In December 2017, Congress quietly included a provision to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for oil drilling in the tax bill signed by President Donald Trump. In the months since, the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) has been in a headlong rush to sell the country’s largest wildlife refuge to the oil and gas industry. After holding just a 60-day public comment period, the DOI has promised to expedite its environmental review of drilling in the refuge—aiming to complete it in just one year, rather than the average three-year timeline,1 and to hold a lease sale by 2019.2

Though the sellout of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is designed to benefit the oil industry, most of the largest oil companies in the United States have been largely silent about their intention to bid on leases and pursue exploration projects in the refuge. This public silence is likely motivated by companies’ recognition that drilling the Arctic Refuge would be highly controversial—and could cause reputational and brand damage. In fact, a group of investors representing trillions of dollars in assets recently penned a letter3 urging banks and oil and gas companies not to initiate development in the refuge.

One of the largest private companies in the United States, on the other hand, has been abundantly clear about its support for drilling the Arctic Refuge and has spent millions of dollars over the past two decades to convince Congress to overturn a prohibition on drilling on the refuge’s coastal plain. The Arctic Slope Regional Corp. (ASRC), an Alaska Native regional corporation with an annual revenue of $2.5 billion, has already submitted an application to do a seismic survey of the coastal plain, the area of the refuge that would be leased and drilled.

Rather than proposing a small footprint for such a sensitive area, the application—which was filed jointly by the ASRC, Kaktovik Inupiat Corp., and SAExploration Holdings Inc.4—would cover the entire coastal plain and calls for two work camps of up to 160 people each, as well as airstrips, seismic machinery, and operations that would occur 24 hours a day, seven days a week.5 This extensive seismic work would put the region’s polar bears and sensitive tundra environment at risk before drilling even takes place. The DOI’s Bureau of Land Management is currently accepting comments on whether an environmental analysis is even necessary to approve the seismic application.6

The ASRC has lobbied for decades to open the refuge to drilling—in part, because it controls some of the subsurface rights in the coastal plain and therefore stands to benefit financially if oil is found there.7 Yet, this multibillion-dollar oil and gas corporation is largely unknown outside Alaska. Amid the current development threat to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, it is worth examining what the ASRC is; why it is such a powerful political force; and what it has to gain financially from the sellout of America’s last great wilderness.

What are the ANCSA and the ASRC?

In 1971, just as oil discoveries began, Congress passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act8 (ANCSA) to settle more than 100 years of disputes regarding various land claims by Alaska Natives—and in doing so, generated additional economic opportunity in the 49th state. The largest land claims settlement in U.S. history, ANCSA established 12 Alaska Native regional corporations—a 13th was later added—that received title to claims on more than 40 million acres of land in Alaska.9 These Alaska Native regional corporations are distinctly different from Alaska Native tribes. A regional corporation includes all the Alaska Natives who live in a given region, delineated by ANCSA, and who chose to enroll individually in a corporation at its outset—meaning each regional corporation can encompass members from a number of different tribes. These Alaska Native regional corporations each act as a state-chartered, for-profit, economic entity.10 The ASRC specifically was incorporated11 on June 22, 1972, and is today one of the largest private landowners12 in Alaska with nearly 5 million acres13 of land on Alaska’s North Slope, much of which has a high potential for development.

In addition to dividing land claims by corporation, ANCSA also mandated that Alaska Natives and their descendants born before 1971 each receive14 100 shares in their respective regional corporation. These shares cannot be sold or traded but can be passed down to family members born after 1971 and generate annual dividends. Each year, about 40 percent15 of the ASRC’s annual earnings are distributed as dividends to its shareholders, with the remaining 60 percent reinvested in the company for long-term growth purposes. Also stipulated16 in ANCSA is the requirement that 70 percent of all revenues from natural resource development be shared among all of the Alaska Native corporations—a requirement known as the 7(i) provision.

In 1989, the ASRC was one of only four Alaska Native regional corporations to broaden its base by opening17 up enrollment to Alaska Natives born after 1971. This model means that over time, the ASRC has grown18 into a private, for-profit corporation with 12,000 employees and 13,000 Inupiat Eskimo shareholders across Alaska and the United States.

The ASRC is a large corporation focused on opening the refuge to drilling

The amount of the ASRC’s annual revenues—primarily from activities related to resource extraction and sales19—makes the corporation the 196th-largest private company20 in the United States. Between 1978 and 2016, the ASRC paid out $915 million21 to its 13,000 shareholders and in November 2017 became the first Alaska Native corporation to distribute more than $1 billion.22 In 2015, the ASRC reported an annual revenue of $2.5 billion.23 It has at least nine main24 subsidiary companies across six areas25 of work, all of which have further acquired other subsidiaries, creating a vast network of nearly 60 companies across the country.

Today, the ASRC owns the subsurface rights to more than 92,000 acres26 of land within the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge—the area where development would occur—thanks to a controversial 1983 land deal between the DOI and the ASRC known as the Chandler Lake exchange.27 The deal allowed the ASRC to gain subsurface rights to land within the coastal plain in exchange for giving up acres of equivalent value in Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve to the DOI, which had an interest in owning all of the contiguous land acreage within the park boundary so as to manage it cohesively.28 This land deal effectively gave the ASRC a leg up over other Alaska Native corporations; after the Chandler Lake exchange, the ASRC was granted potentially oil-rich land to which other Alaska Native corporations did not and still do not have access.29 Although regulators approved the land swap at the time, the U.S. Government Accountability Office reviewed it in 1989 at the request of Congress and found the exchange not to be in the government’s best interest.30

Despite the ASRC’s subsurface ownership, federal law prohibited any drilling until the entire coastal plain is opened. But in 1984, the ASRC signed an agreement leasing31 all of those acres to Chevron Corp. and BP. Chevron is responsible for drilling the only test well32 in the refuge; yet, information about its contents have been kept secret,33 pursuant to a confidential agreement34 among Chevron, BP, the Alaska Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, a select few at the Alaska Department of Natural Resources, the Kaktovik Inupiat Corp., and the ASRC.

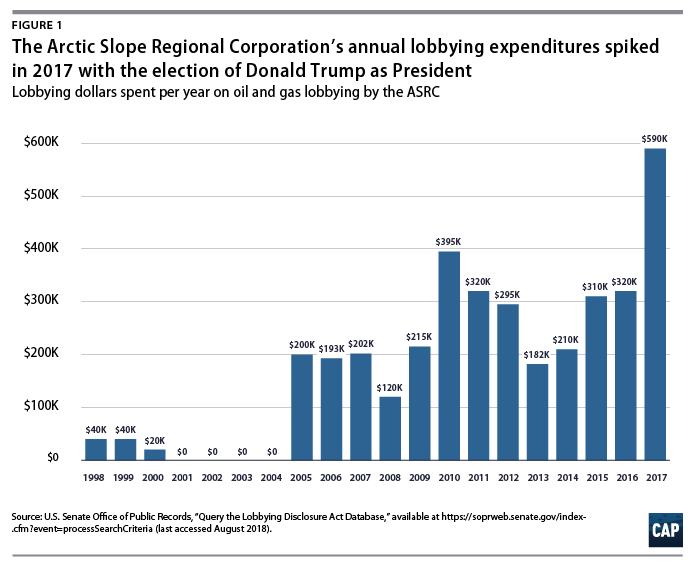

The ASRC’s ownership of subsurface rights in the coastal plain has made the corporation one of the most vocal proponents35 and consistent lobbyists for opening the Arctic Refuge to oil and gas drilling over the last 30 years. Its lobbying investments spiked36 after Donald Trump assumed the presidency in 2017; with a Republican Congress and president, drilling proponents once again saw an opportunity to open the refuge to drilling.

In fact, the ASRC’s lobbying expenditure37 in 2017 was the highest that it has ever been, nearly doubling its next-highest year in 2010—which is also when Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), a strong proponent of refuge drilling, won an unlikely write-in election38 with support from the ASRC-funded group Alaskans Standing Together.39 All $590,000 that the ASRC spent on lobbying in 2017 went to pushing for oil and gas development. Even in 2018, after Congress opened the Arctic Refuge, the ASRC remains in the country’s top 5040 oil lobbying groups by spending.

The ASRC’s efforts to further expand its financial returns from additional oil and gas extraction are well-known in Alaska. In a 2017 story41 for InsideClimate News, a resident of Kaktovik, an Inupiat village at the very northern tip42 of the coastal plain in the refuge, was quoted as saying, “[The ASRC and other corporations] go to D.C. as if they’re representing the native people of the North Slope. … But they’re representing the interests of a for-profit corporation that’s in joint venture with Chevron and BP.”

The ASRC’s financial interests vs. other Alaska Natives’ human rights

The ANSCA’s requirement that a portion of oil and gas revenues be shared among Alaska Native corporations has raised the question about whether the ASRC’s potential revenues from drilling the Arctic Refuge should likewise be shared. Some Alaska Native corporations have pushed repeatedly for legislation43 that would require the ASRC to share its refuge revenues among these corporations, emphasizing that the ASRC was never originally intended to have title to lands beneath a potentially oil-rich wildlife refuge and only achieved this special right through a controversial land swap.

The ASRC has pushed back firmly on these efforts. Last year, ASRC President and CEO Rex Rock wrote44 in a letter to the Bering Straits Native Corp. that the “ASRC and its shareholders strongly oppose this proposed taking” of their private property. Rock further wrote that the ASRC believes that its leased lands are actually exempt from the 7(i) provision of ANCSA—which requires that oil and gas revenue be shared—thanks to the 1983 Chandler Lake exchange.45 Three weeks after it sent the initial letter, the ASRC pulled out of the Inuit Arctic Business Alliance, a group formed by the ASRC and other Alaska Native corporations to ensure that each benefited from Arctic development. This means that the ASRC may not have to share any revenues from their 92,000 leased acres as they are developed. What’s more, the House just passed an Interior and Environment Appropriations bill with a provision that would require 3 percent of the state of Alaska’s share of revenue for Arctic Refuge oil and gas drilling to be given to Alaska Native corporations, essentially allowing the ASRC to profit twice from any drilling in the refuge.46

Though the ASRC is hopeful that it will profit financially from oil and gas drilling in the Arctic Refuge, many Alaska Natives fear that exploitation of the coastal plain will result in the loss of sacred lands, subsistence resources, and potential health impacts.47 For instance, many members of the eight villages across Alaska’s North Slope—and Kaktovik, in particular,48 situated within the Arctic Refuge—rely on subsistence hunting for part or all of their diet. Being so far north, foods shipped to and sold in stores in the area are exorbitantly priced: A pound of meat, for example, costs49 $27. The refuge is home to much of the wildlife that these populations hunt and eat, meaning that oil and gas development that disturbs50 that wildlife is a direct danger to their food security and livelihood as well. Health impacts from poor air quality thought to be caused by proximal oil and gas drilling such as in the town of Nuiqsut, have also raised additional worries about oil and gas drilling on the North Slope.51 Such concerns cause further friction between proponents of drilling, such as the leadership of the ASRC, and other Alaska Natives.

The Gwich’in people have inhabited the Arctic Refuge region of Alaska for generations and rely on52 the health of its land and wildlife for food, clothing, and cultural survival. The Porcupine caribou herd, which calve on the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge,53 is not only a food staple but are also sacred to the Gwich’in, whose way of life would be irreparably changed if oil and gas interests bring exploration and drilling in the area.54 In particular, the impacts of an oil and gas spill55 in this pristine region would be devastating.

The ASRC’s outsized influence in Trump’s DOI

The ASRC secured a major legislative victory last year in the passage of a congressional rider authorizing drilling in the Arctic Refuge. Now, the corporation is looking to President Trump’s DOI to rapidly proceed with oil lease sales before the rider is repealed or until a new administration can seek to block drilling.

The ASRC’s allies in the DOI should give it confidence that the Trump administration is accounting for the ASRC’s financial interests. Tara Sweeney, for example, an ASRC shareholder and the corporation’s most recent vice president for external affairs, was confirmed as the assistant secretary of Indian Affairs on June 28, 2018. In her career working for the ASRC, Sweeney has been intimately involved with the push to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil drilling for decades, even beginning her career56 at a Washington, D.C., firm where she lobbied Congress to open the refuge. During her confirmation hearing, she pledged57 to recuse herself from any work that might benefit the ASRC, including work related to the Arctic Refuge. But—as with many of President Trump’s appointees—concerns about conflicts of interest, transparency, and personal enrichment run deep, so Sweeney’s involvement will need to be closely monitored and scrutinized.

Additionally, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke’s senior adviser for Alaska Affairs, Steve Wackowski, has ties to the ASRC’s seismic application. Wackowski was formerly employed by58 Tulugaq II LLC, a joint venture involving Fairweather Science, Kaktovik Inupiat Corp., and Olgoonik Oilfield Services. The Kaktovik Inupiat Corp. and SAExploration, a contractor59 for Fairweather, have now jointly applied with the ASRC for approval to conduct seismic studies in the Arctic Refuge. These relationships pose serious conflicts of interest as the DOI reviews the application.

Deputy Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt and Assistant Secretary of Land and Minerals Management Joe Balash are also both intimately connected with Alaska and efforts to sell the refuge to oil and gas interests. While working as a lobbyist, Bernhardt represented the state of Alaska in its pursuit for new seismic exploration in the coastal plain.60 Also, while directing the DOI’s Office of Congressional and Legislative Affairs, Bernhardt rewrote61 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) scientific findings to dismiss warnings on the impact of Arctic drilling on caribou herds. Instead, the DOI relied on data from a report funded by BP oil. As former acting commissioner of the Alaska Department of Natural Resources in 2013, Balash has actively petitioned62 the FWS to allow seismic studies in the Arctic Refuge. In light of this, the ASRC has a lot of the DOI’s political appointees in its corner on refuge drilling.

Conclusion

The little-known ASRC has had an outsized role in opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas drilling throughout the history of this fight. In its materials, the ASRC proclaims that “as stewards of this land” granted to the corporation under ANCSA, “balancing management of cultural resources with natural resources is important.”63 Now, it is up to the ASRC to do just that. It must consider and, where possible, support other Alaska Native groups who are not multibillion-dollar corporations but who will have their livelihoods deeply disrupted by development. The ASRC must make it a priority to ensure that subsistence needs are met and that the environmental integrity of the refuge is sustained. It is important, too, that Congress keep a close eye on the DOI’s next steps in permitting the ASRC to do seismic testing. With the DOI moving forward on such an aggressive timeline, and the ASRC in lockstep with them, congressional oversight is critical. The ASRC is ready to do the unprecedented: drill in America’s most pristine wildlife refuge.

Sally Hardin is a research analyst for the Energy and Environment War Room at the Center for American Progress. Jenny Rowland is the senior policy analyst for Public Lands at the Center.

The authors would like to thank Matt Lee-Ashley, Andrew Edkins, Lauren Kokum, and Shanée Simhoni for their contributions to this brief.