The fates of rural and urban Americans are intimately intertwined. Rural communities account for a significant portion of the U.S. population and economy. Approximately one-fifth of Americans live in rural areas, and 10 percent of the country’s gross domestic product is generated in nonmetropolitan counties.1 Moreover, rural areas are crucial sources of water, food, energy, and recreation for all Americans. Rural areas constitute 97 percent of America’s land mass, accounting for a large portion of the country’s vital natural resources.2

Despite the importance of rural communities to the health of the nation overall, federal policy has left many rural communities behind. Though some are thriving, rural areas overall have yet to match the employment levels reached prior to the 2008 recession, and deep poverty3 persists in many rural communities.4 Beyond barriers to jobs and economic opportunity, some rural areas also lack access to crucial services such as health care or the internet.5

Though some policymakers may be eager to tackle the challenges facing rural areas, discussions on this topic tend to make sweeping generalizations about the dynamics at work in these communities, leaving many Americans out of the conversation. The debate on how best to bring opportunity to rural America tends to focus on agricultural or postindustrial areas in the Midwest, often applying lessons learned or policy prescriptions to other U.S. regions without accounting for their differences. Moreover, the dominant narratives about rural America frequently neglect the experiences of black, Native American, and nonwhite Latinx populations—not to mention immigrants, LGBTQ people, and disabled people.

Rural America is not homogenous and should not be discussed or treated as such. In order to properly address the issues facing rural communities across the country, advocates and policymakers must understand the diverse nature of rural communities and the various systemic challenges they face. The problems facing the types of rural communities commonly portrayed in the national policy debate are urgent, but they should not overshadow the stories of rural residents in less visible regions with different demographic and economic characteristics.

This issue brief aims to broaden the picture of rural America in order to inform a more inclusive policy agenda for rural communities. First, the brief considers the industrial diversity of rural areas. It then discusses the challenges facing various marginalized groups in rural communities and highlights the varying experiences of three rural counties in different states.

What counts as a rural area?

Researchers disagree about the appropriate metric by which an area is defined as rural. The data for the Center for American Progress’ analysis were gathered from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Atlas of Rural and Small-Town America6 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service. Because much of the available data only include the metro-nonmetro delineation, this brief uses that delineation throughout. However, the authors expand those categories to incorporate degrees of ruralness. The urban-rural continuum defined in the Economic Research Service categorizes counties by population and proximity to cities, providing a relational dimension to the data.

The use of the metro-nonmetro delineation as a proxy for rurality has limitations. The delineation does not fully match the rural-urban definitions used by the Census Bureau, though there is some overlap. Another issue with using a binary delineation is that a county’s classification may change over the years due to fluctuations in population, making interpretations of rural areas over time difficult. Moreover, “rural” has a broader cultural meaning not fully captured by demographic data. For example, many Americans living in metropolitan areas describe their communities as rural.7 However one defines “rural,” these areas encompass a far more diverse swath of American communities than the mainstream debate acknowledges. Using the rural-urban continuum can provide insight into communities that may be inadequately described by the metro-nonmetro binary.

Rural areas exhibit industrial diversity

Most discussions about industry in rural America tend to revolve around the agriculture, manufacturing, and mining sectors. Some economists point to disruption in these industries as the reason for economic decline in rural America.8 The loss of manufacturing jobs due to globalization and automation, for example, has hit rural economies harder than the rest of the country.9 Conservative policymakers have villainized regulations of fossil fuels and greenhouse gas emissions because of their effect on mining communities.10

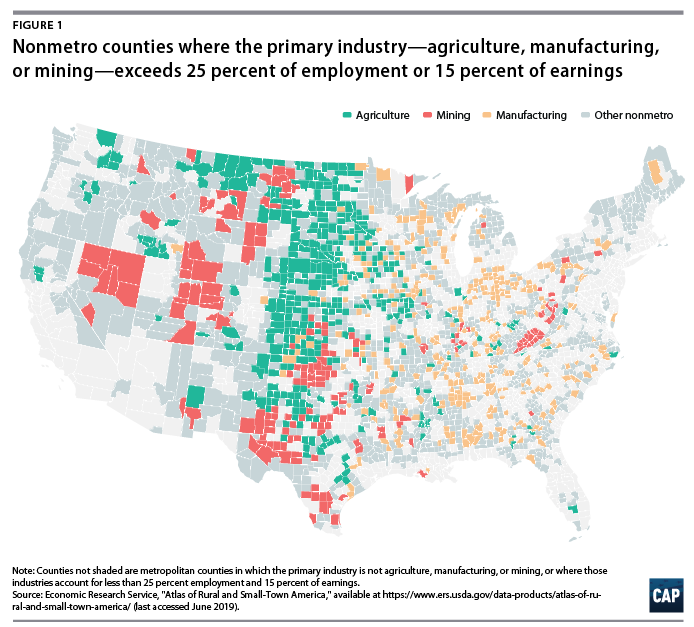

Indeed, many rural counties rely on mining, agriculture, or manufacturing. (see Figure 1) However, many rural counties have economies that are not based on these industries and do not have natural resources such as arable land or mineral deposits to participate in these industries or obtain a comparative advantage. Therefore, it is misguided for policymakers to present efforts to promote select industries as supporting the well-being of all rural Americans.

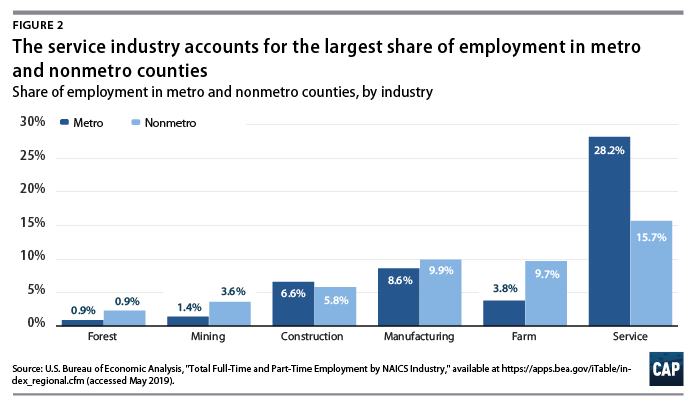

In short, while agriculture, manufacturing, and mining are important to many rural communities, they are not necessarily synonymous with rural America writ large. In fact, the service sector comprises the largest portion of employment in both metro and nonmetro economies overall, although metro areas’ share of employment in the service sector is almost double that of nonmetro areas. (see Figure 2) The agriculture sector does account for a larger share of employment in nonmetro counties, but manufacturing employment rates are similar between nonmetro and metro areas.

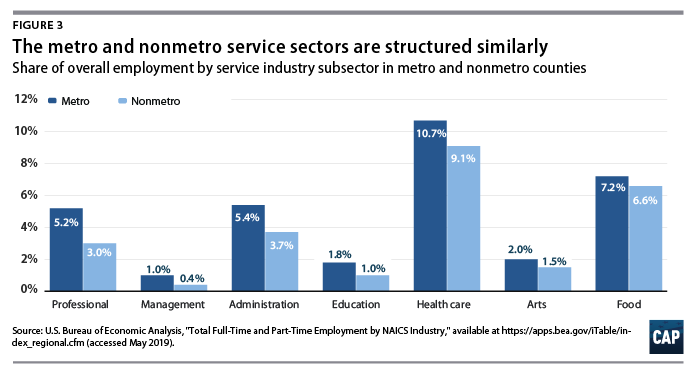

The service sector encompasses many industries and thus can be broken down into more specific categories. Overall, the service sectors in metro and nonmetro areas are fairly similar in structure. Figure 3 shows that the health care and food services industries dominate employment within the service sector in both areas. Across all service industries, metro employment exceeds nonmetro employment, but the differences are starker in the professional and administrative categories.

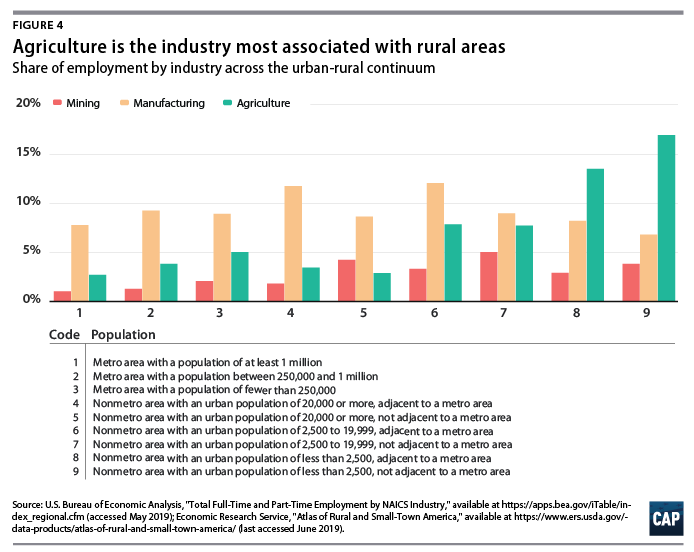

When examining industry employment by degrees of rurality, more pronounced differences appear across categories. Figure 4 shows that the sector most associated with rural areas is agriculture, which becomes essential to local economies that are closer to the rural end of the continuum. Among nonmetro counties, the manufacturing sector accounts for a larger share of employment in counties that are adjacent to metro areas, (see codes 4 and 6) while the agriculture sector is more prominent in smaller counties. (see codes 7 through 9) Mining employment is more common among nonmetro counties that are not adjacent to metro areas. (see codes 5 and 7)

The only sector that appears to be uniquely rural in nature is agriculture, which accounts for nearly 17 percent of employment in highly rural and remote areas. Agriculture-dependent economies are largely located in the heartland, running from the northern U.S. border through Montana and Nebraska and into northern Texas. Unfortunately, the agricultural sector is far from healthy—the projected farm income for 2019 is in the bottom quartile of all years since 1929.11 Bold policy solutions are needed to tackle corporate concentration and power, empower farmers to negotiate fairer prices, and ensure that farmers receive a fair share of the fruits of their labor.12

The importance of service industries across subcategories of rural economies suggests that effective policy solutions for rural areas must address the dynamics of this sector. For example, curbing the use of noncompete clauses would help raise wages and promote job mobility for many food service workers in rural and urban areas alike.13 Moreover, the decline of the manufacturing and mining industries need not spell doom for rural communities, especially if lawmakers pass policies that promote investments in emerging industries, such as green technology, in these areas. While transitioning from extractive industries to renewable energy or regenerative agriculture may be difficult and result in short-term economic stress, some thriving rural communities have proven that it is possible. One example is Colorado’s North Fork Valley, which has transitioned from a coal-based economy into a more diverse one that engages in tourism, clean energy, and outdoor recreation.14

Marginalized rural communities face significant challenges

When policymakers and the media discuss rural economic challenges, the communities they portray tend to lack diversity. Although rural America is proportionately less diverse than the country as a whole, these communities are still home to many people of color, immigrants, LGBTQ individuals, and disabled people. As policymakers consider solutions for and investments in rural areas, they must ensure that their agendas achieve equitable outcomes for marginalized rural communities.

People of color

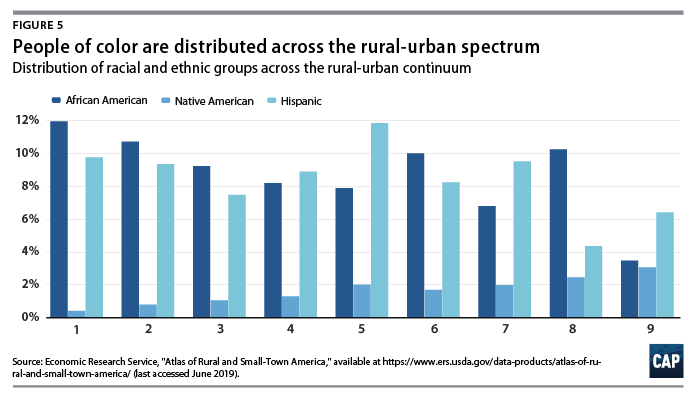

Significant populations of African Americans, Native Americans, and Latinx individuals live in rural areas across the country. While most communities of color are underrepresented in nonmetro areas overall, the racial urban-rural divide is more complicated. Figure 5 shows the distribution of African American, Latinx, and Native American populations across metro and nonmetro subcategories. Native Americans tend to live in the rural, nonmetro-adjacent counties. Latinx residents are distributed across the metro-nonmetro continuum, though a larger percentage reside in nonmetro counties that are not adjacent to metro areas. In particular, Latinx individuals in the Southwest and Native Americans in the Great Plains region tend to be clustered in nonmetropolitan counties.15 Native Americans living in rural areas have a lower quality of life compared with that of rural residents broadly—for example, nearly half of rural Native Americans reported having difficulty paying for major expenses in the past few years compared with about 40 percent of the entire rural population. Additionally, 27 percent of all rural Americans rate their quality of life as fair or poor compared with about 4 in 10 Native Americans in rural communities.16

One in 10 African Americans lives in a nonmetro area.17 Smaller counties that are adjacent to metro areas have, on average, as high a share of African American residents as medium and small metro areas. Rural African American populations are concentrated in the Southeast, where the legacy of Jim Crow laws has had lasting effects on economic mobility and where poverty persists at rates far higher than for the rest of the U.S. rural population.18 Compared with all rural Americans, African Americans living in rural areas are more likely to rate their quality of life as fair or poor, have difficulty accessing the internet, and struggle to pay off an unexpected expense.19

Immigrants

Over the past couple of decades, immigrants living in rural areas have made significant contributions to the vitality of their communities and local economies. One-fifth of growing rural areas owe their population growth entirely to immigrants. In the vast majority of rural areas experiencing population decline, immigration has played a key role in mitigating this trend.20 Yet, although immigrant communities have become the lifeblood of some rural areas, they face numerous challenges, from access to education to the disruption of families due to destructive immigration policies.21 For example, a workplace raid on a meatpacking plant in a small Tennessee town in 2018 resulted in the arrests of nearly 100 workers, tearing apart families and deeply wounding the rural community.22 Because immigrant communities are so integral to rural areas, immigration reforms and policies that support these communities are crucial to creating a thriving rural America.

LGBTQ people

As a recent study from the Movement Advancement Project (MAP) finds, many more rural Americans identify as LGBTQ than commonly assumed.23 MAP estimates that 15 percent to 20 percent of LGBT Americans live in rural areas, or approximately 2.9 million to 3.8 million people. Rural youth are also equally likely to identify as LGBT as their urban peers.

LGBTQ individuals living in rural areas can face structural barriers to a quality life. While health care access is an issue for rural Americans from all walks of life, 31 percent of LGBTQ Americans living in nonmetro areas report that finding an alternative source of health care if they were denied due to their sexuality or gender identity would be very difficult or impossible.24 LGBTQ people living in rural states are more vulnerable to employment discrimination or exclusion from key social institutions. .25 These factors likely contribute to the higher rate of poverty among small-town and rural households with same-sex couples compared with their different-sex counterparts.26 Despite these challenges, some rural LGBTQ Americans closely identify with their homes and way of life.27 Federal and state policies should recognize and support these Americans by providing resources such as community centers and specialized health care to rural LGBTQ communities and guaranteeing protections against discrimination in accommodations and employment.

Disabled people

For many rural residents, disability presents an additional structural barrier to prosperity.28 The disability rate in rural America is higher than it is in the total U.S. population.29 Disabled Americans face an uphill battle for care in rural areas, where hospital closures have left many people without access to health care.30 Disabled Americans who live in rural areas also tend to receive support services that are more expensive and less specialized than disabled residents of urban communities.31 These barriers may be part of the reason that employment rates for disabled people have yet to recover fully from the Great Recession.32 In fact, 70 percent of disabled, rural residents report that they would be unable to meet an unexpected $1,000 expense.33 Compounding difficulties with accessing health care and meeting their financial needs, disabled, rural residents are also more than twice as likely to report feeling lonely or isolated.34

Policymakers must resist stereotypes about rural areas that erase the struggles of marginalized rural communities, acknowledging that the intersections of racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, and ableism compound barriers to economic mobility and stability in rural areas.

A tale of three counties

Much of the recent public discourse35 about rural America has centered its focus on Iowa, including specific counties such as Adair County and Woodbury County. The “Today” show, for example,36 recently ventured out to Storm Lake, Iowa, and interviewed white farmers; even though the area’s population is nearly 20 percent Latinx, the images in the featured video were solely of white residents. The narrow focus of these pieces centers the struggles of white agricultural communities, exemplifying how public figures and media outlets portray rural America.

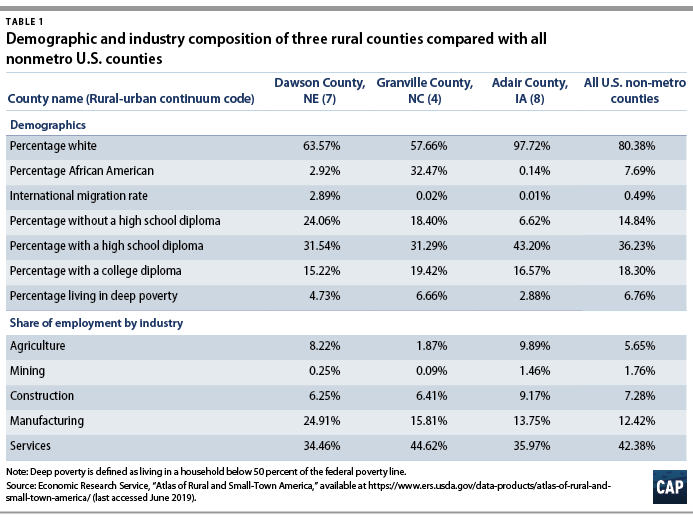

This reductive picture erases the many diverse, rural communities that face economic challenges—challenges that will likely continue to go unaddressed if the dominant narrative remains uncontested. Take, for example, Dawson County, Nebraska, and Granville County, North Carolina. Table 1 provides a comparison of these communities with Adair County, Iowa, which is currently receiving a notable amount of interest from the media and presidential candidates. While this CAP analysis classifies all three counties as nonmetropolitan, Dawson County and Adair County have smaller populations, and Adair County and Granville County are adjacent to metro areas.

Dawson County has a total population of about 24,000. The county seat is the micropolitan city—defined as having an urban population of between 10,000 and 50,000 residents—of Lexington, Nebraska, but it is not adjacent to any metropolitan county. As in Adair County, Dawson County’s agricultural employment constitutes a relatively large share of the local economy. However, nearly one-quarter of workers are employed in manufacturing at plants such as those operated by Tyson Foods37—a much larger share of manufacturing employment than in either Adair or Granville. And while in many respects Dawson may meet popular expectations of rurality, the county’s sizable immigrant population sets it apart from the dominant narrative.

Granville County, meanwhile, is home to about 60,000 people located on the northern border of North Carolina. It has an urban population of more than 20,000 people and is adjacent to the metropolitan county of Durham. Nearly one-third of Granville’s population is African American. While manufacturing represents 15 percent of employment in the county—which is home to a plant that manufactures cosmetics for Revlon—as in many rural counties, the service industry makes up more than 40 percent of employment. Although the Granville community is struggling more than some counties in Iowa, with a deep poverty rate more than twice that of Adair, policymakers and presidential candidates have spent little time speaking to the community’s needs.

Comparing these three counties, it is evident that the focus on Iowa and other Midwestern states distorts the reality of rural America. Rural America is not completely white, as the demographics of Adair County suggest, nor is it completely dependent on the agriculture sector. In fact, the service industry is the dominant industry across rural America. Highlighting the diversity of rural America allows for the application of appropriate policy solutions, encouraging policymakers to move beyond one-size-fits-all approaches that leave some communities behind.

Conclusion

Policymakers should keep the following three things in mind when discussing rural America’s challenges and successes:

- Counties are best described as falling on a continuum between highly urban and completely rural. Policy analysts and the media need to move away from the rural-urban dichotomy, as rural counties that are near metro areas are different from rural counties that are not. In some cases, rural counties near metro areas are more similar to urban counties than they are to rural counties farther from metro areas. The authors’ analysis showed little difference between the African American population in nonmetro counties adjacent to metro areas and in metro counties, and the manufacturing share of total employment was similar between nonmetro counties adjacent to metro areas and metro counties.

- While poverty and employment rates do differ across rural and urban counties, shares of employment by industry do not vary significantly across categories, with the exception of agriculture, which is associated with counties on the rural end of the spectrum. Employment in counties across the rural-urban continuum is primarily in the service industry; thus, policies to strengthen worker power and raise wages in the service sector would greatly benefit rural workers.

- Sizable populations of people of color; immigrants; LGBTQ people, including LGBTQ people of color; and disabled people live in rural areas. The structural and social barriers to prosperity for marginalized Americans in rural areas must be addressed in order to ensure that economic development in these areas is truly progressive.

Rural America is far more diverse economically, demographically, and in terms of industry than is frequently reported. This necessitates a more nuanced approach to narratives about rural America that accounts for its vibrant demographic and industrial diversity. Thus, any discussion of rural America needs to acknowledge these differences in order to inform policy solutions that address the needs of all rural Americans. A one-size-fits-all approach to rural development and advocacy will be ineffective and inequitable.

Olugbenga Ajilore is a senior economist at the Center for American Progress. Caius Z. Willingham is a research assistant for Economic Policy at the Center.

The authors would like to extend a special thanks to Katharine Ferguson and Mary Hendrickson.

Willingham previously published under the name Zoe Willingham.