Current workforce accountability poorly measures well-being at work

Perhaps it is no coincidence that growing interest in American job quality corresponds with the weakening of employment benefit protections, proliferation of low-wage work, and declining collective bargaining power.5 There is well-established research on the connections between such labor market changes generating widening income and wealth inequality. Mega-economic trends—including automation, globalization, demographic changes, and climate change—have also affected the rapidly changing nature of nonstandard work. Economists Paul Osterman and Elizabeth Chimienti write:

Firms used to view their employees as stakeholders whose welfare had a claim on profits and the gains from productivity, but this is no longer true. Unions have been battered and are less effective. The government has steadily withdrawn from its role of strengthening the floor and upholding employment standards. What all this adds up to is that the forces that might have steadily improved job quality, and wage levels, have eroded.6

For the purpose of this report, conceptualizing job quality—defined as increased earnings and nonmonetary job characteristics—within workforce development policy is grounded in this body of knowledge.

Workforce accountability under current law

Against this backdrop, measures of performance accountability under the current public workforce system serve as poor indicators of job quality, especially when the economy is struggling. During the Great Recession, funding boosts for job training from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) did little to help jobless workers find better employment. Research found that job seekers receiving workforce services at the time were less likely to find work when jobs were fewer than before the recession.7 In their case study of weatherization jobs, Osterman and Chimienti found that while the increased funding for employment and training appropriated under the ARRA increased training standards, “the effort to shape the employment conditions of weatherization work … had virtually no impact on the … job market.”8 As policymakers contemplate various recovery measures, it is vital to weave these past lessons into the structural design considerations required for changing workforce accountability.

The purpose of this section is not to provide a comprehensive overview of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act of 2014 (WIOA)—the nation’s main workforce development law—or the public workforce system; rather, it is to provide a sketch of the system’s accountability markers under current law.9 Specifically, Section 116 of WIOA requires the public workforce system to assess its effectiveness “in achieving positive outcomes” for the individuals it serves based on six primary indicators of performance across six core programs: Title I Adult, Dislocated Worker, and Youth programs; Title II Adult Education program; Title III Employment Service program; and Title IV Vocational Rehabilitation program.10

Among the six primary indicators of WIOA performance, three indicators are employment-related and are most directly connected to the labor market: entered employment, job retention, and median earnings within a certain time frame after program completion. The other indicators measure credential attainment, skills gains, and the effectiveness in serving employers. Importantly, success for the public workforce system is determined by the participant’s record of employment.

It is within this context that the effect of the employment, earnings, and retention metrics are what economists David Howell and Mamadou Diallo characterize as “quantity” indicators designed to “measure the numerical adequacy of” workforce programs.11 Together, these labor market indicators capture an employment outcome in terms of training access and output, pointing to one dimension of job quality. However, WIOA does not require the public workforce system to demonstrate whether decent working conditions—another important dimension of job quality—come with a prospective new job.

Eligible WIOA training providers are also required to offer skills training courses aligned with the needs of in-demand occupations and sectors as determined by their corresponding state and local workforce boards.12 Certainly, this criterion of the law is intended to address skills gap problems that employers tend to frame as a hiring priority. While “in-demand” may be a predictor in job quantity, it offers less indication of job quality. According to recent U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics figures that rank the occupations projected to see the most job growth in the next decade, nearly half of the occupations listed pay less than $30,000 per year.13 Furthermore, the majority of these jobs often lack benefits such as health care and paid leave. Focusing on skills training programs to fill open positions that employers consider in-demand without also guaranteeing workers pay increases, access to basic employment benefits, predictable work hours, and other workforce protections may inadvertently serve to perpetuate an uneven economy that is overreliant on bad jobs.

Reference to the third quarter WIOA performance results for program year 2019 may be helpful. For example, nearly 880,000 adults received employment and training services under the WIOA Adult program, which prioritizes reemployment and training services for low-income individuals.14 More than 70 percent of WIOA Adult participants were reported to be employed a year after exiting the program, and nearly 70 percent earned some sort of educational credential.15 Median earnings were $6,439 in the fiscal quarter after completing the program, amounting to a little more than $25,000 per year.16 Not only were the median earnings of low-wage workers completing WIOA-funded job training about $10,000 less than the real median personal income of $33,706 for all workers, but these earnings convert to an hourly wage that is less than $15 per hour—a minimum yardstick used by advocates for improving living standards for low-wage workers.17

These outcomes parallel findings from a 2017 gold standard evaluation of the Workforce Investment Act of 1998 (WIA), WIOA’s predecessor. The evaluator, Mathematica Policy Research, found that participants receiving the full set of WIA employment and training services were more likely to complete the program and attain educational credentials than the cohort receiving partial services.18 The findings also indicated that the intervention yielded minimal or no gains in earnings, suggesting that, even if a job seeker completes a job training program and earns a credential, they are likely no better off in the labor market.19 For these reasons, the performance of the current workforce system leaves broad questions about the relationship between labor market inequality and declining job quality.20

Additionally, research has shown that the practice of setting standards and managing performance within the public workforce system has for decades led to adverse incentives among practitioners to prioritize, or “cream,” participants who are more likely to be employed with or without services while avoiding serving groups of workers who are more likely to benefit from more employment and training support. This tactic games the system to raise measured performance outcomes.21 In turn, overcoming the combination of these obstacles will entail realizing what systemic approaches are necessary to target good jobs for underrepresented groups, intervene in the marketplace to make bad jobs better, and improve job security for all communities.

Leveraging multiple job quality measures to improve workforce accountability

As described above, this report argues that the existing workforce performance and accountability structure overemphasizes gainful employment with the completion of skills training as a measure of program success while remaining silent as to whether these new job prospects enable workers to achieve good standards of well-being at work. Certainly, some jobs are better than others, and the research studying the relationship between education and improved economic well-being is commonly understood. Access to quality education and skills training can lead workers to higher earnings and good jobs.

However, the legacy of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty and its objectives for helping low-income individuals achieve “self-sufficiency” has left a narrative policy framework across social policy programs, including education and training, that shifts blame for low-quality jobs to workers themselves.22 That is, a perceived lack of career readiness, learning disability, low literacy, and other soft-skill gaps by the public workforce system are operationally considered employment barriers to individual self-sufficiency. As a consequence, however, skill deficiency presumptions baked into workforce policy neither sufficiently account for labor markets that allow for widening wage gaps, occupational segregation against women and people of color, and a growing absence of employment benefits nor do they directly solve for these working conditions.

This section illustrates why the U.S. workforce accountability approach should shift away from its focus on individual skills attainment to assessing the quality of the job match and why this new approach can serve as a proxy indicator of increased equity.

Existing frameworks to draw upon

The concept of job quality may seem elusive without any grounding. In the European Union, as well as in other member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), ensuring job quality is considered a top policy priority, and fostering good jobs is central to the overarching jobs strategy.23 Specifically, the OECD measures and assesses job quality along three dimensions, including earnings quality.24 The framework considers how much a worker’s level of earnings affects their well-being or, in other words, raises their living standards.

Labor market security, which measures the probability and expected duration of job loss, is another dimension of the OECD framework. This is a measurement of the economic cost of job security relative to unemployment for the worker. The third OECD dimension captures working conditions by considering noneconomic elements such as stress on the job, health and safety risks, and whether enough resources are available to complete job responsibilities.

Indeed, multiple forms of measuring job quality exist, from variations in theoretical frameworks to operational databases. The Aspen Institute’s Job Quality Tools Library offers a vast range of resources and guidance for practitioners who have a stake in improving job quality through workforce development.25 The Urban Institute offers another framework for understanding linkages between job quality, worker well-being, and economic mobility by organizing the concept of a good job around five themes: pay, benefits, working conditions, business culture and job design, and on-the-job skill development.26

Defining and measuring the creation of quality jobs

Measuring employment generation, including tracking job creation or preservation, is a normal practice in the field of impact investing in community development. Rather than just counting the jobs created from these investments, the social enterprise group PCV InSight has for more than two decades engaged in a kind of impact-advisory practice in service of both driving capital and doing social good.27 More recently, the organization developed a specific resource for community development foundations, institutional investors, nonprofits, and fund managers on how to define and measure job quality in working with community development financial institution investor companies.28

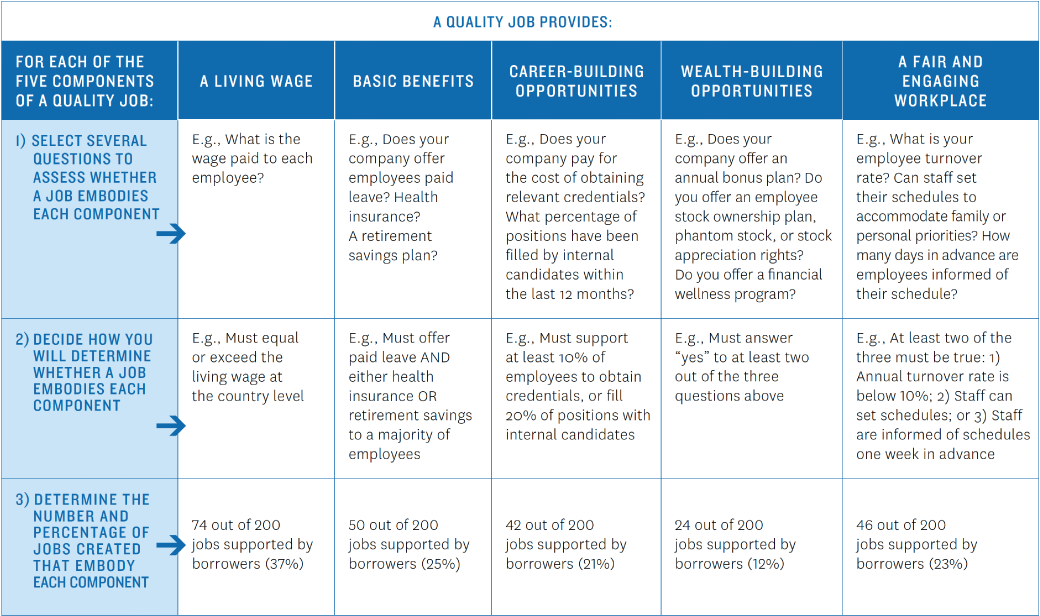

In “Defining and Measuring The Creation of Quality Jobs,” PCV InSight defines a quality job as containing at least three of these five characteristics:29

- A living wage—at minimum, above the industry’s median wage—to support a decent standard of living

- Basic benefits at work, including paid leave, health insurance, and a retirement savings plan

- Career-building opportunities at work, including in-house or external workforce education and opportunities for promotion

- Wealth-building opportunities such as offering profit-sharing

- A fair and engaging workplace such as offering flexible and predictable schedules, ensuring equal treatment, actively soliciting employee consultation, and conducting performance reviews

Operationalizing these components into metrics provides actionable data to understand the extent to which impact investors are supporting quality job creation. To help investors understand whether their investments are actually supporting quality job creation, PCV InSight outlined three steps to ensure the right systems are in place to measure the quality of jobs:

- Choose questions to assess whether a job embodies each of the five components for borrowers and investees to consider during underwriting or due diligence, and review annually after receiving a loan or equity investment.

- Create definitions to help determine whether a job embodies each component.

- Analyze results to determine the number and percentage of jobs created that embody each component.

To further contextualize the different dimensions of job quality, a variety of indexes that provide composite measures of multiple indicators may serve as useful resources for policy development. For example, researchers at Cornell University and the University of Missouri, Kansas City created the U.S. Private Sector Job Quality Index (JQI) to track the quality of jobs every month. Instead of just looking at the quantity, the JQI compares the ratio of “high-quality” versus “low-quality” jobs. By looking at the weekly dollar income a job generates for an employee, the JQI distinguishes between higher-wage, higher-hour jobs and lower-wage, lower-hour jobs to assess job quality.30

If considering job quality in any manner, the Levy Institute Measure of Economic Well-Being (LIMEW) at Bard College may offer policymakers another approach to reconceptualizing workforce accountability. The LIMEW includes estimates of public consumption, noncash transfers, and household production as well as the attributed income that wealth generates.31 In another example, more than 30 years ago, sociologists Christopher Jencks, Lauri Perman, and Lee Rainwater proposed an index of job desirability, which takes a weighted account of both monetary and nonmonetary job characteristics that the “average American worker” considers important.32

As a brief matter of methodological consideration, economists Rafael Munoz de Bustillo, Enrique Fernandez-Macias, Fernando Esteve, and Jose-Ignacio Anton are mindful to illustrate connections between the construction of job quality indices and the interaction between job attributes and social institutions. They write that:

[a] given working schedule might conflict or not with the employee’s work-life balance depending on the existence of a sufficient and affordable supply of nursing homes and kindergartens to whom the worker can entrust the care of the dependent members of the family while at work. If there is a wide ranging [program] of public kindergartens, or a helping retired grandmother or grandfather willing to watch over the younger ones while their parents are working, the lack of family-friendly provisions at work might not interfere with the work-life balance of workers.33

In other words, the social context should always be considered, as jobs exist within public and private institutions. Therefore, the impact of any job characteristic on a worker’s well-being depends on the interplay of institutional characteristics across the broader ecosystem.

The example from Bustillo and others is applicable to workforce development policy and the inherent social nature of employment relationships. Labor force outcomes—initial employment, wage levels, and continuing employment—counted under the current accountability system might have different implications on well-being if labor and employment standards were stronger.

Data dashboards and multiple metrics

Operationally, new indicators could be introduced while existing measures could be improved from existing databases, potentially avoiding the additional costs of developing new surveys or measuring tools. Instead of merely tracking median wages, for example, JQI and LIMEW data could be integrated into a dashboard of indicators that the public workforce system could use to capture multiple dimensions of job quality and monitor its improvement in this area.

The use of data dashboards is a standard practice for driving business performance. Application of data dashboards into business intelligence (BI) systems—transforming raw data into meaningful and strategic information—“directly supports sense-making and decision-making,” according to BI scholar Jack Zheng.34 He describes data dashboards as differentiated into three main types based on purpose, data, and design considerations.

Operational dashboards display data that facilitate the operational side of a business, monitoring operational activities and statuses as they are happening. Establishing an operational data dashboard in the workforce context could provide views of important operational indicators that focus on current performance and are action-oriented. Overview dashboards offer another vantage point by providing a high-level summary of performance represented by key performance indicators. Analytical dashboards are another kind of format that provide a visual analysis of a large amount of data, allow users to investigate trends and establish targets, predict outcomes, and set goals.

K-12 education data dashboards

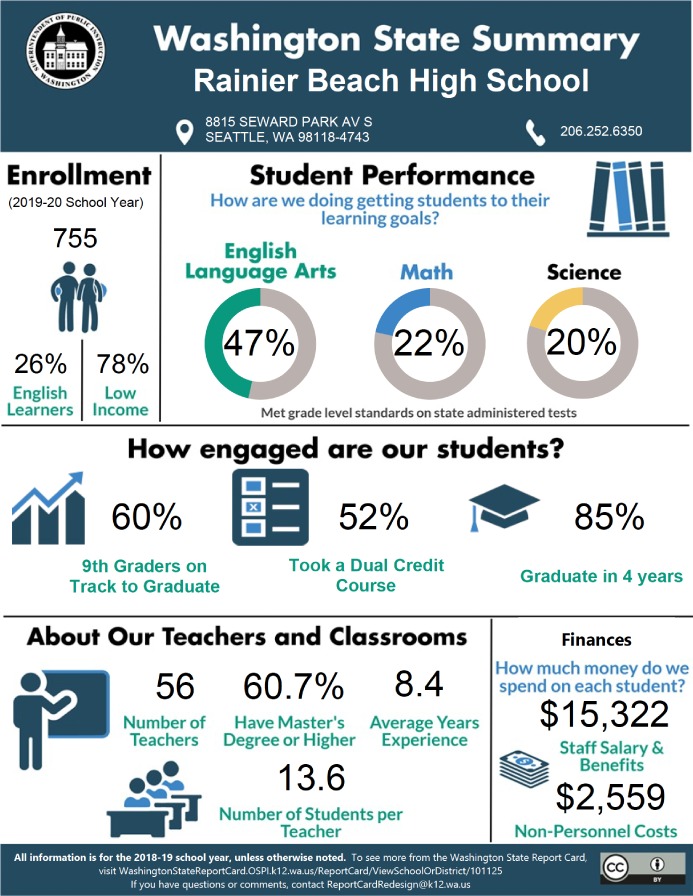

The concept of data dashboards and the use of multiple measures has already been embraced by the public K-12 education system. Beginning with the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB), the federal government has required states to report school performance across different indicators and use those indicators to hold schools accountable for performance. While NCLB’s measures were typically limited to academic assessments, graduation rates, and student attendance, the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) in December 2015 significantly expanded the variety of measures that states must report and use for accountability. Educator and education scholar Linda Darling-Hammond contends that “ESSA has the potential to make the education of young people—students of color, low-income students, English language learners, students with disabilities, and foster and homeless youth—a top priority.”35

In some cases, an overemphasis on state standardized assessments as a predominant indicator can lead to “unintended consequences, such as educators narrowing the curriculum to focus on tested subjects … concentrating resources on the ‘bubble kids’ or students on the cusp of passing the high-stakes tests … and teaching test-taking skills divorced from the content being tested,” suggests education researcher Soung Bae.36 Under ESSA, states are required to develop systems for measuring student progress and improving school performance using multiple measures.

In addition to evaluating student and school progress based on traditional test scores and graduation rates, states must also include one or more indicators of “school quality or student success.”37 Under current law, this indicator may measure one or more of the following:

- Student engagement

- Educator engagement

- Student access to and completion of advanced coursework

- Postsecondary readiness

- School climate and safety

- Any other indicator that meaningfully differentiates between schools and is valid, reliable, comparable, and statewide

Additionally, ESSA requires states to issue school report cards with a much wider array of indicators than those used explicitly for rating schools, such as information on education qualification, per-pupil expenditure, and postsecondary enrollment. Designing multiple measures is an innovation in accountability in that it can help reveal poor learning conditions and other inequalities while also serving as an incentive for states to expand students’ access to early learning opportunities. Examples include access to a high-quality college and career-ready curricula and highly effective teachers, as well as looking into indicators of parent and community engagement.38 “A skillfully designed dashboard of indicators can provide objective, measurable ways for schools, districts, and states to identify challenges and solutions to close opportunity gaps,” says Darling-Hammond.39

The multiple measures approach could similarly be applied to workforce accountability, which could address labor market inequalities plagued by bad jobs that pay low wages and lack benefits. Because these jobs are often disproportionately filled by people of color, leveraging data-informed decision-making through multiple measures could ensure that workers who face systematic obstacles to getting good jobs end up in better working conditions and with improved career options. In particular, a job quality dashboard could present analytics in such a way that policymakers may visualize and gain insight into the patterns, trends, and other complexities of how structural policies mitigate—or reinforce—employment bias.

Furthermore, the use of a data dashboard could help determine which job characteristics are prioritized by state and local workforce areas, identify which practices are incentivized, and inform what policies and supports are provided to ensure that individual needs and economic inequality are both addressed through workforce development. Drawing on racial equity research from Race Forward—specifically, a perspective taken from its key expert interviews with a practitioner in the workforce field—offers additional insight into why policy change is warranted:

Tracking racial outcome data is a larger question that we grappled with. There are studies that say if a client is in post-secondary education for a year, there’s a correlation to higher wages. But there isn’t a specific focus on communities of color. For example, how do outcomes play out in immigrant communities versus heavily populated Black communities? Barriers are different. Language barriers are different. We have a really hard time finding this kind of data. Former studies tend to be race neutral. Having this data would be super helpful.40

For the purposes of evaluating the degree of equity in workforce performance for different groups of workers, tracking multiple job quality metrics through the use of data dashboards could help drive a process of continuous feedback that could transform workplace structures. For example, because WIOA requires training programs to report disaggregated data, a multiple measures dashboard could help organize it in an easy-to-digest visual format for interpreting key trends and patterns at a glance.41 As described above, designing such a data platform doesn’t have to mean coming up with new data sources, as data-sharing agreements can enable the public workforce system to make full use of existing datasets from institutions already engaged in measuring different dimensions of job quality.

In fact, Section 116(b)(1)(A)(ii) of WIOA permits states to develop additional indicators of performance. Workforce policy scholars Dan O’Shea, Sarah Looney, and Christopher T. King profiled 10 states that previously designed and implemented nonfederal workforce performance measures under WIA.42 More recently, at the local level, San Francisco, Dallas, Chicago, and Boston, among other cities, have formed working groups, in partnership with PolicyLink and the National Fund for Workforce Solutions, to create workforce equity metrics and disaggregated data profiles to uncover what drives inequities and develop strategies to address them.* The Seattle-King County Workforce Development Council recently conducted an equity metrics scan to help inform its own efforts to adopt a set of measures aimed at advancing equity.43

Equal employment metrics

For another potential data source, curious workforce redesigners can turn to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and its inventory of existing workforce data that are collected from employers with at least 100 employees and from federal contractors with at least 50 employees.44 The mission of the EEOC is to eliminate discrimination based on a multitude of demographic factors and conditions of employment through data collection and enforcement.

In particular, the EEOC’s EEO-1 report provides a count of employees by establishment and job category, disaggregated by race, ethnicity, and gender information.45 The EEO-1 report also collects data on full- and part-time employees by demographics based on pay band and job category as well as their hours worked. Although EEOC workforce data are confidential, aggregated data are publicly available.

As an example of turning EEO-1 data into a metric, management scholars E. Holly Buttner and William Latimer Tullar developed the diversity metric (D-Metric) to help firms assess their own demographic representativeness in occupational categories compared with the demographics of their relevant labor markets.46 In practice, Buttner and Tullar envision applying the D-Metric to help human resources staff monitor the effectiveness of workforce recruitment within firms.

While the EEOC collects workforce data on multiple factors, these data are far from comprehensive. Gaps in data collection and disaggregation remain,47 such as information about sexual orientation and gender identity48 and inconsistencies with definitions of disability.49 However, with the EEOC’s inherent civil rights mission, using EEO-1 workforce data to help assess demographic distribution by occupation would reinforce equity goals underlying a workforce accountability redesign. Specifically, an EEO-1 metric would facilitate understanding quality as it would provide a statistic for progressing toward a more representative workforce.

Jobs-housing fit metrics

Understanding the challenges workers face in relation to the proximity of their jobs and tracking housing stability offer other ways by which to measure job quality. Housing affordability research finds that low-wage workers spend a greater portion of their income on housing and transportation than those employed in high-wage jobs.50 To the extent that local housing prices match the ability of the local workforce to afford it, enabling the use of such a jobs-housing fit indicator would help shine a light on the availability of quality jobs within a local labor market area.

Seminal research from urban planning scholars Chris Benner and Alex Karner and their development of the “low-wage jobs-housing fit” metric has helped to demonstrate that while parity in housing and job inventory is important, livable wage standards and housing affordability are equally important.51 Their evaluation of housing supply in San Francisco showed that severe shortages of affordable housing in expensive cities often push low-income workers—especially people of color—out of neighborhoods, thus prolonging their commutes to work. By better understanding how housing production aligns with the income of available jobs within the same geography, workforce systems can help not only promote housing security but also influence employment stability.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the rental market illustrates why understanding renters’ financial stability relative to available good jobs can provide an important marker of well-being. For example, a recent Urban Institute survey showed that young adults and people of color are not only disproportionately renters but also face greater difficulty paying rent and are more vulnerable than homeowners to the economic shocks of the pandemic.52 In implementing an economic response to the coronavirus-induced recession, the jobs-housing fit metric would enable an accountability redesign to consider the impact of housing on workforce recovery efforts.

Partnership effectiveness metrics

Quality partnerships between employers, workers, and workforce intermediaries are a precondition for ensuring that high-quality jobs are equally available to any job seeker. In the education sector, the Wallace Foundation created the Partnership Effectiveness Continuum (PEC) to help schools understand how improving the quality of partnerships can support and improve teacher quality. There are six dimensions of partnership effectiveness according to the framework: partnership vision; institutional leadership; joint ownership and accountability for results; communication and collaboration; system alignment, integration, and sustainability; and response to local context as essential to supporting the development of highly effective partnerships.53 With corresponding indicators and criteria under each dimension, the PEC model offers another application for how workforce administrators can distinguish partnerships with employers and training providers that are effective at improving job quality from those that are less successful.

Based on case study research, a 2020 CAP report describes how successful partnerships between workforce intermediaries and employers have three elements in common:

- Partnership is conditioned by a set of job quality commitments, including hiring with higher wages, fringe benefits, workplace safety training, customized training, and future career options.

- Partnership is intentionally built on a client-centered approach with employers that prioritizes quality job conditions and not just the quality of work.

- Partnership development is constant, making sure employers feel that they had a direct hand in forming their firm’s workforce strategy.54

Project Basta: Using effective partnerships to diagnose and assess good job matches

Recent graduates must overcome a wide range of job-hunting hurdles after college. First-generation college students, who often come from low-income or immigrant families, may find the cultural norms for finding a career path after college unfamiliar. Through data-driven performance management, the New York-based Basta program bridges first-generation college seniors and recent graduates with good jobs in growing careers using metrics to help translate their experience to employers.55 Basta recognizes that the resourcefulness, independence, and leadership qualities that first-generation students bring are skills that matter for successful career navigation.

The Basta model focuses on more than just credential attainment; it strengthens the job search strategy and creates a strong metrics-driven dashboard of multiple measures for ensuring quality career pathways first. The Basta framework for improving these workforce connections considers four measurable dimensions: job search exposure, job search interaction and engagement, job search progress and accountability, and hiring outcomes.

Operationally, the first dimension is carried out as an early assessment of career awareness, collecting basic demographic information and creating participant profiles with descriptions of their career exposure experiences. The second measurable dimension of connection tracks participant interactions with the Basta job board, a suite of full-time career coaches and a growing volunteer community cultivated through a variety of networking and skill-building events, all of which offer insight into how they learn about new jobs, their interest and fit for jobs, and then how they apply for them.

In following up with participants to better understand their own career identity and exploration or building in a cohort space to sharpen interviewing and networking skills, the framework provides Basta with a third set of diagnostic information that may be used to refine the specific supports individual students need in their job search and employment-matching process. Being attentive to the hiring commitments of employer partners through participant report outs and updates helps enhance Basta’s ability to make data-informed decisions around tailoring employer outreach, including recruitment support of prospective candidates from the program.

With an eye toward improving job quality for first-generation graduates of color, Basta has been able to track a suite of intensive professional placement and career mentoring services into a centralized performance management system and turn the data collected into actionable analytics. These efforts focus recruitment from largely untapped talent pools while also supporting employers seeking to diversify their workforce through hiring commitments, retention supports, and promotion opportunities.

Effective partnerships can lead to a shared vision, build trust, and leverage scarce resources to focus on joint-improvement strategies. For example, joint labor-management training is a proven partnership model that is based on a cooperative relationship between worker organizations and multiple employers.56 Including partnership effectiveness, such as by encouraging labor-management partnerships, among a dashboard of multiple measures of job quality would help distinguish a new workforce system that is committed to improving outcomes for individuals with barriers to employment.

The gap between equity and workforce systems’ performance has much to do with the current slate of labor market indicators that make workforce accountability determinations. Enabling workforce systems at the state and local levels to create a data dashboard and choose from multiple job quality measures is a mechanism design approach that would reward and recognize as high performing those workforce systems that foster equity.