Infant mortality and mass incarceration are major issues affecting the black community. But while they are often thought of and dealt with on separate tracks, structural racism firmly connects these critical issues. Structural racism exposes black women to distinct stressors—such as contact with the criminal justice system—that ultimately undermine their health and the health of their children. Today, infants born to black mothers die at twice the rate as those born to white mothers.1 This horrific disparity cannot be fully explained by differences in income, education, or even health care; evidence suggests that cumulative stress from generations of structural racism is driving this epidemic.2 To combat this persistent problem, lawmakers must attack structural racism in all its forms—including mass incarceration.

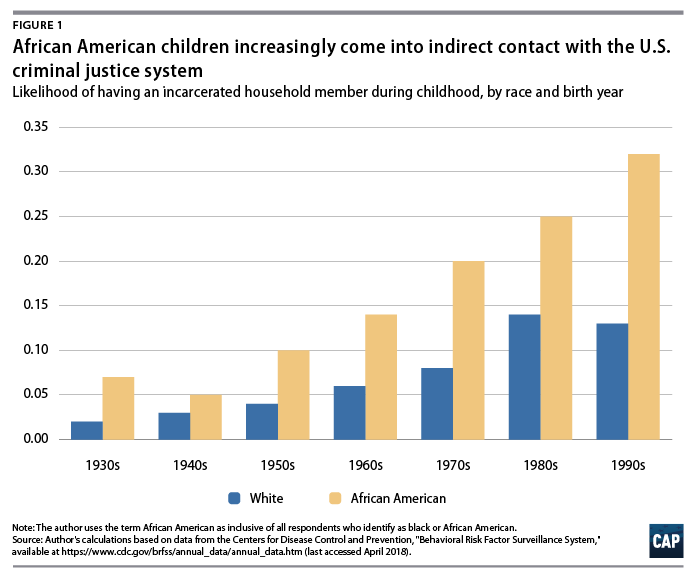

Structural racism is defined as a system of public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms that work in reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial inequality.3 The criminal justice system is perhaps the clearest example of structural racism in the United States. The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world, and the overwhelming burden of contact with the system has fallen on communities of color, especially African Americans.4 African American adults are five times more likely to be imprisoned than white Americans.5 According to data detailed in this issue brief, African Americans are twice as likely as their white counterparts to have a family member imprisoned at some point during their childhood.6 With overall incarceration rates more than 500 percent higher than they were forty years ago, black Millennials and post-Millennials are at greater risk of contact with the system than any previous generation.7 In fact, a new CAP analysis finds that 1 in 4 black Millennials had an incarcerated loved one before they even turned 18. For those born in the early 1990s, the rate is almost 1 in 3.8 (see Methodology)

Mass incarceration has long-term physiological effects that contribute to a range of health issues, including mental health disorders, diabetes, asthma, hypertension, HIV, and Hepatitis C.9 Although not as well-studied, mass incarceration can also directly and indirectly affect infant mortality. While its direct effects are well-documented, its indirect effects are pervasive and damaging but largely unrecognized. When incarcerated, an individual can face increased risk of sexual violence and infectious illness; loss of connection with family and friends; as well as trauma resulting from draconian prison policies and practices. Furthermore, the incarceration of a loved one or breadwinner can cause families and friends significant emotional distress, loss of income and property, and residential instability. These experiences put affected individuals at a heightened risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression.10

Based off new analysis and existing evidence, the Center for American Progress believes the toxic stress from contact with the criminal justice system has contributed to the disparity in rates of black and white infant mortality.11 In fact, experts estimate that infant mortality rates today would be 7.8 percent lower and that disparities between black and white women would be 15 percent smaller if incarceration rates had remained at 1970s levels.12 Targeted interventions are necessary to close the gap and bring the United States up to par with other developed countries.

This issue brief presents a new CAP analysis and summarizes existing research to detail the effects of mass incarceration on black women and children. In particular, it highlights how black women’s heightened contact with the criminal justice system leads to increased stress and disparities in health and infant mortality. Like most analyses, some data limitations exist and are detailed at the end of the brief.

Mass incarceration affects millions of black women and children

Structural racism exposes countless black women and children to the harmful stressors associated with the criminal justice system. The number of incarcerated U.S. women overall has increased dramatically in recent decades—from just 26,000 in 1980 to 219,000 in 2017.13 Perhaps unsurprisingly, the spike in female incarceration has disproportionately affected black women, especially young black women. While black women overall are twice as likely to be imprisoned as their white counterparts, black women ages 18 to 19 are three times more likely to be imprisoned than their white counterparts. If current incarceration trends continue, 1 in 18 black women will be imprisoned at some point in their lifetime.14

Black women and their families, especially within younger generations, are also more likely than their white counterparts to have indirect contact with the criminal justice system through the incarceration of a household member. According to new CAP analysis of data from nine states, African American children across generations have had more than twice the odds of having an incarcerated household member as white children.15 This is true even after controlling for income level; geography; and family history of addiction, mental illness, and abuse. The data also reveal that younger generations are at greater risk, with 27.4 percent of black Millennials having indirect contact during childhood, compared with 10.7 percent of black Baby Boomers.

A related CAP analysis found that racial disparities in indirect contact with the criminal justice system persist long after childhood. In fact, more than 1 in 4 African American baby Boomers—26.4 percent—report having an immediate family member incarcerated at some point in their lifetime, compared with just 15.1 percent of white Baby Boomers.16 Large disparities exist even after controlling for other important variables, such as income and education. As Millennials and post-Millennials have come—or are coming—of age during a period of mass incarceration, they will likely report even higher rates of contact with the system during their lifetimes.

Contact with the criminal justice system increases women’s stress levels

Millions of black women are exposed to the harmful effects of mass incarceration during their lifetimes. Whether they experience imprisonment personally or they have an incarcerated loved one, contact with the system is a significant stressor that undermines the long-term health of mothers and their children.

Direct contact with the criminal justice system

Contact with the criminal justice system is stressful no matter one’s economic status, race, gender, or age. However, as important groups like SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective and the Center for Reproductive Rights have highlighted, many women—especially black women—are exposed to unique stressors when they are incarcerated.17 For example, 86 percent of incarcerated women are survivors of past sexual violence, but they are still subject to procedures that fail to consider past trauma. These procedures can include cavity searches, pat downs, and shackling.18 In addition, most jails and prisons lack adequate mental health services, menstrual hygiene products, or gynecological and obstetric care—compounding the stress and trauma experienced while incarcerated.19

Furthermore, the vast majority of incarcerated women are also mothers—mostly to young children.20 Prior to incarceration, most of these women were the primary caretakers of their children.21 But half are confined in facilities located more than 100 miles from their families, and more than one-third (38 percent) will not see their children even once while incarcerated.22 Lack of regular contact with their children heightens stress levels among incarcerated mothers.23 To make matters worse, many siblings are split up when a mother is imprisoned.24 When this occurs, incarcerated mothers are four times more likely to experience high levels of maternal strain—or significant stress from feeling like they are not fulfilling their obligations as a mother.25 In addition, if children are placed in foster care, incarcerated mothers risk never getting them back, even if they are able to demonstrate the ability to care for them upon release.26 Black mothers are already far more likely to report depression than the general population.27 These stressors only exacerbate this persistent problem.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 4 percent of women in federal prison and 3 percent of women in state prison are pregnant at the time of incarceration.28 For these women, negligent correctional procedures can produce high levels of stress and exacerbate pregnancy-related mental health disorders, which are already disproportionately experienced by black women.29 In 2010, the most recent year for which aggregated data are available, dozens of states did not require medical examinations or prenatal nutrition counseling for pregnant inmates. 30 They also failed to offer pregnant women guidance on recommended activity levels or safety measures during pregnancy.31 Many also failed to comprehensively limit the shackling of pregnant women—including during transportation to the doctor and to the hospital for labor, delivery, and recuperation.32 Banned by the Federal Bureau of Prisons in 2008, this cruel practice increases stress and jeopardizes birth outcomes.33 After giving birth, incarcerated women are frequently rushed back to prison and are unable to breastfeed or otherwise care for and bond with their newborns.34

These traumatic experiences produce mental and physical scars that undermine the long-term health and well-being of women and their infants.35 As discussed above, black women are overrepresented in the criminal justice system and thus at heightened risk of exposure to these unique stressors. This reality contributes to health disparities between African American women and white women.

Indirect contact with the criminal justice system

Indirect contact with the system—such as having an incarcerated loved one—is another traumatic experience that is more likely to affect black women than white women.

For children, having an incarcerated parent is associated with developmental, emotional, and behavioral problems.36 Children with incarcerated parents are also more likely to experience housing instability, homelessness, and health care and nutrition insecurity.37 This trauma lingers well into adulthood and undermines long-term mental health outcomes. One team of researchers discovered that adults who had an incarcerated household member during childhood were at higher risk of poor health-related quality of life.38

Insights from Iowa

Recognizing the role maternal mental health plays in determining birth outcomes, CAP analyzed data drawn from a sample of Iowa residents and found that respondents who had indirect contact with the criminal justice system as children were three times more likely to report experiencing deep depression in the past month—31.2 percent vs. 9.9 percent. They were also more than four times more likely to report feeling nervous most or all the time—14.3 percent vs. 3.8 percent. The relationship between mental health and contact with the system remains significant even after including multiple covariates. (see Methodology)

While indirect contact is associated with worse mental health outcomes regardless of race—and Iowa is not necessarily demographically representative of the country, meaning broad conclusions should not be drawn from one sample—the data do provide insight into a state with some of the starkest racial disparities in incarceration. Black Iowans constitute just 4 percent of the state population but 25 percent of its prison population and are 11 times more likely to be imprisoned than white Iowans. 39 Ultimately, this exposure during childhood puts black Iowans at greater risk of adverse mental health outcomes in adulthood.

While having an incarcerated household member during childhood has severe and long-lasting consequences, having this experience during adulthood also contributes to higher levels of stress. Women typically bear a tremendous emotional and financial burden when a loved one is incarcerated. Beyond significant loss of income, a new CAP analysis found that 45 percent of adults with incarcerated family members supported that person financially during and/or after their sentence.40 Women constitute 83 percent of those responsible for incarcerated family members’ court-related costs and typically pay more than $13,000 in fines and fees alone.41 The financial burden of having an incarcerated loved one means that many families struggle to meet basic food, housing, transportation, and clothing needs.42 In fact more than 1 in 3 affected families—34 percent—go into debt just to pay for phone calls and visits.43

The emotional and financial costs associated with indirect contact undermine the long-term health and well-being of women and children. In fact, half of all people with indirect contact with the system report symptoms of PTSD, hopelessness, or anxiety related to a loved one’s incarceration.44 And because African Americans are overrepresented in the criminal justice system, millions of black women suffer from the stress associated with having a family member incarcerated. This indirect contact with the criminal justice system increases the risk of family instability, unemployment, socioeconomic disadvantage, substance use disorders, and mental health problems.45

Toxic stress from mass incarceration increases the risk of infant mortality for black women

Infants born to black mothers are dying at high rates. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), they are more than twice as likely to die as infants born to white mothers.46 In seeking to explain this disparity, researchers have discovered that protective factors such as education, income, and health care reduce infant mortality rates for many women but do not necessarily reduce the risks for black women.

Achieving postsecondary education, for example, decreases the risk of infant mortality for white women by 20 percent.47 For black women, however, the same accomplishment has no effect on risk of infant mortality.48 And while increasing income in adulthood decreases the risk of infant mortality for white women who experienced childhood poverty by 50 percent,49 the same experience did not have a statistically significant effect for black women.50 The National Institutes of Health recommend early and regular prenatal care to improve chances of a healthy pregnancy.51 But black women who receive early and regular prenatal care are still at greater risk of infant mortality than white women who receive no prenatal care.52 While well-known protective factors may help some women, the evidence is clear—a different type of intervention is needed to help black women and their infants.

An emerging body of research suggests that cumulative stress from enduring a lifetime of structural racism is undermining black women’s health and creating disparities in infant and maternal mortality. Efforts to measure the physiological effects of long-term stress have found that black women are twice as likely as their white counterparts to exhibit high levels of stress.53 The “weathering hypothesis” offers insight into the high levels of stress black women experience. This hypothesis and subsequent research suggest that enduring racism over a lifetime increases stress and ultimately undermines the health of black mothers and their infants.54 A previous CAP analysis found that black women are five times more likely than white women to report adverse physical and emotional symptoms because of recent race-based societal discrimination.55

But interpersonal racism is not the only source of the heightened stress levels among black women. Racist public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms perpetuate racial inequity and expose black people to significant stressors.56 Created and maintained by racist policies and practices, the criminal justice system exposes millions of black women to high levels of stress during their lifetimes. Black women are far more likely to be imprisoned than their white counterparts; they are also far more likely to have an imprisoned family member.57 As discussed above, direct contact with the system increases the risk of sexual violence and infectious illness, loss of connection with family and friends, and trauma from cruel prison policies and practices. Indirect contact can cause emotional distress, loss of income and property, and residential instability. These stressors ultimately harm women’s health and undermine birth outcomes—especially for black women.58

Existing research confirms this relationship. Incarceration is associated with higher odds of low birth weight, preterm birth, and infant mortality.59 Mass incarceration has exposed millions of black women to dangerous stressors that threaten their health and the lives of their offspring. Lawmakers must act to put an end to this persistent form of structural racism.

Conclusion

The United States holds the worst record for infant mortality in the developed world and broad, universal approaches are unlikely to succeed in addressing this persistent problem. Instead, lawmakers should approach this problem using the “targeted universalism” equity framework.60 Developed at the Haas Institute at the University of California, Berkeley, this framework focuses on applying targeted interventions to meet universal goals. To achieve the universal goal of a lower U.S. infant mortality rate, lawmakers must target policies and resources toward specifically addressing black infant mortality. As perhaps the United States’ clearest manifestation of structural racism, the criminal justice system is an important place to start.

Methodology: Data sources and limitations

To determine familial connectedness to the criminal justice system, the authors utilized two data sources. The first was the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). For this analysis, the authors constrained the sample to U.S. residents who answered questions in the Adverse Childhood Experiences module between 2011 and 2013—a sample size of 81,280. The authors then used this module to create several models studying the relationship between race, familial incarceration during childhood, and mental health in adulthood. In studying this relationship, the authors controlled for income level during adulthood, geography, and ten other CDC-designated adverse childhood experiences. The authors included covariates for educational attainment, as well as behaviors such as smoking and drinking heavily, in the analysis of mental health outcomes in adulthood.

The second data set analyzed was based on the AP-NORC Center’s 2017 Phasing Into Retirement survey of Americans over age 50—which has a sample size of 1,683. The authors used this data set to study the relationship between race and the likelihood of familial incarceration during an individual’s lifetime. In studying this relationship, the authors controlled for income level during adulthood and educational attainment. The authors also used this data set to explore financial support of family members who experience incarceration.

The authors made several assumptions when analyzing the BRFSS and AP-NORC data. First, they interpreted a “yes” response to the following BRFSS question as reporting that an immediate family member was incarcerated during the respondent’s childhood: “Looking back before you were 18 years of age … Did you live with anyone who served time or was sentenced to serve time in a prison, jail, or other correctional facility?” The author recognizes that not all individuals live with immediate family members during childhood and accepts this as a limitation of the analysis.

Second, in reporting cross-generational summary statistics, the author relied on cutoff points from the Pew Research Center. Pew defines Baby Boomers as those born between 1946 and 1964, Millennials as those born between 1981 and 1996, and post-Millennials as those born after 1996.61 It must be noted that the BRFSS data utilized for this analysis are limited to individuals born in 1995 or earlier. It is possible that the likelihood of having an incarcerated family member during childhood is very slightly overestimated as incarceration rates declined by 2.7 percent between 2011 and 2013—when those born in 1995 and 1996 were still minors. Similarly, the AP-NORC data utilized for the analysis are limited to those born in 1967 or earlier. It is possible that the likelihood of lifetime familial incarceration for Baby Boomers is slightly underestimated as individuals born between 1965 and 1967 have experienced slightly lower lifetime incarceration rates than individuals born in 1964 or earlier, due to a temporary decline in incarceration rates between 1964 and 1975.62

The primary limitation of this study is the availability and reliability of the data collected for analysis. First, the CDC’s BRFSS only contains data on Adverse Childhood Experiences for 9 states—Iowa, Minnesota, Montana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin. These states are geographically and demographically diverse and produce a sample size of 81,280. Still, readers should use caution when drawing national conclusions due to the possibility that including additional states would have a statistically significant effect on the analysis.

This analysis is also limited by the lack of BRFSS data on inflation adjusted household income during childhood. This is important because the primary variable being tested is familial incarceration during childhood. It is possible that including a covariate for childhood income would have a significant effect on the relationship between race and the likelihood of experiencing a childhood familial incarceration (CFI). Further, childhood income could affect the relationship between experiencing a CFI and reporting higher rates of nervousness and deep depression in adulthood. The authors justify the use of an adult household income variable as a control due to the close correlation between childhood and adult household income.

Finally, omitted variables bias warrants caution here. BRFSS data do not contain data on the specific charges levied against the incarcerated family member, such as domestic violence. A relationship exists between CFI and adverse mental health outcomes even after controlling for abuse, substance use disorder, and other adverse childhood experiences. Still, it is possible that the underlying crime that led to the familial incarceration could be the true source of adverse mental health outcomes for some individuals in the BRFSS.

Connor Maxwell is the research associate for the Progress 2050 team at the Center for American Progress. Danyelle Solomon is the senior director for the Progress 2050 team at the Center.