Child care in the United States is both unaffordable and hard to find.1 Seventy-one percent of parents report that locating quality, affordable child care in their communities is a serious problem.2 Moreover, a recent survey found that the cost of child care is the top reason that adults in the United States are having fewer children.3 It is little wonder that the movement for child care reform is growing.

Exhaustive research clearly demonstrates that early childhood—birth through age 5— is a pivotal period for child development, with about 90 percent of brain growth occurring before a child’s fifth birthday.4 Therefore, it is crucial that children spend time in safe and enriching care environments. Voters certainly agree that government has a role to play in helping young children to succeed, with 3 in 4 voters saying they support Congress increasing investment in child care and early education.5

The call for action on child care has gained traction over the past year, including with the introduction of the most comprehensive child care legislation to date.6 In September 2017, Sen. Patty Murray (D- WA) and Rep. Bobby Scott (D-VA) put forward the Child Care for Working Families Act (CCWFA). If enacted, this bold, holistic child care bill would ensure that no low- or middle-income family spends more than 7 percent of their income on child care. In addition, the bill would guarantee a living wage for early childhood educators, as well as invest in increasing the number of quality child care programs available in communities and making other critical child care quality improvements. The bill would also provide incentives and support states to expand preschool to 3- and 4-year-olds. Since being introduced, the bill has continued to garner support, and at the time of this brief’s publication, 32 senators and 126 representatives had signed onto the bill as co-sponsors.7

See also

Congress included the largest-ever funding increase for the nation’s child care assistance program—the Child Care and Development Block Grant—in the fiscal year 2018–2019 budget, which serves as a down payment on the CCWFA.8 While this funding increase represents a critical first step that will lead to real improvements for families, a more comprehensive solution is needed to help all families afford and access quality child care.

As parents continue to struggle—and political leaders on both sides of the aisle highlight child care as a pressing issue9—the CCWFA remains a viable and much-needed solution to address the nation’s child care crisis. This issue brief highlights how families and workers in every state would benefit in a single year under the CCWFA:

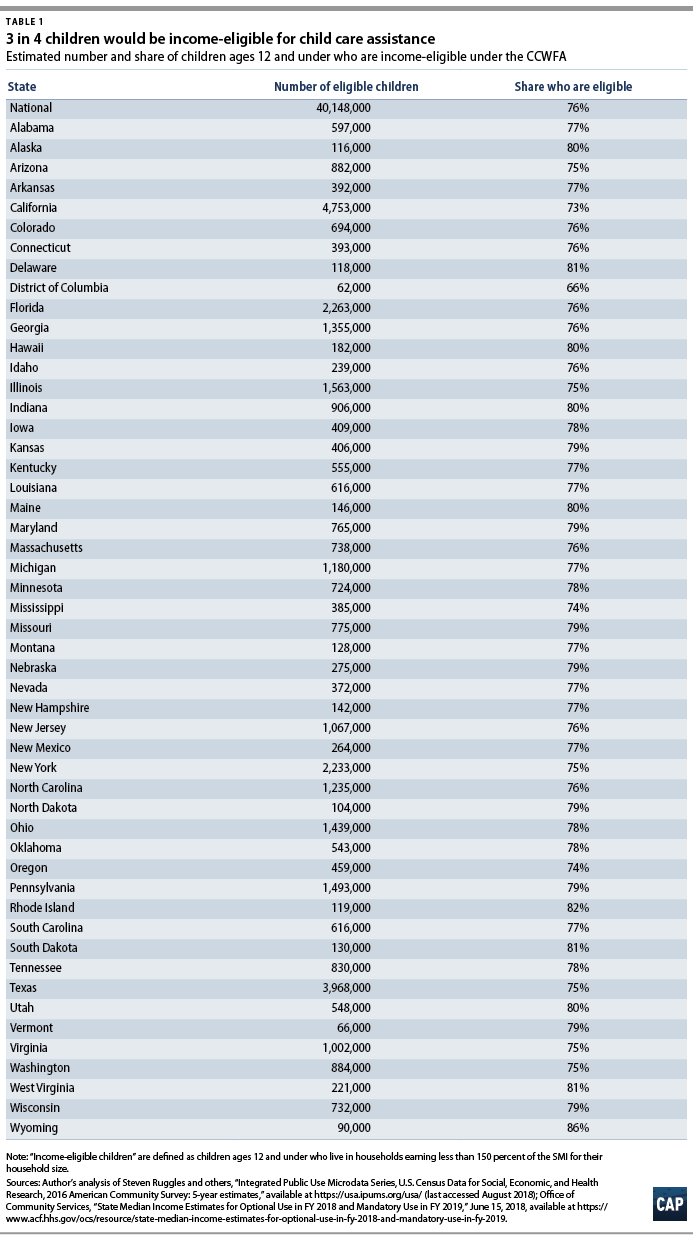

- Three in 4 children ages 12 and under would be income-eligible for child care assistance.

- The median family’s child care payment would not exceed $45 per week.

- All child care workers would earn a living wage. Three-quarters of child care workers currently earn below a living wage and would therefore see a pay increase.

Snapshot: How the CCWFA would work

A typical married couple, let’s call them James and Michelle, live with their 1-year-old daughter and 4-year-old son in Grand Rapids, Michigan. James works as a mechanic and Michelle as a home health aide, bringing home a combined income of about $81,000 each year. About a quarter of their income currently goes toward paying for child care for their two children, and after paying for their mortgage, car payment, health insurance, and groceries, James and Michelle barely make ends meet each month. Michelle has considered leaving her job to stay home with her children instead of spending half of her salary on child care but worries about losing her income and falling behind in her career.

Under the CCWFA, James and Michelle’s child care payment for two children would be capped at $32 each week. They would save nearly $16,000 per year on child care—enough to pay for two years’ worth of groceries for their family.10 (see calculations in Appendix)

About the CCWFA

The CCWFA, if passed, would help families with children ages 12 and under afford high-quality, flexible child care, as well as after-school and summer care. Under the CCWFA, families earning up to 150 percent of their respective state median income (SMI) would be eligible for assistance and would spend no more than 7 percent of their income on child care, no matter how many children they have. As proposed, the bill operates on a sliding scale, meaning that lower-earning families would pay a smaller percentage of their income toward child care. (see Appendix table) For example, an Ohio family of four earning $81,400—the median income for the state—would be expected to pay a maximum of $1,600 per year for child care. An Ohio family earning about $61,000 or less per year would have no copay obligation; in other words, they would pay nothing for their child care.

Importantly, the CCWFA would holistically address quality, cost, supply, and wages in the nation’s child care system instead of relying on piecemeal efforts. Specifically, if enacted, the CCWFA would:

- Guarantee child care assistance to low-income and middle-class families earning up to 150 percent of the SMI.

- Cap child care payments at 7 percent of a family’s income to align with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ definition of affordable child care.11

- Ensure that early childhood educators earn a living wage and are compensated at the same level as elementary school teachers if they have the same credentials and experience.

- Invest in improving quality in child care programs and increasing the number of child care slots in child care deserts, or areas with an undersupply of child care.12

- Provide funding and incentives for states to expand high-quality preschool programs to serve 3- and 4-year-olds.

The CCWFA would have tangible benefits for family economic security, American businesses, and the nation’s economy. Specifically, the CCWFA would create an estimated 2.3 million jobs by enabling 1.6 million parents to join the labor force as a direct result of access to child care subsidies and by creating an estimated 700,000 new jobs in the field of early childhood care and education.13 Nearly 80 percent of increased employment would be among low-income mothers, which would lift at least 1 million families out of poverty.14

The CCWFA would create an estimated 2.3 million jobs.

More children and families would be eligible for child care assistance

Under the CCWFA, all eligible families would receive child care assistance. The Center for American Progress’ analysis finds that under the bill, 3 in 4 children—about 40 million—ages 12 and under would be income-eligible for child care assistance.15 (see Table 1) Eligible families would be able to use their child care subsidy to pay for child care during traditional work hours, as well as during evenings, on weekends, and in the summer. Expanding access to child care assistance will help to promote parental workforce participation and will ensure that children spend time in safe and enriching environments while their parents are at work.16

Currently, just 1 in 6 eligible families receives a child care subsidy.17 Research shows that receiving a child care subsidy is associated with increased maternal employment and educational attainment.18 Moreover, attending a high-quality early learning program can have extensive benefits for young children’s development.19

Parents would pay less and have greater access to high-quality child care

Under the CCWFA, the median family of four in every state would spend no more than $45 each week on child care, no matter how many children they have. (see Table 2) Maximum payment rates for the median family of four would range from $23 per week in Mississippi to $43 per week in Massachusetts.

Under the CCWFA, the median family of four in every state would spend no more than $45 each week on child care, no matter how many children they have.

While safe and reliable child care is a necessity for working parents, it is often economically out of reach. For many families, child care is the single largest household expense. Nationally, the average annual cost of center-based child care is around $20,000 for a family with an infant and a preschooler.20 Under the CCWFA, young families stand to save thousands of dollars each year, freeing up a significant amount of money to pay for other necessities. For example, the typical family of four in Minnesota would save enough on child care in one year to pay for three years’ worth of groceries—about $25,000.21 A median family of four in Nevada would pay just $28 per week on child care, saving roughly $17,600—enough to pay their electric bill for 13 years.22

Beyond making child care more affordable for millions of families, the CCWFA would enable families to access high-quality child care programs that they may not otherwise be able to afford. While quality early childhood education is meant to help level the playing field for disadvantaged children, the reality is that a child’s participation in a quality early learning program often depends on whether their parents can afford to pay for one. The CCWFA would calibrate child care subsidies to cover the true cost of providing quality child care, so that all families can afford a quality program.23 The bill would raise subsidies to levels that would enable child care providers to offer higher wages for early educators, improve physical classroom spaces, and support professional development opportunities for educators—several important elements of quality child care.24

The CCWFA would promote a more equitable child care system and give parents greater freedom to select a child care program based on factors other than cost—such as quality, curriculum, location, or operating hours. At the same time, the bill invests in building the supply of quality child care programs by incentivizing quality improvements. Ultimately, the CCWFA will give all parents the ability to choose from a broader set of high-quality child care options, no matter their income.

At least 3 in 4 child care workers would receive a raise

Paying a living wage—or enough to meet their basic needs in a given state—to all early childhood educators is a key pillar of the CCWFA. Most child care workers would receive a raise under this bill: Nationally, 3 in 4 full-time child care workers currently earn below the estimated living wage in their state and would therefore see a pay increase to earn at least a living wage.25 Furthermore, the CCWFA would raise earnings by an estimated 26 percent for child care workers and create an estimated 700,000 new jobs in the early childhood sector.26

Currently, the early childhood workforce comprises approximately 2 million educators, most of whom are women, and about 40 percent of whom are people of color.27 Despite early educators being critical to promoting healthy child development and to supporting families, they are grossly underpaid. The median wage for a child care worker is $10.72 per hour, or slightly more than $22,000 annually, putting them in the bottom 2 percent of earners in the nation.28 Earning poverty-level wages places significant strain on educators, threatening their well-being, which can make it more difficult for them to provide optimal care to children.29 In fact, higher levels of economic stress among early educators has been linked to lower classroom quality.30

The care and education of young children requires knowledge, experience, patience, and energy. Offering more competitive wages gives greater recognition to the level of skill necessary to be an effective early educator, which in turn will help to attract and retain high-quality educators who may otherwise leave for higher pay teaching preschool or elementary school.31 Retaining qualified and experienced early educators will ultimately enhance the quality of service that children in child care receive.

Conclusion

The reality is, America’s child care system is not going to fix itself. Each day that Congress waits to pass comprehensive child care reform embodied in the CCWFA, American families will continue to struggle to pay for child care; early educators won’t earn enough to make ends meet; and businesses will continue to lose productive employees.

The recent investment in the Child Care and Development Block Grant was a critical first step toward addressing this problem; now, the momentum toward a more comprehensive solution must be sustained. The CCWFA is smart policy that is well worth the federal investment. American children, families, workers, and the economy cannot afford to wait another year to enact this innovative and necessary legislation.

Appendix

Under the Child Care for Working Families Act, a family’s payment rate for child care is based on a sliding scale. The specific breakdown is as follows:

- Tier 1: Families earning less than or equal to 75 percent of the SMI will not pay a copayment.

- Tier 2: Families earning between 75 percent and 100 percent of the SMI will pay at least a nominal fee and a maximum of 2 percent of their income.

- Tier 3: Families earning between 100 percent and 125 percent of the SMI will pay between 2 percent and 4 percent of their income.

- Tier 4: Families earning between 125 percent and 150 percent of the SMI will pay between 4 percent and 7 percent of their income.

To view the Appendix table, download the PDF.

Leila Schochet is the research and advocacy manager for Early Childhood Policy at the Center for American Progress.