Introduction

In ever-increasing numbers, students enrolled in our nation’s colleges and universities are borrowing to meet educational expenses. As college costs rise, so too does the amount each student is borrowing. While federal student loans can be consolidated, these and private loans cannot be refinanced. If refinancing of student loans were available, borrowers could see significantly reduced monthly payments; lenders—including the federal government—could see increased repayment rates; and we all could see more economic activity, as a portion of each student-loan borrower’s income could be spent in other sectors of the economy or saved for larger purchases. In this issue brief, we review a number of proposals pending before Congress and recommend a number of elements that need to be included in a plan to permit student-loan refinancing.

Student-loan debt in America

Our higher-education financing system has become increasingly dependent on debt. Data from the Department of Education illustrate the precipitous growth of debt over recent years. In the 2011-12 academic year, 40 percent of undergraduates borrowed under federal student-loan programs—an increase of 18 percent since 2004 and 15 percent since 2008. More troubling is the fact that among those borrowing, the average amount borrowed in 2012 was nearly $7,800, up 44 percent from the 2004 amount of $5,400 and up 26 percent from the 2008 amount of $6,200. (see Figure 1) These figures represent just one year of borrowing; total borrowing levels for degree completion are likely to be substantially higher.

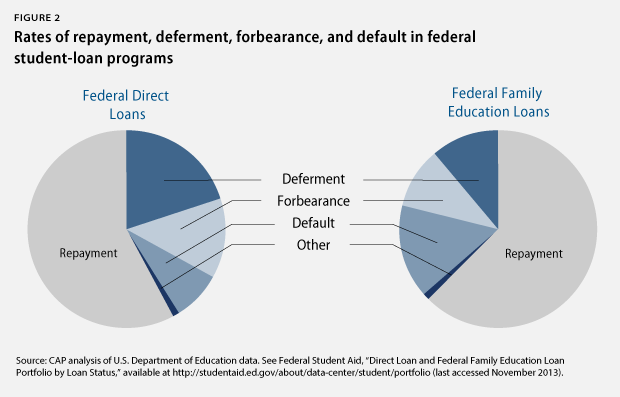

Consider this: It took 23 years for federal student-loan programs to lend their first $100 billion. Now, the federal government lends substantially more than that each year, and more than $1 trillion in federal student loans are outstanding. Of those outstanding loans, only 60 percent of borrowers in repayment were actually making their scheduled payments. The remaining 40 percent were in deferment, forbearance, or default, indicating that the borrowers are in distress. (see Figure 2)

Fluctuations in student interest rates and growing evidence of borrower distress in federal student-loan programs and the portfolios of private loan providers suggest that new and aggressive policy solutions should be enacted, ensuring that repayment terms remain manageable and students are able to make progress in retiring their debt. Allowing students to refinance their loan debt and take advantage of newly established lower rates could reduce the number of students in distress.

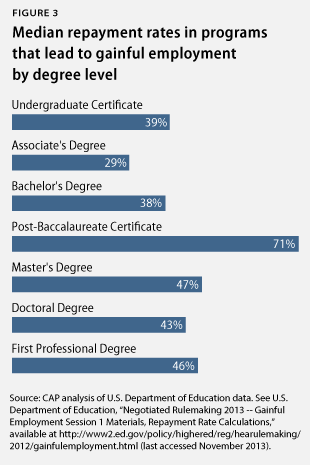

Further data released by the Department of Education provide clear evidence of the difficulty that many graduates are having in repaying their student loans. Repayment rates measure the share of students in a program that are able to make payments on their loans that reduce the principal balance by at least $1 in a given year. The Department of Education examined 1,930 associate’s degree programs at for-profit institutions of higher education and found a median repayment rate of 29 percent. This rate means that fewer than 3 in 10 students were able to make payments that reduced their loan balance and that half of the programs measured at that degree level had an even lower rate. Of 732 for-profit bachelor’s degree programs measured, the median repayment rate was 38 percent, while the 4,567 undergraduate certificate programs at all types of postsecondary institutions had a median rate of 39 percent. Graduate degree programs at for-profit institutions had median rates ranging from 43 percent to 47 percent. The program level with the highest median rate—71 percent—was the post-baccalaureate certificate level at all types of postsecondary institutions. (see Figure 3)

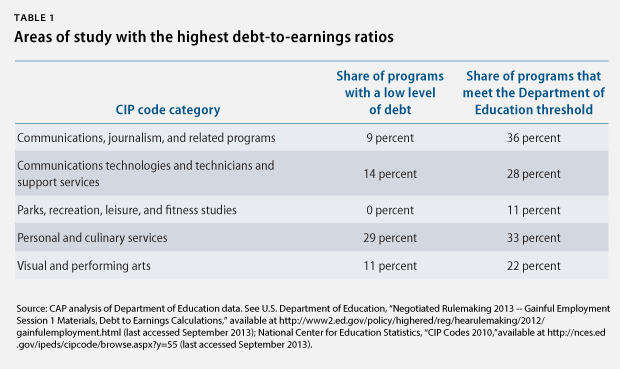

The Department of Education also calculated the debt-to-earnings ratios for graduates of programs that must, under the Higher Education Act of 1965, lead to gainful employment in a recognized occupation to ensure that student borrowers earn enough money to support the level of debt needed to pay for their education. The programs are organized by Classification of Instructional Programs, or CIP, codes, which are designed to track fields of study in postsecondary education. An analysis of programs at all levels by CIP code identified five areas in which students had the most trouble achieving earnings that covered their debt. In these areas of study, most programs were unable to pass the bare-minimum threshold that would allow students enrolled in them to continue to be eligible for federal student-aid programs, and even fewer programs had low levels of debt that would allow students to contribute to the economy.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York has become increasingly concerned about the levels of student-loan debt. In addition to the $1 trillion in outstanding federal student loans, the bank estimates that more than $200 billion in private education loans are outstanding. Information from one lender suggests that more than 9 percent of all loans in repayment are delinquent, with 4.6 percent delinquent by more than 90 days. An additional 3.5 percent of loans in repayment are in forbearance, and another 3.4 percent are charge-offs—they have been delinquent for so long that financial institutions no longer expect to collect them and consider them losses. This accounting suggests that more than $34 billion of outstanding private loans—15.9 percent—are distressed. An analysis by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau estimated that 7 million people are in default from a federal or private student loan.

As we observed in our report, “A Comprehensive Analysis of the Student-Loan Interest-Rate Changes that Are Being Considered by Congress,” student-loan interest rates have significantly fluctuated in recent years. This fluctuation reflects the changes in the cost of capital and in servicing student-loan debt overtime. In that analysis, we suggested that refinancing options could be provided to permit existing borrowers to move into the new approach to setting interest rates. This would allow borrowers that currently have interest rates as high as 8.25 percent to move down to the newly established rate. We suggested that it would be possible to defray some of the cost of refinancing by assessing borrowers a one-time fee or charging a slightly higher interest rate, similar to the current consolidation loans. Our recommendation was consistent with a report issued by CAP earlier this year in which we pointed out that homeowners, corporations, and state and local governments were taking advantage of the current historically low interest rates by refinancing their debt.

But student-loan debts are difficult to refinance. In the past, under the bank-based Federal Family Education Loan Program, lenders would occasionally take matters into their own hands, lowering interest rates below the maximum level set by law. Lenders often lowered the interest rates selectively—picking and choosing to which students they gave lower interest rates. The secretary of education had the authority to lower interest rates in order to encourage on-time repayment, but that authority—except as an incentive to encourage the use of Electronic Funds Transfer, or EFT—was eliminated in the Budget Control Act of 2011, making it impossible to address inequities in student-loan interest rates through executive action. Recognizing the severity of student-loan delinquency, federal bank regulators encouraged financial institutions to work with troubled private-loan borrowers.

Last fall, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau released a report that highlighted the fact that borrowers with private student loans have few repayment options, noting that, “By far, the most common concern communicated by borrowers is the difficulty they have negotiating a repayment plan with their servicer in periods of unemployment, underemployment, or financial hardship.” Borrowers also expressed frustration that there are few “workable” repayment plans or refinancing options available for private loans.

Providing student-loan borrowers the opportunity to refinance their debt is a way to solve a significant portion of the growing student-debt problem. Refinancing could significantly reduce monthly payments, increase repayment rates, and stimulate the economy by freeing up a portion of each student-loan borrower’s income that could be spent in other sectors of the economy or saved for larger purchases.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York has studied spending patterns and observed that those with student-loan debt are less likely to borrow to buy a home or car. In an April 2013 report, it concluded that for the first time in at least 10 years, 30-year-olds with no history of student loans were more likely to have home-secured debt than those with a history of student loans and that by the fourth quarter of 2012, student borrowers were actually less likely to hold auto debt than those with no student-loan debt.

Student-loan debt also holds back the nation’s housing recovery. Two million more adults ages 18 to 34 now live with their parents than before the recession. Each new household formed leads to an estimated $145,000 of economic activity, according to Moody’s Analytics. Student-loan debt may also be partially responsible for the decline in the national homeownership rate, which recently reached an 18-year low.

Addressing the problem

As important as these economic issues are for young adults, addressing the student-loan debt problem could boost trust in government among young Americans. Congress has begun to take note of the problems, with legislators offering four proposals to allow refinancing of existing student debt. Below, we describe these proposals and provide an analysis of each proposal. Taken together, these proposals provide a way forward to meaningfully address the need to reduce the monthly payments of millions of borrowers with existing student loans.

The Responsible Student Loan Solutions Act, proposed by Sen. Jack Reed (D-RI), Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Rep. John Tierney (D-MA)

Sens. Reed and Durbin and Rep. Tierney take a straightforward approach to addressing the refinancing of federally held or guaranteed student loans. The Responsible Student Loan Solutions Act was primarily designed to reset student-loan interest rates at the 91-day Treasury bill level, with an add-on percentage determined by the secretary of education to cover program administration and borrower benefits. Under the plan, interest rates for need-based, subsidized federal loans would be capped at a maximum of 6.8 percent. Rates for unsubsidized and parent loans would be capped at a maximum of 8.25 percent.

The Responsible Student Loan Solutions Act would also give the secretary of education the authority to reissue federal Stafford and PLUS loans at the same lower interest rate plus a markup for the cost of servicing. Under the bill, administrative costs can equal a maximum of 0.5 percent of the loan principal.

Federal Student Loan Refinancing Act, proposed by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY)

In the Federal Student Loan Refinancing Act, Sen. Gillibrand proposes permitting consolidation of all federal loans—Direct Loans and Federal Family Education Loans, whether held by a bank or the federal government—into a new loan at an interest rate of 4 percent or less. The secretary of education would notify borrowers with only Direct Loans of the consolidation at the lower interest rate within 90 days of enactment. For all other borrowers, the secretary would send a completed application for a consolidation based on information in the National Student Loan Data System within 90 days. The borrower would have six months to return the application for a consolidation loan.

If a borrower is in the process of earning a benefit at the time of consolidation—including through participation in Public Service Loan Forgiveness, reduced monthly payment programs, or other repayment plans—the borrower would remain on track to receive the benefit.

Student-loan refinancing proposal by Rep. Mark Pocan (D-WI)

In the House of Representatives, Rep. Pocan proposes legislation similar to that of Sen. Gillibrand. This bill, introduced in August 2013, provides refinancing options for student borrowers under the newly variable interest rate that was enacted in the Bipartisan Student Loan Certainty Act of 2013. That law reset the interest annually at the level of the 10-year Treasury note plus an add-on to offset costs associated with running the program; interest rates are capped based on loan type. Rep. Pocan’s proposal states that any student with Direct Loans would be allowed to refinance his or her loans to the rate that a new borrower faces at the time of modification. This new rate would be fixed until such time that the borrower chooses to modify his or her loans again.

Refinancing Education Funding to Invest, or REFI, for the Future Act, proposed by Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH)

Sen. Brown has proposed legislation that would address the issues specific to private student loans. Under Sen. Brown’s REFI for the Future Act, the secretary of the Treasury would have the ability to purchase private loans or participation interests in private loans or provide a liquidity backstop for private student loans. Appropriately structured, these purchases are designed to eliminate inefficiencies in the private student-loan market and accommodate reasonable refinancing opportunities for private student-loan borrowers.

Sen. Brown’s bill is modeled after the authority granted in the Ensuring Continued Student Loan Access Act. Under this act, the secretary of education purchased more than $110 billion in Federal Family Education Loans, or FFELs, over the course of three fiscal years, freeing up capital that could be used to make additional student loans.

If enacted, the REFI for the Future Act would encourage greater competition, innovation, and participation of private capital in a currently stagnant private student-loan refinancing market and create opportunities for private student-loan borrowers to take advantage of the current low interest rates, which will ensure that some borrowers pay rates that reflect their credit risk. By reducing the amount that private student-loan borrowers must pay, this plan can ensure they may pursue economically productive activities such as buying a home or starting a small business.

Streamlining loan information and payment mechanisms

Each of the three pieces of legislation that have been offered addresses a portion of the student-loan consolidation puzzle.

What is needed, however, is a solution that is easy for student-loan borrowers to navigate. Too often, student-loan borrowers do not know what kind of loan they have. While no bank-based FFELs were issued after July 1, 2010, students will still have difficulty determining which are Federal Direct Student Loans, which are FFELs, and which are truly private loans. For this reason, Congress needs to mandate that the secretary of education develop a portal that all student-loan borrowers can use to access information on their loans. This portal would largely be built with information from the National Student Loan Data System, or NSLDS. However, information about private student loans would be needed to augment the information in NSLDS. Requiring lenders to report all private student-loan disbursements to the secretary for inclusion in NSLDS would address this limitation and give policymakers and the public a more complete picture of how student borrowers are faring.

From this portal, each student-loan borrower could be provided with information about the range of consolidation and refinancing options available. In the case of federal student loans, borrowers should be provided the best-possible loan interest rate. In the case of borrowers that took out loans prior to July 1, 2013, if the rate they face is higher than current rates, the interest rate could be written down to the new level plus a small transaction fee. Borrowers that take out student loans under the new statutory formula should have their interest rate reset upon graduation if the interest rate would lower the weighted average of the loans taken out.

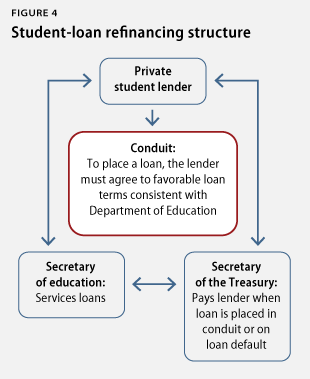

In the case of students with a mix of federal and private loans or just private loans, a model similar to that proposed by Sen. Brown seems appropriate. Under this approach, a conduit structure could be created into which lenders could place loans with the interest rate written down to assist borrowers. Loans placed in such a structure would have to have other terms and conditions to make them more like federal loans, such as death and disability insurance protections and the availability of deferments and forbearances and income-based repayment options. Upon a loan’s placement in the conduit, the lender would be paid a small percentage of the outstanding amount so that the federal government has a financial interest in the loan.

If a loan placed in the conduit becomes delinquent, the Treasury secretary would buy out the private lender for its remaining interest on the loan. The amount paid for the remaining interest would never be the full value of the loan but would reflect the lender holding a portion of the risk. (see Figure 4)

Such an approach would ensure that lenders are making private student loans with liquidity well beyond what would be available in the current market and provide the federal government with a performing asset if the lender needed to exercise its liquidity option.

In order to provide borrowers with the best possible interest rate, servicing risk needs to be minimized. For this reason, new passive collection mechanisms should be explored. Such a passive system could use the tax withholding system as the default mechanism for collecting student loans. Passive payment could include automatically enrolling eligible students in reduced monthly payment programs, such as Income-Based Repayment, or IBR; or Pay As You Earn, or PAYE—or, more extensively, could use the tax system to automatically deduct income-adjusted student-loan payments from gross earnings. This structure would also significantly reduce the servicing cost, allowing the funds currently used to support the collection system to be used for more constructive purposes such as increasing Pell Grants to reduce student indebtedness.

Permitting refinancing of student loans will lower returns for taxpayers, in the case of federal loans, and for investors, in the case of private loans, in the short term. As the New York Federal Reserve Bank concluded with regard to home mortgages, however, the macroeconomic effects of additional money in student-loan borrowers’ pockets will more than offset those losses. As a result, student-loan refinancing will likely not simply be a zero-sum transfer from taxpayers and investors to borrowers. Indeed, the evidence the New York Federal Reserve Bank has developed related to home mortgage loans has direct applicability; we believe, with respect to student loans, it means that borrowers relieved of some interest expenses will spend or invest those savings, stimulating economic growth.

Conclusion

Given the growing amount of student loans entering repayment, it is critically important to provide refinancing options for student-loan borrowers. An internal analysis by the Center for American Progress estimated that student-loan borrowers who currently face rates greater than 5 percent could save as much as $14 billion per year, resulting in significantly reduced monthly payments if they are able to refinance their student loans. Additionally, these borrowers likely would spend or save for larger purchases, increasing economic activity overall by as much as $21 billion. For this reason, it is critical that Congress move quickly to create opportunities for refinancing student loans while the cost of capital remains low.

David A. Bergeron is the Vice President for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress. Elizabeth Baylor is the Associate Director for Postsecondary Education at the Center. Joe Valenti is the Director of Asset Building at the Center.