See also: The Changing Role of the Principal: How High-Achieving Districts Are Recalibrating School Leadership by Lee Alvoid and Watt Lesley Black Jr.

Buried in the debate over teacher evaluation is a nagging concern about principals. The burden of carrying out teacher-evaluation activities falls squarely on the shoulders of these school administrators. They have to observe teachers—often multiple times per school year—and complete a rubric about the instruction; they also need to complete a post-observation conversation with each teacher. These activities, while essential to improve education, are a radical shift in principals’ responsibilities, which have historically focused on administrative tasks rather than instructional support.

Principals are feeling the change in their scope of work. In a recent national survey, 69 percent of principals said their responsibilities had changed in the past five years, and 75 percent said their job had become too complex.

We reviewed studies from a number of states that collected data on the pilot implementation of new teacher-evaluation systems to see how principals responded to their increased responsibilities. Specifically, we reviewed implementation studies from Michigan, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Chicago, as well as a report that surveyed districts in Maryland, New York, and North Carolina. These districts received federal grants through the Race to the Top initiative. Our review confirmed that principals are struggling with their new responsibilities.

Consider the following examples:

- In Michigan, the median principal reported spending 248 hours—or 31 full work days—on teacher-evaluation activities, and 47 percent of principals said they spent a lot of time on evaluation.

- In Connecticut, surveys of principals involved in the pilot implementation found that the average principal was responsible for evaluating 25 teachers per school year. In interviews with researchers, Connecticut principals reported struggling to complete the required number of observations—often completing only two formal and two informal evaluations, even though three of each are required.

- Two-thirds of states that received Race to the Top grants—which required the implementation of teacher-evaluation systems—reported that managing principal workloads was a critical challenge. A report from the Government Accountability Office on evaluation implementation during the 2012-13 school year noted that administrators in a New York state district said that the time it took to observe teachers prevented them from providing meaningful post-observation feedback.

- In New Jersey, 89 percent of principals said that they spent more time on teacher observations when piloting the new evaluation system. They reported an average time of three hours to complete all aspects of an evaluation.

- Chicago principals reported that it took an average of six hours to complete an evaluation. They also said that because of the time demands, they sometimes had to choose between completing teacher evaluations and performing other duties, such as meeting with parents or students.

Despite these issues, states and districts have yet to fully address principals’ needs through strong professional-development activities. According to our analysis of the latest data from the Schools and Staffing Survey, or SASS, 95 percent of principals believe they have a major influence on teacher evaluation. But principal professional-development activities fall into the same kinds of weak training forms that have been widely criticized in research on teacher professional development.

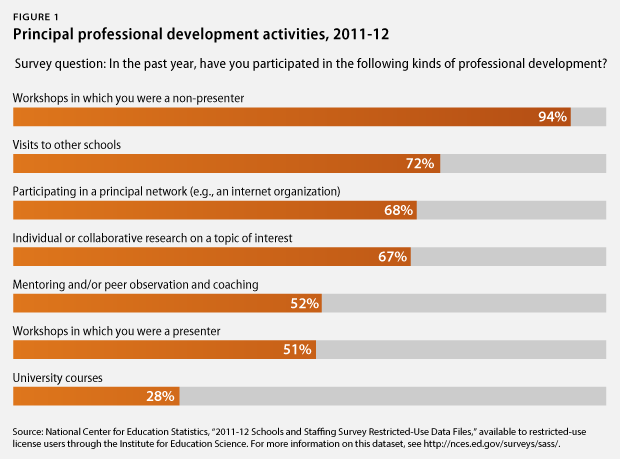

According to SASS data from the 2011-12 school year, most principals participated in workshops as an attendee, which is one of the least effective forms of support, according to professional-development research. Among the activities that can effectively improve performance are job-embedded mentoring and coaching. As is seen in the figure above, only a little more than half of principals—52 percent—reported participating in this type of professional development.

These data indicating that principals are overwhelmed with new evaluation responsibilities, coupled with the weak professional-development activities they participate in, call for an overhaul of support systems for school administrators. States and districts need to design and implement better programs and structures to ensure that principals have the training and support they need to effectively carry out teacher evaluation.

In a new report from the Center for American Progress, “The Changing Role of the Principal: How High-Achieving Districts Are Recalibrating School Leadership,” authors Lee Alvoid and Watt Lesley Black Jr. make sensible recommendations for principal professional development, such as focusing on helping them coach teachers and improving districtwide teaching and leadership frameworks. The report’s recommendations are directed at district leadership, which makes many of the decisions related to principal professional development. They include:

- Redesigning school organizational charts and job descriptions

- Developing instructional leadership capacity around the principal

- Focusing principal training on coaching teachers

- Building the capacity of central office administrators to support principals

- Providing regular opportunities for principals to gather around self-selected problems of practice

- Developing partnerships with universities and nonprofits to recruit and train future principals

- Developing and training principals on districtwide teaching and leadership frameworks

- Providing technological supports that allow administrators to record and share instructional data

As the teaching profession changes, so too will the principalship. Instead of piling on more work for school leaders, it would be wise to address the shifts in the role of the principal so that he or she can focus on the activities that have the most impact on student learning.

Jenny DeMonte is the Associate Director for Education Research at the Center for American Progress. Kaitlin Pennington is a Policy Analyst on the Education Policy team at the Center.