Paid sick days and unemployment rates

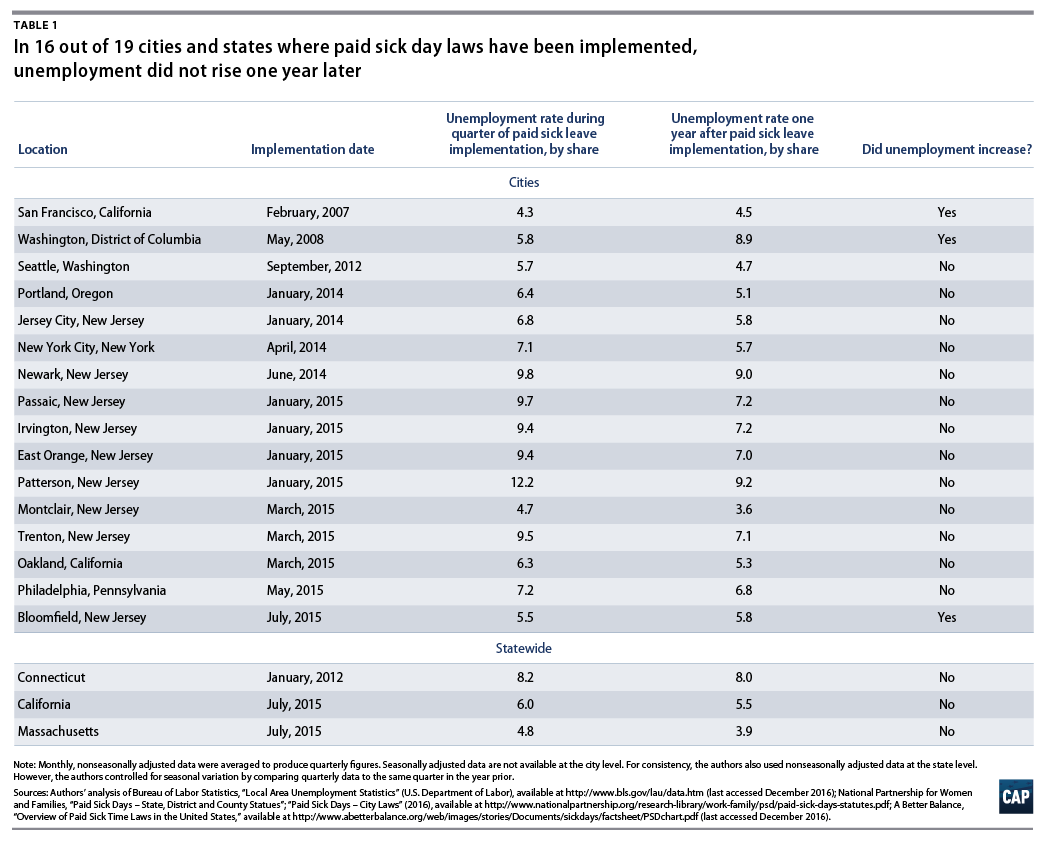

Today, a number of states, cities, and counties have laws that require businesses to provide workers with paid sick days.17 These laws vary in the number of days provided and the characteristics of the employers covered by them. Yet across the board, policies that give workers paid sick time off largely have not been job killers. CAP compared unemployment rates for the quarter in which the paid sick days law was implemented in a given city or state and for one year later in order to understand the overall effect of mandated paid sick leave on the local labor market. As seen in the table below, unemployment did not increase in almost every city and state that passed a paid sick leave law. Rather it appears that these policies do not have significant enough impacts to override other economic forces in the localities where they are implemented.

Table 1 below lists city and state-level laws passed between the first paid sick day law’s passage in 2007 and September 2015, the most recent date for which there was a year’s worth of quarterly unemployment data available at the time of this research.

In 16 out of the 19 localities below, unemployment did not rise one year after the implementation of paid sick days. In 2 of the 3 cities where unemployment did increase—Washington, D.C., and San Francisco—implementation of the paid sick day law directly coincided with the Great Recession. In the other city, Bloomfield, New Jersey, the unemployment increase was very slight. This dispels the idea that such policies directly lead to higher unemployment.

Paid family and medical leave and unemployment rates

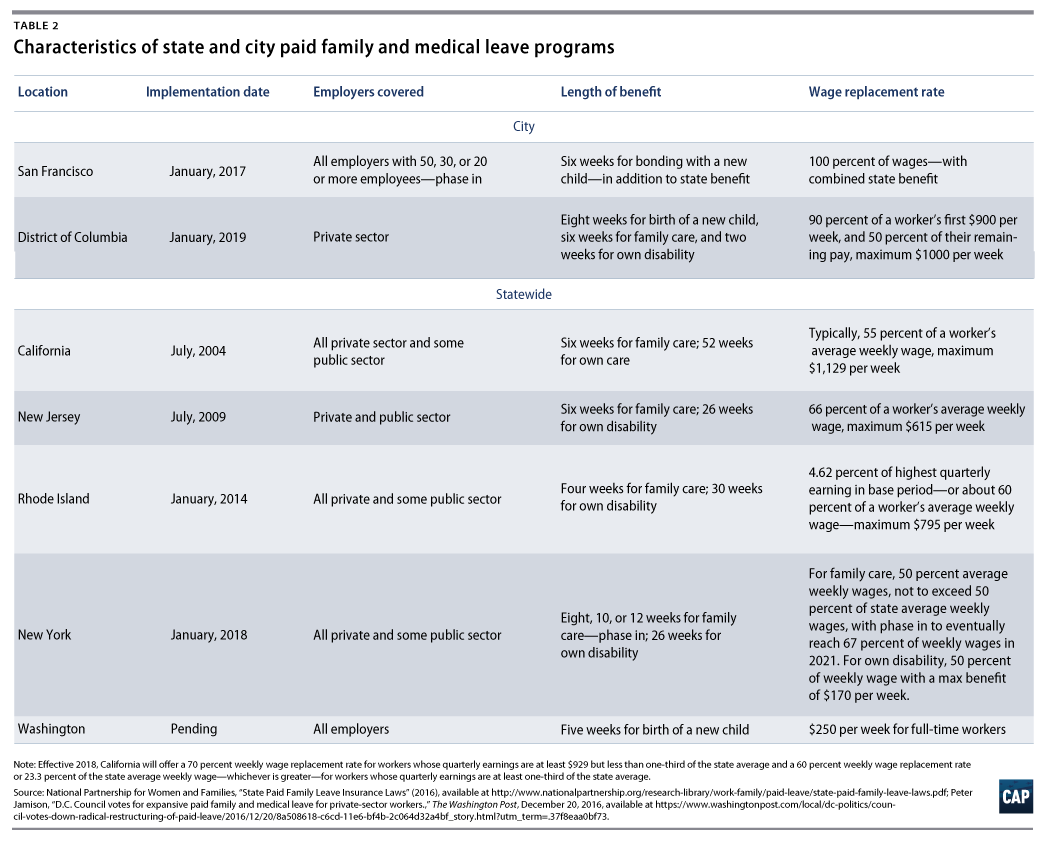

States and cities are also beginning to pass laws that require employers to provide paid family leave to their employees for the purposes of care or bonding with a new child, care of a family member with a serious health condition, or a worker’s own disability. California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island have all passed and implemented paid family and medical leave laws, which vary by state in who is covered, how many weeks of coverage are provided, and the wage replacement rate. The differences are summarized in the table below alongside the laws passed—but not yet implemented—by New York, Washington, the District of Columbia, and San Francisco.

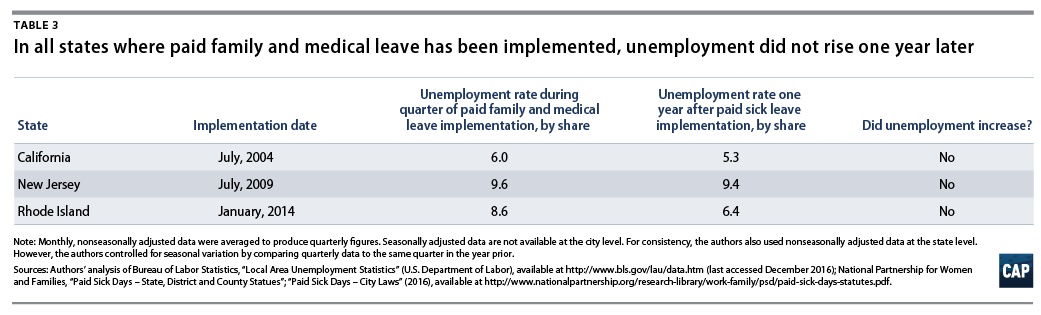

While the programs vary in their wage replacement rates and durations, each represents a significant investment in working families. As seen in the table below, the implementation of paid family and medical leave policies in California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island has not been a job killer. CAP compared the unemployment rates during the quarter of paid family and medical leave implementation with unemployment rates one year later to examine the impact of mandated paid family and medical leave policies on the states’ labor markets. In each state, unemployment statewide did not rise in the year after the policy’s implementation, demonstrating that paid family and medical leave laws do not appear to have any strong negative influence on the labor market.

Table 3 below lists the three state paid family and medical leave policies currently in effect, along with the unemployment rates for the quarter in which they were implemented and for one year later.18 It is clear that paid leave is not a dominant factor in unemployment after implementation and that, in the longer term, other market forces have a stronger impact on unemployment rate levels.

Paid family leave policies for municipal government employees

In addition to the states that have implemented paid family and medical leave policies, many cities and counties have implemented paid family or paid parental leave policies for city or county employees. Notable cities with paid family leave policies for city employees include Boston, Atlanta, Seattle, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, New York, and Portland, Oregon. Municipal governments have also passed paid family leave policies at the county level, such as in Multnomah County, Oregon, and Durham County, North Carolina. Since these policies only impact a small share of the workforce in each city or county, they are not included in CAP’s broader analysis, but they do signal the growing momentum and support for paid family leave policies across the United States.19

Existing research shows that paid sick days do not lead to unemployment

Existing research shows that paid sick days do not increase unemployment and instead may have positive effects on local job markets. In a study of paid sick policies in more than 100 countries around the world, the Center for Economic and Policy Research, or CEPR, found that there was no relationship between the availability of paid sick leave and the national unemployment rate. Instead, countries that provided paid sick leave were more likely to be highly productive and competitive.20 Additional research by CEPR, this time analyzing the experiences of the 22 countries with the highest levels of social and economic development, found no statistically significant relationship between paid sick leave requirements and national unemployment rates.21

Studies from U.S. cities and states that have passed paid sick day requirements show similarly neutral or positive economic effects. In 2016, a comprehensive academic study analyzed data from every U.S. locality with a paid sick days policy to evaluate the claim that these laws cause decreased employment and wages. The authors found, with at least 90 percent statistical probability, that wages and employment did not decrease more than 1 percent across all localities.22

City studies of the economic impact of paid sick leave confirm these recent findings. In 2007, San Francisco became the first city in the country to implement paid sick leave. A study by the Drum Major Institute three years after passage of the measure found that job growth in San Francisco was higher than in the five neighboring counties in the San Francisco Bay Area—Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Mateo, and Santa Clara—without paid sick leave. Between the beginning of 2006 and the beginning of 2010, the most recent period for which data were available at the time of the study, total employment in San Francisco increased 3.5 percent, while total employment in the five neighboring counties fell 3.4 percent. In addition, the number of businesses grew faster between 2006 and 2008—the last year for which business establishment data were available—in the consolidated city-county of San Francisco than in neighboring counties.23 This included both small and large businesses in the retail and food service industries, which are widely considered to be most strongly impacted by paid sick days legislation. The authors concluded that they did not find evidence of a negative business impact in San Francisco due to the implementation of paid sick leave.

Similarly, a study by University of Washington researchers compared Seattle’s economic wellbeing with that of surrounding cities before and after the passage of the 2011 law providing paid sick and safe days—which provide survivors of domestic and sexual violence time off work to seek assistance and leave their abusers—to a large swath of employees.24 The authors found that growth in the number of employers in Seattle was significantly stronger between the third quarter of 2009 and the third quarter of 2013 than the combined growth of three nearby cities—Bellevue, Everett, and Tacoma—which would have experienced the same macroeconomic trends, during the same time period. The law was also shown to have no apparent effect of the number of jobs in Seattle compared with the other group of cities.25

In survey research, businesses also directly report that they do not change their hiring and hours policies in response to paid sick days requirements. A survey of New York City employers after implementation of the city’s paid sick days law showed that more than 91 percent of respondents did not reduce hiring; 97 percent did not reduce hours; and 94 percent did not raise prices as a result of the law.26 In a similar study from Connecticut, which passed a statewide paid sick days law in 2011, employers also reported no effects or modest effects to their bottom lines.27 And an audit of the District of Columbia’s paid sick leave law, effective in 2008, found that it did not discourage business owners from basing their businesses in the District, nor did it incentivize them to relocate their businesses outside of Washington.28

The economic impacts of paid sick days in San Francisco, Seattle, New York City, Connecticut, and Washington, D.C., are largely representative of the experiences across U.S. localities with similar laws.

Workplace benefits of providing paid sick days

Studies from places that have passed paid sick days laws show that they do not have negative economic effects. In fact, paid sick days policies may benefit businesses and local economies by improving productivity, slowing the spread of disease, and reducing job separation and turnover.29

One of the benefits of paid sick leave is a reduction in what is termed presenteeism—that is, when employees go to work sick and are likely to be less productive.30 More than one-third of employers nationwide report that presenteeism is a problem in their organizations.31 The costs of presenteeism are significant and have been shown to be greater than the cost of absence.32 Using the American Productivity Audit, researchers found that $160 billion per year—or more than 70 percent of the total cost of health-related lost productive time—is lost due to reduced productivity at work.33

Moreover, paid sick days may also reduce absenteeism by reducing the duration of illness. A study using National Health Interview Survey data, along with focus group interviews, found that access to paid sick leave is associated with less severe and shortened periods of illness.34

This effect also spills over to other employees, who are at a lower risk of illness when they are less likely to interact with a sick co-worker. Workers without paid sick days are 1.5 times more likely to go to work with a contagious illness than those with paid sick days, and a large majority of employers—87 percent—report that employees who come to work sick have illnesses that are the most easily spread, such as a cold or the flu.35 Unsurprisingly, cities and states with paid sick leave laws have been shown to have lower levels of the flu than comparable cities without paid sick leave laws.36 During the H1N1 pandemic, for example, almost 26 million employed Americans may have been infected. Yet about 8 million of these employees took no time away from work, causing the estimated infection of as many as 7 million co-workers.37

Paid sick days also help reduce turnover, which has significant cost benefits for employers: Replacing an employee typically costs businesses one-fifth of that employee’s annual salary.38 One analysis using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey showed that paid sick leave decreases the likelihood of job separation at least 25 percent and up to as much as 50 percent.39 Another study of female nurses with heart conditions found that those who had paid sick days and/or longer-term paid leave were substantially more likely to return to work after an episode than those without paid leave benefits.40 Businesses that are able to retain trained employees will be able to avoid the costs associated with high turnover.

In addition to academic research findings on the positive business impacts of paid sick leave, direct feedback from business owners confirms that paid sick days largely do not hurt companies’ bottom lines. In a recently released survey of employers in New York City, which passed paid sick days legislation in 2013, nearly 85 percent reported that the law had no effect on their overall costs, and a few employers even reported a decrease in costs. Of those employers who responded that the law did affect their bottom line, most reported an increase of less than 3 percent. Only 3 percent of respondents reported a cost increase of 3 percent or more.41

Labor market effects of paid family and medical leave

While there is little comprehensive analysis of the impact of paid family and medical leave policies on unemployment, those rates did not increase in the three states with paid family and medical leave policies one year after implementation, as seen in the CAP analysis. Previous studies offer insight into other aspects of paid family and medical leave’s impact on employment—especially in the areas of women’s labor force participation, employment-to-population ratio, re-entry into the workforce after having a child, and the duration of unemployment for women when they re-enter the workforce after having a child. Increases in the employment-to-population ratio and the labor force participation rate bode well for economic growth since they reflect a higher share of people employed and looking for work.42 And women’s labor force participation rates in particular have been shown to be key in reducing income inequality.43 CAP analysis shows that income inequality would have grown 52.6 percent faster between 1963 and 2013 if married women’s earnings had not changed.44

According to an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, analysis of paid family and medical leave in OECD member countries and some U.S. states, paid leave increases labor force participation for women—making them both more likely to join the workforce before having children and more likely to return to the workforce after childbirth.45 Across the range of nations included, the study found that paid leave policies increased women’s employment rates around 2 percent on average relative to men.46 A prior study of paid leave implementation in nine European countries found that paid parental leave increased women’s employment-to-population ratios 3 percent to 4 percent.47 A study of Germany’s paid leave law suggested that the increases in employment were especially strong—at 5 percent— for women in part-time employment, suggesting that the policy was particularly impactful for women with loose labor market attachment.48

A subsequent study that centered on California and New Jersey found an increase of 5 percent to 8 percent in those states’ women’s labor force participation rates in the months centered around birth, compared with the women’s labor force participation rates before the laws were enacted.49 These effects were especially strong for less-educated women, who are less likely to have access to paid family and medical leave through their employers.50 These conclusions were echoed in a National Bureau of Economic Research study of the California paid leave law, which found that paid leave increased the probability that women continued in their jobs after childbirth rather than quitting.51 In addition, a study of 324 employed American pregnant women found that the total length of available childbearing leave exerted a strong deterrent effect on quitting the labor force and changing jobs postpartum, especially for mothers having a second or subsequent birth—meaning that longer leaves enabled more women to continue in their current employment.52 One study on California found that while the labor force participation rate rose, the employment impacts were mixed for women of different ages, signaling the need for continued analysis.53 The bulk of the research on paid family and medical leave, however, shows neutral or positive impacts on employment and labor force participation.

By contrast, women who return to the labor market without maternity leave face longer periods of unemployment and earn less over time.54 Broadly, while there are few studies on paid family and medical leave and area unemployment rates in particular, evidence suggests strong positive impacts on employment and labor force participation for mothers.

In addition to the impacts on labor force participation for women, research suggests that paid family and medical leave programs increase women’s wages as well. The National Bureau of Economic Research study on California’s paid family and medical leave program found that the law increased the hours of employed mothers of 1- to 3-year-olds almost 10 percent and may have increased their wages by a similar amount.55 A study based on the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth found that women who take paid leave after child birth are significantly less likely to receive public assistance or food stamps in the year after having a child compared with mothers who do not take leave. The same study found that women with access to leave of 30 days or more were 54 percent more likely to report wage increases in the year after a child’s birth than women who did not take leave.56 By and large, both the research on labor force participation and on women’s wages following the implementation of paid leave policies contradict the conservative argument that paid family and medical leave programs are bad for the labor market.

Workplace benefits to paid family and medical leave

In addition to its positive impacts on women’s labor force participation, paid family and medical leave has positive impacts for businesses. Paid family and medical leave reduces attrition, as seen above, which means significant cost savings for businesses. A previous CAP review of 30 case studies providing estimates for the cost of turnover found that replacing an employee costs businesses roughly 20 percent of that worker’s salary.57 In addition, lowering turnover reduces recruitment and training costs for employers, and it has also been shown to impact productivity and profitability. A University of Cambridge study focused on Britain found that businesses with family friendly policies such as paid leave were more likely to have above average labor productivity than those without such policies.58 Another CAP report looking at 536 midsize manufacturing companies in the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Germany found that those that offered work-family policies typically had higher sales than similar companies in each respective country.59

After the implementation of the paid family and medical leave law in California, the vast majority of businesses reported few or no issues with the costs of the program.60 Nine out of 10 employers reported that paid family leave had a “positive effect” or “no noticeable effect” on productivity, performance, and profitability.61 On turnover and employee morale, 96 percent and 99 percent, respectively, reported either “a positive effect” or “no noticeable effect.” The same study found that 87 percent of employers reported no added costs due to the paid family leave program, and 9 percent of employers reported cost savings.62 Surveys of business owners in New Jersey and Rhode Island produced similar responses.63

For businesses of all sizes, paid family and medical leave programs can have positive impacts. In states without paid family and medical leave programs, small business owners in particular often want to offer paid leave to their employees but are unable to do so outside of a government program.64 A 2013 poll by Small Business Majority found that a majority of small businesses in the state of New York were in favor of publicly administered family and medical leave, and less than one-fourth of them expressed any opposition.65 State and national programs can level the playing field on paid leave and help small businesses offer the benefit without prohibitive costs.66