Introduction and summary

Compared with other developed nations, the United States spends far more on health care yet performs no better on many measures of health.1 Moreover, health care spending in the United States continues to outpace economic growth. By 2026, $1 of every $5 spent in the American economy will go toward health care.2 One of the main reasons Americans receive relatively little value from their health care dollars is that the price paid for care is higher—and that cost is rising more rapidly than those in other industrialized nations.3 Prices for medical care have generally risen faster than overall inflation, even for common procedures such as appendectomies and knee replacements.4 Any serious effort to bend the cost curve must address the prices Americans currently pay for health care, including the price markups that result from insufficient competition in U.S. health care markets. Put simply, less competition leads to higher prices for care.

Health care industry firms involved in merger activity often claim that consolidation will result in greater efficiency, lower costs, and more coordinated patient care. However, research shows that such efficiency often does not materialize; even when it does, savings are not passed on to consumers.

Economic theory indicates that when many similarly sized firms are present in a market, their competition for consumers keeps product prices low. Concentrated markets, those with just a few competitors or in which a small number of firms control most of the sales, generally have higher prices. In concentrated markets, firms wield market power and have control over prices and supply. In some cases, concentrated markets arise naturally. The population of a rural county, for example, may be too small to support more than one medical clinic. In other cases, market power can fuel concentration. Firms may drive out rivals by providing better care or lower prices; by developing loyalty to their brand; or by engaging in anti-competitive, unfair business practices. Another way markets can become concentrated over time is through consolidation, as competitors combine to form a single firm through mergers or acquisitions.

The U.S. health care system is riddled with highly concentrated markets, and consolidation is a major driving force. There are some key factors contributing to consolidation: Physicians’ practice groups have grown larger over time;5 three firms now account for two-thirds of pharmacy benefit management—the third-party administrators for prescription drug programs for insurers and other end payers; and more than half the pharmacy market is controlled by the top five firms.6 Based on federal antitrust regulators’ standards, in 9 in 10 metropolitan areas, the hospital market is highly concentrated.7 Health care industry watchers have noted that consolidation is picking up: The consultancy PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) declared that 2017 marked the “[r]esurgence of megadeals,” and the advisory firm Kaufman Hall declared it the year mergers and acquisitions “shook the healthcare landscape.”8

In addition to consolidation between like firms—hospitals acquiring other hospitals or pharmacy chains merging together—the health care sector is also experiencing increased vertical consolidation, that is, integration among companies that provide different sets of services.

The boom of vertical mergers starting in the mid-1990s was driven by hospitals and physician groups joining to form integrated provider systems.9 Today’s headline-making deals involve all facets of the health care sector. This fall, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and state regulators gave their blessing to the $69 billion merger between the insurer Aetna and CVS Health, whose business includes retail, health clinics, pharmacy services, and pharmacy benefits management.10 Among other recently announced vertical tie-ups are insurers such as Cigna and pharmacy benefit managers like Express Scripts and insurers and providers—United and DaVita. In addition to mergers, vertical integration also occurs as existing firms venture into new lines of business. A number of health system giants, including Partners HealthCare in Boston and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, run hospitals and offer insurance plans.11 More recently, a group of health systems have banded together to launch their own nonprofit generic drug supplier, Civica Rx, to secure lower prices and steadier supply for their hospitals in response to the growing market power of generics manufacturers.12 Even technology giants are wading into health care management. Google announced it is teaming up with insurer Oscar, and Amazon joined with Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase & Co. to tackle health care costs.13

While examples of concentration in the health care sector are rife, this report focuses on health care providers, namely hospitals and physician practices, and the consequences of consolidation in that arena. In 2016, the United States spent $1.7 trillion on hospital care and physician and clinical services, which together accounted for more than half, or 52 percent, of the nation’s health expenditures that year.14 This report discusses how health care provider markets are becoming increasingly concentrated, as well as the implications for both payers and patients.

Tackling the harms of concentrated provider markets will require that federal and state antitrust authorities slow the pace of consolidation and that other policymakers step in to protect consumers in markets lacking competition. The final section of this report proposes changes in three areas to address the problem:

- Strengthen enforcement by antitrust agencies.

- Boost competition among providers.

- Bring down prices in already concentrated markets.

Progress in all three of these areas is crucial. Many popular policies to promote competition—hospital price transparency and rural telehealth, for example—do not directly address the elephant in the room: market power. The effectiveness of solutions in the first two categories relies on the ability of purchasers of health care—that is, insurers, employers, and patients—to make choices in a competitive environment, which many areas of the country lack. Conversely, regulations that cap provider rates prevent monopoly-level pricing but do not generate competition.

Robust competition and a dynamic market can drive innovation and improvements in health care. Mergers are ultimately a business decision, however, and policymakers should be doing do more to ensure consumers’ interests are protected.

Health care markets have become increasingly concentrated

When a small number of firms control most of the business in a market, that market is said to be concentrated. In health care, this could be a city with just two health care systems or a hospital that accounts for 60 percent of a city’s inpatient admissions. High levels of market concentration alone are no guarantee of noncompetitive outcomes, but a large body of research documents well-defined circumstances where that is the case.15 A common measure of concentration known as the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is calculated from each firm’s share of a market. At the high end, a market with a monopolist, the HHI score is 10,000; a market split evenly between two firms has an HHI of 5,000; and a market with 10 equally sized firms would have an HHI of 1,000. The federal governments’ chief antitrust enforcement agencies, the DOJ and Federal Trade Commission (FTC), define highly concentrated markets as those with an HHI above 2,500, a level that results from, among other possible configurations, four firms each holding a quarter of the market.

Using the HHI as a measure, concentration has increased among hospitals, specialty physicians, and primary care physicians over the last decade.16 One study found that 90 percent of U.S. metropolitan areas were highly concentrated for hospitals; 39 percent for primary care physicians; and 65 percent for specialty physicians.17 Another study, which looked at the average concentration across all provider types, found that 90 percent of metropolitan areas met or exceeded the 2,500 HHI threshold for a highly concentrated market.18

Rural areas of the country also suffer from scant competition, though concentration in those communities often results from too few providers rather than consolidation. About 1 in 5 rural counties has no hospital at all, and half lack a hospital with obstetric services. 19 In 1980, the country had 5,830 community hospitals;20 the most recent count is 4,840.21 Moreover, the number of hospitals in the United States has declined over the last three decades because of closures, mergers, and acquisitions.

Concentration leads to higher prices but not better care

There is staggering variation in hospital prices across markets, across hospitals within markets, and even between payers within hospitals, suggesting that hospitals are charging noncompetitive rates—in other words, whatever the market will bear.22 In metropolitan areas that experienced hospital consolidation from 2010 through 2013, hospital prices generally rose more sharply than in other areas of the same state.23 Blue Cross Blue Shield claims data show that the price of a knee replacement ranged from a low of $16,772 to a high of $61,585 among Dallas hospitals.24 Another study by the Minnesota Department of Health found that prices varied as much as sevenfold for a single procedure within a single hospital, depending on the payer.25 And although hospital executives often blame higher private rates on underpayment by public insurance programs, hospital price data do not support this theory.26 On the contrary, higher Medicare rates appear to be associated with higher commercial rates. 27

A report commissioned by the American Hospital Association (AHA) argues that “scale is necessary to accommodate the substantial requirements for data, IT infrastructure, and underlying systems to enable ‘accountable care.’”28 There is little evidence, however, to show that mergers have led to better care or lower costs for patients. A PwC analysis found that larger health care systems generally have neither lower costs nor better-quality scores.29 A retrospective FTC analysis of the Chicago-area merger between Highland Park Hospital and Evanston Northwestern Healthcare found large price increases and no strong proof that the transaction led to clinical improvements.30

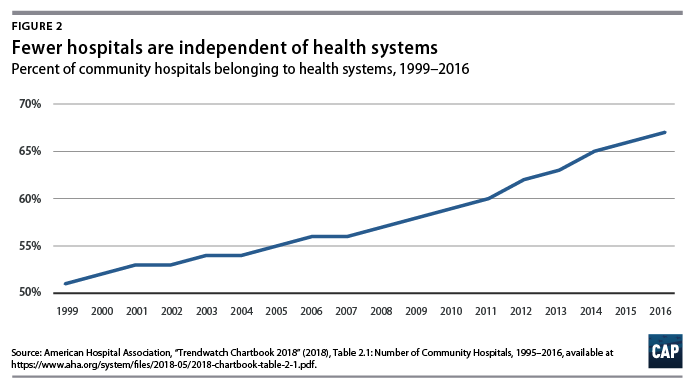

In fact, consolidation is one of the major forces driving hospital prices up. Two-thirds of community hospitals now belong to a multiprovider health system, compared with just half two decades ago.31 (see Figure 2) Empirical studies have shown that hospital mergers lead to prices that are 10 percent to 40 percent higher.32 This phenomenon is not limited to for-profit hospitals; nonprofit hospitals also raise their prices in more concentrated markets.33 Studies suggest that even cross-market hospital mergers boost hospital systems’ bargaining power vis-a-vis insurers. Hospitals that are involved in mergers in different areas of the same state end up with prices that are 6 percent to 10 percent higher.34

The ultimate cost of care depends on the larger health care market ecosystem, including the balance of provider-insurer bargaining power. Even in cases where hospitals can reduce costs through scale, those potential savings may be retained by hospitals or captured by insurers, never reaching the consumer. One study found that although acquired hospitals have 1.5 percent lower costs, this effect stems from the merged firm’s increased buying power rather than greater efficiency.35 Hospitals’ marked-up list prices hit uninsured and out-of-network patients especially hard, because these groups are often billed the full amount, rather than the discounted rates negotiated by insurers. The role of insurer versus hospital market power in setting the price for services was described by economist Glenn Melnick in a recent New York Times op-ed:

Data from California illustrate how hospitals have exploited this situation. From 2002 to 2016, total billed charges by hospitals rose by a staggering $263 billion, to $386 billion, even though the number of patients admitted did not increase. Billed charges to health plans grew from $6,900 per day to over $19,500 per day. This astronomical run-up in billed charges gave California hospitals leverage to demand and receive much higher prices for in-network patients, too. The average price paid by health plans to hospitals for all care grew almost 200 percent — to $7,200 per day from $2,500.

In effect, they [the hospitals] could threaten: Pay us $7,200 per day to sign a contract or $19,500 per day for emergency admissions without a contract.36

In situations where insurers have the upper hand, they can exert downward pressure on provider prices. Insurers appear to have the greatest success negotiating down hospital and specialist rates in markets with high levels of both provider and insurer concentration. However, in such cases, issuers may not face pressure to pass the benefit of lower prices on to consumers via lower premiums.37

Though physician markets have not been studied as closely as hospital competition, largely due to a lack of comprehensive data until recently,38 existing research shows that concentrated physician markets also lead to higher costs. The size of physician practices appears to be growing, with physicians increasingly practicing in multispecialty groups.39 More highly concentrated physician markets not only have higher prices for office visits but also experience more rapid price growth.40 For example, the price of a primary care visit in the nation’s most highly concentrated markets was about 23 percent higher than the national average.41 A study of California’s health care system attributed a 9 percent increase in prices for specialists and a 5 percent increase in prices for primary care to hospitals’ vertical integration that occurred from 2013 through 2016.42

The evidence on the relationship between practice size and quality of care is mixed. On the one hand, larger practices may have greater resources and are quicker to adopt new technologies and care coordination strategies.43 On the other hand, small practices may be nimbler in adapting care improvements. At a 2014 FTC workshop, Patrick Courneya shared his perspective on small practices as the medical director for Minnesota-based HealthPartners system:

The other thing that’s important in our experience is that we have seen groups at all points along the spectrum, some of our highest performing groups are actually the smallest. They have agility and just enough information about their patient population to drive better performance. And they’re actually among the most cost-efficient groups that we use as well. Those smaller groups actually have greater flexibility in identifying high-cost hospitals or even high-cost behaviors within emergency rooms and other things, and can go to those referral providers and actually talk to them about what the problem is.44

In this vein, one study found that larger physician groups have higher risk-adjusted spending per high-need beneficiary and higher hospital readmission rates.45 Another study found that concentration among cardiologists was associated with not only higher utilization and higher expenditures, but also increased mortality.46

Antitrust enforcers are not slowing consolidation

Growing market concentration is not unique to the health care sector. Market power has risen across the U.S. economy, resulting in higher profits and less innovation.47 At the same time, antitrust enforcement has grown more lax, with research showing a sharp change in the distribution of DOJ and FTC enforcement toward only the most concentrated industries.48

The evolution of the FTC and DOJ’s Horizontal Merger Guidelines reflects this increasingly permissive view of market concentration.49 The guidelines lay out HHI thresholds for evaluating whether a merger between firms competing in the same market is presumed to produce anti-competitive effects. In practice, however, the agencies’ bar for challenges has crept up over time,50 leading the agencies to formally raise the HHI thresholds in the guidelines’ 2010 revision. The FTC has virtually abandoned challenges of mergers resulting in highly concentrated markets—an HHI of more than 2,500—thereby establishing a de facto safe harbor for consolidation activity under that level.51 Even in markets with higher levels of concentration, the FTC has been more permissive of consolidation than its merger guidelines seem to indicate.52

The FTC has the chief antitrust enforcement power over health care providers, and its history of health care challenges has had its ups and downs. The FTC lost several cases in the mid- to late-1990s, a period when, in the words of former FTC Commissioner Julie Brill, the FTC’s “hospital merger work had hit an iceberg.”53 In response, the agency invested heavily in a retrospective analysis of hospital mergers to amass evidence on the effects of consolidation and revamped its strategy for future enforcement cases. While the FTC’s success in blocking health care mergers has picked up over the last two decades, the unflagging pace of consolidation in the industry suggests that the agency’s efforts are having little deterrent effect.

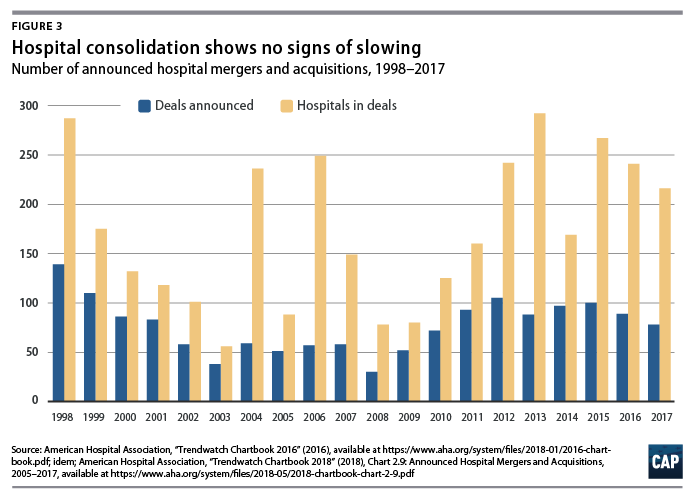

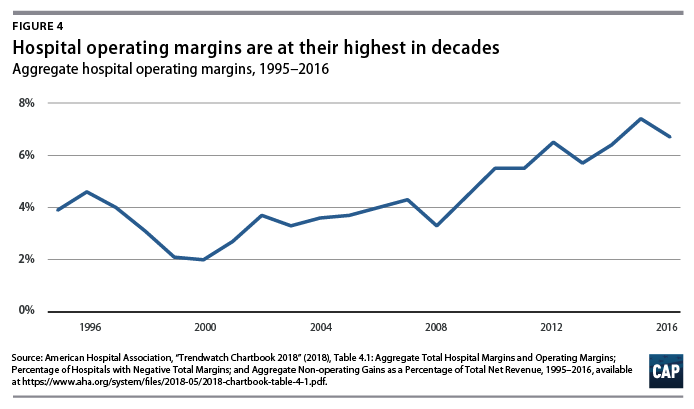

It is no wonder then, that hospital merger and acquisition activity show no signs of stopping.54 The level of activity is, in fact, higher than it was in the early 2000s. In 2017, the hospital industry saw 78 deals involving a total of 216 hospitals.55 The AHA has aggressively defended the trend, including commissioning a report last year claiming that, contrary to the large body of empirical evidence, consolidation does not raise costs.56 Yet, there is no disputing that the hospital industry is increasingly profitable. AHA data show that aggregate operating margins—a measure of the revenues and costs associated with patient care—were 6.7 percent in 2016, and total margins were nearly 8 percent, among the highest levels in two decades.57

Physician-hospital integration is rising

The rise of consolidation in health care provider markets is also happening via vertical integration. In theory, vertical integration between two firms aligns incentives and allows the combined firm to operate more efficiently. In the context of health care, vertical integration between a hospital and physician group may allow for better care coordination and streamlined administration and eliminates the need for the entities to renegotiate contracts. Federal payment policies that reimburse drugs and services at more generous rates in hospital settings have also spawned mergers between hospitals and doctor groups. The introduction of accountable care organizations (ACOs), a reform to the way Medicare pays providers for care, has also been suspected of hastening vertical integration, but performance data do not support the theory that larger provider systems are more successful as ACOs. (see text box for a more detailed discussion of ACOs)

The case of ACOs: Success does not require consolidation

The Affordable Care Act introduced a number of reforms to provider payments, one of which was the creation of accountable care organizations. ACOs are groups of health care providers who voluntarily agree to share responsibility and financial risk for coordinating lower-cost, higher-quality care for a set of patients.58 The ACO programs are designed to incentivize physicians, hospitals, and other providers to coordinate to bring down the total cost of patients’ care while preserving quality. In Medicare’s ACO program, participants who generate savings relative to their benchmarks share those savings with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). At the beginning of the program, many experts worried that ACOs could drive consolidation among providers seeking to minimize their financial risk and maximize their success in the program.59 The FTC and DOJ both scrambled to issue guidance on care integration to adapt to the ACO program’s pressures on providers to align their financial interests.60

Since the 2012 launch of Medicare’s Pioneer ACO program, the number of both Medicare and commercial ACOs has grown steadily. Today, nearly 33 million people—roughly 10 percent of the population—receive care from through an ACO. Of these, 10.5 million are Medicare beneficiaries.61 ACOs appear to be a useful tool for reducing health care expenditures. A study that compared Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) participants with a control group found that ACOs have produced “small but meaningful reductions” in expenditures while providing at least the same quality of care.62 The CMS estimates that MSSP saved the Medicare program an estimated $314 million in 2017.63 Older ACOs have made greater improvements relative to performance benchmarks, suggesting that ACO savings could be on track to grow if experience improves performance.64

While merging entities have often cited ACOs as a justification for consolidation, there is scant evidence that ACOs are behind it.65 First, the ACO program does not appear to be a big contributor to the growing consolidation among physicians and hospitals. A 2017 study by University of Minnesota economist Hannah Nephrash and fellow researchers found an “overall weak relationship” between ACO penetration and consolidation in a market, counter to “the prevailing wisdom that payment reform is driving consolidation of providers as they seek to enter and succeed under new payment models.” The authors suggested that some of the consolidation since the Affordable Care Act could have been defensive, driven by physicians and hospitals joining forces to compete against ACOs.66

Secondly, Medicare ACOs that include hospitals are not more successful. As J. Michael McWilliams, professor at Harvard Medical School, notes: “All else equal, ACOs have stronger incentives to lower spending on care they do not provide than care they do provide.”67 Physician-led ACOs without hospitals may have greater incentives to reduce costs, because there is no conflict of interest in reducing preventable hospitalizations.68 Data from the MSSP bear this out: Physician-only ACOs have saved money on average, and their savings have grown over the duration of the program, while hospital-integrated ACOs did not generate net savings for Medicare in 2015.69

The CMS should do more to encourage greater participation by physician-only ACOs. Among the primary challenges holding back smaller, lower-revenue ACOs is their lack of resources to invest in changes to care delivery and relative inexperience taking on risk-based payment contracts.70 One way to do this is to reduce the risk that smaller ACOs are required to take on relative to that required of larger ACOs. Physician-led ACOs could be given longer time in one-sided risk models, in which the ACOs are rewarded for savings, given that two-sided models, which ACOs can face either gains or losses, have not generated more savings in practice. The CMS could reduce business risk for small ACOs by making performance benchmarks more predictable and calculating them in such a way that does not punish ACOs for their own success. For example, experts have recommended excluding each ACO’s own beneficiaries when calculating regional benchmarks and creating benchmarks that are not rebased according to an ACOs own performance.71

Physicians are increasingly likely to work for a hospital or be financially tied to one. In 1983, about three-quarters of physicians were practice owners compared with less than half, or 47 percent, today, according to the American Medical Association. Roughly one-third of physicians work for hospitals or for practices at least partly owned by a hospital, though the shift toward hospital ownership of physicians has slowed in the last few years.72

It is not clear that the wave of vertical mergers is good for patients. While one study found that integrated systems are more likely to use care management programs for patients with a chronic disease,73 other evidence suggests hospital-physician integration can harm patients. Hospital-physician integration is associated with higher costs and higher prices.74 One study estimated that prices for physician services provided by hospital-acquired doctors increases by 14 percent after an acquisition.75 Physicians in integrated systems are also more likely to refer patients to the owning hospital, which has the net effect of driving patients toward lower-quality, high-cost facilities.76

The Pittsburgh area offers one lesson in the extremes of vertical integration among hospitals, doctors, and insurers. Consumers in Pittsburgh are now limited to two choices for care—Highmark and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center systems—each locking in a mutually exclusive network of hospitals and physicians. A Washington Post article described the city’s market: “Instead of insurer vs. hospital, Pittsburgh split into two distinct health-care silos. Suddenly, people’s choice of health plan became far more integral — determining in which system they would give birth, get flu shots or have surgery.”77

Long Island, New York, is another market that has experienced rapid hospital consolidation. Northwell Health, New York University Langone Health, and other vertically integrated large chains have acquired formerly independent hospitals, leaving a sole independent hospital on the island, which is home to nearly 8 million residents.78

To date, antitrust enforcement agencies have allowed vertical consolidation to occur virtually unchecked for two main reasons. First, the FTC and DOJ’s approach to vertical deals was last formalized in the 1984 Non-Horizontal Merger Guidelines, which generally treated the deals as presumptively pro-competitive and lawful.79 The nonhorizontal guidelines have not been updated despite an accumulating body of evidence that shows vertical integration can facilitate collusion, foreclose new entrants, or raise competitors’ costs.80 Legal scholars Steven C. Salop and Daniel P. Culley have called the guidelines “woefully out of date” and not reflective of “current economic thinking” or “current agency practice.”81

Second, large health systems have been able to acquire smaller practices without attracting scrutiny, because such small transactions typically have not exceeded federal antitrust agencies’ thresholds for increased concentration or change in concentration that trigger an extensive review. As economists Cory Capps, David Dranove, and Christopher Ody observed in their recent work, “antitrust authorities are less likely to investigate a $20 billion firm buying ten $1 billion firms than a similar firm buying a $10 billion firm.”82 Nevertheless, the cumulative effect of numerous small transactions can be highly consequential for the competitiveness of the market.

Vertical merger challenges remain mostly uncharted territory. The FTC won its most prominent case blocking vertical health care integration on horizontal grounds. In 2017, the agency blocked what was essentially a vertical merger between St. Luke’s Health System, a hospital and physician system in Idaho, with another physician practice in the state. However, the FTC’s successful challenge rested on the harms from horizontal consolidation. The court ruled that St. Luke’s could achieve better care coordination with a local physician practice in ways “that do not run afoul of the antitrust laws and do not run such a risk of increased costs.”83

Policies to address consolidation

In the face of increasing consolidation, squeezing greater value out of Americans’ health care dollars requires improvements in three areas. First, antitrust agencies need to step up monitoring and enforcement and should be given the resources to do so. Second, states and the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services can take actions to enhance competition among existing firms. Lastly, because some markets simply lack robust competition, the local nature of health care services demands that policymakers directly address access and affordability problems through price regulation.

Strengthen enforcement by antitrust agencies

Federal and state antitrust authorities are in the best position to slow anti-competitive consolidation, but to be more effective, they need sharper legal tools and greater financial resources.

Subject horizontal mergers to greater scrutiny

Current antitrust strategy heavily relies on showing the short-term effects of mergers on consumer welfare, namely changes in price and output. Courts, as well as state and federal antitrust enforcers, should also give greater consideration to nonprice effects and protect consumers from firms that threaten to use their market power to thwart innovation, entry, and choice. The Federal Trade Commission’s Horizontal Merger Guidelines already spell out that consumers can be harmed in ways unrelated to prices:

For simplicity of exposition, these Guidelines generally discuss the analysis in terms of such price effects. Enhanced market power can also be manifested in non-price terms and conditions that adversely affect customers, including reduced product quality, reduced product variety, reduced service, or diminished innovation. Such non-price effects may coexist with price effects, or can arise in their absence.84

One way that the FTC can boost its enforcement authority without waiting for courts to catch up is by adopting stricter regulations on anti-competitive conduct. Although the FTC has rule-making authority, in the words of current Commissioner Rohit Chopra, it has “largely neglected” rule-making as a tool for monitoring competition and antitrust enforcement.85 Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 grants the FTC the broad authority to challenge “unfair methods of competition in or affecting commerce,” powers that extend beyond the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.86 Rule-making that defines such “unfair methods” could bolster the FTC’s case in instances where potential damage extends beyond what the courts have historically considered, such as erosion of rivals’ bargaining power or harm to consumers because of cross-market acquisitions.87

Antitrust authorities should also consider reviving their use of structural presumptions,88 defining scenarios in which mergers are to be presumed illegal based on their effect on market structure, such as a merger between two rivals that together would control a large share of a market. In such cases, the merging parties would bear the burden of proving the deal is pro-competitive and its benefits are merger-specific. In contrast to an environment in which antitrust authorities are largely responsible for demonstrating anti-competitive effects, greater use of structural presumptions could slow consolidation and help weed out mergers that harm competition.

Boost the FTC’s resources to review mergers, monitor conduct, and challenge anti-competitive behavior

Federal agencies need greater resources to allow for increased monitoring of the state of provider competition and to bring forward strong enforcement cases. As the FTC’s revival of hospital merger challenges demonstrates, investments in research on the potential benefits and harms of future consolidation and to assess the consequences of past deals are vital to enforcement. One area the FTC should examine is the rising concentration in physician markets. As Martin Gaynor, a former FTC official, and his economist colleagues noted, until recently, the lack of data and measures of physician concentration made analysis of those markets difficult.89 Additionally, any holistic analysis of the harms and benefits to consumers of provider consolidation should also consider insurer competition, yet health insurance markets have historically fallen within the purview of the DOJ. Congress should allow the FTC to study insurance markets.90

State antitrust enforcers should take a larger role in monitoring health care competition, especially in cases where mergers are too small to merit FTC review or challenges. Moreover, states know their local markets best. The FTC should establish an ongoing program to backstop states’ efforts by offering technical assistance.

Update standards for vertical merger review

Given the rise in vertical consolidation and the potentially overwhelming market power of the megafirms emerging from it, the FTC should invest more in understanding the consequences of vertical integration in the health care industry, including retrospective analysis of the effects of physician-hospital consolidation on the cost and quality, as well as consumers’ access to care. As part of its review of the evidence, the FTC should consider whether vertical integration dampens innovation, prevents the entry of new firms, and leads already dominant health systems to extend their market power.

The FTC should also issue updated guidelines for vertical merger review across all industries. The parties engaging in vertical deals should bear the burden of proving that the increased efficiency and other beneficial results from the transaction are merger-specific and could not be obtained through other forms of collaboration. While policymakers should allow space for integrated business models to flourish, especially as value-based payment models replace traditional fee-for-service reimbursement in health care, new entrants cannot take root when the market is highly concentrated.

In addition, federal antitrust agencies have existing powers to challenge vertical mergers and bring cases against anti-competitive behavior resulting from vertical integration. The FTC and DOJ should consider making broader use of their authority under the Sherman Antitrust Act to stop conduct such as price fixing and erecting barriers to entry. For example, refusing to deal with competitors or threatening to cut off suppliers or customers who do business with a competitor can be a violation of antitrust rules.91 If a vertically integrated health care system uses its position to discourage physicians from referring patients to outside hospitals, agencies should consider bringing a refusal-to-deal case in such a situation.

Boost competition among providers

Beyond antitrust enforcement, the federal government and state governments can take steps to enhance competition among providers and eliminate policies that inadvertently reward mergers not rooted in providing more efficient, higher-value care.

Require greater transparency for prices, quality, and utilization

One popular theme is transparency initiatives to level the playing field for data analysis and allow consumers to compare prices and quality. Several states have adopted all-payer claims databases, and legislators from both sides of the aisle have voiced support for greater price transparency.92 The CMS has said it will use its authority under the Affordable Care Act to require hospitals to post lists on the internet of their standard charges starting in 2019.93

Studies to date show the effect of transparency on prices is mixed. Some suggest that price transparency leads to lower prices, while another found that all-payer claims databases reduced price dispersion but not the average price.94 Still, other experts worry that price transparency may have the unintended consequence of raising prices among providers who discover they undercharge relative to competitors.95 Quality transparency could nudge patients toward better value care: When consumers have a choice, they gravitate toward higher-quality hospitals.96

There are a few reasons, however, why transparency and comparison shopping have limited potential. First, list prices are largely irrelevant to the consumer at the point of service. The relevant price for insured patients paying for covered services depends on their plan’s cost-sharing arrangements. Even at the payer level, the list prices in a hospital’s chargemaster bear at best only a loose connection to transacted prices.97 Each commercial insurer has its own proprietary, negotiated rates. Medicare and Medicaid set their own prices, and uninsured patients may be billed entirely different amounts. One notable exception is the state of Maryland, which requires hospitals to charge rates that are uniform across payers.98 Second, price transparency, when not accompanied by other payment reforms and decision-making tools, could point consumers in the wrong direction. For example, if lower-priced hospitals tend to provider lower-quality care, price transparency could drive patients toward lower-quality, lower-value services.99

A national all-payer database would enable researchers, insurers, and providers to have access to a large body of information that can be used to improve care and identify areas for improvement. Congress should also amend the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 to allow states to require that self-funded insurance plans’ claims be included in all-payer databases.100

Declare anti-competitive contract clauses illegal

One way that dominant providers maintain hold on their market power is by striking anti-competitive agreements with insurers, which act to keep rates artificially high and prices secret. A recent investigation by The Wall Street Journal found “dozens of contracts with terms that limit how insurers design plans,” including those involving leading health systems.101 Some states have already acted against such practices. Forty-two states require that hospital price or charge data be public, and 18 have banned so-called “most favored nation”(MFN) clauses, in which a provider guarantees no other insurer will get a lower rate.102 States should take further action to ban gag rules and nondisclosure agreements in provider contracts, which prohibit the sharing of pricing information.

Many other anti-competitive state laws remain on the books, however. Nine states have “any willing provider” clauses for health care providers, which prevent health insurance plans from excluding providers from their networks.103 In addition to repealing such statutes, states can also foster competition via insurance networks by repealing anti-tiering and anti-steering clauses, which hamper plan designs that direct patients toward higher-value providers. At the federal level, the CMS should ban providers who engage in MFN, anti-steering, and anti-tiering clauses in provider contracts, from participation in Medicare.

Make provider payments site-neutral

Medicare has historically reimbursed services performed in a hospital at a higher rate than those administered in a physician’s office. For services where comparable care can be provided in either setting, this payment differential rewards health systems for shifting services into the hospital environment, ultimately driving up costs and wasting resources.104 Closing the payment gap would eliminate the incentive for hospital systems to gobble up physician practices in order to bill for services under the hospital outpatient payment schedule. It would also enhance competition between hospitals and other providers of outpatient care.

The CMS is moving toward site neutrality. In 2016, the agency equalized Medicare payments for services occurring at off-campus hospital outpatient department and physician’s offices.105 This past summer, CMS proposed site neutrality for payments to ambulatory care centers and hospital outpatient services, a move that is expected to save Medicare and its beneficiaries $760 million in 2019.106 The CMS further should modify Medicare payments to curb higher reimbursements to hospitals for services that can be performed at least as safely and effectively in a physician’s office, including those performed by on-campus hospital outpatient departments.107

The CMS should also reform the federal drug discount program known as 340B, which enables providers, including hospitals, that serve low-income populations to purchase outpatient drugs at a discount. Although the original mission of the program was to improve low-income patients’ access to care, one side effect of the program has been hospital-physician consolidation.108 The 340B discount for hospital outpatient care is available to physicians who are part of a hospital system but generally not granted to those who are not. One study found that 340B-eligible hospitals were more likely to employ or acquire physicians practicing hematology and oncology in order to capture potential savings from that drug-intensive specialty.109 The 340B program should be reformed to minimize its anti-competitive effects—for example, by narrowing the discount eligibility to low-income patients rather than to broad groups of providers or by requiring participating hospitals to document all the benefits they provide as part of the safety net to the underserved community rather than reporting just the volume of uncompensated care and charity care.110

Repeal laws that unnecessarily restrict the supply of health care providers

The scope of practice refers to the legal restrictions on services that health care professionals—including nurse practitioners, certified nurse midwifes, and physician assistants—are allowed to provide to patients given their professional license.111 For example, scope-of-practice laws can prohibit nurse practitioners from performing services they are trained to deliver or require that certain duties be performed only under direct supervision by a physician. While limits can be justified where they protect patient health and safety, overreaching scope-of-practice laws serve to limit competition and can harm access to care. A 2014 FTC report concluded that laws requiring physician supervision “exacerbate provider shortages and thereby contribute to access problems” while also increasing the cost of care.112

A recent Brookings Institution report reviewed the academic literature on the topic and found no evidence of harm to patients associated with less restrictive scope-of-practice laws and concluded that such laws mostly serve as a barrier to entry for health care providers.113 Economists Jeffrey Traczynski and Victoria Udalova have estimated that eliminating scope-of-practice restrictions on nurse practitioners would generate $543 million in savings from reduced use of emergency department care for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions.114

Scope-of-practice restrictions should be lifted in areas where evidence shows other professionals can safely provide comparable quality of care. States should eliminate unwarranted limits on scope of practice in order to improve patients’ access to care. Federal health programs can also play role in enabling care providers to practice to the top of their license. In a 2010 report, the National Academy of Medicine, called for expanding Medicare coverage for services from advanced practice registered nurses, among other reforms, to allow nurses to “practice to the full extent of their education and training.”115 More recently, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission recommended that the CMS give rural hospitals greater discretion to allow nurses to perform outpatient procedures without direct physician supervision in order to alleviate care shortages.116

A second major category of restrictions on provider competition that states should repeal is certificate-of-need (CON) requirements. CON laws, which require hospitals or other inpatient care facilities to obtain permission from state agencies in order to enter a market or build a new facility, are a relic of state attempts to control health costs in the 1970s by limiting hospitals’ capacity. The argument behind CON laws was that hospitals raise prices for care to cover their fixed costs when they have excess capacity.

While more than half of states still have active CON laws, such requirements are arguably outdated.117 Fee-for-service payment systems historically rewarded hospitals for providing larger volumes of care, but current provider reimbursement arrangements are less likely to encourage excess capacity. The research on the effectiveness of CON laws is mixed. Some studies suggest the laws yield greater cost-efficiency and generate higher patient volumes in hospitals, in turn providing doctors with more practice and expertise. A number of recent empirical studies have found mixed evidence at best on any connection between CON laws and health outcomes, and one did not detect any link with all-cause mortality.118 States with CON laws are also less like to see entry by new hospitals and nonhospital providers.119

Bring down health care prices in already concentrated markets

In areas of the country lacking sufficient competition, market-based solutions for controlling prices break down. Some places are dominated by a single major health system, while other markets are too small or sparsely populated to support competing hospitals or specialty providers, or to attract any at all. In such markets, “Empowering consumer choice is of little benefit where choice is lacking.”120 Bringing down health care costs and ensuring access to care requires policies to address extant market power.

Establish a patient ombudsman for health care cost and access

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should house an ombudsman to serve all Americans on issues of health care costs and access. Such public advocates already exist for other issues on the state and federal level, including the IRS’ taxpayer advocate.121 While the CMS has an ombudsman serving Medicare beneficiaries, this new office would create a centralized point of contact for health consumers to file complaints and requests.122 The ombudsman would also advocate for patients and taxpayers by assessing regulations for their impact on the cost and quality of health care. Coupled with increased efforts by HHS to monitor provider competition and rates, the office could halt and deter anti-competitive conduct by insurers and providers by uncovering instances where patients and competitors were treated poorly or unfairly.

Cap the prices that providers can charge

Capping rates would limit the rents that provider systems with market power can extract from consumers and protect patients from exorbitant medical bills. Congress should ban providers from engaging in balance billing, the practice of charging a patient for the difference between what the patient’s insurance pays the provider and the charged amount. Patients can often be hit with unexpected bills such as that from an out-of-network anesthesiologist providing care at an in-network hospital. About one-third of privately insured Americans report receiving “surprise bills” from medical providers, including bills from out-of-network providers.123 In numerous extreme cases, hospitals have sent consumers six-figure medical bills.124 The outrageous prices are eliciting bans on balance billing. As of 2017, California law prohibits in-network facilities from sending out-of-network bills to consumers.125 U.S. senators from both sides of the aisle have drafted national measures to limit out-of-network charges. Sens. Maggie Hassan (D-NH) and Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) proposed limiting out-of-network charges to levels close to Medicare and negotiated in-network rates.126 A separate bipartisan bill sponsored by Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-LA) would limit patients’ liability to the average in-network rate among private plans.127

Another more direct way to lower prices for consumers is to set limits as a percentage of Medicare rates. Medicare Advantage already requires that all out-of-network providers accept at least Medicare fee-for-service rates,128 essentially capping rates. A recent working paper from the Congressional Budget Office suggests the rule not only results in less variation in rates but also lowers both the in-network and out-of-network rates that commercial insurers pay in Medicare Advantage.129 Congress could extend a Medicare rate-based cap to all services from providers who participate in Medicare, regardless of the payer.

Equalize prices among payers and across providers

In a bolder approach to regulating rates, the government could set payer rates to level prices among payers. Setting all-payer rates across providers would ensure fair prices for consumers while still allowing providers to compete for business from patients and insurers along other dimensions such as overall cost, clinical outcomes, and patient experience. Regulators could adjust rates or create supplemental payments as needed to guarantee that Americans in underserved communities have adequate access to care services.

In addition to leveling rates among payers and bringing down prices, an all-payer rate gives the government another tool to control the growth rate of health spending. Some states already operate rate-setting or rate-monitoring programs.130 Maryland has operated a decadeslong program of all-payer rate setting for hospitals and is now adding an additional level of cost control through global budgeting.131 Although Massachusetts’s original hospital rate-setting program was eclipsed by the rise of managed care in the 1980s and shuttered in 1991, since 2012 the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission has monitored price growth and made recommendations on payment reform.132 Moreover, rate-setting authority is central to many countries’ universal health insurance programs, as well as the Medicare for All-type proposals for the United States, including those put forth by Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-VT) and the Center for American Progress.133

Conclusion

Given that health is central to Americans’ well-being and that taxpayers have a large stake in the health care system, it is time to re-examine the role that concentration among providers plays in the cost of care. Despite the fact that a small handful of firms control already most of the market in many areas of the health care sector, merger activity hit an all-time high in 2018.134

It is time to stop presuming that consolidation in health care will be innovative and pro-competitive. Deals that are good for business are not necessarily in consumers’ best interest. The loss of independent hospitals represents a loss of choice for patients, and lower costs for health systems do not translate into lower prices for patients. As economist Martin Gaynor recently pointed out in a congressional hearing, “Since consolidation in health care has been occurring for a long time, it seems unlikely that the promised gains from consolidation will now materialize if they haven’t yet.”135 Antitrust authorities, whose efforts to protect competition in recent years have been stymied by inadequate resources for pursing merger challenges and monitoring conduct, should subject mergers to greater scrutiny and should be given the resources to keep abreast of the developments in health care markets. The current state of health care provider markets demands stronger enforcement by federal and state antitrust authorities, policies to support more robust competition among providers, and limits on prices in already concentrated markets. Any efforts to control health care costs and improve care for patients should consider the growing role of market power.

About the authors

Emily Gee is the health economist of Health Policy at the Center for American Progress.

Ethan Gurwitz is a law student at Harvard Law School and was formerly a policy analyst for Economic Policy at the Center.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible in part by a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The statements and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the Center for American Progress.

Aditya Krishnaswamy, Nikki Prattipati, and Rhonda Rogombe provided research assistance.