Introduction and summary

The U.S. economy has recovered steadily since the 2007-2008 financial crisis, but the slow rate of economic growth has been, and continues to be, concerning to workers, families, and policymakers.1 Finding ways to bolster economic growth in a sustainable and inclusive manner has been, at least rhetorically, at the top of the legislative and regulatory agenda. Policymakers have targeted financial regulation as a potential mechanism for spurring economic growth. Financial regulation—as opposed to public investments or other aspects of fiscal policy—may seem like an unusual place to look for ways to improve the health and overall growth prospects of the U.S. economy. But in fact, financial regulation is essential for economic growth.

Banks are crucial intermediaries between savers and borrowers. Bank loans and other products and services help entrepreneurs, small businesses, and large corporations fund economically useful projects and manage risk. In this vital economic role, a safe and sound financial sector is of paramount importance to economic growth, and research shows that enhanced financial stability safeguards lead to improved economic growth. Banks with higher loss-absorbing equity capital—which can significantly limit the chances of financial crises—see more lending over the long term compared with undercapitalized banks, which rely too heavily on debt.2 Data from the 2007-2008 crisis clearly demonstrate that financial crises have devastating impacts on lending. At the height of the financial crisis, between October 2008 and October 2010, overall lending declined by 6 percent.3 During that same period, bank lending to businesses declined even more dramatically, dropping 25 percent.4 Furthermore, the Bank for International Settlements recently released a report concluding that countries that actively regulate the financial sector overall—by employing what are known as macroprudential policies in order to address systemic risk in the financial system—experience higher, less volatile gross domestic product growth per capita.5 U.S. banks face more stringent regulations than European banks and have fared better from a lending and profitability standpoint due to the more robust regulatory regime in place.6 In November 2016, Gary Cohn, director of the National Economic Council and former president of Goldman Sachs, argued that the health of U.S. banks in relation to their global counterparts is a competitive advantage for the U.S. economy.7

Financial instability has always been one of the gravest threats to healthy economic growth. Although the shock and fear caused by the 2007-2008 financial crisis appear to be fading from collective memory, the massive disruption of financial stability has had severe and lasting impacts on U.S. economic growth. Unemployment skyrocketed to 10 percent, 10 million homes were lost, and $19 trillion in wealth was wiped out.8 Between 2007 and 2010, the real wealth of the average middle-class family plummeted by nearly $100,000, or 52 percent.9 Furthermore, too many workers and families endure lasting economic difficulties to this day. In the current low interest rate environment, there remains the concern that banks may take on excessive risk to boost profits, which could lead to asset price bubbles and other market distortions. These are risks that demand policymakers remain committed to sound regulatory approaches.

Financial regulation also plays an important role in cushioning other parts of the economy from the inevitable ups and downs of financial markets. In particular, it provides a measure of protection against the volatility and negative economic impact on households that follow the buildup of risk in the financial sector. Similarly, solid regulation protects the public treasury—the taxpayers and those concerned about the public debt—from the very real risks that accompany often shocking levels of governmental support provided to bolster the financial system after a crisis. Policymakers then use the public debt as a cudgel to enact austerity measures that further harm the middle- and working-class families who participate in important public programs—another instance that emphasizes financial regulation’s critical role in protecting all aspects of the interaction between government and society.10 Additionally, financial stability helps reinforce the effectiveness of monetary policy efforts to kick-start broad-based economic growth.

Accordingly, it would make sense that the conversation around improving long-term economic growth would include probing whether there are ways to further enhance and strengthen financial stability safeguards. Conservative policymakers in Congress and in the Trump administration, however, have asked the opposite question, as the policy debate thus far has dangerously zeroed in on Wall Street deregulation to spur growth.

The first section of this report outlines the vicious cycle of deregulation that has been repeated throughout modern history and includes a brief overview of key banking deregulatory proposals set forth by Congress and the Trump administration. The next sections detail bank capital requirements, the Volcker rule, and liquidity requirements, offering policy recommendations that build on the progress made in each respective area since the crisis, as well as provide guidance on how to better implement financial reform. These recommendations include increasing the loss-absorbing capital cushions for the largest banks; tightening the Volcker rule by eliminating loopholes for merchant banking, commodities investments, and currency trading, as well as improving transparency surrounding the rule’s implementation and enforcement; strengthening banks’ liquidity resilience through capital calculations; and improving the financial system’s liquidity and resilience by requiring all repurchase (repo) agreements and securities-lending contracts to be centrally cleared, including requirements for risk-based default fund payments from clearing members to help prevent central counterparty (CCP) defaults.

Much like the U.S. Treasury Department’s financial regulation reports, which break up its proposals by issue area, in separate publications, the Center for American Progress will release other affirmative proposals addressing ways to improve the implementation of financial reform for financial markets, consumer protections, housing policy, and other financial regulatory issues.

The vicious cycle of deregulation

Ten years after the beginning of the 2007-2008 financial crisis and seven years since the passage of financial reform in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, it is not only natural but also necessary for regulators, policymakers, and the public to assess the efficacy of financial reform efforts and implementation. The policy analysis and debate surrounding how to fine-tune financial regulation is a healthy impulse, and tying this review to economic growth prospects makes sense if it is based upon sound theories and evidence. Stagnant regulatory regimes ignore new data, research, and other empirical evidence that can help improve the resilience of evolving financial markets and institutions and, in turn, limit the chances and severity of future crises.

However, the historical record is not favorable to those who undertake this type of financial regulatory self-reflection and modernization in the name of boosting economic growth. Past legislators and regulators have had a tendency to loosen financial regulations over time at the behest of the financial sector—and as the memories of previous financial crises fade. Amid usually specious financial sector claims that postcrisis financial regulations restrict bank credit and thus hamper economic growth, history demonstrates that the other side of the ledger—the severe economic cost of financial crises and their impact on long-term economic growth—loses its voice in the debate. Alan Blinder, former vice chairman of the Federal Reserve board of governors, provides the basic outline of this cycle—and the key factors that drive this outcome—in his financial entropy theorem.11 Blinder points to the erosion over time of the Glass-Steagall Act’s separation between commercial and investment banking; the loosening of interstate banking regulations in the 1980s and 1990s; and the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000’s prohibition on derivatives regulation as historical examples of all or part of the deregulatory cycle.12 University of Colorado Law School professor Erik Gerding outlines a similar concept to explain why financial regulations tend to erode during financial bubbles—the time they are most needed—in his regulatory instability hypothesis.13 Put more simply, former Comptroller of the Currency Thomas Curry observed that “the worst loans are made in the best of times.”14

Unfortunately, the current policy debate surrounding changes to the Dodd-Frank Act and the postcrisis regulatory regime to date is following the historical trend.

In June, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Financial Choice Act 233-186. It was endorsed by the Trump administration, and President Donald Trump praised it on Twitter.15 The Financial Choice Act would thoroughly dismantle the postcrisis financial reforms enacted by the Dodd-Frank Act. It would allow banks to opt out of risk-based capital requirements, liquidity requirements, stress testing, living wills, and more—as long as banks meet a modestly higher leverage ratio. The bill would also gut the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC)—the new systemic risk regulatory body established by Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act—eliminating its ability to subject systemically important nonbanks such as American International Group (AIG) to stricter regulation. Additionally, the Financial Choice Act repeals the Volcker rule, as well as the new tool that regulators were granted to wind down large, complex financial institutions. In short, the bill is a full-frontal attack on financial reform—and worse, it also targets federal banking laws that have been in place for decades. It has yet to advance in the U.S. Senate.

Just a week after the passage of the Financial Choice Act, the Department of the Treasury entered the policy conversation by releasing the first in a series of financial regulatory reports mandated by an executive order issued by President Trump in February.16 Some of the report’s policy recommendations, especially with regard to smaller financial institutions, are reasonable and worthy of further debate. Unfortunately, many of the recommendations—framed as regulatory tweaks—would significantly undermine crucial postcrisis reforms on liquidity rules, capital requirements, stress testing, and more.

In March, the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs issued a call for proposals to boost economic growth, and it has held several hearings on the topic in recent months.17 On November 13, 2017, Sen. Mike Crapo (R-ID), the chairman of the Senate banking committee, announced a bipartisan agreement with 10 members of the Democratic caucus on a piece of legislation that would deregulate 25 of the nation’s 38 largest banks, water down important housing protections, and create a large Volcker rule loophole in the course of exempting community banks.18 The bill includes a few limited provisions that enhance consumer protection. The Dodd-Frank Act requires regulators to apply stricter regulation and oversight to the 40 largest banks in the United States—those that have assets of more than $50 billion. The centerpiece of the bipartisan Senate bill is a provision that would increase this threshold to $250 billion, meaning 25 banks with a combined $3.5 trillion in assets would be deregulated. These banks are large, and the failure of several of them during a period of severe stress in the financial system would negatively affect the regional economies that they serve and could disrupt U.S. financial stability. Moreover, these 25 banks combined took almost $50 billion in direct bailout funds during the crisis.19 It is eminently sensible to require an increase in oversight as banks get bigger and more complex, as a $100 billion bank presents different risks compared with a community bank. The Dodd-Frank Act already gives regulators the authority, which they have exercised, to subject truly global banks to even stricter oversight and regulations. Allowing large regional banks to no longer submit living wills to plan for their orderly failure; no longer face new liquidity requirements; and no longer engage in rigorous company-run stress testing and annual stress testing by the Federal Reserve required by Dodd-Frank is a serious mistake.

The bill also purports to offer relief to community banks with up to $10 billion in assets from the provisions of the Volcker rule. That part of the Dodd-Frank Act bars banks and their affiliates from engaging in proprietary trading activities—such as in stocks, bonds, and derivatives—or sponsoring or investing in a hedge fund or private equity fund, broadly defined. Unfortunately, the bill actually exempts financial firms far larger than community banks, potentially allowing financial firms of any size that engage in massive amounts of trading activities and fund sponsorship or investing to be exempt from the Volcker rule, even while retaining affiliation with the banking system.20 This report also discusses other provisions included in the bipartisan Senate banking bill, as well as other provisions in the Financial Choice Act and Treasury Department report.

Efforts to loosen financial reform have repeated the spurious claim that the Dodd-Frank Act has restricted lending and economic growth while also damaging market liquidity. President Trump summed up these claims when he stated at a White House meeting with Wall Street CEOs, “We expect to be cutting a lot out of Dodd-Frank because, frankly, I have so many people, friends of mine that had nice businesses, they can’t borrow money.”21 U.S. House Committee on Financial Services Chairman Jeb Hensarling (R-TX)—architect of the Financial Choice Act—has framed Dodd-Frank in similar terms.22 Critics of financial industry reform have echoed these concerns, emphasizing their view that the Dodd-Frank Act has impaired market liquidity.23 But there is no evidence to support these claims. Lending has rebounded significantly since the financial crisis and is at an all-time high, while market liquidity is well within historical norms.24 Furthermore, the economy has added more than 16 million jobs since 2010, and bank profits are at or near all-time highs.25 As previously stated, the strong thrust of recent evidence makes it clear that the economy needs financial stability to grow sustainably across the economic cycle.

After the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, reforming the financial sector’s regulatory landscape was a top legislative and regulatory priority for the Obama administration and Democratic-led Congress. The economic scarring was too devastating for policymakers or regulators to stick to the status quo. The key pillar of financial reform efforts, the Dodd-Frank Act, made significant progress in enhancing the resilience of the financial system and rooting out consumer and investor abuses that had run rampant in the lead-up to the crisis.

The loss-absorbing capacity of the banking sector—in particular, the loss-absorbing capacity of the largest, most systemically important banks—was increased with higher and more stringent risk-based capital requirements, as well as stronger leverage limits. New liquidity rules ensure that banks are better positioned to come up with the cash necessary to meet their obligations during times of stress and to utilize more stable funding, making them less susceptible to runs. The largest banks now undergo annual stress testing; the previously unregulated swaps market is subject to enhanced oversight and regulation; and a new systemic risk regulatory body—the FSOC—has the authority to subject systemically important nonbank firms to enhanced regulation and Federal Reserve oversight. Large banks are required to plan for their potential failure through the living-wills process, and regulators have been given the tools necessary to wind down large, complex firms in an orderly way—avoiding bailouts and catastrophic bankruptcies. As for the Dodd-Frank Act’s Volcker rule, which prohibited banks and their affiliates from engaging in proprietary trading and severely restricted their ability to own or invest in hedge funds and private equity funds, the available evidence suggests that the rule is working well to cut off swing-for-the-fences trading and tamp down high-risk activities.

The Dodd-Frank Act was a much-needed response to unchecked financial sector risk and consumer and investor abuses, but advocates for a well-regulated financial sector should continue to push for improvements to Dodd-Frank’s implementation as well as further policy changes to strengthen financial reform. Other large-scale proposals to drastically alter the financial sector and financial regulatory structure have merit, but the main focus of this report is adjustments to the current regulatory regime established by the Dodd-Frank Act.

Bank capital requirements

Capital requirements are the most fundamental tool that banking regulation has to lower the likelihood of bank failures, financial crises, and taxpayer-funded bailouts. This section provides an overview of what capital is and why it is a pillar of banking regulation. It then details the severe undercapitalization of the banking system prior to the financial crisis and highlights the progress made to increase capital following the crisis. It also outlines the current proposals set forth by Congress and the Trump administration to undermine postcrisis capital requirements. Finally, this section presents a review of research showing that while current bank capital levels are significantly improved, they are not yet high enough, and it outlines an affirmative proposal to increase capital requirements accordingly.

What is bank capital?

In most news articles or research reports, banks are referred to as “holding” a certain amount of capital. This gives the false impression that capital is essentially cash that banks set aside in a vault that is used to absorb losses but that cannot be used for loans or other productive purposes. It is worth briefly addressing this confusion by explaining what capital actually is and why it is important.26

Essentially, bank capital is the difference between the value of a bank’s assets—what the bank owns—and the value of its liabilities—what the bank must pay back to its creditors or depositors. For example, if a bank has $100 in assets, such as loans, and $90 in liabilities, such as deposits and other debt, then it has $10 in equity capital. That $10 is crucial for the bank, as it serves as a loss-absorbing buffer because capital is a category of funding that does not require repayment when the value of a bank’s assets declines. While debt payments are due on a fixed schedule, equity holders are not entitled to regular repayment—they merely receive distributions if a company has excess profits. If the value of the bank’s $100 in assets drops to $95, then it still has $5 of capital. But if the assets were to drop by more than $10 in value, the capital would be wiped out and the bank would not have enough value to pay off its liabilities—a scenario referred to as insolvency. Absent support from the government to prop up the bank, insolvency would result in the bank’s failure.

A key element of this description is that this equity—which is provided by shareholders when a bank issues stock or by retained earnings when a bank keeps its excess profits—is in no way set aside in a bank vault. The $100 in loans from the example is funded by the $90 in liabilities and the $10 in equity. Understanding this loss-absorbing function of capital and dispelling the notion that it is not used to fund loans and other assets is crucial to understanding the current bank capital debate. Other more nuanced misconceptions about bank capital and its impact on lending and economic growth will be addressed throughout this section.

Undercapitalization during the financial crisis

One of the banking system’s many problems in the lead-up to the 2007-2008 financial crisis was that it was severely undercapitalized. Regulatory capital requirements were too low, which allowed banks to rely heavily on debt, leaving them unable to absorb their substantial losses during the crisis. Examples of two distressed banks, Wachovia and Washington Mutual, are instructive.

At the start of the financial crisis in June 2007, the $300 billion commercial bank Washington Mutual had a tangible common equity capital-to-tangible assets ratio of 4.8 percent.27 Tangible common equity refers to the highest quality of capital that is available to fully absorb losses. There are other categories of capital, referred to as other tier one capital or tier two capital, both of which for nuanced reasons have some debtlike features that make them less adequate for absorbing losses.28 After booking roughly $6 billion in losses, Washington Mutual’s tangible common equity ratio dropped to 3.6 percent, meaning the bank was leveraged at almost 30-to-1.29 With this extremely low capital level and more trouble on the horizon, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) took over the bank and sold it to JPMorgan Chase. After acquisition, JPMorgan Chase wrote down $29 billion more in losses on Washington Mutual’s portfolio.30 When comparing the total losses of $35 billion with the bank’s assets at the start of the crisis, it equates to an 11.5 percent loss—meaning that the bank’s 4.8 percent common equity at the time was much too low to withstand the coming crisis.31

The failure of Wachovia, a much larger commercial bank with $700 billion in assets, reveals a similar picture of inadequate equity capital prior to the crisis. In the second quarter of 2007, Wachovia’s common equity capital ratio was 4.3 percent.32 By the end of 2008—when Wells Fargo acquired the failing bank and booked losses stemming from the acquisition—the losses totaled almost 9 percent of Wachovia’s second-quarter 2007 assets.33 As demonstrated by these two developments, and by research conducted on capital erosion by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, these losses occurred rapidly.34 When such losses piled up and left banks insolvent or close to it, lending in the banking sector plummeted—severely contracting economic growth.

The losses across the banking sector overwhelmed capital ratios, necessitating hundreds of billions of dollars in government bailout funds to replenish capital, as well as trillions of dollars of additional support in guarantees and liquidity facilities.35 More than 500 banks failed during this period.36 In 2009, 19 banks with more than $100 billion in assets—accounting for two-thirds of the assets and more than one-half of the loans in the U.S. banking system—were selected to take part in the first stress tests.37 Ten of the 19 participating firms were a combined $74.6 billion short of the stress test’s required capital ratios.38 The low level of regulatory capital requirements was not the only cause of the undercapitalization. Banks were also able to count the type of capital securities with debtlike qualities mentioned earlier as a higher portion of their capital requirements than was appropriate. This type of instrument—preferred stock, for example—could not absorb losses as well as common equity due to its contractual features. Counting hybrid securities toward primary capital ratios made banks look more well-capitalized than they actually were, because only common equity could be completely trusted to absorb losses. Moreover, banks and other financial institutions used derivatives and other off-balance-sheet vehicles to take on risk while avoiding the capital requirements that would accompany the same types of activities if they occurred on the balance sheet. Low capital requirements, the loose definition of what counted as capital, as well as the use of off-balance-sheet instruments, left the banking sector extremely leveraged and vulnerable to a negative financial shock.

Bank capital positions have improved

Since the financial crisis, much progress has been made to address the banking sector’s capital shortcomings. Internationally, regulators worked together at the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS)—a consensus-driven standard-setting body that brings together regulators from around the world to negotiate banking policies—and agreed upon the Basel III framework. At the time, U.S. regulators played a leading role in driving the Basel process. In the framework, capital requirements—including the definition of what qualifies as capital and the treatment of off-balance-sheet exposures—were significantly strengthened.

In the Dodd-Frank Act, U.S. regulators were directed to set minimum capital requirements and leverage requirements for consolidated bank holding companies that were no lower than those that applied to banks and were authorized to subject banks with more than $50 billion in assets to enhanced capital and leverage requirements tailored to their size and risk profiles.39 Through public rule-makings, U.S. regulators implemented a modified Basel III capital framework and Dodd-Frank capital-related provisions, including enhanced leverage ratios and capital surcharges for the largest, most systemic U.S. banks. Since the first quarter of 2009, the 34 largest bank holding companies—which constitute more than 75 percent of the banking sector’s assets—have raised their common equity capital-to-risk-weighted assets ratio from 5.5 percent to 12.5 percent by the first quarter of 2017.40 To put those figures in context, these 34 banks have increased their highest quality capital buffers by $750 billion.41 According to the FDIC, the banking industry’s aggregate risk-based equity capital ratio has exceeded 11 percent every quarter since mid-2010—a level that the industry had previously never surpassed.42 Furthermore, there were fewer than 10 bank failures in both 2015 and 2016, compared with the more than 500 banks that failed during the crisis.43 Thanks to Basel III and the Dodd-Frank Act, the banking sector has come a long way in improving its capital positions.

Recent efforts to loosen capital requirements

In June, the Treasury Department released a report on banking regulations in response to President Trump’s February executive order on financial regulation.44 While the report included some reasonable policy recommendations regarding simplifying capital requirements for small community banks, it also included recommendations to loosen bank capital requirements, which would increase risks to financial stability. The report recommends an esoteric change to the calculation of the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR), one of the new capital requirements included in Basel III that applies to the largest banks.

Banks are required to adhere to two types of capital requirements—risk-weighted capital and leverage limits. Risk-weighted capital requirements assign weights to different types of assets based on their riskiness. Safe Treasury securities receive a zero percent risk weight, for example, while a corporate bond will receive a much higher percentage weighting. Leverage requirements such as the SLR, on the other hand, are risk-blind. Assets do not receive a risk weight and are all treated the same, making this a more holistic standard. It is a simpler way to calculate leverage and does not rely on regulators to calibrate risk weights appropriately. As a result, leverage ratios are lower than capital ratios.

Both risk-based capital requirements and leverage requirements have their pros and cons; making use of both is therefore crucial. Leverage requirements do not penalize banks for increasing the riskiness of their assets. Risk-based capital requirements are more complex and have been gamed in the past through financial engineering, and regulators are not perfect at predicting the riskiness of entire assets classes, so the risk weights can be improperly calibrated, leaving banks vulnerable. Therefore, risk-weighted capital and leverage ratio work in tandem.

The Treasury report recommends removing certain assets—cash, Treasury securities, and margin held against centrally cleared derivatives—from the denominator of the leverage ratio calculation. This is the functional equivalent of assigning a zero percent risk weight to these assets, undermining the entire purpose of the leverage ratio. This change would lower the leverage capital requirement for the largest banks by tens of billions of dollars each. Unfortunately, market regulators such as the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission have also advocated for some of these weakening proposals.45 And oddly enough, even the Treasury report’s appendix disagrees with this recommendation. When describing the importance of the leverage ratio, the appendix states, “Leverage capital requirements are not intended to adjust for real or perceived differences in the risk profile of different types of exposures. … As such, the leverage ratio requirements complement the risk-based capital requirements that are based on the composition of a firm’s exposures.”46

A narrower version of the Treasury proposal is included in the bipartisan Senate banking bill. That provision would require regulators to exclude cash held at central banks from the denominator of the SLR only for custody banks. Custody banks are vital for the U.S. economy. Combined, the largest custody banks, which are subject to the SLR, are the custodians of roughly $65 trillion in assets for their clients, which include pension funds, endowments, insurance companies, and other institutions.47 These banks also provide clearing, settlement, and execution services to their clients—essential plumbing services for the financial sector. The proposed change to the SLR for custody banks aims to address a potential problem that may arise during a financial crisis. When their institutional clients liquidate securities—which are held in custody by the custody banks off balance sheet—en masse during a crisis to flee to cash, it is possible that cash will be deposited quickly at the custody bank on balance sheet. The custody bank would likely put this influx of cash into central bank deposits. The bank’s risk-weighted capital level would be unchanged, as central bank deposits receive a zero percent risk weight, but the leverage ratio would decline. Changing the calculation of the SLR for these banks, which would lower their capital requirements today, to address this quirk that would likely last one or two weeks at the height of a financial crisis, is far too broad an approach to the problem. Providing regulators with additional emergency authority to exclude a rapid influx of deposits parked at central banks during a crisis from the calculation or further clarifying regulators’ existing authority to deal with this issue may be appropriate. Moreover, regulators should explore other avenues for where these large institutional investors could park their cash during a crisis. Undermining the principle of the leverage ratio through a change in the calculation is unwise and would open the door to further erosion of the SLR, representing the “thin end of a thick wedge,” as elegantly put by the Systemic Risk Council.48

In addition to the statutory risk-weighted capital and leverage requirements for banks, the annual stress tests conducted by the Federal Reserve serve as an additional dynamic capital requirement for banks. The Dodd-Frank Act Stress Tests (DFAST) and the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) conducted by the Federal Reserve test the balance sheets of banks with more than $50 billion in assets to ensure that they can withstand adverse and severely adverse scenarios while maintaining the minimum applicable capital cushions.49 The CCAR also includes a qualitative component for banks with more than $250 billion in assets, in which the Federal Reserve analyzes a bank’s internal risk-management and capital-planning processes. Through the CCAR, the Federal Reserve can restrict the amount of capital a bank can distribute through share buybacks and dividends. The Treasury Department report recommended that the Federal Reserve open the CCAR process, models, scenarios, and other aspects of the exercise to public notice and comment in the name of transparency.50 Federal Reserve Vice Chair for Bank Supervision Randal Quarles and Federal Reserve Board Chair nominee Jay Powell have signaled interest in pursuing this recommendation.51 This change would undermine the effectiveness of the annual stress tests and in turn could limit the eventual capital cushions that the Federal Reserve requires banks to maintain. If a bank knows what the adverse and severely adverse scenarios are prior to the stress test, it may modify its balance sheet accordingly to limit its projected losses and consequently, required capital.52 Once the stress testing is over, the bank would likely then shift its balance sheet back to its prestress-testing composition. During the stress tests, this would likely increase the correlation risk between institutions—as their balance sheets would be tailored to the given scenario and economic models used by the Federal Reserve.

Financial shocks are by their very nature surprises. Banks should not be given the test beforehand, as Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) correctly argued during Vice Chair Quarles’ confirmation hearing.53 Moreover, allowing the banks to comment on the scenarios and economic models gives them an opportunity to influence the substance of the exercise. Banks will likely lobby for lax macroeconomic scenarios and more favorable economic model assumptions that line up with their business incentives. Genuine transparency on stress testing that does not undercut the entire purpose of the testing is a worthy goal—and the Federal Reserve has significantly improved transparency over the past seven years. The Fed’s public release of the 2011 CCAR results was 21 pages and did not include a bank-by-bank breakdown of pre- and post-scenario capital levels.54 By contrast, the 2016 CCAR public release was 100 pages and included detailed bank-by-bank information with an explanation of the adverse and severely adverse economic scenarios.55 Changes to the stress-testing regime must not undermine the utility of the annual exercise.

Finally, the Treasury report also recommended that U.S. regulators delay implementation of the fundamental review of the trading book (FRTB), which refers to a revised minimum capital standard for the market risk posed by a bank’s trading activities.56 The BCBS released its final update on the FRTB in January 2016.57 U.S. regulators have not yet implemented the rule. The revised requirement would have the net effect of increasing the capital requirements for bank trading activities to more accurately account for the riskiness of those activities.58 Further delaying implementation of these enhanced standards for some of the riskiest activities at the largest banks would be a mistake.

Justifications to lower capital fall short

The conservative and industry-driven justification given for rolling back capital requirements is that strong capital requirements hamper banks’ ability to lend and in turn, dampen economic growth. Opponents of increased capital argue that stronger requirements drive up the funding costs of banks, because equity, commensurate with the increased risk of being in a first-loss position, demands a higher rate of return than debt. The cost is then passed to consumers. Opponents assert that more expensive lending means less lending, which in turn means slower economic growth.

For example, this past February, President Trump claimed that his friends could not get loans because of Dodd-Frank. The Clearing House, a trade association for the largest global commercial banks, also claims that increased capital requirements, namely the leverage ratio, increase the cost of banking services—and in turn significantly limit lending and economic growth.59 In 2015, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce warned that increased risk-weighted capital requirements on the largest banks—known as the globally systemically important bank (G-SIB) capital surcharge—would “create a drag on our financial services sector, and raise the costs of capital for all businesses.”60 In similar terms, the American Bankers Association claimed that the G-SIB surcharge “would be detrimental to U.S. bank customers and the institutions that serve them.”61 The Treasury Department report repeatedly talks about the costs of bank capital—the burdens bank capital places on certain loan asset classes—and it argues that lending has been historically slow to recover, in part due to excessive regulations.62

The evidence simply does not back up these claims. Lending has rebounded significantly since the financial crisis and is currently higher than ever.63 The economy has added more than 16 million jobs since the Dodd-Frank Act was signed into law on July 21, 2010, while the unemployment rate dropped from 9.4 percent in July 2010 to 4.1 percent in October 2017.64 This lending growth and economic recovery all occurred as the banking sector doubled its capital levels—not to mention the fact that bank profits are at record levels and that banks are choosing to return even more capital to their shareholders instead of using it to fund more loans.65 In the FDIC’s Quarterly Banking Profile for the third quarter of 2017, banks reported a combined net income of $47.9 billion, and the industry’s average return on assets remained strong after hitting a 10-year high in the second quarter.66 Lending continues to climb, with total loans and leases up 3.5 percent in the past 12 months.67 Community banks, which have been subject to a trend of consolidation since the 1970s, have had sustained loan and profitability growth since the financial crisis.68 A safe and sound financial sector is a source of strength for economic growth.

Significant research bolsters the previously outlined prima-facie case that bank capital requirements have not harmed economic growth. Research from Leonardo Gambacorta and Hyun Song Shin at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) shows that an increase in a bank’s equity capital lowers the cost of that bank’s debt and is associated with an increase in annual loan growth.69 This empirical study supports a theoretical claim about bank funding costs, known as the Modigliani-Miller theorem. It is true that equity investors demand a higher rate of return than debt investors—reflecting equity’s higher risk, as it is in a first-loss position. But the Modigliani-Miller theorem holds that when a bank shifts its funding more toward equity, the increase in funding cost is offset by equity investors and debt investors both demanding a lower return because the bank has more equity and is therefore safer.70 The mix of debt and equity do not affect a bank’s total funding costs. This theorem is somewhat skewed in practice by the tax treatment of debt versus equity, making debt cheaper than it otherwise would be. As demonstrated in the BIS study, however, the offset does exist to some extent. Research on the exact impact of increased capital on funding costs and lending differs, but the clear majority of studies show a negligible or modest impact.71 Further research from the BIS showed that banks with higher capital coming out of the financial crisis expanded lending more quickly.72

Furthermore, former Director of the Office of Financial Stability Policy and Research at the Federal Reserve Board Nellie Liang concludes that there is no evidence that higher capital requirements have constrained lending.73 Thomas Hoenig, the vice chair for the FDIC, agrees with this research, stating in a 2015 Wall Street Journal op-ed, “Banks with stronger capital positions maintain higher levels of lending over the course of economic cycles than those with less capital.”74 Hoenig also concluded in a 2016 speech at a Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) conference, “Strong capital levels support growth over the business cycle and are good for the economy.”75

And to be fair, not all conservatives are opposed to higher capital. Scholars at the conservative think tanks American Enterprise Institute and the Mercatus Center have argued that current capital requirements are too low.76 Moreover, in the comprehensive summary for the Financial Choice Act, Chairman Hensarling combats the claim that increased capital requirements hurt lending and economic growth.77 The summary cites several of the sources referenced above. Unfortunately, the Financial Choice Act calls for only modestly higher capital, while allowing banks that choose the higher capital off-ramp to opt out of a suite of other crucial financial regulatory requirements, such as liquidity rules, stress tests, and counterparty credit limits. While some well-respected academics agree that higher capital can replace some or all of the additional prudential regulations included in the Dodd-Frank Act, the Financial Choice Act’s capital increase is significantly lower than what those academics suggest. For example, Stanford Graduate School of Business professor and financial regulatory expert Anat Admati recommends a leverage ratio of 20 percent to 30 percent, which is substantially higher than the Financial Choice Act’s 10 percent requirement.78 Even with higher capital requirements, liquidity requirements, stress testing, living wills, and other prudential measures serve as complements to ensure the safety and soundness of the banking sector.

While improved, current capital levels are still too low

Recent research from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Federal Reserve, the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, and some academics has challenged the idea that current capital requirements are calibrated to socially optimal levels, suggesting that an increase in capital requirements at the largest banks is appropriate. The concept of the socially optimal level of capital refers to the calibration of capital requirements that maximize the economic benefits of lowering the chances of financial crises, while limiting an increase in bank funding costs that could increase the cost of lending.

The 2016 IMF study concludes that capital in the range of 15 percent through 23 percent of risk-weighted assets would have been sufficient for banks in advanced economies to absorb losses and avoid most previous financial crises.79 The study takes a global view and looks at losses across countries, particularly ones classified as advanced economies. The Federal Reserve released a paper in 2017 using a similar methodology to the IMF study but made specific tweaks to reflect the U.S. financial sector and the fact that additional financial regulations such as liquidity requirements also lower the probability of a financial crisis. The paper found that the level of capital that maximizes net economic benefits is slightly more than 13 percent to more than 26 percent of risk-weighted assets.80 With current equity capital levels around 12.5 percent, and regulatory requirements at less than that, the U.S. banking system is at best on the low end of this range and at worst below it.

In his farewell address in April 2017, former Federal Reserve Board of Governors member Daniel Tarullo stated:

In fact, one might conclude that a modest increase in these requirements—putting us a bit further from the bottom of the range—might be indicated. This conclusion is strengthened by the finding that, as bank capital levels fall below the lower end of ranges of the optimal trade-off, the chance of a financial crisis increases significantly, whereas no disproportionate increase in the cost of bank capital occurs as capital levels rise within this range.81

Tarullo explains what the data clearly show: For the sake of U.S. economic security, it makes sense to err on the side of too-high capital requirements rather than too low.

Former Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner is also concerned about current capital requirements. He argued in an October 2016 speech at the IMF and World Bank annual meetings that current capital requirements look high compared with the actual losses experienced during the 2007-2008 financial crisis, but those losses would have been much higher had the government not intervened extensively to prop up the withering financial sector.82 Academics including Anat Admati, Simon Johnson, William Cline, and Morris Goldstein have researched the question of adequate bank capitalization levels and have argued for years that more capital is needed.83 While the specific levels of capital that they prescribe differ, most fall within the general bounds of the IMF and Federal Reserve studies previously referenced.

The Treasury report even seems to agree on this point, despite offering a recommendation to loosen capital requirements. The report states, “While some modest further benefits could likely be realized, the continual ratcheting up of capital requirements is not a costless means of making the banking system safer.”84 While additional tools, such as long-term bail-in-able debt, are important and can play a role especially in the resolution of a complex firm, common equity capital has proved to be the best loss-absorbing option.

Policy recommendation

CAP recommends that regulators increase current capital and leverage ratio requirements to place the loss-absorbing capital cushions at the largest banks squarely within the socially optimal range. Moreover, these new capital requirements should be incorporated into the Federal Reserve’s annual CCAR stress-testing exercise.

Increase risk-based capital and leverage ratio requirements

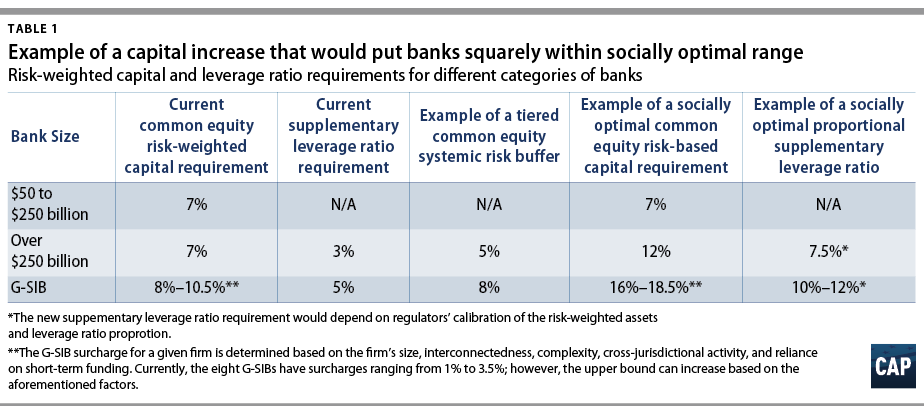

First, the appropriate banking regulators should initiate a rule-making to amend the risk-based capital requirements and leverage ratio requirements for all banks with more than $250 billion in assets in a tiered manner. Through this rule-making, the regulators should institute a new risk-weighted common-equity systemic risk capital buffer for banks with more than $250 billion in assets, with an even higher buffer for banks designated as G-SIBs to put capital requirements squarely in the middle of the socially optimal capital range.

Along with this risk-based capital increase, the regulators should raise the SLR and enhanced supplementary leverage ratio (eSLR) requirements for these institutions to be proportional with their new risk-weighted capital requirements. For example, a 5 percent risk-weighted buffer for banks with more than $250 billion in assets and an 8 percent buffer for G-SIBs would accomplish this goal. Using these numbers for the sake of argument, the new common-equity risk-weighted capital requirements for banks with more than $250 billion in assets, but not designated as G-SIBs, would be 12 percent. The new common-equity risk-weighted capital requirements for G-SIBs would be 16 percent to 18.5 percent or more, depending on the respective firm’s G-SIB surcharge.

Risk-based capital requirements will always be higher than leverage requirements to ensure that no one type of capital requirement is always binding. In this example, the supplementary leverage ratio would increase from 3 percent at the holding company level across banks with more than $250 billion in assets to roughly 7.5 percent, depending on the conversion factor chosen by regulators to keep the risk-weighted assets and leverage ratios in proportion. Currently, the eSLR does not vary across banks depending on their respective risk profiles, like the G-SIB surcharge does. Regulators should change that treatment and keep the leverage and risk-weighted capital requirements proportional at each bank. At G-SIBs, the new eSLR—currently at 5 percent at the holding company level—would increase in this example to roughly 10 percent through 12 percent depending on the conversion factor, as well as each individual firm’s new risk-weighted capital requirement.

The actual additional capital buffers need not be 5 percent and 8 percent exactly, but the capital requirements should accomplish the goal of moving the largest banks further away from the lower bound of the socially optimal range of capital. Banks typically fund themselves with capital exceeding the regulatory requirements, so when fully capitalized after phase-in, it is expected that banks would be a few percentage points above these new minimums. Banks should have five years to implement changes fully and should be able to do so primarily through retained earnings. Current requirements should not change at banks with $50 to $250 billion in assets, and the regulators should exercise discretion to subject or exempt banks within $50 billion above and below the $250 billion cutoff depending on a bank’s risk profile. Consideration should also be given to proposals to simplify capital requirements for community banks with less than $10 billion in assets. If regulators fail to act on this proposal, Congress should pass legislation directing regulators to increase both risk-weighted capital and leverage ratio requirements for banks with more than $250 billion in assets.

Integrate increased capital requirements into the CCAR

These new risk-weighted capital and leverage requirements for banks with more than $250 billion in assets and G-SIBs should be integrated into the post-stress capital minimums in the Fed’s annual CCAR stress-testing exercise. Currently, the additional capital buffers for the most systemically important banks, such as the G-SIB surcharge, are not integrated into the minimum post-stress capital requirements in the CCAR. Despite multiple intimations by former Federal Reserve Board of Governors member Tarullo and Federal Reserve Board Chair Janet Yellen, no rule to do so has yet been proposed.85 For example, a bank with $50 billion in assets and a G-SIB must both have a minimum of 4.5 percent common equity tier one capital after the adverse and severely adverse scenarios, despite having different regulatory capital requirements. If the G-SIB surcharge and the additional systemic risk capital buffers proposed in this section are integrated into the CCAR minimums, then the G-SIBs and banks with more than $250 billion in assets would have higher post-stress minimums than a bank with $50 billion in assets. In the context of integrating the G-SIB capital requirements into the stress tests, Tarullo and Yellen outlined the concept of a stress capital buffer, which would essentially incorporate the projected stress test losses for a given bank into the regulatory capital requirement for the following year. This is a sensible proposal that the Federal Reserve should proceed with and would be compatible with the additional systemic risk buffer proposed in this section. The integration of the G-SIB surcharge and the new systemic risk buffer into CCAR would align the regulatory capital requirements with the stress tests, reflecting the fact that the failure of a G-SIB would have higher costs to the system compared with the failure of a smaller institution.

Larger, more systemically important banks should have to internalize the cost of their potential failure and should face more stringent capital requirements accordingly. That principle should ring true in both the regulatory capital requirements and in stress testing.

Bank activities: The Volcker rule

Since its enactment, the Volcker rule has been under almost constant attack from conservative policymakers and the financial sector. Perhaps that is because its ambit and impact have the potential to be the most revolutionary: changing the very culture and profit-making centers of the largest financial institutions on Wall Street. More than three years after the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act, five financial regulators issued a final Volcker rule, implementing Section 619 of Dodd-Frank.86 The rule banned proprietary trading at banks and their affiliates as well as placed heavy restrictions on banks’ ability to own, invest, or sponsor hedge funds and private equity funds. Banning these highly risky activities at government-insured banks and their affiliates is a sensible financial stability safeguard; a bulwark against conflicts of interest and concentration of power; and an essential redirection of the culture of banks away from delivering big returns for traders and executives and in favor of investing in economic success of the broader American economy. It limits the possibility of large, rapid trading book losses; focuses banks on customer-facing activities such as market-making and underwriting; and removes banks from risky entanglements with hedge funds and private equity funds. The Volcker rule also protects market participants from the types of dealer-bank conflicts of interest that were commonplace prior to the financial crisis.

Risks of proprietary trading

Contrary to the oft-recited argument that proprietary trading had nothing to do with the financial crisis, it did play a critical role in causing the massive losses that shook the financial sector to its core—ultimately resulting in taxpayer-funded bailouts and the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression.87 When reviewing the causes and impact of the financial crisis, the BCBS highlighted, “Since the financial crisis began in mid-2007, the majority of losses and most of the buildup of leverage occurred in the trading book.”88 In January 2009, the Group of Thirty working group on financial reform—an international collection of private sector executives, government officials, and academics—released a report outlining a financial reform framework. The report noted the “…unanticipated and unsustainably large losses in proprietary trading…” in the United States and globally during the crisis and mentioned the additional risks posed by banks’ sponsorship of hedge funds.89

The authors of the Volcker rule’s legislative language, Sens. Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Carl Levin (D-MI), echo these points in a Harvard Journal on Legislation Policy essay. They outline the massive growth in banks’ trading books in the run-up to the crisis and the ensuing losses incurred when many of those swing-for-the-fence bets went south.90 In 2008, according to one survey of losses, banks lost roughly $230 billion in their trading books from collateralized debt obligations (CDOs).91 These complex structured securities were stuffed with bad mortgages, sliced into different tranches with varying risk profiles, and sold to investors. Banks typically built up large proprietary positions in the safest slice of the CDOs, known as the super-senior tranche, because the small return was not appealing to investors.

These super-senior exposures certainly constituted a proprietary position on banks’ trading books, as they had no intention to sell them at the market price. But when the underlying subprime mortgages collapsed, so did the CDOs—even the supposed safe, bank-held super-senior tranches. Banks also took on massive losses when they had to bail out the hedge funds, private equity funds, or off-balance-sheet vehicles they sponsored or when their investments in those funds failed.92 These activities represent an indirect way for banks to engage in proprietary trading or to gain downside exposure to proprietary trading, and the Volcker rule rightfully targeted them.

Even before the 2007-2008 financial crisis, there are lessons from modern financial sector history on the riskiness of proprietary trading and bank entanglement with hedge funds and private equity funds. The experiences of Long-Term Capital Management LP (LTCM) and JPMorgan Chase provide two examples.

Long-Term Capital Management LP

LTCM, a highly-leveraged hedge fund, almost precipitated a financial crisis when it was on the brink of failure in 1998. The fund leveraged $4 billion in net assets into $125 billion in gross assets, meaning it was massively leveraged at 30-to-1.93 The figure is even more jaw-dropping when factoring in the synthetic leverage that LTCM employed by using derivatives, which brought its total leverage exposure to about $1 trillion. The 1997 Asian financial crisis and the 1998 Russian financial crisis caused significant stress on the asset prices for LTCM’s arbitrage strategy.

Another arbitrage fund at Salomon Brothers failed during this period, and the fund liquidated its positions at steep losses, which put further pressure on LTCM’s portfolio. The FRBNY facilitated a private bailout of the fund in fall 1998 to prevent its impending failure.94 The bailout was necessary to prevent significant stress or potential failure at many of the largest Wall Street banks. These banks were not only exposed to LTCM through loans or derivatives contracts, but they had also directly invested in the hedge fund or mimicked LTCM’s strategies through their own respective proprietary trading desks.95 If LTCM had been forced to liquidate its portfolio at fire-sale prices, like Salomon Brothers did with its arbitrage fund, serious downward pressure would have been placed on the same positions held by systemically important banks that were mimicking LTCM’s strategies.

This near-crisis almost 20 years ago shows the dangers of allowing banks to become entangled with hedge funds through either direct investment, sponsorship, or mimicking through proprietary trading desks. While it is unclear whether highly leveraged hedge funds themselves still pose risks to financial stability today, the Volcker rule severely restricted the interconnection between banks and hedge funds to limit the possibility that these activities could cause problems in the future.96

JPMorgan Chase and the London Whale

JPMorgan Chase’s massive loss in the 2012 London Whale incident—which involved proprietary trading-type activities—is a more recent illustration of the risks that such activities can generate. JPMorgan’s Chief Investment Office (CIO) was responsible for investing excess bank deposits that were not lent out through the bank’s commercial banking operation.97 In 2006, the CIO began trading credit derivatives, allegedly to hedge against the bank’s credit risk. Overwhelming evidence acquired in the U.S. Senate Homeland Security Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations’ review of the London Whale trades suggests that this trading was proprietary in nature. An internal JPMorgan Audit Department report describes the CIO’s credit derivative trading activities as “proprietary position strategies,” and the portfolio, known as the synthetic credit portfolio (SCP), was under the umbrella of an overarching portfolio formerly known as the discretionary trading book—another name for proprietary trading.98 Furthermore, the CIO did not document or track the specific hedges for SCP activities, but it did carefully document the specific hedges for interest rate and mortgage-servicing activities.99

In 2012, some of these SCP trades executed by a trader nicknamed the London Whale resulted more than $6 billion in losses for JPMorgan Chase, revealing the riskiness of proprietary trading and shedding light on several risk-management, compliance, and regulatory shortcomings.100 In short, the SCP’s derivative trades were poorly masked proprietary trades—the very type of trade that the Volcker rule was later finalized to prevent. In late 2013, when the Volcker rule was set to be finalized, then-Treasury Secretary Jack Lew explicitly stated that the final rule was intended to prevent London Whale-style bets.101

Proprietary trading is highly risky and can clearly lead to sudden and severe losses. The Volcker rule’s main goal was to remove massive, systemically important bank holding companies and their affiliates from these speculative activities. The financial crisis made the necessity of this rule clear, but the London Whale incident serves as a useful reminder for all who question the Volcker rule’s necessity.

Impact of the Volcker rule

Since the passage of the Volcker rule in 2010 and its finalization and subsequent compliance date—in 2013 and 2015, respectively—it appears to be working as intended. Bank holding companies and their affiliates have shut down or sold off their proprietary trading desks and are in the process of selling off their noncompliant stakes in private funds, though regulators should be tougher in enforcing an efficient timeline for selling off these private fund investments.102

Furthermore, the information that regulators have released on Volcker rule compliance and trading metrics has been limited but encouraging. The Federal Reserve released value at risk (VaR) and Sharpe ratio data for banks that it supervises at a House Financial Services Committee hearing in March 2017.103 The VaR data showed no noticeable changes in risk-taking at the trading desks before and after the compliance period, while the Sharpe ratios demonstrate that trading desks are making their profits on new positions and making almost no profit on existing positions. The two metrics tell a story that trading desks at banks are still able to make markets for their clients and are making profits on bid-ask spread, fees, and commissions on new positions, not on the appreciation in price of existing positions.

However, far more transparency from regulators on Volcker rule compliance and impact is necessary. The fact that the Federal Reserve’s three-page update on these trading metrics is the only official update made public is deeply concerning—especially when regulators have already agreed to revisit the rule. How can regulators in good faith rewrite and potentially loosen a rule when they have not given the public data on how the rule is working? Regulators must provide the public with a full accounting of the law’s current impact and banks’ compliance with it before initiating any official rule-making on the Volcker rule, a topic that will be discussed further later in this section.

Efforts to roll back the Volcker rule

Congress and the Trump administration, echoing calls from the largest banks, have both made it clear that rolling back the Volcker rule is a priority. The Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, one of the main trade associations for the largest securities dealers, sent a letter to the Treasury Department endorsing full repeal of the Volcker rule and outlining recommended changes to the rule if full repeal was not an option.104 And the House of Representatives passed the Financial Choice Act in June 2017, with no Democrats voting yes.

As discussed above, the Financial Choice Act is the Republican plan to gut the Dodd-Frank Act, including a full repeal of the Volcker rule. If enacted, the plan would once again allow banks and their affiliates to make proprietary bets and invest heavily in hedge funds and private equity funds. In the first of the Treasury reports on financial regulation, the Treasury Department recommended a series of changes to the Volcker rule focused on “[r]educing regulatory burden,” “simplifying” the rule, and providing “increased flexibility.”105 The basic result of the Treasury recommendations—which include exempting smaller institutions from the rule; loosening the definition of proprietary trading; giving banks more flexibility in how they determine and comply with market-making requirements; and limiting compliance requirements to prove that a trading activity is hedging—would be a significantly less stringent rule with massive loopholes and limited teeth.

The bipartisan Senate banking bill also includes an outright exemption for banks with less than $10 billion in assets if the bank’s trading assets and liabilities account for less than 5 percent of its total assets. Unfortunately, this provision creates a massive loophole that would exempt a small depository institution that meets the aforementioned criteria from the Volcker rule, even if the depository is owned by a financial company of a larger size.106 Moreover, there is no limit to the number of exempted depository institutions that can be owned by the same financial holding company.107 Putting aside the necessity of this community bank exemption, if any changes are to be made for community banks, a far more tailored approach should be adopted. This approach should limit applicability only to banking organizations that have $10 billion or less in consolidated assets across all affiliates and subsidies; include activity restrictions on hedge fund and private equity fund activities commensurate with the limits on trading activities proposed in the bipartisan Senate banking bill; and provide anti-evasion tools for regulators to claw back the application of the full Volcker rule and regulation for a banking organization that appears to be undermining the intent of Congress by permitting genuine community banks—those that take deposits and make small-business, real estate, and automobile loans—to avoid the compliance obligations of the Volcker rule. In short, even after closing this noncommunity banks loophole, a blanket exemption for community banks is wholly inappropriate.

Justifications for weakening the Volcker rule fall short

The Treasury Department and Congress understand that they cannot simply call for changes to the Volcker rule, which would overwhelmingly benefit the largest financial firms, without claiming that there are serious problems with the current rule. But those claims fall short. Many banks that are now focused on standard flow trading to make markets for customers have had sustainable trading profits.108 Firms such as Goldman Sachs, which still appear to prefer complex trading that somewhat resembles precrisis, higher-risk trading, have been struggling compared with competitors engaged in volume-based flow trading.109

The banking industry’s stated justification for these changes is that the current Volcker rule regulation restricts banks’ ability to make markets in fixed-income securities—buying and selling Treasurys and corporate bonds for their customers—harming the liquidity that the financial system needs to function efficiently. According to the argument, with this diminished liquidity, the cost of transacting in fixed-income markets is higher, and higher costs slow economic growth. Investors would demand higher interest rates when lending to the U.S. government and corporations, charging a liquidity premium if they knew it would be more expensive to move in and out of their positions. Moreover, a lack of liquidity, especially during times of stress, would make the financial system more vulnerable during a crisis. Unfortunately for the Trump administration, Congress, and the largest banks, these claims have been thoroughly refuted by regulators and academics.

Furthermore, while dealer inventories of corporate bonds have declined since the financial crisis, this decline can be almost entirely explained by the decline in dealer inventories of private mortgage-backed securities—which counted as corporate bonds in inventory data. This means that the inventories of traditional corporate bonds are little changed and the Volcker rule has not caused dealers to pull back drastically from these markets.110 Liquidity metrics for the Treasury and corporate bond markets show that liquidity is well within historical norms, and by some measures better than precrisis levels.

The bid-ask spread, which represents the difference between the price at which a dealer is willing to buy a security and the price at which the dealer is willing to sell it, is one way to measure liquidity. It represents the cost associated with moving in and out of a position. The higher the bid-ask spread, the less liquidity there typically is for a given security. In essence, the dealer is charging a higher cost to hold the security knowing it will be more difficult to sell. The bid-ask spread in the corporate bond market and the Treasury market is now lower than precrisis levels, after hitting highs during the financial crisis.111

Another measure for market liquidity is the price impact of trades. If a trade significantly moves the price of a security, the next trade of that security will be more expensive. If a trader sells a security and the trade pushes the price down, the trader will receive a lower price for the next trade. Conversely, if a trader buys a security and pushes up the price significantly, the trader will have to pay a higher price on the next trade. In a liquid market, the price impacts are low. The current measures for the price impacts of trades in the corporate bond market are very low compared with precrisis levels.112

Trade size, another element of liquidity, has not recovered to precrisis levels.113 If traders think that large trades will have a big price impact, they may try to break up those trades, lowering the trade size metric and reflecting a less liquid market. But the decrease in the measures of price impact disproves this theory. Instead, the changing fixed-income market structure is likely the cause of smaller trade sizes. In reviewing these data points, as well as other data on corporate bond issuances and the regularity with which issues are traded, several studies over the past few years have concluded that fixed-income markets are liquid and that therefore, the Volcker rule has not harmed liquidity.114

Some arguments about market liquidity focus specifically on times of market stress and posit that while market liquidity may be healthy at the moment, the system is more vulnerable to a liquidity shock. However, the FRBNY has published research on this topic that shows that liquidity risk has declined drastically since the crisis and is currently low and stable.115 The FRBNY also looked at market liquidity during three case studies of market stress since 2013: the Treasury sell-off in 2013 known as the taper tantrum; the 2014 Treasury market flash rally; and the liquidation of Third Avenue Management LLC’s high-yield fund in 2015. The researchers found, “In all three cases, the degree of deterioration in market liquidity was within historical norms, suggesting that liquidity remained resilient.”116

In the December 2015 government appropriations bill, Congress included a provision directing the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to look at the Volcker rule’s impact on market liquidity, among other issues.117 The SEC report, published in August 2017 by the Division of Economic and Risk Analysis, found no deterioration of liquidity in the U.S. Treasury market, and that transaction costs in the corporate bond market have improved or remain steady.118 The report also found that corporate bond issuances are at record levels and trading activity is higher in the post-regulatory sample than in other time periods. Moreover, metrics such as the declining size of dealers’ balance sheets are consistent with nonregulatory-induced explanations, including changing market structure and a change in postcrisis dealer risk preferences. Overall, the congressionally-mandated SEC report is in line with the previously outlined academic research that finds no evidence that the Volcker rule has hindered liquidity.

The market liquidity justifications given for rolling back the Volcker rule, similar to the lending arguments given to justify rolling back capital requirements, have been repeatedly refuted by objective, high-quality studies and have little to no empirical evidence to back them up. Instead of proposing ways to loosen the firewall that the Volcker rule creates between customer-serving banks and other, higher-risk firms, regulators should explore ways to tighten the rule and to institutionalize a transparent regime focused on compliance with the rule and on its impacts.

Policy recommendations

CAP recommends taking several steps to bring implementation of the Volcker rule regulation in line with the original intent of the statute. These include establishing transparency, closing loopholes, addressing merchant banking activities, and further restricting compensation arrangements.

Establish transparency

First, before regulators undertake any revisions to the Volcker rule, they must provide detailed metrics on banks’ compliance with and the impact of the rule. In a 2015 letter to the regulators responsible for implementing the Volcker rule, Americans for Financial Reform outlined some of the necessary metrics needed for public transparency on the rule. These metrics, which should be released publicly both in the aggregate and on a desk-by-desk basis, include “reasonably expected near-term customer demand, profit and loss attribution, inventory turnover, inventory aging, and the volume and proportion of trades that are customer-facing.”119

The compensation arrangements for employees directly responsible for trading—and these employees’ supervisors—should also be disclosed. The regulators should codify this much-needed transparency in a quarterly public release. It is a violation of the public trust for regulators to revise a crucial component of financial reform—at the behest of the banking sector—without first being transparent about how the rule is functioning since it came into effect two years ago. If regulators fail to disclose this information regularly, Congress should pass legislation establishing a clear transparency regime around the Volcker rule’s implementation and enforcement.

Close loopholes

Regulators should also close remaining loopholes in the Volcker rule—including ending the exemptions for trading spot commodities and foreign currencies. This would simplify the rule, enhance its impact, and improve its adherence to statutory intent. The final Volcker rule, adopted in 2013, excluded the trading of physical commodities and currencies from the definition of “trading account.”120 But the statute, in Section 619 of the Dodd-Frank Act, did not explicitly exempt, nor did it intend to exempt, these types of trades.121 Some of the largest, most systemically important U.S. banks engage in the storing and trading of physical commodities. This trading carries risks that financial regulators may find hard to analyze and that can be proprietary in nature.

It should also be noted that the Volcker rule was included in the Dodd-Frank Act not just for financial stability purposes but also to limit the types of conflicts of interest witnessed during the crisis. For example, some banks can engage in the trading of physical commodities, such as oil or metals, due to the Volcker rule’s exemption in the definition of trading account, while also trading with and for their clients—clearly a scenario susceptible to the very conflicts of interest the Volcker rule was intended to address.

Furthermore, regulators stated that the exemption for trading in physical commodities and currency was included because the statute did not explicitly include these transactions. That justification misses the mark. The statute gives regulators the authority to include “any other security or financial instrument” in the definition of trading account, to be covered by the ban on proprietary trading.122 Regulators should use that statutory authority to close these loopholes—spot trading of commodities and currencies should be subject to the same restrictions as other covered forms of trading. Absent regulatory action, Congress should pass legislation directing regulators to close these loopholes.

Address merchant banking activities

Regulators should also address the fact that the current Volcker rule regulation does not cover bank investments in merchant banking activities. These activities, in which a bank takes an equity position in a nonfinancial company, can pose indistinguishable risks from impermissible private equity investments. Merchant banking activities expose the bank to credit risk, market risk, and other risks stemming from the activities conducted by the commercial company in which the bank has an equity stake. These investments can also be highly illiquid. Statements from the statute’s authors—and the rule’s namesake—former Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker, make it clear that regulators should have addressed merchant banking in the current rule.123

In September 2016, the Federal Reserve recognized the risks that merchant banking poses to bank holding companies and their affiliates in a report required by Section 620 of the Dodd-Frank Act.124 This report required regulators to analyze the different activities and investments that banks can currently engage in and make policy recommendations based on the review’s determination of the riskiness and appropriateness of those activities. The Federal Reserve recommended that Congress repeal the statutory provision established by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act—also known as the Financial Services Modernization Act—that allows banks to engage significantly in merchant banking activities.125 The Federal Reserve argued that eliminating this provision would help restore the traditional lines between banking and commerce and keep bank holding companies from engaging in an activity that could threaten their safety and soundness. It is clear that some banks are using their merchant bank activities to take risky proprietary positions.126 Similar evasion risks also exist with respect to bank sponsorship of business development companies (BDCs), which are a special type of mutual fund registered with the SEC.127

Based on the Federal Reserve’s findings, and the clear risks that private equity-style activities pose, regulators should explicitly state that merchant banking activities fall under the Volcker rule’s “high-risk assets” limitation on permitted activities, as Sens. Merkley and Levin intended.128 Categorizing merchant banking assets as high-risk assets would prohibit Volcker-covered bank holding companies and their affiliates from engaging in these activities. If regulators choose not to exercise this authority, Congress should pass legislation classifying merchant banking assets as high-risk assets or repeal the statutory provisions permitting merchant banking activities altogether. As an alternative, regulators or Congress could significantly increase the capital requirements for merchant banking activities. This is a less desirable approach compared with outright prohibition but would be an improvement over the status quo.

Regulators should also engage in close scrutiny of bank sponsorship or investment in BDCs to ensure that the prohibitions on private equity investing are not evaded through those vehicles, and Congress should require regulators to report on those findings.

Further restrict compensation arrangements