The debate in Washington over security spending this year is being driven mostly by the Budget Control Act of 2011, the debt reduction deal that averted a government shutdown last summer. The law mandates about $1 trillion in cuts to federal government discretionary spending over 10 years beginning in fiscal year 2012, including $487 billion in Pentagon cuts. The law also mandates another $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction, by means of spending cuts, new revenues, or both over the next 10 years, with half taken from the Pentagon and half taken from discretionary spending on nondefense programs such as Medicare, foreign aid, and education.

This additional $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction, known as the “sequester,” came in to play after Congress failed to reach an agreement on how to legislate the deficit reduction at the end of last year, and it will take place on January 2, 2013 if Congress fails to act again. Much effort is being expended from many quarters to see that sequestration does not happen. The House of Representatives seems inclined to exempt the Pentagon from cuts while deepening them for the rest of the budget. For his part, Secretary of Defense Panetta has said that these cuts would be a “potential disaster, like shooting ourselves in the head.” But the heads of many other federal government agencies involved with sequestration, among them Jeffrey Zients of the Office of Management and Budget, have been reluctant to consider the consequences of the sequester.

The members of our Task Force agree with the near-universal consensus that sequestration is more about political maneuvering than sound budgeting practice. But we argue that the amount of cuts to the Pentagon budget mandated by both parts of the debt deal is readily achievable with no sacrifice to our security—if the cuts are done in a thoughtful manner over the next decade. We also agree that some of those savings in the U.S. defense budget should be redeployed to other parts of the federal government, specifically to those non-military programs that help our nation defend the homeland and prevent global crises from escalating into military confrontations.

This report delves deeply into these spending choices, but, first, let’s briefly run the numbers, beginning with the defense budget.

$1 trillion over 10 years

Several bipartisan commissions have produced frameworks for deficit reduction over a 10-year horizon; these commissions recommend Pentagon spending cuts approximating those mandated by the Budget Control Act, including sequestration. Among them is President Obama’s own National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, known as the “Bowles-Simpson Commission;” the commission headed by Alice Rivlin, President Clinton’s former director of the Office of Management and Budget and former Republican Sen. Pete Domenici; and the Sustainable Defense Task Force, of which several on our Task Force are members.

All three of the above proposals include specific Pentagon cuts that add up to approximately $1 trillion over the 10-year period mentioned above. These cuts make sense. As the largest item by far in both the discretionary federal budget and the security budget, Pentagon spending has the largest impact on the rebalancing equation. Since 2001 the United States has increased its military budget dramatically, paying for it with borrowed funds that have swelled the deficit, at the same time bringing us, in real terms (after accounting for inflation) to the highest levels of Pentagon spending since World War II.

Our current military expenditures account for nearly half of the world’s total. We spend as much as the next 17 countries—most of them our allies—put together, and we spend more in real terms now than we did on average during the Cold War, when we did have an adversary—the Soviet Union—who was spending about as much as we were and was an existential threat. Guaranteeing perfect security is impossible. But our dominance in every dimension of military power is clear. In recent years we have been building more “strategic depth” into this dominance without regard to its costs—both to our treasury and to our other priorities. A responsible rollback of our military budget is achievable with no impact on our security. This reduced spending trajectory is safely achievable for the following reasons:

- It would bring the military budget back to its inflation-adjusted level of FY 2006—close to the highest level since World War II and the second-to-last year of the George W. Bush administration. Was anyone worried that we were disarming ourselves then?

- The baseline military budget has grown in real terms for an unprecedented 13 straight years.

- The military’s blank check over this period has had predictable results in the form of massive waste. The estimate of cost growth in planned procurement spending is $74.4 billion over the last year alone, according to the Government Accountability Office, the investigative arm of Congress. This would cover the entire amount of next year’s sequestration, with $20 billion left over.(Responsible ways to manage the reductions are discussed in the three budgeting sections of this report beginning on page 39.)

- Over its 10-year lifespan, sequestration—plus the $487 billion in cuts already contained in the Budget Control Act—would reduce Pentagon spending plans by 33 percent, an amount that is in line with previous reductions. The last major defense budget drawdown, which occurred after the end of the Cold War through the administrations of presidents Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton, was 35 percent. Previous Republican administrations managed much larger reductions than the one mandated by the Budget Control Act: President Dwight D. Eisenhower reduced defense spending by 27 percent, and President Richard Nixon reduced it by 29 percent.

- The military increases of the past decade have been “paid for” by government borrowing, thereby increasing the deficit and national debt. Former Joint Chiefs of Staff Chair Mike Mullen has identified deficit reduction as a national security imperative, yet many of those who call themselves “deficit hawks” lose all interest in controlling the federal budget deficit when it comes to the military budget.

- The U.S. Defense Department has begun to justify its procurement plans by referring to “defense of the commons” and protection of the global economy, yet effectively policing the entire global commons is beyond the capacity of the United States and its partners. The United States is not the “Planet Earth Security Organization,” nor can it be. The attempt provokes competition by other great powers, leading to less security, not more.

- Reducing spending to 2006 levels will leave our military dominant in every dimension, including air power, sea power, and ground forces deployment, as well as in transport, infrastructure, communications, and intelligence.

Clearly, Congress can rebalance the U.S. defense budget responsibly while at the same time enhancing our overall national security. The American people agree. But beware of the military-industrial complex, which is hard at work trying to scare us into unsustainable defense spending.

Rebalancing our security by using a unified budget

This Task Force has made the case for the past eight years that a unified security budget would allow lawmakers to consider security spending as a unified whole, and also to use it as a basis for spending shifts in order to achieve a better balance among all the security tools. That’s why we were delighted to see unified security budgeting make its debut in the budget process in the current fiscal year. The Budget Control Act divided its mandated spending cuts in FY 2012 into two categories: “security,” which included the Departments of Defense, International Affairs, Homeland Security, and Veterans Affairs accounts, and “non-security,” which included all other discretionary account categories.

(As we have noted in the past, including the budget for Veterans Affairs as security spending is perfectly defensible because this spending is clearly a cost of military security. We have excluded it from our framework because spending to care for veterans, while a necessary and important consideration when undertaking wars of choice, does not contribute directly to our security.)

The plan for sequestration, however, divided the budget into funding for the military and funding for all other discretionary spending. Congressional budget maneuverings since then have switched back and forth between these two ways of categorizing spending. The House of Representatives in May passed legislation that would jettison the security/non-security categories to replace the sequester—which would require equal cuts to the military budget and the rest of discretionary spending—with a plan that would cut the rest of discretionary spending while leaving the military budget virtually untouched.

More often than not in the past year, the security/non-security frame of budgeting—unified security budgeting—has been proposed not as a way to rebalance security accounts but as a way to protect the military account at the expense of other parts of the security budget. These proposals would exact disproportionate cuts to the nonmilitary parts of the security budget, making the imbalance between military and nonmilitary resources even more extreme.

This is taking the potentially useful tool of unified security budgeting in the wrong direction. One case in point is what we call the “OCO effect.” In last year’s report, we raised concerns about how substantial a portion of the funding stream for International Affairs in the federal budget was being provided by the so-called Overseas Contingency Operations, or OCO, fund, which provides funds for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. A critical question, we said, was whether, as the wars wind down, this funding stream would be shifted to the core International Affairs budget, or simply cut. The appropriations process in Congress presents us with both of these possibilities this year. The Senate proposal makes the shift; the House’s makes the cut. The result: a $9.7 billion difference between the two in core funding for the International Affairs budget. In other words, 19.5 percent of the International Affairs budget, which funds such critical investments as counterinsurgency operations in Pakistan and the entirely civilian-run U.S. presence in Iraq, is riding on the post-war fortunes of the OCO account. Meanwhile the State Department will be expected to assume expanded responsibilities for U.S. engagement in both Iraq and Afghanistan just as it faces cuts alongside the rest of the discretionary section of the budget.

This kind of choice needs to be made strategically. In a speech at the Pentagon in January 2012, President Obama framed our historical moment as a turning point requiring a rebalancing of our priorities. Citing President Eisenhower’s admonition about “the need to maintain balance in and among national programs,” President Obama declared that “After a decade of war, and as we rebuild the source of our strength, at home and abroad, it’s time to restore that balance.”

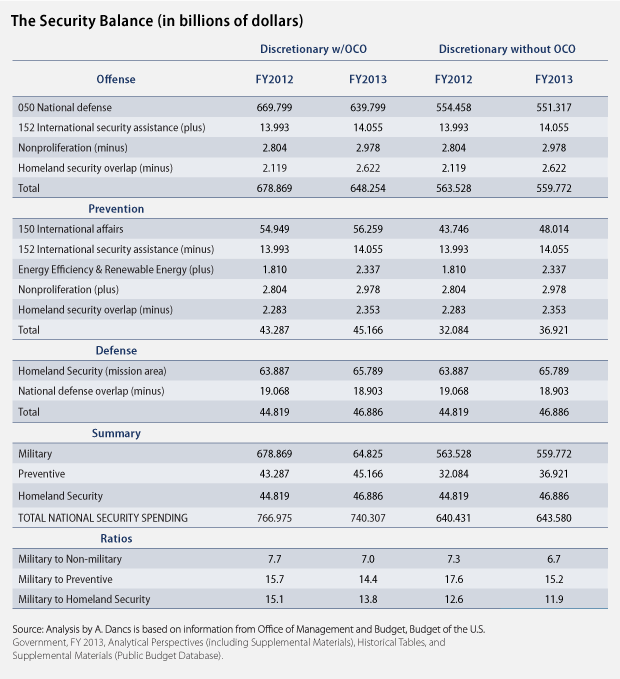

We agree. And we argue that the rebalancing the president seeks must include improving the current imbalance between the resources devoted to the military and nonmilitary components of our foreign and security policy. This balance tells, among other things, a story about us to the rest of the world. Our intensive international diplomatic efforts to keep Iran from becoming a nuclear state, for example, are undermined by a budget that is investing billions of dollars in new nuclear weapons designs of our own while at the same time shaving the resources we apply to nonmilitary nonproliferation. (see Table 1)

Rebalancing our security spending: The one-year horizon

President Obama’s budget request for FY 2013 does achieve some rebalancing of the security budget. For FY 2012 the request allocated $7.30 to the base military budget for every $1 devoted to the nonmilitary portions of the security budget. The FY 2013 budget narrowed this gap, allocating $6.70 for every dollar provided for nonmilitary security.

Our analysis of the president’s budget request reapportions federal budget categories to better differentiate military and nonmilitary security spending. According to our analysis, the president’s FY 2013 budget request decreases military spending in nominal terms by 5.5 percent, increases homeland security spending by 4.6 percent, and increases prevention spending by 4.3 percent. The FY 2012 request allocated 7.3 times as many resources to military security tools as to all nonmilitary tools put together. The FY 2013 request narrows that disparity slightly to 6.7 to 1. (See our report card on President Obama’s FY 2013 request below.)

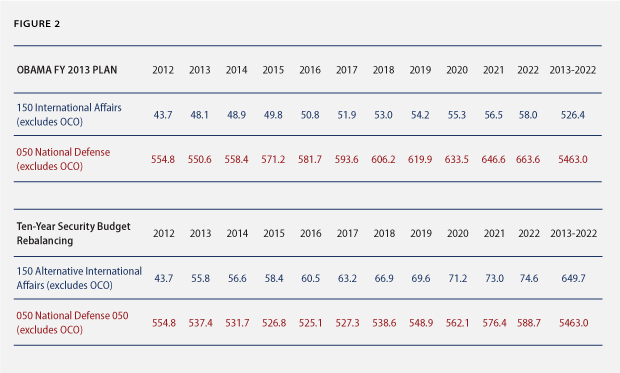

Our task force collaborated this year to produce an alternative security budget that shifts resources to produce a better balance between military and nonmilitary tools, taking into account the unique demands of the Budget Control Act—and taking advantage of the intense congressional debate about sequestration—to argue persuasively (we hope) on the need for our rebalanced unified security budget. (See Table 2 for a synopsis of our proposal.) Our two bottom lines:

- If sequestration proceeds, it must not be used to protect the military accounts at the expense of the rest of the security portfolio.

- Whether or not it proceeds, the total cuts to the military accounts specified by sequestration can be achieved without threatening our security if done in a rational manner.

Unified security budgeting must be used to balance security spending, not primarily to protect the military budget through disproportionate cuts in the rest of the security budget.

Our revisions to President Obama’s budget for offense in FY 2013 would set us on a path to achieving the $1 trillion in reductions over 10 years that, as we have argued, is readily achievable without sacrifice to our security. Our budget for defense essentially matches the president’s request, while shifting some priorities to shed wasteful programs and increase spending on underfunded parts of the homeland security mission, especially public health infrastructure. For FY 2013 our budget recommends Pentagon spending reductions of $71.8 billion and additions to the prevention budget of $28.1 billion. The resulting rebalancing is shown in Figure 2.

Our prevention budget makes relatively small, targeted additions to address specific shortfalls in such priority areas as nuclear nonproliferation, peacekeeping forces, and development assistance. We also recommend that the largest addition to the prevention budget be in the area of climate security. Unless we invest seriously to stabilize the climate, the resulting increased weather extremes will be, in the U.S. military’s words, “threat multipliers” for instability and conflict. In addition, these investments will pay dividends for job creation at home. The budgetary shifts we recommend will leave a remainder of $42.7 billion for deficit reduction and job-creating investment.

Rebalancing our security: The 10-year horizon

This year the focus of the budget debate has broadened to a 10-year horizon. From this perspective, unfortunately, the Obama administration’s budget plan does not improve the security balance. The gap between spending on offense and spending on prevention expands from about 10 to 1 in the president’s budget for FY 2012 to 11.5 to 1 in his plan for 2021.

Our Task Force plan outlines an alternative trajectory for spending on offense and prevention that would achieve the benchmark of $1 trillion in military cuts over 10 years. This framework provides $123 billion for international affairs over 10 years. It would increase spending on diplomacy during this period by 28 percent more than the president’s request, and increase spending on development and humanitarian assistance by 40 percent.

Overall, our plan would achieve a 20 percent increase in the international affairs budget, concentrated in the core missions of diplomacy and development. Significant, but hardly radical change is the result. Over this 10-year period, the gap between offense and prevention spending would narrow to a better balance of eight to one. Doomsday would not result.

This leaves a remainder of $440 billion over the next decade. In a late April speech at the AFL-CIO, President Obama outlined the budget shift he wanted to see as our nation transitions from its war footing: “It’s time to take some of the money that we spend on wars, use half of it to pay down our debt, and use the rest of it to do some nation-building here at home.” Our 10-year budget proposal is consistent with these priorities. It would allow for $200 billion for deficit reduction and about $240 billion for “nation-building here at home.”

Our recommendation for this latter purpose focuses on climate stabilization, a spending category that simultaneously advances the goals of national security, domestic nation-building, and job creation. In May of this year, Defense Secretary Panetta spoke about the “dramatic” effect from “rising sea level[s], to severe droughts, to the melting of the polar caps, to more frequent and devastating natural disasters” on our national security. He then talked about the Defense Department’s efforts to cut its own emissions.

Since his department is responsible for more of these emissions than any other single institution on the planet, these efforts are critical. But they are not sufficient. Stabilizing the climate will require emission-reducing actions across our economy, and across the world’s economy. Indeed, the investments necessary to address this security threat are also key to our economic security.

The components of climate stabilization—clean energy sources connected by a smart grid, clean transportation, and energy efficiency in our buildings and industrial processes—are foundational elements of the rapidly emerging global green economy. And a shift of funding from military to climate security would result in a net increase in employment. A 2011 study by economists at the University of Massachusetts found that $1 billion spent on the military generates about 11,000 jobs as compared to the nearly 17,000 jobs generated by the same amount invested in clean energy.

And since climate change can’t be solved by anything we do in the United States alone, helping the rest of the world with their transition to clean energy and transportation will be an investment in our own security. Our unified security budget would add $20 billion a year, or $200 billion over 10 years, in investments to stabilize the climate through domestic and global efforts to combat climate change.

We also recommend that the federal budget process include a climate change mission area. Until recently, the Office of Management and Budget was required to do an accounting of “Federal Climate Change Expenditures”—a climate change budget. Congress decided to suspend this requirement. It should reinstate it. In addition, federal expenditures on climate change should be presented in a unified way in the federal budget.

There is precedent for this. The Homeland Security Mission Area in the federal budget includes all federal programs, both within and outside the Department of Homeland Security, that contribute to the Homeland Security mission. Similarly, a new mission area, labeled Climate Change or Climate Security, can pull together in one place all the diverse federal programs contributing to this goal.

The time is now for a unified security budget

Before turning to our detailed budget analysis and then laying out our specific recommendations for a better security budget rebalance in the main pages of this report, we would like to reemphasize the complementary strategies that will help us get there. First, reform of the budget process is essential. Dysfunction has sunk Congress’s approval ratings to new lows. So in the section that follows we offer a range of options for reform in the realm of budgeting for security, arranged from modest to fundamental.

Second, tackling waste is equally important. The Obama administration has begun to incorporate goals for Pentagon efficiency savings in its budget projections. We make the case that these goals are merely scratching the surface of the savings that are possible.

Third, connecting security strategy to the budget process aligns strategies with the resources to execute them. If we are to achieve the benchmark of $1 trillion in military savings over 10 years, we will need to analyze the expanded set of military roles and missions that have helped to drive the extraordinary budget growth that has occurred in this century. And we will need to identify a revised set of missions that will provide for our security in a more cost-effective manner.

We will conclude our report with our three primary sections detailing our spending priorities on offense, defense, and prevention. This will demonstrate how rebalancing can and must shift resources toward preventive and truly defensive security measures. Since these measures are cheaper than the purely military approach to national security, our proposed unified security budget rebalances this spending, redeploying the money left over to reduce the federal budget deficit and to invest in those parts of the discretionary budget that can do more to stimulate the economy and create jobs—the two unheralded but truly essential components of our national security heretofore neglected by our current defense budgeting process.

Task force members

- Carl Conetta, co-director, Project on Defense Alternatives

- Anita Dancs, assistant professor of economics, Western New England University

- Kenneth Forsberg, senior manager for legislative affairs, InterAction: A United Voice for Global Change

- Lt. General (USA, Ret.) Robert G. Gard, Jr., chair, Board of Trustees, Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation

- Stephen Glain, journalist, author

- Robert Greenstein, founder and president, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- William D. Hartung, director, Arms and Security Initiative, Center on International Policy

- Christopher Hellman, senior research analyst, National Priorities Project

- William Johnstone, fellow, George Mason Center for Infrastructure Protection and Homeland Security

- Lawrence J. Korb, Senior Fellow, Center for American Progress

- Don Kraus, chief executive officer, Citizens for Global Solutions

- Miriam Pemberton, research fellow, Foreign Policy In Focus, Institute for Policy Studies

- Laura Peterson, senior policy analyst, Taxpayers for Common Sense

- Robert Pollin, co-director and professor of economics, Political Economics Research Institute, University of Massachusetts

- Kingston Reif, director of nuclear non-proliferation, Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation

- Lawrence Wilkerson, former chief of staff to the U.S. Secretary of State

- Cindy Williams, principal research scientist, Security Studies Program, Massachusetts Institute of Technology