“We started our lives here from zero,” recalled Mohammed, a refugee from Baghdad, Iraq, in a recent phone interview. Mohammed was resettled in Boise, Idaho, in 2015, with his wife Luma and their three children.1 Before they left Baghdad, Mohammed was a veterinarian and laboratory owner, while Luma had been a professor of mechanical engineering at Baghdad University for 12 years.2 Because Mohammed’s lab worked with foreign companies, he increasingly experienced personal threats and threats against his family. In 2010, when Mohammed and Luma felt it was no longer safe to stay in Baghdad, they applied for refugee status in the United States. Although they were resettled only a little more than three years ago, both have made impressive strides in rebuilding their lives: Mohammed now works as a senior microbiologist and Luma as both a lab instructor with Boise State University as well as a medical interpreter to help other Arabic-speaking refugees.

Najah is also a refugee from Iraq. She was resettled in Clarkston, Georgia, from Nineveh, a city near Mosul.3 When she first arrived with her children in 2009, she remembers feeling lost, because she left everything back in Iraq. Like Mohammed and Luma, Najah started out from scratch; unlike the couple, though, she had the disadvantage of knowing “very little English.” But after years living in the United States, she has made strides: Her English has improved, and she has learned to drive. Now, she is managing and teaching artisans at Peace of Thread, a local nonprofit organization that sells bags and purses made by refugee women.

Too often, stories such as these—of the successes and challenges of resettled refugees like Mohammed, Luma, and Najah—are left out of conversations about refugee policies.

Under the Trump administration, the refugee admissions ceiling4 has suffered dramatic cuts. For fiscal year 2019, the administration has set the refugee admissions ceiling at 30,000, the lowest in the nearly 40-year history of the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP).5 The total number of refugees actually admitted in fiscal year 2018 is even lower: Only about 22,500 refugees were admitted, the lowest number in more than a decade and only half of that year’s targeted 45,000 admissions.6 In short, even though the global need to resettle refugees is expected to rise 17 percent from 2018 to 2019, the United States will not be stepping up to the call—it will be stepping back.7

By undermining the refugee system, the Trump administration is disregarding two fundamental truths about this nation. First, for years, the United States has been a world leader in welcoming people who have fled violence and persecution and are seeking a safe place to call home. Since the USRAP was established in 1980, most administrations until now—regardless of political party—have paid heed to the global need for resettlement, thoughtfully calibrating the yearly admissions ceiling in consultation with Congress to cement the U.S. commitment.8 Second, U.S. communities have long benefited from the arrival of refugees each year.9 Refugees have unique stories and typically humble beginnings. Once they are resettled, they learn the new language, adjust to the different culture, and strive to establish a new life. But in the process, they also enrich and bring cultural vibrancy and diversity to their local communities.

This issue brief gives an overview of refugee arrivals and ceilings in the past two decades. It then presents the results from a nationally representative annual refugee survey, which provide a glimpse into the lives of refugees who arrived in the United States from fiscal years 2011 through 2015. The brief highlights the steps that newly resettled refugees are taking to rebuild their lives from scratch. It also shows how they have made notable advancements in just a few years. By lowering the ceiling on refugee admissions, the United States is breaking the tradition of giving hope, safety, and stability to refugees and is likely to miss out on many highly motivated and resilient individuals in the coming years.

The plummeting number of refugee admissions

The fiscal year 2019 refugee admissions ceiling is devastating for the refugee community in the United States and abroad. Since its first days in office, the Trump administration has taken calculated steps to severely restrict and weaken the U.S. refugee admissions program, the largest resettlement program in the world.10 Under the guise of strengthening national security, the administration first ordered a temporary 120-day ban on all refugees traveling to the United States, followed by a 90-day ban on refugees coming from 11 countries, including Syria and Somalia.11 The overt refugee admissions ban from all “high-risk” countries was lifted in early 2018, with the condition that refugees go through additional security on top of the multiple—and highly effective12—levels of screenings that have long been in place.13 Policies stifling the resettlement program are contrary to the beliefs of many national security experts who argue that strengthening the refugee system is in the national interest.14

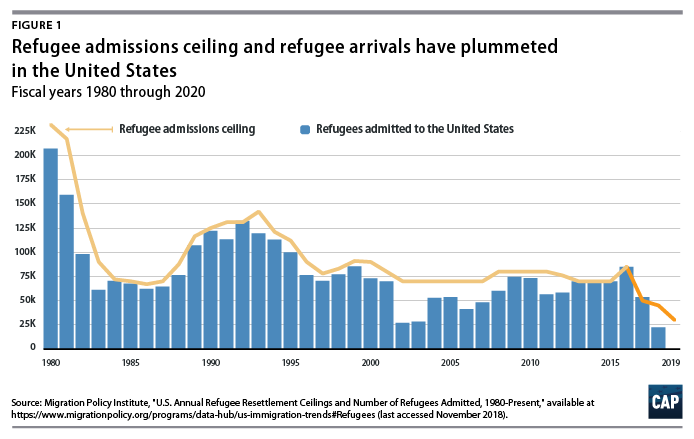

Four decades of refugee admissions data from the U.S. Department of State Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration illustrate the extent of the reduction in refugee arrivals as well as the inordinately low admissions ceiling set by the Trump administration.15 As Figure 1 shows, the refugee admissions ceiling was set at an average of 76,000 slots from fiscal years 1999 through 2016. In 2019, it was slashed to 30,000, a 64 percent reduction compared with 2016.

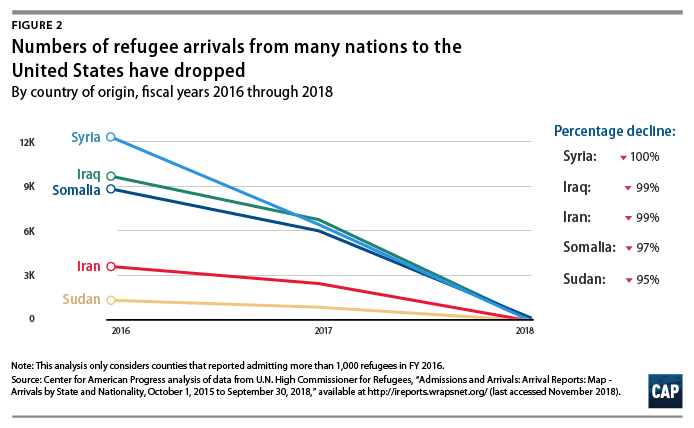

Similarly, refugee arrivals have dropped drastically from a high of nearly 85,000 in fiscal year 2016 to a low of 22,500 in fiscal year 2018—a 74 percent decrease. This is a far cry from the level of refugee admissions in the fiscal years ‘80s and ‘90s—more than 200,000 refugees were admitted in 1980 and more than 130,000 in 1992. (see Figure 1) The largest percentage drops in country arrivals since fiscal year 2016 are from Syria, Iran, Iraq, Somalia, and Sudan.16 (see Figure 2) For each country, the percentage decline was more than 95 percent when compared with 2016. The composition of resettled refugees also shifted. The monthly average Muslim refugee arrivals fell 93 percent in fiscal year 2018 under the Trump administration when compared with arrivals in the last few months of the Obama administration.17 Christian refugee arrivals are down by 64 percent; under the current administration, only two Syrian Christians have been admitted per month in fiscal year 2018. Because of the shrinking numbers of refugee arrivals, resettlement agencies and service providers are laying off workers or closing local offices all over the country.18 Such organizations have been irreplaceable in providing essential services to not only refugees but also the communities in which refugees live and these organizations operate.

Behind the plummeting numbers are the stories of refugees whose options for resettlement were limited to begin with and maybe even more so with the reduction in the admissions ceiling. Najah shared that two years ago, her husband applied to bring his sister from Turkey to the United States.19 Both Najah and her husband are citizens, and they can petition for a close relative to join them here. They are still desperately waiting to hear back about the application, as Najah’s sister-in-law is living a difficult life in Turkey but cannot return to Iraq—especially not to Ninevah, which has been extremely unsafe because of the presence of the Islamic State group in the region. So far, however, Najah has not heard anything about the application.

And when viewed in the context of the projected global need for resettlement, the United States’ refugee arrival numbers, as well as its 2019 ceiling on arrivals, look even worse.

The rising global need for resettlement

A recent U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees report highlights the rising global need for resettlement. It projects that this need will be higher in 2019 because of worsening security and human rights situations around the world, estimating that 1.4 million individuals will need to be resettled in 2019.20 Syrian nationals have the highest projected need for resettlement at 601,152, followed by those from the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan, at 163,448 and 158,474, respectively.21 These numbers represent just a sliver of the estimated 68.5 million people forcibly displaced around the world in 2017, including 25.4 million refugees, 40 million internally displaced people, and 3.1 million asylum-seekers.22 Furthermore, a growing number of Venezuelans are fleeing the worsening situation in their homeland; as many as 3 million Venezuelans have left the country in the past few years.23 The humanitarian crisis in Venezuela is a product of several factors, including a collapsing economy, lack of access to basic necessities, high rates of violence, and the tightening, increasingly authoritarian rule of leader Nicolás Maduro.24

Historically, only a fraction of the world’s refugees are permanently resettled in another country; in 2017, for example, less than 1 percent of the year’s 19.9 million refugees were resettled.25 The Trump administration’s reluctance to take this growing need into account will put more pressure on overburdened countries that are hosting the lion’s share of refugees. By the end of 2017, Turkey alone hosted 3.5 million refugees, followed by Pakistan and Uganda, who hosted around 1.4 million refugees each.26 Bangladesh saw a threefold jump in its refugee population due to the Rohingya people fleeing violence and persecution in Myanmar; by the end of 2017, it had 932,200 refugees, up from 276,200 at the beginning of the year. Keeping these host nations stable by assisting with resettlement efforts also serves a national security purpose for the United States.27

Recent refugee arrivals are faring well

Despite the Trump administration’s push to restrict the refugee program, there is ample evidence suggesting that refugees in the United States do well across a variety of socio-economic indicators.28

Survey data collected by the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) illustrates that a refugee’s journey toward integration, sometimes supported by trainings and services they may have received before or after relocating, starts as soon as they set foot in the country. The ORR has been conducting a survey of recent refugee arrivals as a part of its reporting requirement for Congress under the Refugee Act of 1980.29 The 2016 Annual Survey of Refugees (ASR) conducted by the ORR is a nationally representative survey that collects data on refugees who arrived in the United States from fiscal years 2011 through 2015 and captures their first few years in the country. This often overlooked but important data set, which has not been publicly available up until this year, aids in understanding how new arrivals are faring. An analysis of this survey finds that recently arrived refugees are working hard to improve their livelihoods; they are improving their English, getting jobs, and investing in their futures.30

These results are consistent with prior research findings that refugees, over time, have high labor force participation rates, improve their English-language skills, and decrease their public benefit use.31 Research also finds that they represent a net positive to the U.S. economy after living only eight years in the country.32 A recent unpublished HHS report, which the Trump administration rejected and suppressed and The New York Times later obtained, found that refugees contributed a net $63 billion to the national economy over the course of a decade.33

In terms of demographics, the ASR survey showed that nearly 22 percent of the recent arrivals were from Iraq; 17 percent from Burma; 12 percent from Bhutan; and 32 percent were from Somalia, Iran, Nepal, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Cuba, and Thailand combined. Regardless of ethnicity or religion, all of these refugees share painful, yet unique, circumstances that forced them to flee their countries. Their strength and resilience are key in helping them face the challenges of resettling in a foreign land.

Refugees’ English-language skills improve over a short time span

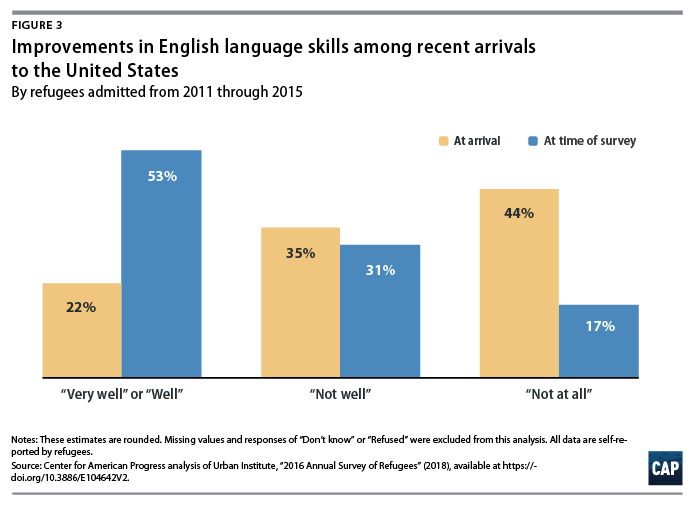

Learning a language takes time and is one of the biggest barriers that refugees face in the first few years after arrival. It is also one of the most important skills they must develop to navigate their lives in a new community. ASR results show that English-language skills among recent arrivals improved in a few years.

Nearly 44 percent of the refugees reported that they did not speak any English when they first arrived in the United States. However, that changed after they lived in the country for less than 6 1/2 years;34 only about 17 percent of refugees reported not knowing how to speak English at all at the time of the survey. Among refugees who did not speak any English upon arrival, nearly 62 percent reported that there had since been some improvement in their English-language skills. Among refugees who reported that they did not speak English well when they arrived, nearly 68 percent said they spoke English “well” or “very well” at the time of the survey.

As Figure 3 shows, 22 percent of the refugees reported speaking English “well” or “very well” when they first arrived. Comparatively, 53 percent reported speaking English “well” or “very well” after being in the United States for just a few years.

Mohammed and Luma both spoke English well when they arrived in the United States from Baghdad, which expedited their integration and job search.35 They quickly progressed from basic English classes and took an intensive English course offered by Boise State University to sharpen their language skills. The couple credited their English-language skills to their education in Baghdad, where most instruction from elementary school onward was in English.

Refugees are working and contributing to their communities

One of the main objectives of the USRAP is to ensure that refugees receive necessary resources to achieve “economic self-sufficiency” quickly.36 Yet, although refugees are initially provided limited, minimal support to start their new lives, they are expected to join the labor force as soon as possible and sustain themselves and their families.37 Therefore, it is not surprising that high percentages of refugees are in the labor force. According to the 2016 ASR, 67 percent of the refugees who are between ages 16 and 64 were in the labor force, meaning they were either working or looking for work. This is close to the U.S. labor force participation rate, which was nearly 74 percent, according to the 2012–2016 American Community Survey.38 More than 80 percent of refugee men were in the labor force, compared with 51 percent of refugee women. However, past research suggests that labor force participation among refugee women rises after living in the United States for more than a decade.39

Mohammed and Luma both started their careers in Boise as medical interpreters after the International Rescue Committee provided them with a language certificate. The process to get recertified as a veterinarian was complicated for Mohammed, who only has foreign training; with his immense dedication and assistance from Global Talent Idaho (GTI) and the U.S. Department of Labor, though, Mohammed was able to get his current job as a senior microbiologist. Luma was able to use her degree in engineering and connections provided by GTI to secure her job as a lab instructor for engineering students.

For Najah, working was the most important activity she did when she arrived, with learning English a close second. She was an elementary school teacher in Iraq for 11 years, but without good English skills, the first job she was able to get in the United States was as a cleaner. She took English as a second language classes and practiced with her children to improve her English. She has become a proficient seamstress at Peace of Thread, and she currently manages other refugee women and teaches them how to make and sell bags and purses.

Recent arrivals are a diverse group of people who are working in a variety of different industries across the United States. Among refugees who reported in the ASR that they have worked at some point since coming to the United States or were currently employed, 21 percent worked in manufacturing, 16 percent in hospitality, and 15 percent in retail and wholesale trade. The Fiscal Policy Institute’s study on refugee employment found that, among employers surveyed, refugee employees have higher retention rates compared with other workers, and this was true across industry sector and geography.40 For example, the turnover rates for refugees in the meatpacking plants included in the study was 25 percent, compared with 40 percent for all other workers.

Refugees are investing in their futures and putting down roots

Despite the adversities that refugees have faced, recent arrivals engage in a variety of activities with the goal of improving their work and language skills in order to obtain better jobs and establish themselves firmly in their communities.

“We want to be successful citizens,” Luma noted. But becoming successful after starting with nothing requires support and guidance. The International Rescue Committee, a resettlement organization, provided classes for Mohammed and Luma and shared information on how to apply for jobs, improve resumes, and write cover letters. An analysis of 2016 ASR data shows that among refugees between 16 and 64 years old, more than 14 percent went through a job training class in the previous year. Among refugees not enrolled in high school, nearly 27 percent were in an English-language training program in the past year.

Conclusion: America should get back to basics

Mohammed and Luma said they are appreciative of all the support they received when they first arrived—from the limited federal assistance that helped with food and rent before they became employed, to their dedicated caseworker who was always available to guide them through even the smallest issues. Luma mentioned that the kindness of people and organizations helped them through the most trying times during their resettlement. Mohammed remembered that they never felt alone. Today they are both working hard and giving back to the country they now call home.

But the United States is currently falling short of its commitment to protect refugees like Mohammed, Luma, and Najah. Worse, the fiscal year 2019 admissions ceiling means the country will no longer have the opportunity to be a part of many refugees’ journey to freedom and prosperity. The Trump administration must reverse its course of shrinking the resettlement program and re-establish the United States as a global leader in resettling refugees. In the years ahead, the United States will have to work hard and make a significant commitment to rebuild the refugee resettlement infrastructure harmed over the past two years of the Trump administration and resume its tradition of offering resettled refugees a new lease on life.

Silva Mathema is a senior policy analyst of Immigration Policy at the Center for American Progress.

The author would like to thank Mohammed, Luma, and Najah, who gave their invaluable time to answer questions. The author would also like to thank Tara Wolfson from the Idaho Office for Refugees and Denise Smith from Peace of Thread for connecting her with Mohammed, Luma, and Najah for interview. She is also grateful to Hamutal Bernstein and Carolyn Vilter from the Urban Institute for reviewing the draft and providing assistance with the ASR data, and Tom Jawetz and Philip E. Wolgin for their thoughtful input on the draft.