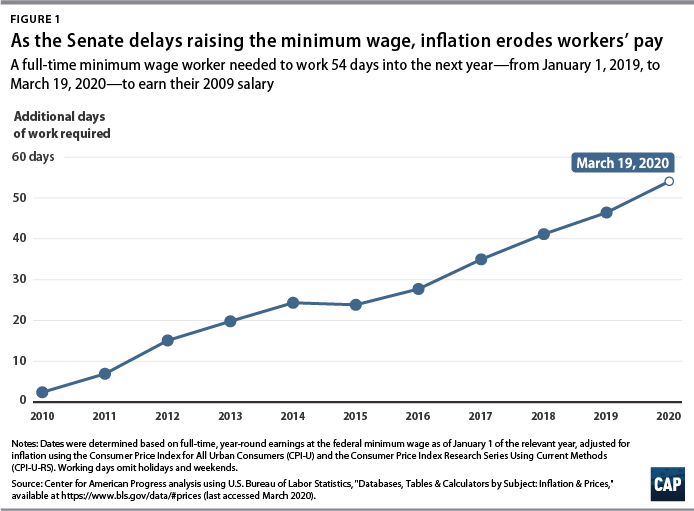

Today marks Minimum Wage Workers’ Equal Pay Day. A full-time minimum wage worker would need to work 54 days into this year—from January 1, 2019, to today, March 19, 2020—to earn their 2009 salary. The federal minimum wage has been stuck at $7.25 an hour since July 24, 2009—the longest period of time that the rate has stayed flat since its creation in 1938. In the nearly 11 years since it was last increased, the minimum wage has lost 17 percent of its purchasing power just because of inflation. While it continues to stagnate at $7.25, the 40 million workers in the United States whose hourly wages are less than $15, who work for tips, and the workers with disabilities who work for the subminimum wage lose out on wages every workday.

And now, the COVID-19 pandemic has sparked an economic crisis that will be felt immediately by those whose wages haven’t kept up with inflation and with increasing costs. Minimum wage workers are on the front lines of a society grappling with a pandemic: Health aides and grocery store workers cannot work from home, and they have little ability to limit their contact with the public while at work. Conservative estimates indicate that up to 3 million jobs could be lost this spring; many of those job losses will be—and already have been—among low-wage workers. Even before the coronavirus crisis began, those workers lost a decade of purchasing power: They have been able to save less because of federal inaction on increasing the minimum wage, and their unemployment insurance will replace wages that are lower than they should be.

There are also significant wage gaps by race, ethnicity, and other demographics that compound wage disparities and push equal pay days later for certain groups of workers. According to the latest census data from 2018, for example, a Latina working full time, year-round earned just 54 cents for every $1 earned by her white, non-Hispanic male counterpart; thus, she will not observe Latina Equal Pay Day this year until October 29. And although the equal pay day date has not been calculated for Hispanic or Latina tipped workers in particular, it is worth noting that they earn just 35 percent of what nontipped white, non-Hispanic men do—creating an even wider wage gap.

In July 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives addressed this decline in purchasing power by passing the Raise the Wage Act: They voted to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour; eliminate the subminimum wage for people with disabilities and those who work for tips; and tie the wage level to inflation for future automated increases, raising wages for nearly 40 million Americans. Crucially, adjusting the level for inflation would protect the future purchasing power of the minimum wage—thereby ending the observation of Minimum Wage Workers’ Equal Pay Day moving forward.

While the Raise the Wage Act languishes in the Senate, workers lose $62 every eight-hour workday earning an hourly wage of $7.25 instead of $15. That’s $310 a week, $1,348 a month, and $16,174 a year. Eliminating these losses would also be a crucial step toward reducing existing pay gaps for women and particularly women of color, who disproportionately work in low-wage and tipped occupations. Until the Senate passes this important piece of legislation, each day marks the longest the United States has ever gone without raising the federal minimum wage. And with every passing day, workers slip further behind.

Lily Roberts is the director of Economic Mobility at the Center for American Progress. Galen Hendricks is a research assistant for Economic Policy at the Center. Robin Bleiweis is a research associate for women’s economic security for the Women’s Initiative at the Center.