Introduction

During his first week in office, President Donald Trump issued two executive orders that greatly expanded on whom the government focuses deportation resources and that also took steps to increase the role of local law enforcement in immigration enforcement.1 These orders essentially enact a policy of mass deportation that affects the entire immigrant population but poses a unique threat to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer, or LGBTQ, immigrants. In general, LGBTQ people have high levels of contact with law enforcement and the criminal justice system. LGBTQ immigrants in particular already face increased rates of policing in the United States in addition to the threat of violence in their home countries if they are deported. President Trump’s orders increase the prospect of entanglement between law enforcement and immigration enforcement and therefore increase LGBTQ immigrants’ vulnerability to violence both in the United States—as a result of overpolicing and fear of reporting intimate partner and hate violence—and abroad through deportation.

LGBTQ people are more likely to interact with law enforcement due to discrimination, overpolicing, and violence

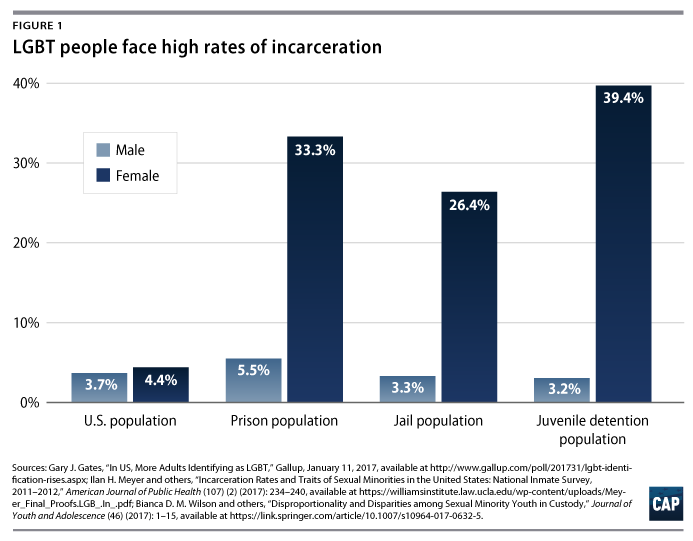

Although 4.1 percent of adults in the United States identify as LGBT, lesbian, gay, and bisexual people are three times more likely to be incarcerated than the general population.2 A large contributing factor to the high incarceration rate of LGBTQ people is the discrimination they face in many aspects of life: from being fired from a job or not hired in the first place to being refused housing because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.3 Without protections for basic necessities, such as employment and safe shelter, LGBTQ people are at risk of being homeless or being forced to rely on survival economies, such as sex work.4

A 2012 study by Lambda Legal found that 73 percent of LGBTQ people surveyed reported face-to-face contact with police within the past five years.5 Forty percent of transgender respondents to the U.S. Transgender Survey in 2015 interacted with police officers in the past year compared with 26 percent of the general population.6 Despite the U.S. Supreme Court striking down state sodomy bans in 2003, LGBTQ people continue to be criminalized through profiling, including of transgender and gender nonconforming people, as well as the discriminatory enforcement of laws, including HIV criminalization laws and indecency laws that target LGBTQ people engaged in consensual sex.7 Nearly half of respondents to the U.S. Transgender Survey who were arrested reported that the police used condoms in their possession as evidence of sex work.8 Twenty percent of respondents to Lambda Legal’s survey reported they were falsely accused during the police contact.9

A 2012 study by Lambda Legal found that 73 percent of LGBTQ people surveyed reported face-to-face contact with police within the past five years.5 Forty percent of transgender respondents to the U.S. Transgender Survey in 2015 interacted with police officers in the past year compared with 26 percent of the general population.6 Despite the U.S. Supreme Court striking down state sodomy bans in 2003, LGBTQ people continue to be criminalized through profiling, including of transgender and gender nonconforming people, as well as the discriminatory enforcement of laws, including HIV criminalization laws and indecency laws that target LGBTQ people engaged in consensual sex.7 Nearly half of respondents to the U.S. Transgender Survey who were arrested reported that the police used condoms in their possession as evidence of sex work.8 Twenty percent of respondents to Lambda Legal’s survey reported they were falsely accused during the police contact.9

Another factor contributing to the increased interaction between LGBTQ people and law enforcement is the high rate of violence they face. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, nearly 1 in 5 reported hate crimes in 2015 were motivated by the victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity.10 The National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs reported that anti-LGBTQ homicides rose 20 percent from 2014 to 2015.11 More than half of the respondents to the U.S. Transgender Survey reported experiencing some form of intimate partner violence.12

Two weeks after President Trump issued his executive orders, Irvin Gonzalez, a transgender woman, was at the El Paso County Courthouse receiving a protective order after alleging that she was the victim of domestic violence. Unbeknownst to her, a U.S. Border Patrol agent was in the courtroom and more were waiting outside.13 Shortly after receiving the protective order, she faced another threat to her safety: She was apprehended by Border Enforcement Security Task Force agents.14 It appears that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, received a tip from her alleged abuser, whom they had in custody.15

Instead of finding protection, after a Border Patrol agent picked Gonzalez up, she was charged with illegal re-entry into the United States and is currently being held by the U.S. Marshals Service in a county jail, where she was not permitted access to the hormone therapy she needed until a judge intervened.16

Immigration consequences of criminal convictions and criminal consequences of immigration offenses

The president’s executive orders not only call for the deportation of all unauthorized immigrants in the United States—including the estimated 267,000 adult unauthorized immigrants who self-identify as LGBTQ—but they also put authorized immigrants who have criminal convictions, no matter how old the convictions are, at heightened risk of deportation.17 The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, or INA, provides grounds for removal of noncitizens based on certain criminal convictions, including crimes involving moral turpitude and aggravated felonies.18 Notably, an “aggravated felony” under criminal law can also include nonviolent misdemeanors, such as consensual sex between a 21-year-old and a 17-year-old.19 “Moral turpitude” is not defined by the INA, but courts have generally defined it to include conduct that is “inherently dishonest, base, vile, or depraved, and contrary to the accepted rules of morality and the duties owed between persons or to society in general.”20 Such a definition is significant for LGBTQ immigrants because it rests on assumptions of the individual’s morality or intent to deceive the judge; both of these assumptions have historically been used to criminalize LGBTQ people.21

In addition to immigration consequences for criminal convictions, certain immigration offenses also can lead to criminal penalties, resulting in prison time as well as detention and deportation. Re-entering the United States after deportation is a felony that carries a maximum sentence of two years and accounts for one-quarter of all federal criminal prosecutions.22

Alternately, unauthorized immigrants who are victims of certain crimes and cooperate with law enforcement can access certain visas that imbue protected statuses. Survivors of domestic violence who are immigrants are often afraid to seek assistance because of their immigration status, causing them to remain in abusive relationships.23 Abusers count on their victims’ fear of deportation to perpetuate their abuse. Under the Violence Against Women Act of 1994, survivors who are abused by a U.S. citizen or green card holder may be eligible to apply for a green card themselves without depending on their abuser.24 Immigrants who are victims of certain crimes may qualify for what is called a U visa if they possess credible and reliable information about the criminal activity and are, have been, or are likely to be helpful in investigating the activity.25 Survivors of a severe form of trafficking may be eligible for a T visa if they are willing to cooperate with the investigation or prosecution of their trafficker.26 Since these protections require cooperation with law enforcement, reluctance to seek assistance from law enforcement due to fear of immigration consequences makes these protections unavailable to victims of crimes. When ICE deports victims of violence or, such as in Gonzalez’s case, when it relies on information that may have been provided by abusers, it goes against the very purpose of laws extending immigration relief to victims of violence and reinforces the abuser’s threats.

Deportation puts LGBTQ immigrant lives at risk

LGBTQ people face widespread persecution in much of the world, with 76 countries criminalizing people based on their sexual orientation or gender identity and expression.27 A report by the Transgender Law Center and Cornell University documents the “pervasive discrimination, hatred, violence, police abuse, rape, torture, and vicious murder” that transgender women in Mexico face. The situation has worsened since marriage for same-sex couples was legalized in Mexico in 2010, with 79 murders of transgender people reported in the two years after Mexico gained marriage equality compared with 13 in the two years preceding it.28 For many LGBTQ immigrants, deportation can be a death sentence, making the criminal consequences of illegal re-entry more appealing than staying in a country where their lives are at risk.

Although protections from deportation for people at risk of persecution exist, criminal convictions can make it harder to obtain protection. Individuals convicted of aggravated felonies are not eligible for asylum and may be ineligible for withholding of removal, a form of protection that allows the beneficiary to remain in the United States with few of the benefits of asylum, even though the burden of proof is higher.29

According to the U.S. Transgender Survey, 32 percent of transgender people who applied for asylum received withholding of removal instead, compared with an overall withholding of removal grant rate of 10 percent immigration courts.30 A study by the Center for American Progress found that 43 percent of transgender asylum applicants in removal proceedings received either withholding of removal or relief from deportation under the U.N. Convention Against Torture, which is available to people regardless of criminal history.31 Since these lesser forms of protection also require meeting a higher burden of proof, these data indicate that transgender asylum seekers have strong protection claims but face barriers to asylum, such as missing the one-year filing deadline, having previously been ordered removed from the country, or having certain criminal convictions that make them ineligible for asylum.32

Johanna Vasquez’s case illustrates the devastating choice that too many LGBTQ immigrants face between risking their lives in countries that are unsafe and risking arrest and deportation in the United States. The entanglement of local police and immigration enforcement funnels LGBTQ immigrants such as Vasquez into a system that itself is often completely unsafe.

Vasquez came to the United States at the age of 16 after being brutally raped in El Salvador.33 As a transgender woman, she believed that the United States would provide safety but did not know that she could apply for asylum. Without authorization to be in the United States, she survived on whatever jobs she could, doing sex work when she could not find other jobs. After 11 years, Vasquez was arrested for having fake immigration documents and jailed with men in the Harris County Jail before being transferred to ICE custody where she went back and forth between solitary confinement and being jailed with men who harassed and beat her. She chose to return to El Salvador rather than remain in those conditions, but the situation in El Salvador for transgender women remained dangerous. She was abducted and gang raped and then sexually assaulted by the police officer to whom she reported the rape.34

Unable to remain safely in El Salvador, she returned to the United States where she was picked up by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, or CBP, agents. Rather than process her case as a civil immigration matter, immigration officials referred her to the Department of Justice for criminal prosecution. Vasquez was convicted of illegally entering the country after a prior removal and was imprisoned before she ultimately was removed from the country. When she returned to the United States a third time, she was again apprehended and imprisoned for illegal re-entry. After serving her prison sentence, she was taken to an immigration detention facility to await a third deportation. Thankfully, this time Vasquez reached Immigration Equality, an organization that assists LGBTQ and HIV positive asylum seekers, and with their help, she was granted withholding of removal.35

The impact of President Trump’s executive orders on LGBTQ immigrants

Under President Trump’s executive orders on immigration enforcement, ICE personnel are directed to pursue the deportation of all removable immigrants but also to prioritize for deportation any immigrant who is otherwise removable and has been convicted or charged with a crime or who has merely “committed acts that constitute a chargeable criminal offense.” In fact, the order allows immigration agents to prioritize any person who is removable and that they believe is a “risk to public safety or national security”—even if that person has not committed a crime.36 To facilitate the administration’s mass deportation agenda, the executive orders not only calls for the hiring of 15,000 additional ICE officers and Border Patrol agents, but they also take steps to expand the federal government’s reliance on local law enforcement to identify and remove immigrants. The executive orders and implementing memos signed by the Department of Homeland Security’s Secretary John Kelly call for the expanded use of 287(g) agreements. These controversial agreements allow state and local law enforcement to enforce immigration laws, measures that, as an earlier CAP issue brief illustrates, lead to great financial costs and diminished public trust, ultimately hurting public safety.37 As described above, given LGBTQ immigrants’ increased rates of contact with law enforcement, these directives disproportionately affect this population. Linking law enforcement with immigration enforcement through the use of 287(g) agreements and policies that encourage local jails to identify and hold immigrants for ICE adds an additional risk for LGBTQ immigrants who are already disproportionately criminalized: It puts them at risk of being deported to unsafe countries.

The increased police contacts and violence faced by LGBTQ people, described above, are compounded by race and immigration status. Legal Services NYC observed that “homophobia and transphobia, combined with being undocumented, puts some low-income LGBT people at greater risk from trafficking.”38 Eight percent of Latina/o respondents to Lambda Legal’s survey were asked by police to prove their immigration status, and 21 percent reported being physically searched during their police contact.39 One-quarter of Latina respondents to the U.S. Transgender Survey who interacted with law enforcement in the past year reported that an officer assumed they were sex workers.40

The risk of violence that LGBTQ people face is also higher when race and immigration status are considered. The rate of reported incidents of hate violence against LGBTQ unauthorized immigrants is rising, from 6 percent of LGBTQ survivors of hate violence in 2014 to 17 percent in 2015.41 LGBTQ unauthorized immigrant survivors of hate violence are four times more likely to have experienced physical violence than other LGBTQ survivors.42 Nearly 1 in 4 unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. Transgender Survey reported being physically attacked in the past year.43 Intimate partner violence among LGBTQ people involving an unauthorized immigrant survivor more than doubled from 2014 to 2015.44

When law enforcement is working with immigration enforcement, LGBTQ immigrants are reluctant to look to law enforcement for assistance, placing them at an even greater risk of violence.45 These fears are not unfounded. Mistaken arrests of LGBTQ survivors of intimate partner violence rose from 17 percent reported in 2014 to 31 percent in 2015.46 Fear of interacting with law enforcement could actually prevent LGBTQ immigrants from accessing forms of protection for survivors of violence that would allow them to lawfully remain in the United States, such as a Violence Against Women Act self-petition, a U visa, or a T visa.47

Conclusion

Collaboration between local law enforcement and immigration enforcement exacerbates the danger that LGBTQ people face. By the administration linking criminal and immigration enforcement, LGBTQ immigrants face profiling and harassment by law enforcement because of their sexual orientation or gender identity as well as their immigration status, further eroding the community’s trust in law enforcement. Beyond the threat of profiling and harassment, collaboration between local law enforcement and immigration enforcement heightens the risk of deportation, dissuading LGBTQ immigrants from seeking the assistance of law enforcement to obtain relief that would allow them to remain in the United States and placing them in jeopardy of being deported to a country where their lives are at risk.48

Cities and counties should take measures to disentangle local law enforcement from immigration enforcement to ensure the safety and security of all of their community members.49

Sharita Gruberg is the Associate Director of the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress.