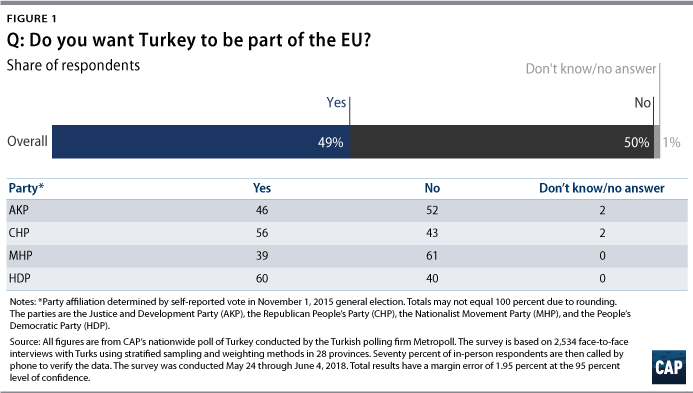

Do you want Turkey to be a part of the European Union?

Turkish EU membership is a disputed issue but does not break down along clear partisan lines—a rarity in modern Turkey, where nearly every issue is defined by party allegiance. Essentially, after years without progress and frequent public recriminations on both sides, Turks are deeply ambivalent about EU membership.

Overall, 49 percent of respondents said they wanted Turkey to be part of the European Union, while 50 percent said they did not. The Justice and Development Party (AKP)11 was slightly more negative on EU membership, with 46 percent in favor and 52 percent opposed. The opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) was more positive, with 56 percent in favor of membership and 43 percent opposed, but this was a matter of degree. The Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) was, not surprisingly, the most hostile toward EU membership, with 39 percent in favor and 61 percent opposed, while the People’s Democratic Party (HDP) was most supportive, with 60 percent in favor and 40 percent opposed. The overwhelming percentage of HDP voters are Kurds; thus, the HDP figures reflect a meaningful ethnic divide, with Kurds significantly more supportive of EU membership than Turks. In fact, it is surprising that as many as 40 percent of HDP voters opposed EU membership, as EU membership is often seen as a way to pressure Ankara to satisfy Kurdish cultural and linguistic demands.12 Perhaps also surprisingly, there were no other major demographic shifts on this question—younger and more educated Turks were only slightly more likely to support EU membership than their older or less educated counterparts. Overall, these results are surprising—the desirability of EU membership used to be an article of faith for members of the Turkish opposition, who generally felt it would help modernize Turkey’s economy and government and restrain the AKP.13 Clearly, years of waiting for progress on EU accession in the face of mixed messages from Europe and the abandonment of reforms in Turkey have taken their toll across the Turkish political spectrum.

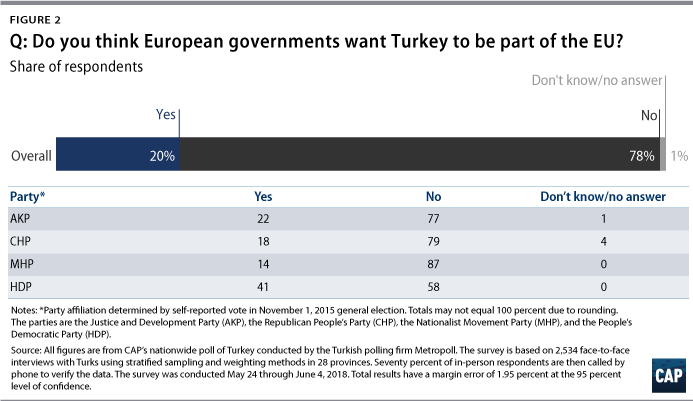

Do you think European governments want Turkey to be part of the European Union?

While Turks are divided about whether they want Turkey to be part of the European Union, they are certain that European governments do not want Turkey to join the bloc.

Overall, just 20 percent of Turks think European governments want Turkey to be part of the European Union, while 78 percent think the opposite. Again, this is not a partisan issue in Turkey—there is broad agreement that the Europeans do not want Turkey. This consensus is likely the result of a lack of functional progress on accession—no new chapter in the accession process has begun in more than two years—as well as widespread negative coverage of the European Union in the Turkish press and the rise of right-wing populists in parts of the European Union, giving platforms to European conservatives with harsh views of Turkey.14 Equally, there do not appear to be any meaningful demographic differences on this question; differences in income, gender, age, and education do not change the results. One minor note: HDP voters and Kurds hold more belief that European governments are open to Turkey’s EU accession.

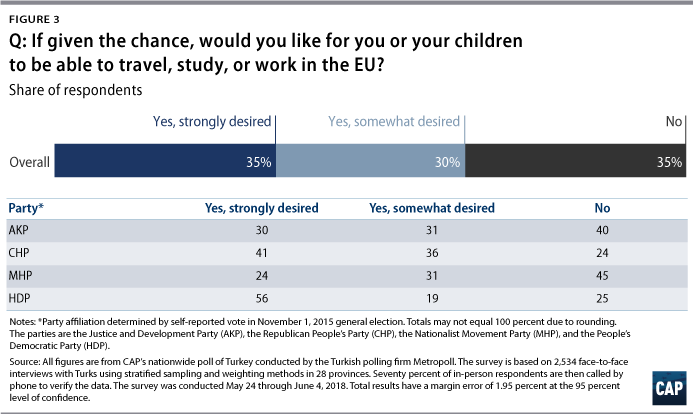

If given the chance, would you like for you or your children to be able to travel, study, and work freely in the European Union?

Most Turks see the appeal of traveling, studying, and working in the European Union. Overall, 65 percent of Turks would like to be able to engage freely with and within the bloc, and 35 percent strongly desire that access. Just 35 percent of Turks do not want access to the European Union.

As one might expect, the more nationalist and rural AKP and MHP are less interested in EU access for themselves and their children, but the partisan divides are not as stark as on many other political issues. Despite their stronger reluctance, majorities of respondents from both the AKP and MHP still favor access to some extent. For AKP voters, 30 percent strongly desire EU access, 31 percent somewhat desire it, and 40 percent do not desire it. For MHP voters, 24 percent strongly desire access, 31 percent somewhat desire it, and 45 percent do not desire it. As one might expect based on previous CAP polling,15 CHP and HDP voters are strong in their desire to travel, study, and work in the European Union. Among CHP voters, 41 percent strongly desire access, 36 percent somewhat desire it, and 24 percent do not desire it. Among HDP voters, the totals are 56 percent, 19 percent, and 25 percent, respectively. Finally, younger and more educated Turks are noticeably stronger in their desire to interact with the European Union compared with their older and less educated peers.

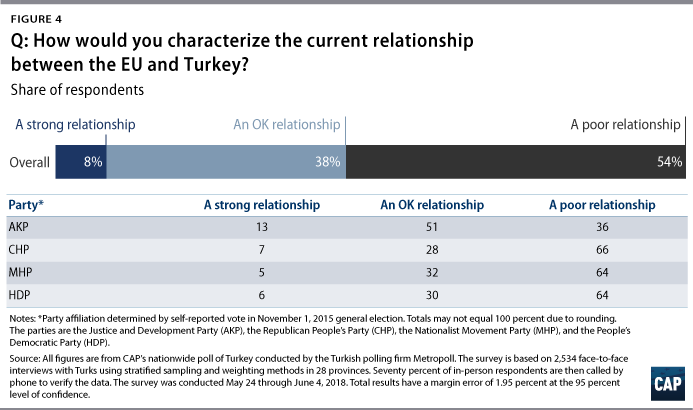

How would you characterize the current relationship between the European Union and Turkey?

Most Turks acknowledge that Turkey’s relationship with the European Union is poor, though AKP voters are more likely to see the positive side of relations.

Overall, 54 percent of Turks say relations are poor, 38 percent say relations are OK, and just 8 percent say relations are strong. There are noticeable party differences on this issue, as just 36 percent of AKP voters say EU-Turkish relations are poor, compared with 65 percent of opposition voters. Wealthier and more educated respondents were more likely to believe that relations are poor. Most likely, these respondents from urban areas have more exposure to the reality of strained ties with Europe—both through contact with European visitors and through exposure to independent media outlets and social media. In addition, AKP supporters may believe that, because an AKP government is managing the relationship with Europe, things are better than they appear. This last point is, perhaps, revealing of a value judgment that could be construed as positive: Good relations with Europe are worth prioritizing.

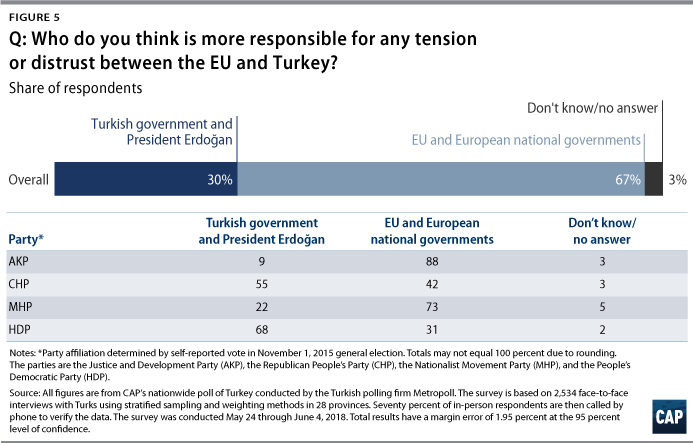

Who do you think is more responsible for any tensions or distrust between Turkey and the European Union?

Two-thirds of Turks believe the European Union and European national governments are more responsible than Turkey for the poor state of relations between Europe and Turkey, but this belief is fairly partisan. The AKP and MHP overwhelmingly blame Europe for the troubles in relations with the continent, by 88 percent and 73 percent, respectively. Conversely, majorities of the CHP and HDP believe Turkey is to blame, by 55 percent and 68 percent, respectively. Interestingly, the older a respondent was, the more likely they were to blame Turkey more for the difficulties—a surprising result considering the fact that AKP support tends to be higher among older voters.

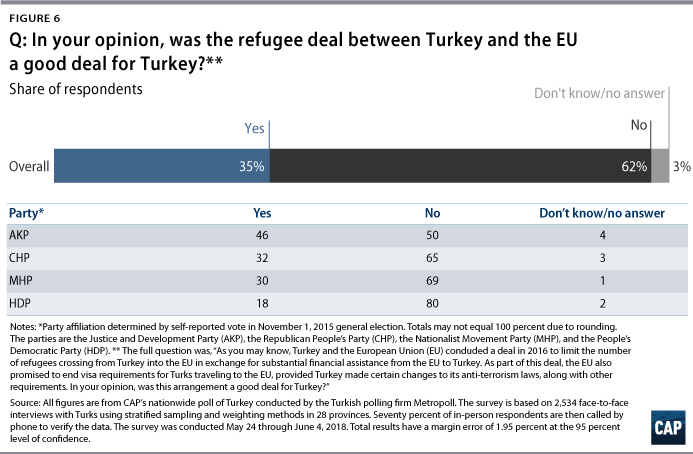

In your opinion, was the refugee deal between Turkey and the European Union a good deal for Turkey?

Nearly two-thirds of Turks—62 percent—believe the EU-Turkish migration deal was a bad deal for Turkey, while just 35 percent believe it was a good deal.16 Opposition voters were more likely to see the deal as bad for Turkey, but a majority of AKP supporters agreed, with 50 percent saying it was a bad deal and 46 percent saying it was a good deal. Interestingly, there were no meaningful demographic shifts when results were broken down by age, gender, income, ethnicity, or education.

This overall discontent with the terms of the EU migration deal may, in part, be explained by the overall anger among Turks about the size of the Syrian refugee population in the country. In CAP’s November 2017 poll, just 15 percent of Turks had favorable views of Syrian refugees, while 79 percent had unfavorable views.17 Opinions had softened somewhat by late May–early June 2018 but were still overwhelmingly negative: 67 percent of respondents had unfavorable views of Syrian refugees, with 43 percent reporting very unfavorable views.

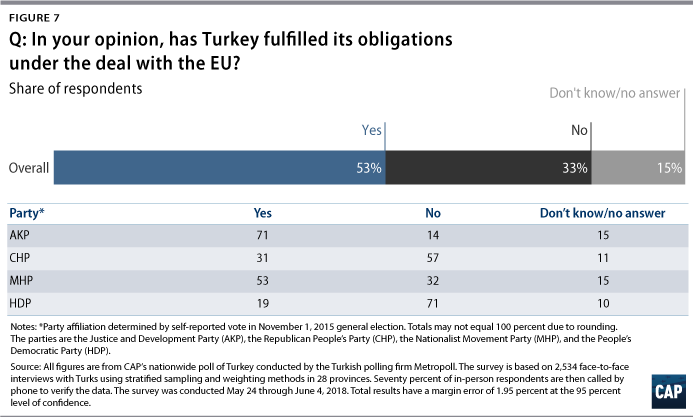

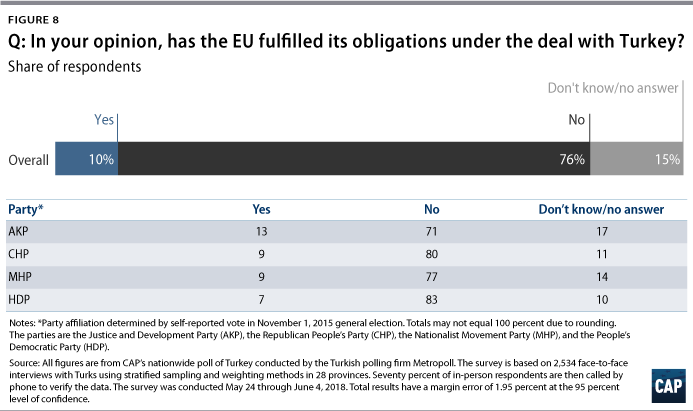

Has Turkey fulfilled its obligations under the refugee deal? Has the European Union fulfilled its obligations under the deal?

Turks may also view the refugee deal negatively, because they feel that while Turkey has fulfilled its obligations, Europe has not. Overall, 53 percent of Turks feel Turkey has fulfilled its obligations under the deal, while 33 percent feel the country has not done so. Turks are polarized along partisan lines on this question, with AKP supporters overwhelmingly saying Turkey has done its part, at 71 percent, while just 31 percent of CHP voters feel that way. Despite this partisan polarization, there were no meaningful demographic changes when results were broken down by age, gender, income, ethnicity, or education.

Meanwhile, three-quarters of respondents felt the European Union has not fulfilled its obligations under the deal, and just 10 percent felt the bloc had done so. There was broad agreement across party lines on this question and no meaningful demographic shifts when results were broken down by age, gender, income, ethnicity, or education.

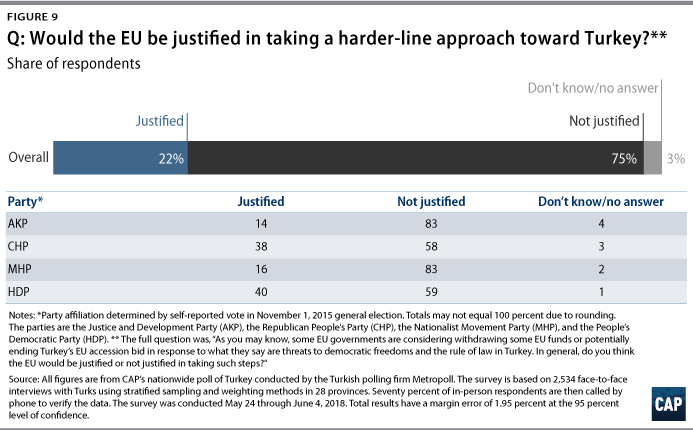

Would the European Union be justified in taking a harder-line approach toward Turkey, such as by suspending funding or the accession process?

An overwhelming majority of Turks reject the legitimacy of any potential harder-line, punitive EU approach toward Turkey.18 About three-quarters of respondents said withdrawing EU funds or ending the accession process would be unjustified, while just 22 percent felt it would be justified. While more than 80 percent of AKP and MHP voters felt that punitive steps would be unfair, there was broad consensus across political lines, and strong majorities of opposition voters—58 percent of CHP voters and 59 percent of HDP voters—agreed. More educated Turks were more likely to see potential punitive actions as justified, but strong majorities still felt they would be unjustified. There were no visible shifts when results were sorted for other demographic factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, or income. These figures likely reflect the general and long-standing Turkish public frustration with the European Union, including the belief that the bloc applies a double standard to Turkey that it does not apply to other countries aspiring to EU membership.

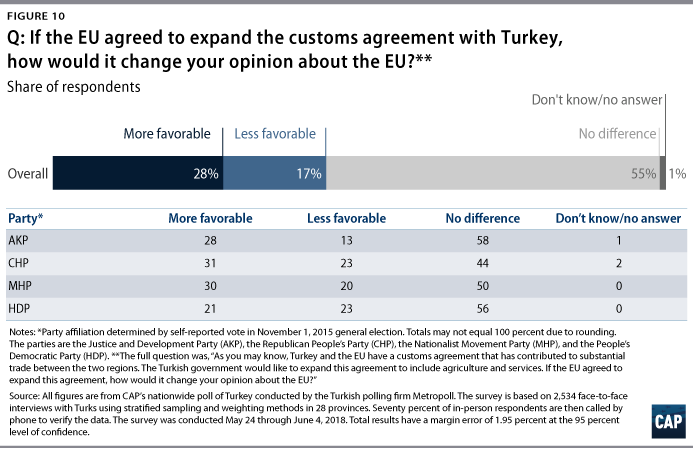

If the European Union agreed to expand the customs agreement it has with Turkey, how would it change your opinion about the European Union?

The proposed expansion of the EU-Turkish customs agreement would improve Turkish public attitudes toward the European Union but not by much.19 Overall, 28 percent of respondents said it would make them view the European Union more favorably, 17 percent said it would make them view the European Union less favorably, and 55 percent said it would make no difference in how they view the European Union. There is broad political consensus on this issue, with minimal shifts in responses among voters of different parties. There were no visible demographic shifts when results were broken down by age, gender, income, ethnicity, or education.

Turks were relatively familiar with developments regarding the EU-Turkish customs agreement: 67 percent said they were very or somewhat familiar with the issue, with just 32 percent saying they were not very familiar or not at all familiar with the issue. Since the issues are somewhat technical, this is surprising in itself.

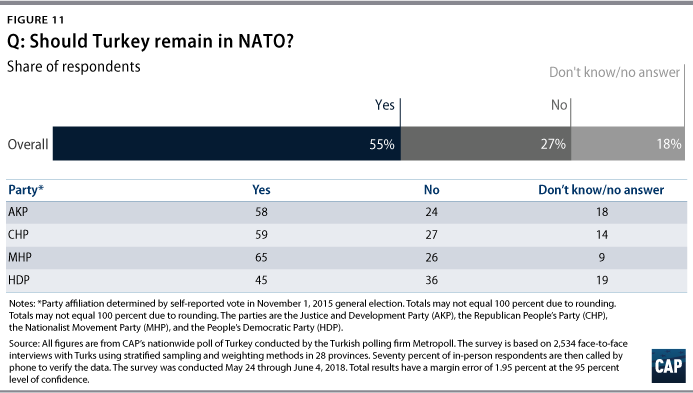

Should Turkey remain in NATO?

The Turkish public remains broadly supportive of NATO membership, with 55 percent saying the country should remain a part of the alliance, and just 27 percent saying it should not. Majorities of the AKP, CHP, and MHP believe Turkey should remain in NATO, while a plurality of HDP voters share that view. Surprisingly, given the party’s historical suspicion of the West, MHP voters were the most enthusiastic about remaining in NATO, with 65 percent saying it should do so. Younger, male, and more educated respondents were more supportive of continued NATO membership than older, female, and less educated respondents.

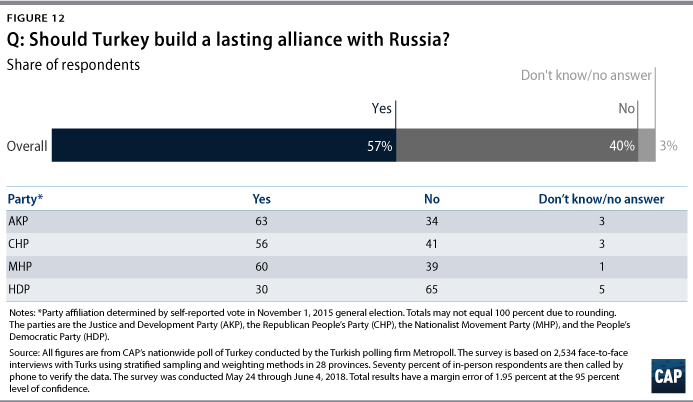

Should Turkey build a lasting alliance with Russia?

Turkish respondents also strongly support building a lasting alliance with Russia, with 57 percent supporting building such ties and 40 percent against doing so. Given the history of conflict between Russia and Turkey—and their respective predecessor states—this is a new and surprising shift. Indeed, Turkey’s NATO membership was driven by fear of Soviet aggression.20 Opinion was more polarized on Russian ties than it was on remaining in NATO: While more AKP voters want an alliance with Russia than support remaining in NATO, more AKP voters oppose any Russian alliance than want to leave NATO. Across political lines, there was strong support for building an alliance with Russia, except among HDP voters, 65 percent of whom do not support a Russian alliance. This may represent greater HDP and Kurdish affinity for the United States, given American support for the Kurdish cause in Syria, but this is speculation.21 Men were marginally more supportive of an alliance with Russia, but there were no meaningful visible demographic shifts when results were broken down by age, gender, income, ethnicity, or education.

This strong support for a lasting alliance with Russia may seem counterintuitive for Western readers, given Turkish public support for NATO membership, but is in keeping with President Erdoğan’s rhetoric that Turkey should cultivate independent ties with Russia, China, and Iran, despite its membership in the Western security architecture.

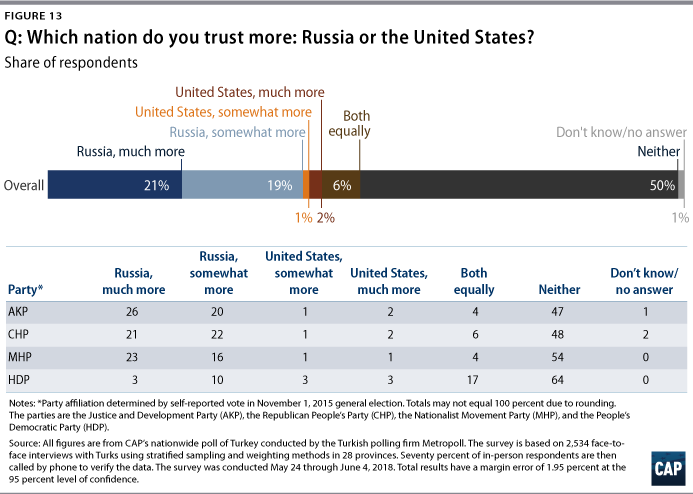

Which nation do you trust more: Russia or the United States?

In keeping with past polling results, the Turkish public shows little trust for either Russia or the United States, but mistrust is especially strong toward the United States. There is some evidence that the Russian-Turkish public rapprochement22 has had an impact on Turkish public opinion, and Russia has made inroads in terms of the trust and approval with which it is viewed by Turks.

Overall, half of respondents said they did not trust either Russia or the United States; 6 percent said they trust both equally; 40 percent said they trust Russia much more or somewhat more; and just 3 percent said they trust the United States much more or somewhat more. Given Turkey’s historical antipathy toward and conflicts with Russia—as well as its treaty alliance with the United States—these are remarkable results.23 There were minimal political shifts when results were broken down by party; the AKP, CHP, and MHP broadly share a deep mistrust of the United States and a growing trust in Russia. The MHP number is noteworthy: During the Cold War, many Turkish nationalists hated the Soviets not just for their communist ideology, but also because they saw them as the oppressors of the Turkic people of Central Asia. Clearly, this antipathy is fading vis-a-vis modern-day Russia. Although the HDP shares this overall political consensus at a basic level, HDP voters show much more skepticism toward Russia, with just 13 percent saying they trust Russia more and 6 percent saying they trust the United States more. There were no clear demographic shifts when results were broken down by age, gender, income, ethnicity, or education.

Conclusion

Years of controversies with the European Union—as well as with NATO and the United States—have left the Turkish public deeply skeptical of Western intentions and the prospects of Turkish EU membership. The Turkish public understands relations are very poor and largely holds the European Union and European governments responsible for that fact. Despite the current Turkish government charm offensive in Europe, there is limited room for governments on either side to substantially reset relations with public attitudes so negative on both sides of the relationship. Years of negative coverage in the Turkish press—and often unhelpful comments from European leaders looking to curry favor with conservative constituencies hostile toward Turkey24—have mired the relationship in mistrust and hostility, and there is little hope for improvement in the near term. Indeed, the most likely big positive step—a potential customs agreement expansion—barely moves the needle, and equally likely punitive EU measures would illicit very negative reactions from the Turkish public. Still, the Turkish public sees the attraction of the European Union and wants to travel, work, and study within the bloc. Turks likewise see the value in NATO, despite deep mistrust of the United States and rapprochement with Russia.

The depth of Turkish public skepticism about—and even hostility toward—the European Union and the intentions of European governments mean that Turkey’s charm offensive to rejuvenate ties with Europe faces a difficult path forward. Political leaders on both sides must maintain credibility and popularity with constituencies that have, over many years, been taught to view the opposite side—variously, Turkey and the European Union—with suspicion. Given this atmosphere of distrust; harsh Turkish government statements about Europe; right-wing European anger about immigration and Islam; and the strain placed on the relationship by the refugee crisis and Turkey’s economic downturn, it will take astute management to prevent another outright, public breakdown in relations over the next year. Still, Turkey’s economic future, by necessity, lies with the European Union, due to the size and proximity of its market and the depth of its financial resources. The Turkish government must patch up relations if Turkey is to prosper, but it has been mortgaging that future in pursuit of domestic political gain for too long. European governments, meanwhile, should be honest with Turkey—EU accession is entirely unrealistic for the foreseeable future, and work should instead begin to rejuvenate ties and build a relationship that protects the core interests of both sides.

Max Hoffman is the associate director of National Security and International Policy at American Progress, focusing on Turkey and the Kurdish regions.

The Center for American Progress would like to thank the Istanbul Policy Center-Sabanci University-Stiftung Mercator Initiative for its continued support of its research on Turkey, Europe, and their relationships with the world. The Center is also grateful to Metropoll Strategic and Social Research Center for its excellent conduct of the nationwide poll.