Beginning in 2010, more than 40 states adopted the Common Core State Standards. In the years immediately following their adoption, educators, parents, and policymakers familiar with the standards strongly supported them. They recognized the failure of previous education standards to prepare students for life after high school, and they agreed that all students should be held to high expectations and taught the knowledge and skills needed to succeed the 21st century. Both Republicans and Democrats heralded the Common Core as one of the most promising school reforms in decades.

Fast forward to today—a midterm election year—and the Common Core is a deeply controversial topic, despite the fact that the standards have not changed since they were first released. In the past year, two states—Indiana and Oklahoma—have withdrawn entirely from the Common Core, claiming the federal government has poisoned an otherwise positive education reform. In addition, Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal (R) attempted to unilaterally repeal the standards and is now in a dispute with the state education board and the state superintendent.

To understand state legislators’ and governors’ sudden resistance to the Common Core, we must determine the cause. Are politicians creating opposition by associating the Common Core—a state lead effort—with the federal government in order to flex their conservative muscle? Are they trying to motivate resistance to the standards based on political ideologies rather than sound education policy? Or, are politicians simply voicing the concerns of parents and educators who are opposed to the standards because they do not believe they serve students’ best interests?

In order to begin answering these critical questions, the Center for American Progress examined the influence of politics on the Common Core by tracking the popularity of “Common Core” as a Google search term, the number of news articles related to the Common Core published since 2009, and public opinion polls.

Based on this research, it appears that both public interest and opinion of the Common Core reacts to—rather than causes—the politicization of the standard.

Increased interest in the Common Core

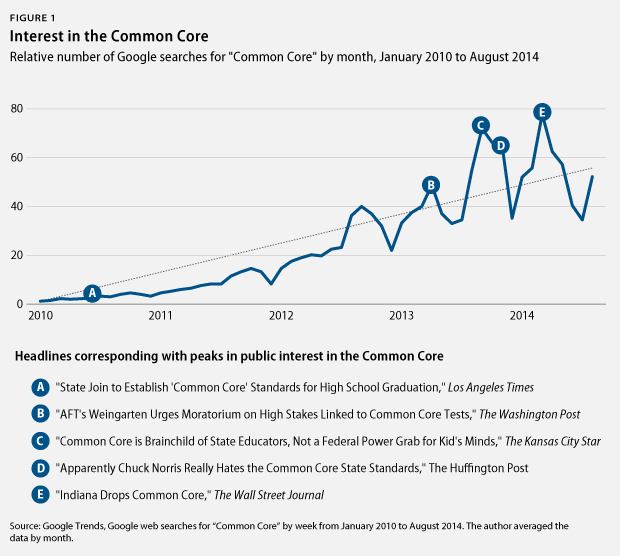

General interest in the Common Core has gradually increased with large spikes around politically charged events and news coverage. As a proxy for the level of public interest in the standards, CAP used data from Google Trends, which measures a topic’s popularity by comparing the number of unique searches for that subject with the total number of searches overall. The graph below tracks the interest in the Common Core from January 2010 to August 2014. Google normalizes the data to range from 1 to 100, with the higher value corresponding with greater interest.

Since 2011, public attention to the Common Core grew considerably. By itself, this is not surprising: As schools moved closer to transitioning to a new set of standards, an increase in public attention is expected. Google Trends identified the headlines listed above as examples of the kind of news articles published during months of peak interest in the Common Core. Taken alone, these particular stories do not account for the growth in public interest but are indicative of the mood of the Common Core debate at that time.

As the headlines demonstrate, each spike in public interest centers on controversial topics that often mischaracterize the Common Core as federal intrusion into state affairs. For example, in The Kansas City Star’s article titled “Common Core is Brainchild of State Educators, Not a Federal Power Grab for Kid’s Minds,” the media coverage focused on the federal role and whether or not the standards are a federal takeover of public schools. The specific headline rebukes the argument that the federal government is responsible for the Common Core, suggesting that there was a considerable outpouring of politicized articles written at that time. This particular example of politicization created a momentary increase in attention to the Common Core that was not sustained. Instead, interest quickly regressed back in line with the larger trend of gradually growing interest in broad education reform, as illustrated by the dotted trend line in Figure 2.

Tracking changes in volume and nature of news coverage of the Common Core

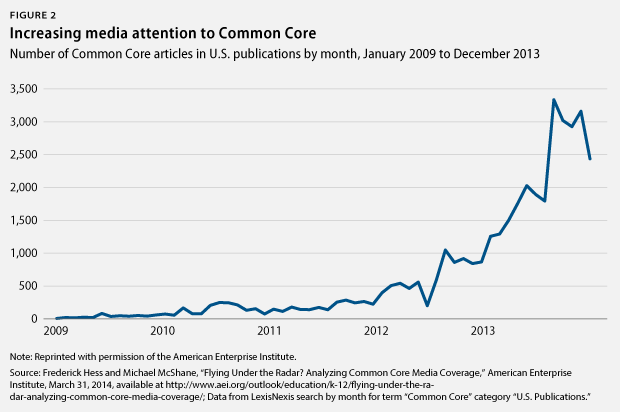

To confirm that the data from Google Trends do in fact reveal patterns in public and media interest in the Common Core, CAP examined the volume of Common Core news coverage. Frederick Hess and Michael McShane of the American Enterprise Institute, or AEI, tracked the number of news articles referencing the Common Core using LexisNexis. They found a significant growth in media coverage of the Common Core beginning in mid-2012, which matches the trajectory of public interest observed through Google Trends.

To determine the nature of the media coverage of the Common Core, Hess and McShane analyzed Common Core articles that included politically charged terms.

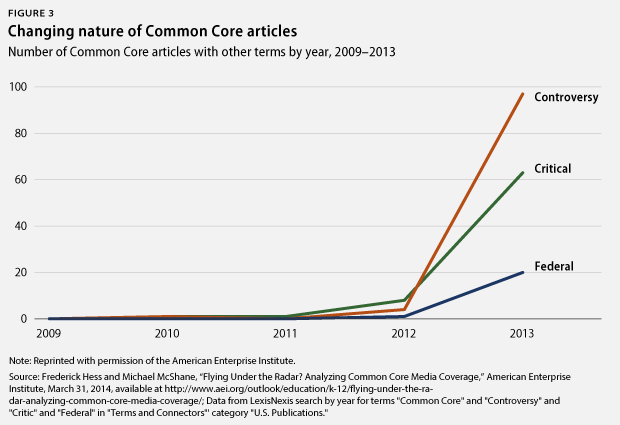

They found that articles linking the Common Core with words such as “controversy” and “federal” skyrocketed in 2012. Although “federal” is not innately political, when it is incorrectly linked with a large state-led education reform, it can engender opposition because it creates the false narrative that public education will be wrested from state and local control. Although Figure 3 is not an exhaustive list of all the terms linked with the Common Core that contribute to the politicization of the standards, the data strongly suggest that media coverage increased dramatically and became decidedly political in 2012.

However, since Hess and McShane did not analyze the increase in politically charged articles with the fluctuations of the public’s interest in the Common Core, they draw the wrong conclusion: They argue that “the coverage of the standards at the outset was generally glowing, rarely referencing any kind of conflict until it had already bubbled over.” In other words, they suggest that prior to the political shift in news coverage, the public was already becoming unhappy with the Common Core.

Yet, the data from Google Trends do not support Hess and McShane’s conclusion. Instead of a “bubbled over” controversy leading to the increased coverage and political nature of news articles about the Common Core, there is an expected, steady increase in public attention to the standards. If Hess and McShane were correct, there would be pronounced jumps in national attention to the Common Core before the news coverage changed in 2012. Rather, the jumps in attention come after the shift in news coverage.

Furthermore, when public opinion polling is introduced into the model, it becomes clear that the politicization of the Common Core sparked momentary increases in public attention to the standards, and not the inverse as Hess and McShane suggest. For example, Achieve Inc.—a nonpartisan nonprofit education organization created in 1996—conducted Common Core voter perception polling routinely from 2011 through 2014. They found that in 2011 and 2012, more than half of voters knew “nothing at all” about the Common Core. Of those who did, 72 percent supported it. In November 2013, at the height of the politicized news coverage, more than 60 percent of voters were aware of the Common Core and 69 percent were in favor of it. If the increased media coverage and the politicization of the debate around the standards were in response to public demand, then there would likely be a drop greater than 3 percent in support for the Common Core. Instead, the portrayal of the standards as a federal power grab, along with the news coverage suggesting a vigorous debate, created controversy where there otherwise wasn’t any.

The most recent round of public opinion polls actually identifies the politics effect, and reveals that the politicization of the Common Core has poisoned the brand; yet, support for the principles of the standards remains constant. A poll released in August 2014 by EducationNext confirmed this: When the “Common Core label is dropped from the question, support for the concept among the general public leaps from 53% to 68%.” This 15 percent gap reveals the politics effect. In sum, the support for what the Common Core seeks to achieve has remained unchanged, given margin of error, from November 2013 to August 2014.

Politicizing the debate leads to politically motivated actions

Increasing public awareness of the Common Core is actually good. The problem, however, lies in how people learn about the standards. A June PDK/Gallup poll reveals that 49 percent of Americans learned about the Common Core through the media compared with only 17 percent who learned from an education professional. As our research shows, media coverage is often partisan and political and pushes erroneous information about the Common Core.

As the Common Core brand became more toxic, governors and other leaders fell prey to politics and flip-flopping. Govs. Jindal and Mary Fallin (R-OK) each offer a case in point. In 2012, when the Common Core was not in the news as frequently or considered particularly controversial, Jindal boldly stated, “Adopting the Common Core State Standards … will raise expectations for every child.” Yet now, in 2014, when Common Core is politicized and divisive, Jindal changed his tune, saying, “I’m against the Common Core, and I don’t want Louisiana to be in the Common Core.” Gov. Fallin made a similar about-face, reversing her long-held support for the Common Core on June 5, 2014, saying, “Unfortunately, federal overreach has tainted Common Core. President Obama and Washington bureaucrats have usurped Common Core in an attempt to influence state education standards.”

Cutting through the politics

Despite the politicization of the Common Core brand, support for the standards and raising expectations for all students remains high. The recently reported decreases in support for the Common Core represents the public’s negative reaction to the political characterization of the standards as a “federal takeover” and not a change in their belief in higher standards for all students. For educators, the faith in the standards persists at a 2-to-1 ratio. Some teachers feel that more work needs to be done in order to fully implement the standards, but more than 60 percent of educators believe the Common Core are the right educational standards for their students.

Support for the Common Core has remained consistently strong because parents and educators know that the previous patchwork of state standards were low quality and did not prepare students for life after high school graduation. Setting a high benchmark is the first step toward leveling the educational playing field for all students regardless of race or ZIP code, ensuring that education is in fact the great equalizer.

The Common Core is a promising student-centered policy that cannot be allowed to fall prey to political polarization. Instead, the nation needs political leaders to make the right decision for children, despite the challenging political circumstances that they helped create.

Max Marchitello is a Policy Analyst for the Pre-K-12 Education Policy team at the Center for American Progress.