See also: “Methodology for ‘When Parents Can’t Find Summer Child Care, Their Work Suffers’” by Cristina Novoa

Americans see summer as a carefree time for children, but for working parents, finding summer child care can be a logistical and financial headache. Care is expensive and hard to find, forcing parents to make difficult trade-offs between work and family life.

Joi is one mother who knows this struggle all too well. She and her husband live with their four young children in Jonesboro, Georgia. Joi works full time during the day, while her husband works as a police officer at night, staggering their work schedules to accommodate their child care needs. Although their family has been able to secure regular, year-round child care for their younger children, they are still searching for an affordable summer program for their oldest, 6-year-old Mason. “As of right now I don’t have Mason enrolled in any summer camp. We’re hoping people will drop out of the parks department camp during the first two weeks so that a spot will open up. … I don’t know what I’ll do when I have to find summer care for my four kids,” Joi said in a personal interview.1 With few options available, Joi is left scrambling for a short-term arrangement for her son—and dreading the day when she must juggle summer care for all her children.

Most children in the United States today live in families like Joi’s, where all available parents are in the workforce.2 During the school year, many parents must find child care in the late afternoon and during school breaks. But finding child care when school lets out for the summer—without the six-hour school day and after-school programs to rely on—can be an even greater challenge. For many families, summer child care arrangements are expensive, difficult to find, and out of line with parents’ work schedules.3

The primary challenges that families face in accessing and affording summer child care

How exactly are parents making summer child care work for their families? To answer this question, the Center for American Progress conducted a short survey in May 2019 of approximately 1,000 parents of children ages 0 to 13 using the Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform. (see the methodology memo for additional information)4 This issue brief provides some key results from this survey and highlights the main obstacles that parents face in accessing summer child care. The author then discusses the repercussions of these issues, including impacts on families’ finances and careers as well as on the greater U.S. economy, and advocates for solutions in the form of legislation and government programs related to child care.

The results show that finding affordable child care is difficult, driving parents to make sacrifices that compromise their incomes and job security during the summer months.

The key findings include:

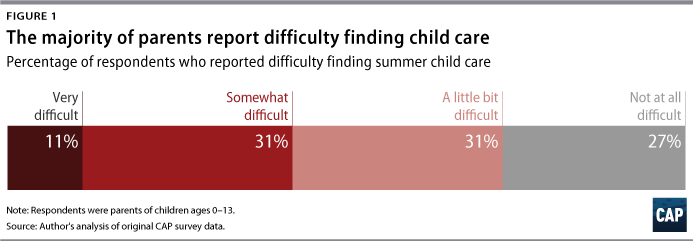

- Parents face barriers to securing care for their children, with 3 in 4 respondents reporting at least some difficulty finding child care during the summer.

- Cost is a common barrier to securing child care, with more than half of respondents reporting that paying for child care is a significant challenge.

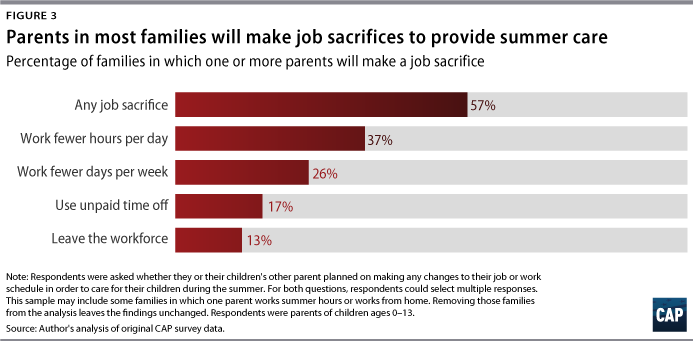

- In 57 percent of families surveyed, a lack of child care means that at least one parent plans to make a job change that will result in reduced income.

Families face numerous obstacles to finding care, such as cost and availability

Finding care is difficult for families; most respondents surveyed—73 percent—reported at least some difficulty. Cost is the most common challenge parents face in securing summer care, with more than half of respondents reporting that cost was a challenge, aligning with earlier research.5 For example, CAP estimated that in 2018, a typical family of four could expect to pay more than $3,000 for summer programs—20 percent of its take-home pay for the entire summer. This is more than double the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ child care affordability threshold of 7 percent of total household income.6

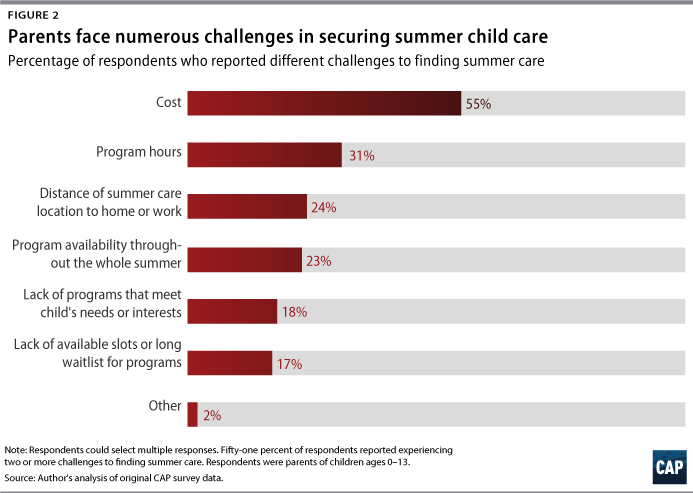

Cost is not the only barrier that families face; availability and access to care are serious issues as well. Programs are often not available during the hours for which parents need care, and they are rarely available throughout the entire summer. Even if programs are open during the times parents need, distance to home or work often makes these options inaccessible. Some parents reported unique challenges, such as difficulties finding care for a child with disabilities. This echoes earlier research showing that parents of children with disabilities report having limited child care options.7 Other respondents expressed concerns around finding safe and reliable arrangements; several noted that typical babysitters, family members, or others they “trust” are not always available during the summer and that a program’s “reputation/safety” are important.8 As Joi describes it, “It’s very scary to take my kid to the park for summer camp since it was totally unknown to me—what it would be like. It’s almost like trial and error, you’re forced to kind of do it because you don’t have any other options.”9

Many families do not have care that fully meets their needs

About 1 in 3 respondents—32 percent—started looking for summer child care early, before March 2019. Considering that summer child care typically does not start until June, this means that one-third of parents started looking for care three months or more before needing it. As of May 2019, one-quarter of respondents reported not having care arrangements that fully met their family’s needs for the summer, despite advanced planning. This aligns with CAP’s earlier research, which shows that kids typically receive summer programming that covers just half of the 10- to 12-week break.10

Most parents make job sacrifices to provide care for the summer

To provide care for the summer, many working parents plan to make job-related changes. Although some of these changes—such as using paid vacation time—have little impact on families’ bottom lines, many others—such as working fewer hours or days per week—result in decreased income for families. The author classifies these latter changes as “job sacrifices.” Survey results showed that in 57 percent of families surveyed, at least one parent plans on making a change to their job that is likely to result in a smaller paycheck, and in nearly one-third of families, both parents plan on making a job sacrifice. To ensure that these results were not driven by families in which parents have jobs, such as teaching, that do not require summer hours, the author excluded those families from this part of the analysis using responses to Question 3 (see methodology memo) and found the results unchanged.

Making job sacrifices that reduce families’ incomes can have consequences for family economic security, as well as for parents’ careers. While this survey did not ask about the respondents’ gender, research demonstrates that mothers are more likely than fathers to leave the workforce or make work adjustments because of problems with child care.11 After taking time away or adjusting their schedules to account for summer child care needs, parents could face barriers to re-entering the workforce at the same level or seeking a promotion or raise in the future. Additionally, for many families, paying for summer programs can be a significant budget item that they do not account for at other times in the year. As Joi describes it, “I have this new bill that I’m not used to having because it’s only for the summer. It’s not a regular budget item.”12 This expense, coupled with reductions in take-home pay for parents, can leave families financially strapped.

The lack of summer child care for American families and the job sacrifices that parents are making as a result could contribute to the larger economic burden of the child care crisis. Each year, American families lose out on $8.3 billion in wages,13 and one estimate finds that the economy sacrifices $57 billion each year in lost revenue, wages, and productivity due to overall child care issues—not just summer care.14

Policy implications

Work does not stop just because school lets out for the summer, and few families have the flexibility in their schedules or the necessary vacation time to take the summer off.15 Families struggle year-round to pay for child care, but during the summer, many more parents are making tough trade-offs to make care work for their school-age children.16 Policymakers can act to support families’ access to affordable child care for their children during the summer, including by implementing the following policies and programs.

Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG): The CCDBG provides funding to states to help eligible low-income families pay for child care, including for after-school and summer care for school-age children. While the CCDBG helps families afford child care, it does not have enough funding to meet the needs of all eligible children, with just 1 in 6 eligible families actually receiving assistance.17 Demand for child care subsidies for school-age children increases during the summer months, with 30 states and territories reporting significant increases in the number of school-age children served through subsidies during the summer months.18 Although Congress doubled funding for the CCDBG in 2018,19 enabling states to serve more eligible families, more is needed to provide necessary assistance to families during the summer months and throughout the year.

21st Century Learning Centers (21st CCLCs): 21st CCLCs provide the only federal funding for community-based after-school and summer programs, which offer students enriching experiences and a safe place to spend time outside of the school day.20 In the 2016–2017 performance period, more than 2 million students and families in underserved communities participated in programs funded through the 21st CCLCs program, including more than 300,000 children during the summer.21 Despite this program’s demonstrated success, just 1.7 million of the 21 million eligible youth—around 8 percent—attend Community Learning Centers due to funding limitations.22 What’s more, President Donald Trump has proposed eliminating this program in each of his presidential budgets for the past three years, though for now, funding for the program is safe.23 Congress should instead bolster funding for 21st CCLCs so that more communities can offer programs that serve children and families during the summer months.

The Child Care for Working Families Act (CCWFA): The CCWFA is the most comprehensive proposed child care legislation to date.24 This bill would limit families’ child care payments to 7 percent of their income and provide parents with year-round, high-quality child care options—including during the summer—to help parents maintain jobs and ensure that their children receive well-supervised and trusted care. An estimated 3 in 4 children in the United States would be income-eligible for assistance under this bill, and early educators would be guaranteed a living wage.25 Passing this legislation, which was reintroduced in the House and Senate last February, would significantly reduce the summer child care burden and help families keep more of their paychecks in the summer months.26

Conclusion

The United States’ child care system does not work for many families, especially during the summer. Families struggle to find affordable, high-quality care that meets their needs and fits their budgets. When they don’t find care, parents are forced to make difficult trade-offs that result in job sacrifices and smaller paychecks for their families. Lawmakers should enact policies that support families’ access to child care throughout the year, including the summer—a step that is crucial for both families and the U.S. economy.

Cristina Novoa is a senior policy analyst for Early Childhood Policy at the Center for American Progress.

The author would like to thank Leila Schochet for her partnership on this project.